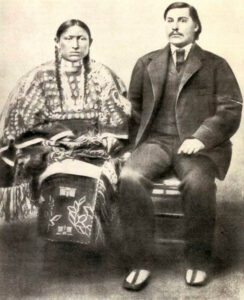

George Bent was a Cheyenne-American interpreter, historian, Civil War soldier, and Cheyenne Dog Soldier who lived in Colorado.

Bent, named Ho-my-ike in Cheyenne, was born on July 7, 1843, to William Bent and his Cheyenne wife, Owl Woman, at Bent’s Fort, Colorado. His father, William Bent, was a famous fur trader from St. Louis, Missouri, who, along with his brother Charles, and partner Ceran St. Vrain, built Bent’s Fort, one of the busiest trading posts in the West. Bent’s Fort was America’s most influential trading post in the 1830s and 1840s. Its trade empire stretched from the fort on the Arkansas River south into the Staked Plains (“Llano Estacado”) of Texas and north into Wyoming’s Medicine Bow Mountains. Many great names of the fur trade were employed by William Bent at one time or another, including Kit Carson, Jim Beckwourth, Old Bill Williams, Uncle Dick Wootton, Thomas Fitzpatrick, and Jim Bridger.

George’s mother, Owl Woman, was the daughter of a respected Cheyenne Chief and medicine man, and her husband, William, became an honorary chief of the tribe after their marriage. William and Owl Woman had four children — Mary was born in 1838, Robert in 1840, George in 1843, and Julia in 1846. When Owl Woman died giving birth to Julia, William took Owl Woman’s two younger sisters as secondary wives in the Cheyenne traditional way of successful men. The youngest sister, Island, essentially reared Owl Woman’s four children. The other sister, Yellow Woman had a son by William Bent named Charles, a half-brother to the others, who was born in 1845.

George Bent was raised according to Cheyenne customs and went by his Cheyenne name Ho—my-ike, meaning Beaver, until he was ten years old. Growing up among various ethnicities at Bent’s Fort, George learned to speak several languages fluently, including English, Cheyenne, French, Spanish, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Comanche.

In 1853, George and his siblings were sent to an Episcopal boarding school in Westport, Missouri, that taught Native American children alongside white children. Entrusting their care to Colonel Albert G. Boone, grandson of Daniel Boone and William’s friend and trade associate, William wanted his children to have an education similar to other wealthy Americans. Though George became friends with many young people from affluent Southern families, he never really felt like he belonged to white American society.

In 1857, after completing his primary education, George was sent to St. Louis, Missouri, and placed in the care of Robert Campbell, a fur trader, and businessman. Campbell was known for freeing his slaves and taking numerous children of color under his wing. Under Campbell’s care, George would begin attending Webster College.

When the Civil War began in 1861, George was 17 years old. In May 1861, Union troops marched Confederate prisoners through the streets of St. Louis when shots were fired. The Union soldiers began firing into the crowd, killing many, and the city was outraged. George and most of his friends at Webster College witnessed this and decided to join the Confederate army. Bent served in the Missouri State Guard fighting at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek near Springfield, Missouri, on August 10, 1861, and at the First Battle of Lexington near Lexington, Missouri, on September 20, 1861, both of which were Confederate victories. As a member of the 1st Missouri Cavalry Regiment, he fought at the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas, March 6–8, 1862, a Union victory. When the Missouri cavalry was converted to infantry, Bent became attached to Landis’ Battery, Missouri Light Artillery, which was part of General Sterling Price’s division. His artillery unit participated in the siege and retreat from Corinth, Mississippi, where it stayed behind to cover the retreat of 66,000 Confederates under the command of P.G.T. Beauregard.

On August 30, 1862, Bent was captured with 200 other rebels near Memphis, Tennessee. He was required to swear an oath of allegiance to the Union and was sent to Gratiot Street Military Prison in St. Louis. However, he spent only two days in the camp when his guardian, Robert Campbell, was able to get George released into the care of his brother, Robert Bent. The two brothers rode together back to their home in Colorado.

Chief Black Kettle

After spending nearly a decade away, George returned to his father’s ranch in Colorado, but the anti-Confederate sentiment was intense. He then became a member of Chief Black Kettle’s Cheyenne tribe in Colorado. There, he lived with his brother Charlie and Charlie’s mother, Yellow Woman.

For many years, the Natives and white settlers had battled over land in the area, and Black Kettle wanted to end the fighting. He gathered members of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes to negotiate peace with the United States. George’s father, William Bent, an honorary Cheyenne chief, was an important part of these peace talks.

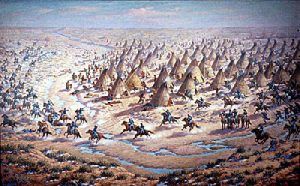

George was at Black Kettle’s camp of Cheyenne and Arapaho at Sand Creek, about 35 miles north of Lamar, Colorado, on November 29, 1864. The Indians in the camp had initiated peace negotiations with the U.S. Army and believed they were under its protection.

However, Colonel John Chivington and his force of 700 Colorado volunteers attacked the village. The soldiers killed about 150 Indians, most of which were old men, women, and children, and very few were armed. Bent’s brother Charles was nearly killed but was rescued by friends, and Jack Smith, another young mixed-race Cheyenne man, was killed in the attack. The soldiers had forced George’s brother Robert to lead them to the camp.

