One of the nation’s oldest national parks, Grand Canyon National Park’s great chasm, carved over millions of years, is one of the world’s major natural wonders. With its awe-inspiring views, turbulent Colorado River, numerous hiking trails, and diverse recreational opportunities, the park attracts more than 5 million visitors annually.

An extensive system of tributary canyons, the National Park covers more than 1,900 square miles. The canyon is 217 miles long, 1 mile deep, and 4-18 miles wide.

The history of people within the canyon dates back 10,500 years, to the earliest documented evidence of human presence in the area. Native Americans have lived at or near the Grand Canyon for at least 4,000 years, with the earliest known inhabitants being the Anasazi.

Grand Canyon, Arizona. Standing Grand and beautiful as seen from the South Rim. Photo by David Fisk.

These ancient Indians inhabited the rim and the inner canyon, surviving by hunting, gathering, and limited agriculture. Later, the Cohonina tribe lived west of the current site of Grand Canyon Village. However, by the late 13th century, both tribes had moved on, most likely due to drought.

For approximately 100 years, the canyon area remained uninhabited. The Paiute from the east and the Cerbat from the west were the first humans to reestablish settlements in and around the Grand Canyon. The Paiute settled the plateaus north of the Colorado River, and the Cerbat built their communities south of the river, on the Coconino Plateau. Sometime in the 15th century, the Navajo, also known as the Diné, arrived in the area.

The first documented case of Europeans viewing the Grand Canyon occurred in September 1540. That year, Hopi guides led a group of 13 Spanish soldiers under Captain Garcia Lopez de Cardenas to find the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola for his superior officer, the conquistador Francisco Vasquez de Coronado.

The group arrived at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon between Desert View and Moran Point and saw a river below. Pablo de Melgrossa, Juan Galeras, and a third soldier descended one-third of the way into the canyon, but were forced to return due to a lack of water. It is speculated that their Hopi guides were reluctant to lead them to the river, as they surely knew the route to the canyon floor.

Failing to find gold, the Spaniards soon left the area, and it would be more than two centuries before Europeans revisited it.

In 1776, Fathers Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Silvestre Velez de Escalante traveled with Spanish soldiers to explore southern Utah. The group traveled along the North Rim of the Canyon in Glen and Marble Canyons, searching for a route from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to Monterey, California.

The next Europeans to reach the canyon were James Ohio Pattie and a group of American trappers in 1826. However, little or no documentation exists of their travels.

The signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 ceded the Grand Canyon region to the United States. Jules Marcou of the Pacific Railroad Survey made the first geologic observations of the canyon and the surrounding area in 1856.

At about the same time, Jacob Hamblin, a Mormon missionary, was sent by Brigham Young to locate an easy river crossing site in the canyon. Building good relations with local Native Americans and white settlers, he discovered the sites of what would become Lee’s Ferry and Pearce Ferry—the only two sites suitable for ferry operations.

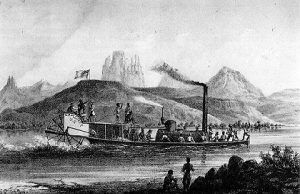

In 1857, a U.S. War Department expedition led by Lieutenant Joseph Ives investigated the area’s potential for natural resources, sought railroad routes to the west coast, and assessed the feasibility of an upriver navigation route from the Gulf of California. The group traveled in a stern-wheeler steamboat named the Explorer. After two months and 350 miles of difficult navigation, his party reached Black Canyon. In the process, the Explorer struck a rock and was abandoned. The group then traveled eastwards along the South Rim of the Grand Canyon.

A man of his time, Ives discounted his impressions of the canyon’s beauty. He declared it and the surrounding area “altogether valueless,” remarking that his expedition would be “the last party of whites to visit this profitless locality.”

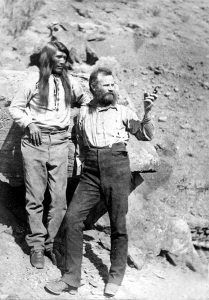

Attached to Ives’ expedition was geologist John Strong Newberry, who had a very different impression of the canyon. After returning, Newberry convinced fellow geologist John Wesley Powell that a boat run through the Grand Canyon to complete the survey would be worth the risk. Powell was a major in the United States Army and a veteran of the Civil War, a conflict that resulted in the loss of his right forearm in the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee.

More than a decade after the Ives Expedition, and with the help of the Smithsonian Institution, Powell led the first of the Powell Expeditions to explore the region and document its scientific features. On May 24, 1869, nine men set out from Green River Station in Wyoming down the Colorado River and through the Grand Canyon. This first expedition was poorly funded; consequently, no photographer or graphic artist was included. While in the Canyon of Lodore, one of the group’s four boats capsized, spilling most of their food and scientific equipment into the river. This shortened the expedition to 100 days. Tired of being constantly cold, wet, and hungry and not knowing they had passed the worst rapids, three of Powell’s men climbed out of the great chasm in what is now called Separation Canyon. Once out of the canyon, all three were killed by a band of Paiutes who thought they were miners who had recently molested one of their females. All those who stayed with Powell survived and successfully ran most of the canyon.

