The Fred Harvey Company owned the popular Harvey House chain of restaurants, hotels, and other hospitality businesses alongside railroads in the late 1800s. It was founded in 1876 by Fred Harvey to cater to the growing number of train passengers. These facilities were well-renowned for their service quality, exceeding the railroad passengers’ needs. Several historic structures remain today.

Fred Harvey, born June 27, 1835, was just 15 years old when he emigrated to the United States from Liverpool, England. He first worked as a dishwasher in New York for just $2 daily. Saving his money, he soon moved to New Orleans, Louisiana, where he worked again in the restaurant business, learning the trade from the ground up.

In 1853, he moved to St. Louis, Missouri. Five years later, he and a partner named William Doyle opened the Merchants Dining Saloon and Restaurant in St. Louis. In 1859, he married his wife Ann, and the couple had a son the following year.

Unfortunately, when the Civil War broke out in 1861, his partner took all their money and ran off to join the Confederacy. With no patrons coming through the door, Harvey was broke.

He soon took a succession of jobs on riverboats before working for the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad, which the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad eventually purchased. He ascended the corporate ladder and was transferred to Leavenworth, Kansas, which would remain his home.

During this time, the young entrepreneur noticed that the lunchrooms serving rail passengers were deplorable, and most trains did not have dining cars, even on extended trips. The custom at the time was typical to make dining stops every 100 miles or so. Sometimes there would be a restaurant at the station, but more often than not, there was nothing to feed the hungry travelers. The dining stops were also short, no longer than an hour, and the passengers were expected to find a restaurant, order their meal, and get served in this short amount of time. When the train was ready to go, it left, often leaving passengers stranded at the station. Those who succeeded found the fare available at the train stops less appetizing.

Seeing all this, Fred Harvey drew on his prior restaurant experience and came up with a new idea. However, it was refused when he approached his manager about building a network of restaurants along the railroad line. Instead, in 1873, he began a business venture with Jasper “Jeff” S. Rice to set up three railroad eating houses in Lawrence, Kansas; Wallace, Kansas; and Hugo, Colorado, on the Kansas-Pacific Railroad. The café operation ended within a year.

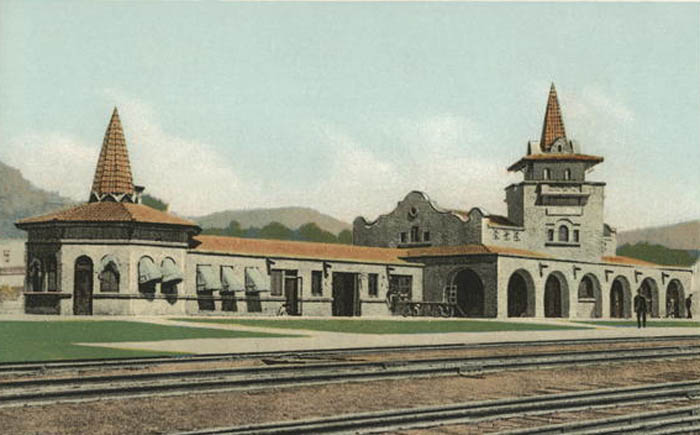

However, Harvey was still convinced of the potential profits from providing high-quality food and service experience at railroad eating houses. He got his chance when he met with Charles Morse, superintendent of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad. After pitching his idea, Morse, a gourmet, loved the concept. The railroad subsequently contracted with Harvey for several eating houses on an experimental basis. Morse would not charge Harvey rent in the agreement, which was sealed only with a handshake. Harvey began by taking over the 20-seat lunchroom at the Topeka, Kansas, Santa Fe Depot Station, which opened under his leadership in January 1876. Harvey’s business focused on cleanliness, service, reasonable prices, and good food. It was an immediate success. Before long, there were more cafes along the line.

The old Harvey House Hotel and Restaurant in Florence, Kansas, now serves as a museum. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

Impressed with his work, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe soon turned over control of food service along the rail line. The Harvey Houses became the first restaurant chain in the U.S., with the Topeka depot becoming the training base for the new chain along the Santa Fe Route. Soon Harvey lunchrooms extended from Kansas to California. Harvey himself engineered a telegraph system that allowed the train to let him know its estimated time of arrival, thereby allowing his restaurant staff to be prepared and to serve the guests quickly.

In 1877, Harvey purchased and opened his first hotel in Peabody, adding fine accommodations. The next year, he started the first of his eating house-hotel establishments along the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad tracks in Florence, Kansas.

By the early 1880s, Harvey operated 17 restaurants along Santa Fe’s main line.

By 1883, Harvey Company restaurants were operating with reasonable effectiveness. However, some out west were plagued by inconsistent service delivery problems, despite the standards Mr. Harvey had established. His all-male workforce was often as wild as the west was. They were often prone to absenteeism, drunkenness, rude behavior, and fighting — none endeared them to the genteel customer segment Harvey sought. A turning point came when Fred Harvey fired all of the waiters, and the manager, at Raton, New Mexico, after a drunken brawl. The newly hired manager requested permission to replace the dismissed rowdies with female staff members.