George Bent was among the Indians who fled upstream and found shelter in sandpits dug in the creek bed beneath a high bank. Wounded in the hip, he was with about 100 survivors who crossed the plains to the Indian camps on the Smoky Hill River. He was found there by a friend who returned him to his father’s ranch, where he recovered.

George Bent became very angry after this betrayal by the United States. He renounced his ties to the U.S. and identified only with the Cheyenne tribe.

Immediately, the Cheyenne and Arapaho planned revenge for the Sand Creek Massacre, and the Bent brothers and Charles’ mother, Yellow Woman, joined the Dog Soldiers band. This group was the main force of Native American resistance against the United States. They burned white villages and cut off trading routes to and from Denver in the following months. Though George was never a great fighter, he participated in many Dog Soldier raids.

In January 1865, the young men rode with an Indian army of 1,000 warriors in a successful attack on Julesburg, Colorado, in which they killed many townspeople and soldiers. Afterward, many of the Cheyenne went north to join Lakota Chief Red Cloud on the Powder River in Wyoming. Before leaving the area, they burned many South Platte River Valley homesteads.

Throughout 1865, George Bent fought with Cheyenne, participating in the Battle of Mud Springs and the Battle of Rush Creek, near present-day Broadwater, Nebraska; the Battle of Platte Bridge Station/Red Buttes on July 26, 1865, near present-day Casper, Wyoming, and the three-day Battle of Bone Pile Creek in August, near present-day Wright, Wyoming.

In the summer, the U.S. Army sent the Powder River Expedition, under Brigadier General Patrick E. Connor, into the Powder River Country to punish the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, with orders to kill all men and boys over the age of 12. On September 8, 1865, the Bents were camped with the Cheyenne at the Big and Little Powder Rivers’ confluence near present-day Broadus, Montana, when soldiers were sighted only a few miles away. The troops were the Eastern and Central columns of the Powder River Expedition under Colonel Nelson D. Cole and Brevet Brigadier General Samuel Walker, respectively. The Cheyenne, led by Roman Nose, attacked the moving column to protect their village in what would later be called the Battle of Dry Creek, possibly preventing another Sand Creek Massacre.

Bent participated in 27 Cheyenne war parties but never gave many details about his role in the Indian wars. Many Dog Soldiers, including George’s brother Charles, were killed in 1869 at the Battle of Summit Springs in Colorado.

Afterward, George agreed to act as an interpreter between the United States and the remaining Dog Soldiers, hoping that talking would bring peace between the two groups. The Americans were so impressed by George that they offered him a job as an interpreter for the Indian Agent in charge of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. Bent worked for the newly created Indian Agency headed by Brinton Darlington, the first U.S. Indian Agent for the Cheyenne and Arapaho. In 1870, the Agency was located in El Reno, Oklahoma. Bent lived on the Cheyenne and Arapaho reservation near Colony and worked as a U.S. government employee for most of the rest of his life.

Because of his knowledge of both European-American and Cheyenne cultures, Bent became a prominent and influential person on the reservation. During the first several years, he tried to moderate hostilities between the two cultures.

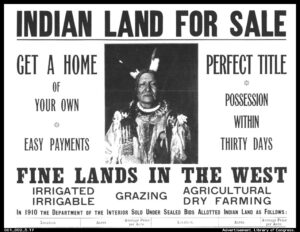

During this time, he developed a serious problem with alcohol. However, he became prosperous by assisting cattlemen in obtaining grazing leases on Indian land. Because of his influence peddling, he lost the trust of some Cheyenne leaders and was fired as a U.S. interpreter. But in 1890, he was the crucial go-between to persuade the Cheyenne and Arapaho to accept plans for allotment of land by individual households under the Dawes Act. Presented as a way for Indians to assimilate by adopting Euro-American farming styles, the allotment plan caused the loss of considerable tribal land. The former communal tribal land was allocated to members’ households, and any remaining land was declared “surplus” by the government, making it available for sale to non-Indian parties. Many Cheyenne and Arapaho held Bent responsible for the ill effects of this transition, even though it would have occurred without Bent’s assistance.

By 1901 Bent was at a low stage in his life. Though he had stopped drinking, he had lost his influence with the Cheyenne and his earlier prosperity. He saw that Cheyenne culture was disappearing and wanted to preserve the history of the Cheyenne. He soon met with anthropologist George Bird Grinnell, who realized that Bent, who spoke both Cheyenne and English, would be invaluable for his research into Cheyenne culture. Bent wrote over 400 letters to George Grinnell’s assistant, George Hyde, about Cheyenne history and customs. He also shared what he knew with Grinnel and arranged interviews with other Cheyenne for more information. However, Bent felt like Grinnell was too slow to finish his book and began collaborating with the deaf, nearly blind, and reclusive George E. Hyde. Eventually, at Bent’s recommendation, Hyde became a ghostwriter for Grinnell and probably wrote most of The Fighting Cheyennes, published in 1915.

Later, Grinnell wrote The Cheyenne Indians: Their History and Lifeways, in which he was more generous in crediting Bent. Cheyenne culture is unusually well described in Grinnell’s books, thanks mainly to Bent’s insights and Hyde’s writing.

George Bent died on May 19, 1918, in Washita, Oklahoma, during the 1918 flu pandemic.

During his life, George was married three times. The first was to Magpie, one of Black Kettle’s nieces. His other wives were Kiowa Woman and Standing Out. With them, Bent had a total of six children.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2022.

Also See:

Indian Wars, Battles & Massacres

Indian Wars of the Frontier West

Sources: