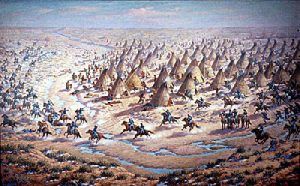

After the Sand Creek Massacre of the Cheyenne and Arapaho on November 29, 1864, a number of Colorado and Kansas tribes began to intensify hostilities against the U.S. Army and White settlers. During the massacre, as many as 150 Indians, most of which were old men, women, and children, were killed.

Afterward, many of the Cheyenne survivors fled north to the Republican River, where the main body of their tribe, including a large contingent of “Dog Soldiers,” were camped.

They soon sent a messenger to the Sioux and Arapaho inviting them to join them in a war on the whites. On January 1, 1865, the tribes met on Cherry Creek, near present-day St. Francis, Kansas, to plan revenge. In the meeting were the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers, the Northern Arapaho, and two bands of Lakota Sioux, including the Brule, under Chief Spotted Tail, and the Oglala, under war leader Pawnee Killer.

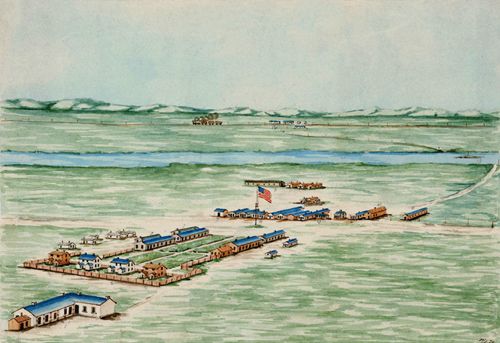

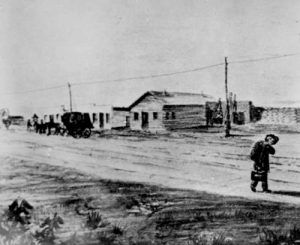

In early January 1865, as many as 2000 Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho warriors shifted their camps closer to the South Platte River, where it cut through the northeast corner of Colorado. In the midst of this area stood the rough and tumble town of Julesburg, which was home to the Overland Trail stagecoach station and the site of Fort Rankin (later Fort Sedgwick).

On January 6, 1865, a small party of Indians hit a wagon train and killed 12 men.

In the early morning hours of January 7th, the Indians attacked Fort Rankin. While the majority of the Indians concealed themselves in some sandhills a short distance from the fort, Cheyenne Chief Big Crow and about ten of his warriors charged the fort and then quickly retreated. In response, Captain Nicholas O’Brien led a 60-man cavalry troop out of the fort to chase the would-be attackers.

Little did the soldiers know that about three miles from the fort, up to 1000 warriors were hidden in the nearby bluffs. Lucky for O’Brien and most of his men, some young Indian warriors fired prematurely, alerting him of the large group waiting. Turning tail, the troops fled back to the fort with the Indians in pursuit, cutting off some of the soldiers before they reached the safety of the fort. Of those who hadn’t reached the fort, they dismounted to defend themselves. In the battle, 14 soldiers and four civilians were killed. Captain O’Brien and the rest of his men made it back to shelter in the fort.

As the remaining troops prepared to defend the fort against further attack, the Indians raced up the Platte River to the undefended settlement of Julesburg, where they looted the stage station, store, and warehouse, carrying away a large amount of plunder. Within three days, the warriors had returned to their camp at Cherry Creek, Kansas where they distributed the desperately needed goods. The encampment was soon a scene of great feasting and dancing.

In response to the attack on Fort Rankin, General Robert Byington Mitchell gathered 640 cavalry, a battery of howitzers, and some 200 supply wagons at Cottonwood Springs, which was located near present-day North Platte, Nebraska. He then marched southwest to find and punish the Indians who had attacked Julesburg. On January 19th, he found their camp on Cherry Creek, but the Indians had departed several days previously. The weather was bitterly cold, and with more than 50 of his soldiers incapacitated by frostbite, Byington gave up the chase and returned to his base.

In the meantime, the Indians raided ranches and stagecoach stations up and down the South Platte River Valley. The Sioux struck east of Julesburg, the Cheyenne west of Julesburg, and the Arapaho in between. George Bent, the mixed-race son of William Bent, the founder of Bent’s Fort, and his Cheyenne wife was with this group of Indians. He would later say that at night “the whole valley was lighted up with the flames of burning ranches and stage stations, but the places were soon all destroyed, and darkness fell on the valley.”

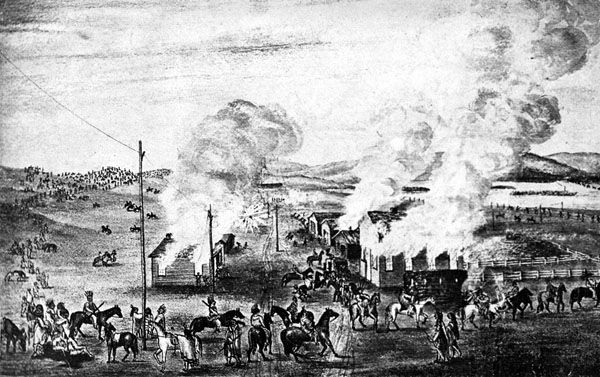

Just weeks after the first attack at Julesburg, the warriors returned in force on February 2nd, where they once again looted the town and, this time, burned it to the ground. They also looted some wagon trains that had sought refuge there. The 15 soldiers and 50 civilians sheltered at nearby Fort Rankin did not venture outside the fort’s walls. As the fire and smoke poured from the settlement, Captain O’Brien and 14 of his men, who had been away from the fort, returned to Julesburg. O’Brien scattered the Indians with a round from his field howitzer, and the Indians fled.

Meanwhile, a caravan of several thousand Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, that included women and children were traveling north to the Black Hills and Powder River Country of South Dakota and Wyoming.

Along the way, their warriors would have additional skirmishes with the army at Mud Springs, near present-day Dalton, Nebraska, and Rush Creek, near Broadwater, Nebraska.

The war with the whites would last for more than another ten years, culminating in the Battle of the Little Big Horn in Montana in 1876.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, September 2022.

Also See:

Indian Wars, Battles & Massacres

Julesburg, Colorado – Wicked in the West

Sources:

Fort Tours

Kansas Travel

Wikipedia

Reporter Herald