Though Harvey was adamant about using standard processes across locations, he was open to new ideas, especially when they could be tested. Harvey approved the new hiring criteria and quickly saw the women’s value. From this idea, the “Harvey Girls” were implemented.

Fred Harvey began to recruit women in newspaper ads across the nation. To qualify as one of the “Harvey Girls,” the women had to have at least an eighth-grade education, good moral character, good manners, be neat and articulate, and be single. They were young women between 18 and 30, most of whom Harvey recruited from the East Coast and Midwest.

Harvey paid good wages, as much as $17.50 per month, with free room, board, and uniforms. In return for employment, the Harvey Girls would agree to a minimum six to nine-month contract, abide by all company rules during the term of employment, move to locations where the company needed them, and agree not to marry during their employment. If they married, they would forfeit half their base pay.

When hired, they were given a free rail pass to their chosen destination. The Harvey girls wore a black shirtwaist dress that hung no more than eight inches off the floor, a perfectly starched white apron and cap, opaque black stockings, and black shoes. Their hair had to be restrained in a net and tied with a regulation white ribbon, and makeup of any sort was prohibited, as was chewing gum while on duty.

In an era when there were few career opportunities for women apart from nursing and school teaching, Harvey House employment provided a new option. Many Harvey girls were earning needed income to support the families they left behind. Harvey knew these women and their families would require assurance that their reputations would remain intact in the Wild West, where many other single women were either prostitutes or dance hall girls.

Harvey built comfortable dormitories, imposed strict curfews, and specified behavioral rules for on and off work. The girls were supervised by the most senior Girl, who enforced curfews and chaperoned male visits. As such, Harvey girls generally enjoyed virtuous reputations and were sometimes credited with civilizing the west by bringing good manners and wholesomeness. Within no time, these became much sought-after jobs. Roughly 5,000 Harvey Girls moved out West to work. The Harvey girls were one of Fred Harvey’s most enduring legacies.

The restrictions maintained the clean-cut reputation of the Harvey Girls and made them even more marriageable. Cowboy philosopher Will Rogers once said:

“In the early days, the traveler fed on the buffalo. For doing so, the buffalo got his picture on the nickel. Well, Fred Harvey should have his picture on one side of the dime and one of his waitresses with her arms full of delicious ham and eggs on the other side ‘cause they have kept the West supplied with food and wives.”

The workforce at each Harvey House included a chef, assistant chefs, a butcher, pantry girls, busboys, a housemaid, and a crew of 15-30 waitresses. Each role was clearly specified, but Harvey allowed some movement across lines when supply and demand relationships required it. The Harvey girls became the frontline centerpiece of each restaurant’s staff.

By the late 1880s, there was a Harvey establishment every 100 miles along the Santa Fe line; the distance was equivalent to when trains needed to refuel and load water. Harvey House establishments provided a clean, safe place to relax and enjoy a good meal in sophisticated surroundings. Where beans and biscuits had been the norm, diners could dine on thick, juicy steaks and hot, crispy hash browns. Meals were served on tables outfitted with Irish linens, silver table service, and fine china, with excellent food and reasonable prices. To add to the sense of gentility, Harvey mandated that all men in the dining room must wear coats. A supply of dark alpaca coats was always on hand to ensure no one would be turned away.

At some point, the railroad agreed to convey fresh meat and produce free of charge to any Harvey House via its own private line of refrigerator cars, the Santa Fe Refrigerator Despatch. These railroad cars contained food shipped from every corner of the U.S. The Harvey Company also maintained two dairy facilities, the larger one in Las Vegas, New Mexico, to ensure a consistent and adequate supply of fresh milk.

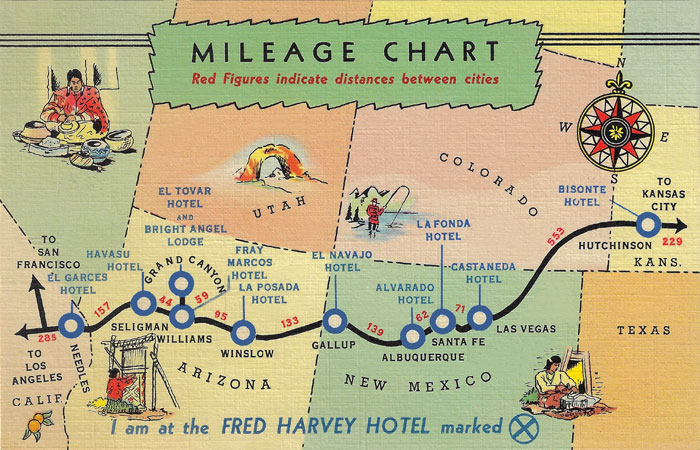

At its peak, there were 84 Harvey Houses, all of which catered to wealthy and middle-class visitors alike and Harvey became known as “the Civilizer of the West.”

