Shortly after the discovery of America, the Spanish people became obsessed with the idea that somewhere in the interior of the New World, there were rich mines of gold and silver, and various expeditions were sent out to search for these treasures. As every significant event in history is the sequence of something which went before, to gain an intelligent understanding of the expedition of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado in search of the Seven Cities of Cibola and the country of Quivira (1540-42), it is necessary to notice the occurrences of the preceding decade briefly. Pedro de Castaneda, the historian of the expedition, began his narrative as follows:

“In the year 1530, Nuno de Guzman, who was president of New Spain, had in his possession an Indian, one of the natives of the Valley of Otixipar, who was called Tejo by the Spaniards. This Indian said he was the son of a trader who was dead, but that when he was a little boy, his father had gone into the backcountry with fine feathers to trade for ornaments and that when he came back, he brought a large amount of gold and silver, of which there is a good deal in that country. He went with him once or twice and saw some very large villages, which he compared to Mexico and its environs. He had seen seven very large towns which had their streets of silver workers.”

The effect of a story of this nature upon the Spanish mind can be readily imagined. It aroused Guzman’s curiosity, ambition, and greed and influenced all the enterprises he directed along the Pacific Coast to the north. Gathering together a force of 400 Spaniards and several thousand friendly Indians, he started searching for the “Seven Cities.” But before he had covered half the distance, he met with serious obstacles; his men became dissatisfied and insisted on turning back. At about the same time, Guzman received information that his rival, Hernando Cortez, had come from Spain with new titles and powers, so he abandoned the enterprise. Before turning his face homeward, however, he founded the town of Culiacan, from which incursions were made into southern Sonora to capture and enslave the natives.

In 1535 Don Antonio de Mendoza became viceroy of New Spain. The following spring, there arrived in New Spain Cabeça de Vaca, Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, Andres Dorantes, and a black man named Estevanico, survivors of the Narvaez expedition, which had sailed from Spain in June 1527. For six years, these men had been captives among the Indians of the interior, from which they had heard stories of rich copper mines and pearl fisheries. These stories they repeated to Mendoza, who bought the black man to have him guide an expedition to explore the country. Still, it was three years later before a favorable opportunity for his project was offered.

In 1538 Guzman was imprisoned by a Juez de Residencia, who worked for Diego Perez de la Torre, who ruled Culiacan’s province for a short time. When Mendoza appointed his friend, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, governor of New Galicia, situated on the west coast of Mexico, the new province included the old one of Culiacan. Coronado had come to New Spain with Mendoza in 1535. Two years later, he married Beatrice de Estrada, a cousin of Charles V, King of Spain. About the time of his marriage, Mendoza sent him to quell a revolt among the Indians in the mines of Amatapeque, which he did very successfully. Because of his success and probably his family ties, the viceroy appointed him governor of New Galicia.

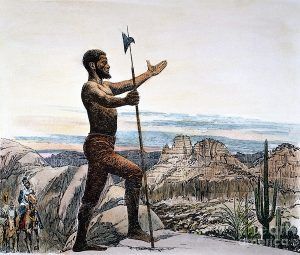

Coronado showed a willingness to assist and encourage Mendoza to find the “Seven Cities,” and on March 7, 1539, what might be termed a reconnoitering party, left Culiacan under the leadership of Friar Marcos de Niza, with Estevanico as the guide. Father Marcos had been a member of Alvarado’s expedition to Peru in 1534. Upon reaching a place called Vapaca in central Sonora, Mexico, Marcos sent Estevanico toward the north “with instructions to proceed 50 or 60 leagues and see if he could find anything which might help them in their search.”

Four days later, Estevanico sent Father Marcos a large cross, and the messenger who brought it told of “seven very large cities in the first province, all under one lord, with large houses of stone and lime; the smallest one story high, with a flat roof above, and others two and three stories high, and the house of the lord four stories high. And on the portals of the principal houses, there are many designs of turquoise stones, of which he says they have a great abundance.”

A little later, Estevanico sent another cross by a messenger who gave a more specific account of the seven cities. Father Marcos determined to visit Cibola to verify the messengers’ statements. He left Vapaca on April 8, expecting to meet Estevan at the village from which the second cross was sent, but upon arriving there, he learned that the black man had gone northward toward Cibola, which was a 30 days journey. The friar continued on his way until he met an inhabitant of Cibola, who informed him that Estevan had been put to death by the Cibolan chiefs. Marcos obtained a view of the city from the top of a hill, after which he hastened back to Compostela and reported his investigations to Governor Coronado.

The immediate effect of his report, in which he stated that the city he saw from the top of the hill was “larger than the city of Mexico,” was to awaken the people of New Spain’s curiosity and create a desire to visit the newly discovered region. In response to this sentiment, Mendoza ordered a force to assemble at Compostela, ready to march to Cibola in the spring of 1540. Arms, horses, and supplies were collected, and the greater part of the winter was spent preparing. In casting about for a leader, the viceroy’s choice fell on Governor Francisco Vasquez de Coronado.

In addition to the 300 Spaniards, there were 800 to 1,000 Indians. Of the Spaniards, about 260 rode horses, while 60 marched along with some 1,000 Indians. They were equipped with six swivel guns, more than 1,000 spare horses, and many sheep and swine.

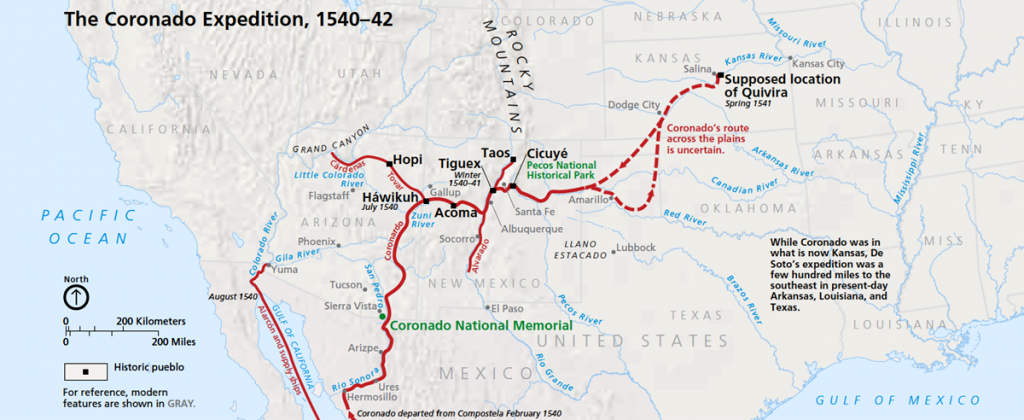

On February 23, 1540, Coronado left Compostela with his army and reached Culiacan in late March. Here, the expedition rested until April 22, when the real march to the “Seven Cities” began. Coronado followed the coast, bearing off to the left,” and entered the White Mountain Apache country of Arizona in June. Mendoza, believing the expedition’s destination to be somewhere near the coast, sent from Natividad two ships, under Pedro d’Alarcon, to take to Xalisco all the soldiers and supplies the command could not carry.

As the expedition advanced, detachments were sent out in various directions to explore the country. In June, Coronado reached the valley of the Corazones — so named by Cabeça de Vaca because the natives there offered him the hearts of animals for food. Here, the army built the town of San Hieronimo de los Corazones (St. Jerome of the Hearts) and then moved on toward Cibola. There has been considerable speculation about the location of the fabled “Seven Cities,” but it was thought to have been the site of the Zuni pueblos in the western part of New Mexico.

On July 7, 1540, Coronado captured the first city, the Pueblo of Hawikuh, which he named Granada. After capturing this place, the Indians retired to their stronghold on Thunder Mountain. Coronado reconnoitered and, on August 3, dispatched Juan Gallego with a letter to Mendoza, advising him of the progress and achievements of the expedition.

The army went into winter quarters at Tiguex, near the present city of Albuquerque, New Mexico. During the winter, the army subjugated the hostile natives in the pueblos of the Rio Grande. While at Tiguex, Coronado heard from one of the Plains Indians, a slave in the village of Cicuye, the stories about Quivira. This Indian, whom the Spaniards called “The Turk,” told them his masters had instructed him to lead them to certain barren plains, where water and food could not be obtained, and leave them there to perish, or, if they succeeded in finding their way back they would be so weakened as to fall an easy prey.

