“A fear and panic of influenza, akin to the terror of the Middle Ages regarding the Black Plague, [has] been prevalent in many parts of the country.”

— American National Red Cross, 1920

The 1918 influenza pandemic was the deadliest in recent history. Sometimes referred to as the Spanish Flu, it was an unusually deadly influenza strain caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin.

Although there is no universal consensus regarding where the virus originated, it spread worldwide, infecting 500 million people or about one-third of the world’s population. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide, with about 675,000 occurring in the United States.

Influenza, or flu, is a virus that attacks the respiratory system and is highly contagious. When an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks, respiratory droplets are transmitted into the air and can then be inhaled by anyone nearby. Additionally, someone who touches something with the virus and then touches their mouth, eyes, or nose can become infected.

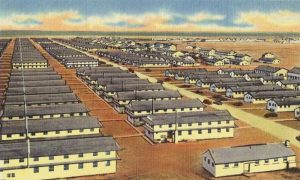

The most likely sites of origin are thought to have been either the United States or France. On March 11, 1918, one of the first to be diagnosed was an Army private at Fort Riley, Kansas, who reported to the base hospital with flu-like symptoms early in the morning. Before the day was over, some 100 soldiers had similar symptoms, and that spring, 48 soldiers died of pneumonia.

“As the early outbreak at Fort Riley suggested, the primary breeding ground for influenza consisted of army camps that were springing up all over America in the early days of 1918. America had entered World War I the previous October, and many young men were anxious to do their part and join the fight. As a result, the camps soon became overcrowded with recruits and service veterans brought in from all over the country to train them.”

— Charles River Editors, The 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic, 2014

When the 1918 flu hit, doctors and scientists were unsure what caused it or how to treat it. Unlike today, no effective vaccines, antivirals, or drugs treat the flu.

Amid World War I, the flu quickly spread across the country, where 2 million troops were mobilizing for the war in Europe. Many of these soldiers were sent to Europe, where the flu spread, mutated, and became more deadly. Before long, it also spread to Asia and, within months, to almost every other part of the world.

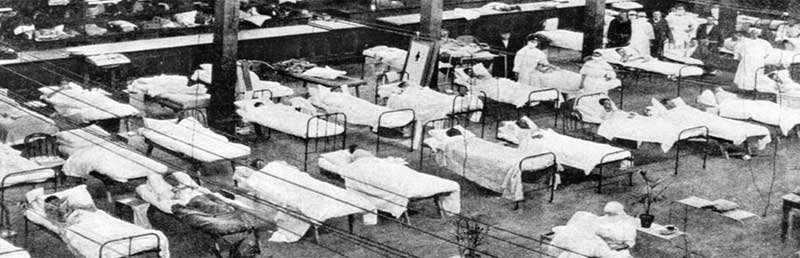

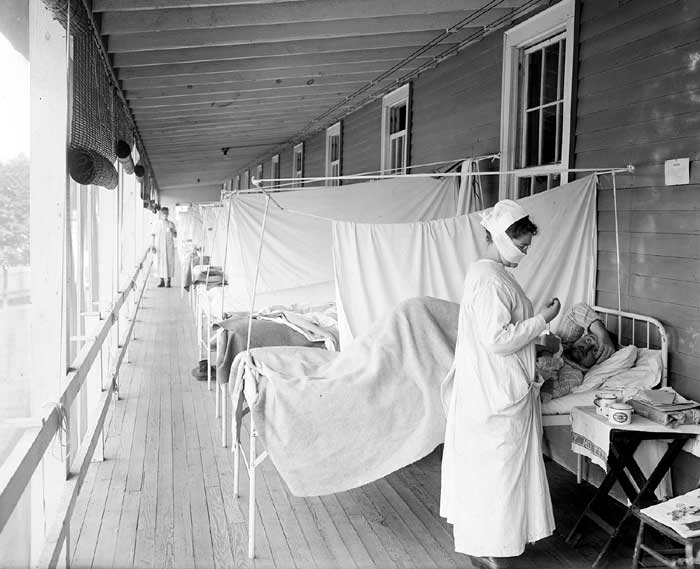

Influenza Ward, Walter Reed Hospital, Washington, D.C.

Unlike the seasonal flu, pandemic flu is one for which there is little or no human immunity. This strain, initially called “the three-day fever,” started like any flu, with a cough, headache, and fatigue followed by intense chills and high fever. However, as more people contracted the disease over time, the symptoms worsened and lasted up to a month before survivors felt entirely well.

Initially, the flu set off a few alarms because, in the beginning, it rarely killed despite the enormous number of people infected. For example, doctors in the British Grand Fleet admitted 10,313 sailors to sickbay in May and June, but only four died. It only got great attention when it swept through Spain and sickened the king, garnering headlines in Spanish newspapers. After this, the disease became known as the “Spanish Flu.”

“King George’s Grand Fleet could not even put to sea for three weeks in May, with 10,313 men sick.”

— Gina Kolata, Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918, 2011

Influenza reached from Algeria to New Zealand by June but was relatively mild, with few deaths. However, almost half who did die were healthy young adults, who generally have the strongest immune systems. In these cases, their immune systems essentially overreacted, destroying their lungs to get to the virus.