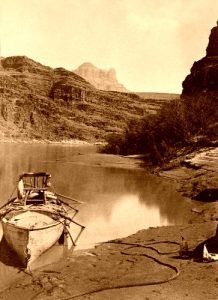

Two years later, a much better-funded Powell-led party returned with redesigned boats and a chain of several supply stations along their route. This time, photographer E.O. Beaman and 17-year-old artist Frederick Dellenbaugh were included. Beaman left the group in January 1872 over a dispute with Powell. Beaman’s replacement, James Fennemore, quit in August of that same year due to poor health, leaving boatman Jack Hillers as the official photographer (nearly one ton of photographic equipment was needed on-site to process each shot). After the river voyage, the renowned painter Thomas Moran joined the expedition in the summer of 1873 and thus saw the canyon only from the rim. His 1873 painting, “Chasm of the Colorado,” was purchased by the United States Congress in 1874 and hung in the Senate lobby.

John D. Lee (of Mountain Meadows Massacre fame) was the first person to cater to travelers to the canyon. In 1872, he established a ferry service at the confluence of the Colorado and Paria rivers. Lee was in hiding, having been accused of leading the Mountain Meadows Massacre in 1857. He was tried and executed for this crime in 1877. During his trial, he hosted members of the Powell Expedition, who were waiting for their photographer, Major James Fennemore, to arrive (Fennemore took the last photo of Lee sitting on his coffin). Emma, one of Lee’s nineteen wives, continued the ferry business after her husband’s death. In 1876, Harrison Pearce established another ferry service at the canyon’s western end.

The Powell expeditions systematically cataloged rock formations, plants, animals, and archaeological sites. Photographs and illustrations from the Powell expeditions greatly popularized the canyonlands region of the southwestern United States, particularly the Grand Canyon. Powell later used these photographs and illustrations in his lecture tours, making him a national figure. Rights to reproduce 650 of the expeditions’ 1,400 stereographs were sold to help fund future Powell projects. In 1881, he became the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Geologist Clarence Dutton followed up on Powell’s work in 1880–1881 with the newly formed U.S. Geological Survey. Painters Thomas Moran and William Henry Holmes accompanied Dutton, who was busy drafting detailed descriptions of the area’s geology. The report from the team’s effort was titled “A Tertiary History of the Grand Canyon District with Atlas” and was published in 1882. This, along with subsequent geological studies, uncovered the geology of the Grand Canyon area and helped advance the science. The Powell and Dutton expeditions helped increase interest in the canyon and the surrounding region.

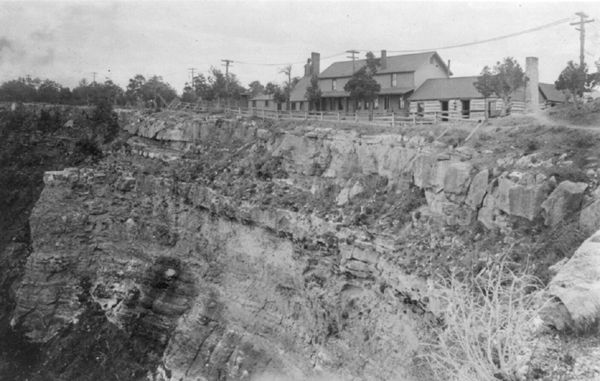

In the 1870s and 1880s, miners began to stake claims in the canyon, hoping that previously discovered deposits of asbestos, copper, lead, and zinc would be profitable. However, access to the canyon and the difficulties in removing the ore made the exercise not worth the effort. However, the mining activities significantly improved the already existing Indian trails within the canyon.

During these early years of the canyon’s exploration, the Indians lived in and near the great chasm until 1882. It was at this time that the United States Army began to move them onto reservations, bringing an end to the Indian Wars. The Havasupai and Hualapai are descended from the Cerbat and live in the immediate area. In the western part of the current park, Havasu Village is likely one of the oldest continuously occupied settlements in the contiguous United States. Adjacent to the eastern part of the park is the Navajo Nation, the largest reservation in the United States.

The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad completed a rail line to Flagstaff, the largest city in the area, in 1882. The following year, stagecoaches began bringing tourists from Flagstaff to the canyon on an eleven-hour journey.

The two-room Farlee Hotel opened in 1884 near Diamond Creek and operated until 1889, when its owner, Louis Boucher, opened a more prominent hotel at Dripping Springs. John Hance opened his ranch near Grandview to tourists in 1886, only to sell it nine years later. He then embarked on a long career as a Grand Canyon guide and, in 1896, became the local postmaster.

William Wallace Bass established a tent-house campground in 1890. Bass Camp had a small central building with shared facilities, including a kitchen, dining room, and sitting room. Located 20 miles west of the Grand Canyon Railway, the rates were $2.50 per day, and his stagecoach road carried patrons from the train station to the camp.