George Parker Winship, in his 1896 book, The Coronado Expedition, said:

“The Turk may have accompanied Alvarado on the first visit to the great plains, and he doubtless told the white men about his distant home and the roving life on the prairies. It was later, when the Spaniards began to question him about nations and rulers, gold and treasures, that he received, perhaps from the Spaniards themselves, the hints which led him to tell them what they were rejoiced to hear and to develop the fanciful pictures which appealed so forcibly to all the desires of his hearers. The Turk, we cannot doubt, told the Spaniards many things which were not true. But in trying to trace these early dealings of the Europeans with the American aborigines, we must never forget how much may be explained by the possibilities of misrepresentation on the part of the white men, who so often heard of what they wished to find, and who learned, very gradually and in the end very imperfectly, to understand only a few of their native languages and dialects… Much of what the Turk said was very likely true the first time he said it, although the memories of home were heightened, no doubt, by absence and distance. Moreover, Castaneda, who is the chief source for the stories of gold and lordly kings which are said to have been told by the Turk, in all probability did not know anything more than the reports of what the Turk was telling the superior officers, which were passed about among the common foot soldiers. The present narrative (Castenada’s) has already shown the wonderful power of gossip, and when it is gossip recorded twenty years afterward, we may properly be cautious in believing it.”

Whatever the nature of the Turk’s stories, they influenced Coronado to undertake an expedition to the province of Quivira. On April 10, 1541, he wrote from Tigeux to the king. That letter has been lost, but it no doubt contained a review of the information he had received concerning Quivira and an announcement of his determination to visit the province. The trusted messenger, Juan Gallego, was sent back to the Corazones for reinforcements but found San Hieronomo almost deserted. He then hastened to Mexico, where he raised a small body of recruits, with which he met Coronado as the latter was returning from Quivira.

On April 23, 1541, guided by the Turk, Coronado left Tiguex, taking every member of his army who was present. The march was first to Sicuye (the Pecos Pueblo), a fortified village five days distant from Tiguex. From this point, the route followed by the expedition has been the subject of considerable discussion.

General J.H. Simpson, who devoted much time and study to the Spanish explorations of the southwest, prepared a map of the Coronado Expedition, showing that he crossed the Canadian River near the boundary between the present counties of Mora and San Miguel in New Mexico, then north to a point about half-way between the Arkansas and Canadian Rivers, and almost to the present line dividing Colorado and New Mexico. The course changed to the northeast and continued in that general direction to a tributary of the Arkansas River, about 50 miles west of Wichita, Kansas.

In his 1893 book, Gilded Man, A.F.A. Bandelier said the general direction from Cicuye was northeast and that “on the fourth day, he crossed a river that was so deep that they had to throw a bridge across it. This was perhaps the Rio de Mora and not, as I formerly thought, the Little Gallinas River, which flows by Las Vegas, New Mexico. But it was probably the Canadian River, into which the Mora River empties.” The same writer, in his reports of the Hemenway Archaeological Expedition, said that after crossing the river, Coronado moved northeast for 20 days when they changed course to almost east until he reached a stream “which flowed in the bottom of a broad and deep ravine, where the army divided, Coronado, with 30 picked horsemen, going north and the remainder of the force returning to Mexico.

Frederick W. Hodge’s map, in his 1907 book, Spanish Explorations in the Southern United States, shows the course of the expedition to be southeast from Cicuye to the crossing of the Canadian River, then east and southeast to the headwaters of the Colorado River in Texas, where the division of the army took place.

George Parker Winship, in his 1896 book, The Coronado Expedition, goes a little more into detail than any of the other writers, saying: “The two texts of the Relacion del Suceso differ on a vital point; but despite this fact, I am inclined to accept the evidence of this anonymous document as the most reliable testimony concerning the direction of the army’s march. According to this, the Spaniards traveled east across the plains for 100 leagues (265 miles) and 50 leagues either south or southeast. The latter is the reading I should adopt because it accommodates the other details somewhat better. This took them to the point of separation, which can hardly have been south of the Red River, and was much more likely somewhere along the north fork of the Canadian River, not far above its junction with the mainstream.”