By July, a U.S. Army medical bulletin reported from France the “epidemic is about at an end… and has been throughout of a benign type.” A British medical journal flatly stated that influenza “has completely disappeared.” By summer, it seemed to have played itself out.

Then, in late August, a second wave began in Camp Devens, an Army training base 35 miles northwest of Boston, Massachusetts. This time, the disease was far more lethal. While some people reportedly dropped dead on the street, others held on for days.

This camp, which had 45,000 soldiers and could accommodate 1,200 patients, held 84 infected people on September 1. These patients appeared with deep brown spots on their cheeks, and thick, bloody fluids overwhelmed their lungs. Their faces were often blue as their blood wasn’t getting oxygenated, and soon, victims started to drown in their own fluid.

“It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes, and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate… It is horrible.”

— A Camp Devens Doctor

On September 7, a soldier arriving at the hospital deliriously and screaming when touched was diagnosed with meningitis. The next day, a dozen more men from his company were also diagnosed with meningitis. But as more and more men fell ill, physicians changed the diagnosis to influenza, reporting “the influenza… occurred as an explosion.”

About 100 people, including doctors and nurses, died each day at Camp Devens during the first week of September.

“It takes special trains to carry away the dead. There were no coffins for several days, and the bodies piled up something fierce; we used to go down to the morgue and look at the boys in long rows. It beats any sight they ever had in France after a battle.”

— A Camp Devens Doctor

At the outbreak’s peak, 1,543 soldiers reported ill with influenza each day, and the hospital was overwhelmed. With too few doctors and nurses and insufficient staff to feed patients and staff, the hospital ceased accepting patients, leaving thousands more sick and dying in barracks. By the end of September, 50,000 people in Massachusetts had been infected with the flu.

At the same time, a Navy ship from Boston carried influenza to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in early September, where the disease erupted in the Navy Yard. The day after the city’s public health director declared that he would “confine this disease to its present limits,” two sailors died. The next day, another 14 sailors and the first civilian passed away. Even though the disease killed more and more people each day, the newspapers assured readers that influenza posed no danger, and the public health director assured the city he would “nip the epidemic in the bud.”

He was wrong — very wrong. By September 26, influenza had spread across the country, and because so many military training camps were in the same shape as Camp Devens, the Army canceled its nationwide draft call.

Meanwhile, a large Liberty Loan parade to raise money for the war was scheduled in Philadelphia for September 28. Doctors urged the city to cancel it and tried to convince the press to write stories about the danger. But the city and newspaper editors refused, and the largest parade in Philadelphia’s history proceeded on schedule.

Two days after the parade, the city conceded that the epidemic “now present in the civilian population was… assuming the type found in Army camps.” However, the spokesman cautioned the public not to be “panic-stricken exaggerated reports.” Ultimately, the city closed all schools, churches, and theaters and banned public gatherings. Before it was over, the epidemic in Philadelphia would kill 12,000 people, nearly all of them in six weeks. It was so bad that one day, 759 people died of influenza — many of whom were buried in mass graves.

Having spread across the country by then, New York reported that the death tally for one day was 851. San Francisco, California, also reported hundreds of cases, as did Chicago, Illinois, where there were so many deaths that the city banned funerals

Amid these many deaths, the government and public health officials aggravated the situation by concealing the truth from the public. Determined to keep up the morale of the people during the war, numerous statements were made that were not true.

The U.S. Surgeon General Rupert Blue said, “There is no cause for alarm if precautions are observed.” Other officials, including New York City’s public health director and the Los Angeles public health chief, followed suit, making similar statements. And the press followed along.

At Camp Pike, Arkansas, 8,000 soldiers were admitted to the base hospital over four days in October. The Gazette newspaper in nearby Little Rock ran the headline “Spanish influenza is plain la grippe—same old fever and chills.”

“Every corridor and there are miles of them with double rows of cots …with influenza patients…There is only death and destruction.”

— Francis Blake, a member of the Camp Pike’s particular pneumonia unit

But the public wasn’t fooled. They could see it with their own eyes. Victims died within hours of the first symptoms — horrific symptoms such as coughing up blood and bleeding from the nose, ears, and eyes. The disease wiped out entire families or left countless widows and orphans. Funeral parlors were overwhelmed, and people were being buried in mass graves. Many dug graves for their family members.

Not able to believe anything that was being told to them by officials or newspapers, people grew fearful, and society began to disintegrate. As trust evaporated and fear increased, they began to look out only for themselves.

In Philadelphia, the head of Emergency Aid pleaded, “All who are free from the care of the sick at home… report as early as possible… on emergency work.” But volunteers did not come. Other agencies around the country made similar pleas to take in children whose parents were dying or dead, volunteer helpers, and food for families, but still few replied.

“We were actually almost afraid to breathe… You were afraid even to go out… The fear was so great people were actually afraid to leave their homes… afraid to talk to one another.”