The Grand Canyon Hotel Company was incorporated in 1892 and charged with building services along the stage route to the canyon.

On February 20, 1883, President Benjamin Harrison established the Grand Canyon as a National Forest preserve, which provided some environmental protection, although logging and mining were still permitted.

In 1896, the same man who bought Hance’s Grandview ranch opened the Bright Angel Hotel in Grand Canyon Village.

Tourism increased significantly in 1901 when a spur of the Santa Fe Railroad from Williams, Arizona, to Grand Canyon Village was completed. The 64-mile trip cost $3.95. The development of formal tourist facilities, especially at Grand Canyon Village, increased dramatically.

The first automobile was driven to the Grand Canyon in 1902, when Oliver Lippincott of Los Angeles, California, drove his car from Flagstaff to the South Rim. Lippincott, a guide, and two writers set out on the afternoon of January 4, anticipating a seven-hour journey. Two days later, the hungry and dehydrated party arrived at their destination; the countryside was just too rough for the 10-horsepower automobile.

The Cameron Hotel opened in 1903, and its owner began charging a toll to use the Bright Angel Trail.

The Kolob Brothers, Emery and Ellsworth, built a photographic studio on the South Rim at the trailhead of Bright Angel Trail in 1904. Hikers and mule caravans descending the canyon would stop at the Kolob Studio to have their photographs taken. The Kolob Brothers processed the prints before their customers returned to the rim. Later, the Kolob Brothers would be the first to make a motion picture of a river trip through the canyon.

The Fred Harvey Company developed the luxury El Tovar Hotel on the South Rim in 1905. The hotel was named after Don Pedro de Tovar, who, according to tradition, was the Spaniard who learned of the canyon from the Hopi and informed Coronado of it. Charles Whittlesey designed the Arts and Crafts-style rustic hotel complex, built with logs and local stone, for $250,000 for the hotel and another $50,000 for the stables. The El Tovar was owned by the Santa Fe Railroad and operated by its chief concessionaire, the Fred Harvey Company.

In 1905, the Harvey Company hired Mary Colter to design and oversee the building of the Hopi House. In 1910, the Fred Harvey Company offered her a permanent position as an architect and interior designer of Harvey facilities. She served in that role for the next 38 years, often working in rugged conditions to complete 21 landmark hotels, commercial lodges, and public spaces for the Fred Harvey Company.

In subsequent years, Colter designed and oversaw the construction of additional Fred Harvey establishments in the canyon, including the Lookout in 1914, Hermits Rest in 1914, Phantom Ranch in 1922, the Watchtower in 1932, and the Bright Angel Lodge in 1935.

A cable car system spanning the Colorado River began to operate at Rust’s Camp, located near the mouth of Bright Angel Creek, in 1907.

The Grand Canyon was designated a U.S. National Monument on January 11, 1908. Opponents, such as land and mining claim holders, blocked efforts to reclassify the monument as a U.S. National Park for 11 years. Grand Canyon National Park was finally established as the 17th U.S. National Park by an Act of Congress signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on February 26, 1919. The National Park Service declared the Fred Harvey Company the official park concessionaire in 1920 and bought William Wallace Bass out of business.

In the late 1920s, the North Kaibab suspension bridge over the Colorado River established the first rim-to-rim access. Paved roads did not reach the less-popular, more remote North Rim until 1926. As a result, the area, at a higher elevation, is closed to winter weather from November to April.

The Grand Canyon Lodge opened on the North Rim in 1928. In the winter of 1932, a fire destroyed much of the lodge; however, it was rebuilt and reopened in 1937. Another fire in July of 2025 destroyed the Grand Canyon Lodge again.

Bright Angel Lodge and the Auto Camp Lodge opened on the South Rim in 1935.

Trains remained the preferred mode of travel to the canyon until they were surpassed by automobiles in the 1930s. Finally, competition with the automobile forced the Santa Fe Railroad to cease operation of the Grand Canyon Railway in 1968. Only three passengers were on the last run. However, the railway was restored and service was reintroduced in 1989, and it has since carried hundreds of passengers per day.

Today, about five million people visit more than 1,900 square miles of the Grand Canyon National Park annually. While at the park, you can enjoy its numerous hiking trails, mule rides down the Bright Angel Trail, river rafting, fishing, and camping. There are also about 2,000 known Ancient Puebloan archaeological sites within park boundaries. Numerous visitor centers offer information, and lodging and dining options are available within the park.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2025.

Contact Information:

Grand Canyon National Park

P.O. Box 129

Grand Canyon, Arizona 86023

928-638-7888

See our Grand Canyon National Park Gallery HERE.

Aerial view of the Colorado River as it winds through the deep gorge at Grand Canyon National Park by Carol Highsmith.

Also See:

Colorado River – A Hardworking Waterway

Mary Colter – Architect of the West

Harvey Hotels & Restaurants Along the Rails

National Parks, Monuments & Historic Sites

See Sources.