When the army divided in May, Coronado reckoned that he was 250 leagues from Tiguex. The separation was the food scarcity for the men and the weakened condition of many horses, which could not continue the march. During the march to this point, a native insisted that the Turk was lying, and the Indians they met failed to corroborate the Turk’s account.

Coronado’s suspicions were finally aroused. He sent for the Turk, questioned him closely, and made him confess that he had been untruthful. The Indian still maintained, however, that Quivira existed, though not as he had described it. From the time the army divided, all accounts agree that Coronado and his 30 selected men went north to a large stream. They crossed and descended in a northeasterly direction for some distance and then, continuing their course, soon came to the southern border of Quivira.

George Parker Winship said that the army returned due west to the Pecos River “while Coronado rode north ‘by the needle.’ From these premises, which are broad enough to be safe, I should be inclined to doubt if Coronado went much beyond the southern branch of the Kansas River, even if he reached that stream.”

The “large stream” mentioned in the relations is believed to have been the Arkansas River. The expedition crossed near present-day Dodge City, Kansas, then followed down the left bank to Great Bend’s vicinity, where the river changes its course. At the same time, Coronado proceeded almost straight to the neighborhood of Junction City. At the limit of his journey, he set up a cross bearing the inscription: “Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, commander of an expedition, arrived at this place.”

Toward the latter part of August, Coronado left Quivira and started on his return trip. On October 20, he was back in Tiguex, writing his report to the king. The army wintered again at Tiguex and started for New Spain in the spring of 1542, where they arrived the following fall. His report to the viceroy was coldly received, which seems to have piqued the gallant captain-general. Soon afterward, he resigned as governor of New Galicia and retired to his estate. His expedition was a failure, so far as finding gold and silver was concerned, but the failure was not the commander’s fault. On the other hand, the Spaniards gained accurate geographical information- at least for that day- of a large section of the continent’s interior.

Four priests started with the expedition, including Father Marcos, who had previously been sent out to find the seven cities of Cibola, Juan de Padilla, Luis de Ubeda, and Juan de la Cruz. Father Marcos returned to Mexico with Juan Gallego in August 1541 and was not again mentioned in connection with the expedition. The other three friars remained as missionaries among the Indians, who killed them. Father Padilla was killed in Quivira, Father Cruz at Tiguex, and Father Ubeda at Cicuye.

Following Castaneda and Jaramillo’s narratives and the Relacion del Suceso, it is comparatively easy to distinguish specific landmarks that seem to establish conclusively the fact that the terminus of Coronado’s Expedition was somewhere in central or northeastern Kansas. The first of these landmarks is the crossing of the Arkansas River, near where the Santa Fe Trail crossing was afterward established. The second is the three-day march along the north bank of that stream to where the river changes its course.

The next is the southwest border of Quivira, where Coronado first saw the hills along the Smoky Hill River. Another is the ravines mentioned by Castaneda as forming the eastern boundary of Quivira, which corresponds to the country’s surface about Fort Riley and Junction City. In addition to these landmarks, several relics of Spanish origin in southwestern Kansas have been found. Professor J. A. Udden of Bethany College found a Spanish chain mail fragment in a mound near Lindsborg, Kansas. W.F. Richey of Harveyville, Kansas, presented to the State Historical Society a sword found in Finney County bearing a Spanish motto and Juan Gallego’s name near the hilt. Richey also reported finding another sword in Greeley County — a two-edged sword of the style of the Spanish dagger of the 16th century. And, near Lindsborg, the iron portion of a Spanish bridle and a bar of lead was marked with a Spanish brand. In light of all this circumstantial evidence, it is almost certain that Coronado’s expedition terminated somewhere near the Smoky Hill and Republican Rivers’ junction.

One sad feature of the expedition was the Turk’s fate, whom Coronado put to death upon finding that the Indian had misled him. However, the poor native’s state of mind had no doubt been encouraged, if not inspired, by the Spanish soldiers’ covetousness.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, January 2023.

About the Article: The majority of this historic text was published in Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Volume I; edited by Frank W. Blackmar, A.M. Ph. D.; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912. However, the text that appears on these pages is not verbatim, as additions, updates, and editing has occurred.

Also See:

Francisco Vazquez de Coronado – Exploring the Southwest