— Dan Tonkel, Goldsboro, North Carolina Resident

The flu was also detrimental to the economy. Fear and sickness emptied places of employment, and essential services such as mail delivery and garbage collection were hindered due to flu-stricken workers. In the Northeast, shipbuilding workers were told they were as crucial to the war effort as soldiers at the front. However, many companies experienced 40-50% absenteeism. In some places, there weren’t enough farm workers to harvest crops. Complicating matters was that World War I had left parts of America with a shortage of physicians and other health workers. Of those that remained, many came down with the flu themselves, causing state and local health departments to close and hampering efforts to provide the public with answers about it. Hospitals in some areas were so overloaded with flu patients that schools, private homes, and other buildings had to be converted into makeshift hospitals, some of which were staffed by medical students.

“A fear and panic of the influenza, akin to the terror of the Middle Ages regarding the Black Plague, [has] been prevalent in many parts of the country.”

— American Red Cross Report

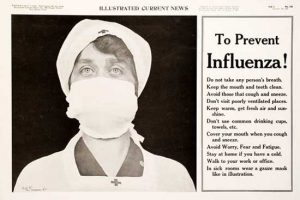

Stores canceled holiday sales to keep crowds down, and shoppers were encouraged to phone in their orders. Though at least one minor league baseball game was played under these circumstances, all the players and everyone in the crowd wore gauze masks. Libraries stopped lending books, and regulations were passed banning spitting.

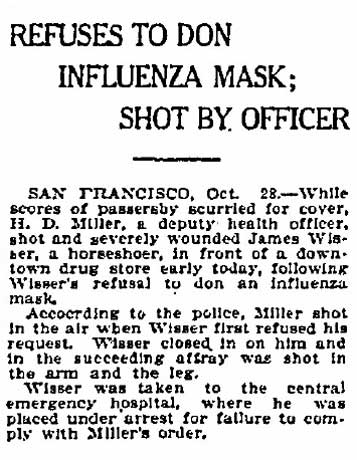

Officials in some communities imposed quarantines, ordered citizens to wear masks, and shut down public places, including schools, churches, and theaters. “Obey the laws, and wear the gauze, protect your jaws from septic paws,” warned one jingle. In one case in San Francisco, an officer shot a man who refused to don a flu mask. Though the man lived, he was arrested after he was treated for failure to obey the officer.

In New York City, the health commissioner tried to slow the transmission of the flu by ordering businesses to open and close on staggered shifts to avoid overcrowding on the subways. In Ogden, Utah, officials sealed off the town, and no one was allowed in or out without a doctor’s note. The governor of Alaska closed the ports and posted U.S. marshals to guard them. But, it would not be enough. In Nome, just south of the Arctic Circle, 176 of 300 Alaska Natives died.

Fear emptied cities and the streets as people stayed indoors and refused to come out.

“If the epidemic continues its mathematical rate of acceleration, civilization could easily disappear… from the face of the earth within a matter of a few more weeks.”

— Victor Vaughan, Former Dean of the University of Michigan’s Medical School

October 1918 was the deadliest month in U.S. history, with 195,000 fatalities from the flu. But it was not yet over as it continued through November when at least 115,000 people in California were stricken ill.

Then, as suddenly as it came, influenza decreased dramatically as infected people died or developed immunity. Though an undercurrent of unease remained, it was aided by the euphoria accompanying the war’s end in November 1918. Finally, traffic returned to streets, schools and businesses reopened, and in the months ahead, society returned to normal.

By the end of 1918, the flu had killed 57,000 American soldiers — 4,000 more people than those killed in combat. More people were infected and died in 1919, but the flu pandemic had completely ended by that summer. During this time, 25% of Americans contracted the virus, and its death toll dropped the average life expectancy in the United States by 12 years.

Although the death toll attributed to the Spanish Flu is often estimated at 20 million to 50 million victims worldwide, other estimates run as high as 100 million victims, or about three percent of the world’s population.

One unusual aspect of the 1918 flu was that it struck down many previously healthy young people — a group normally resistant to this infectious illness.

Almost 90 years later, in 2008, researchers announced they’d discovered what made the 1918 flu so deadly: A group of three genes enabled the virus to weaken a victim’s bronchial tubes and lungs and clear the way for bacterial pneumonia. Malnourishment, overcrowded medical camps and hospitals, and poor hygiene also exacerbated it. The superinfection killed most victims, typically after a somewhat prolonged deathbed.

Since 1918, other pandemic cases of flu have struck the United States. These included the Asian flu of 1957-1958, which killed 70,000 Americans; the Hong Kong flu of 1968-1969, which killed 34,000 Americans; the Swine Flu in 2009-2010, which killed 12,000; and the, as of this update, the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic, which started in late 2019 and has since killed 6.51 million worldwide, including over one million in the United States.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

“It kept people apart…You had no school life, you had no church life, you had nothing… It destroyed all family and community life… The terrifying aspect was when each day dawned, you didn’t know whether you would be there when the sun set that day.”

— William Sardo, Washington, D.C. Resident

Also See:

Sources:

Center for Disease Control

History.com

National Library of Medicine

Popular Mechanics

Smithsonian Magazine

Wikipedia