In the 1890s, the Santa Fe Railway began including dining cars on some of its trains, with Harvey getting the contract for the food service. At that time, the railroad advertising proclaimed “Fred Harvey Meals All the Way.”

In the early 1900s, Fred Harvey hired architect Mary Colter to design influential landmark hotels in Santa Fe and Gallup, New Mexico, and Winslow, Arizona, at the South Rim and at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. The rugged, landscape-integrated design principles of Colter’s work influenced a generation of subsequent western American architecture.

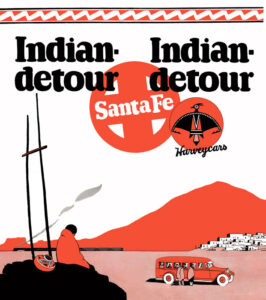

At about the same time, the Fred Harvey Company created an “Indian Department,” which commissioned artists and photographers to convey the exoticism of Native Americans in the Southwest. The images were printed on everything from menus to brochures to promote Indian Country and Harvey’s tourist enterprises. The company also employed Native Americans to demonstrate rug weaving, pottery, jewelry making, and other crafts at his Southwest hotels.

Fred Harvey continued to improve his service until he died in 1901 when his sons took over the company. At the time of his death, 47 Harvey House restaurants, 15 hotels, and 20 dining cars in 12 states were operating on the Santa Fe Railway.

Mary Colter began working full-time for the company in 1910, moving from interior designer to architect. For the next 38 years, Colter served as chief architect and decorator for the Fred Harvey Company. As one of the country’s few female architects and one of the most outstanding, Colter often worked in rugged conditions to complete 21 landmark hotels, commercial lodges, and public spaces for the Fred Harvey Company. Seeking to incorporate her architecture into the natural splendor of the Grand Canyon, she drew from its beauty and focused on authenticity. Hopi House and Bright Angel Lodge, both on the south rim of the Canyon, are prime examples of her work.

After World War I, when people began to travel in automobiles, the company gradually declined. This, coupled with the introduction of faster, more luxurious trains requiring fewer stops, Harvey House restaurants closed in smaller towns. Those in larger towns remained and were frequented by car travelers. However, most Harvey Houses did not have the volume to sustain operating profits without a predictable, consistent number of passengers. The Harvey Company continued operating some dining cars for the Pullman Company, but this business declined, as well, with the demise of train ridership.

Despite the decline in passenger train patronage, the company survived and prospered by marketing its services to the motoring public. Moving away from full reliance on train passengers, the company began to package motor trips of the southwest, including tours of Indian villages and the Grand Canyon, especially after it became a national park in 1919. After 1926, Harvey Cars were used to provide the “Indian Detours,” chauffeured interpretive tours that guests at his Southwest hotels were ferried in comfortable Harvey Cars for one to three-day excursions into Indian settlements in New Mexico and Arizona. These tours provided an authentic Native American experience by having actors stage a particular lifestyle in the desert. Fred Harvey’s son Ford began the series of guided tours, and the company purchased a hotel in Santa Fe called La Fonda, which became headquarters for the Indian Detours. These “Indian Detours” continued into the 1940s.

During the Great Depression, the Harvey Company suffered along with the rest of the nation, as people couldn’t afford to travel. However, Bright Angel Lodge at the Grand Canyon was completed in 1935, and other Harvey Houses were built during the depression.

Beginning in the 1930s, the Fred Harvey Company began expanding into other locations beyond the reach of the Santa Fe Railroad and often away from rail passenger routes. Restaurants were opened in the Chicago Union Station (the largest facility owned by Harvey), San Diego Union Station, the San Francisco Bus Terminal, the Albuquerque International Airport, and the Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal in 1939, which could accommodate nearly 300 diners.

The declining trend was reversed with the commencement of World War II. Suddenly the trains were filled with troops that the Harvey Houses began to feed. At that time, many closed Harvey Houses were reopened and became mess halls for the troops traveling the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad. However, the loss of many Harvey employees to the war effort and supply disruptions left ‘‘Harvey a fragmented system where the standards and quality of food and personnel fluctuated from house to house.”

In 1943, it is estimated that the Fred Harvey Company served more than one million meals each month in dining cars and Harvey Houses. However, by 1948, all but a handful of Harvey Houses had permanently closed.

In 1946, the Harvey Girls were immortalized in the MGM musical namesake movie, The Harvey Girls, starring Judy Garland.

By the 1950s, the railroads were cutting back as newer and better highways were being built across the nation and people began to travel more by air. Passenger trains declined quickly, and railroads gradually began to eliminate passenger service. In the late 1950s, the Harvey Company began to operate the new landmark Illinois Tollway “Oasis,” which were rest stops built on bridges above Interstate 294 in the Chicago suburbs.

In 1954, the Harvey family purchased the Grand Canyon hotels from the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, thus ensuring that the Fred Harvey Company would continue to generate revenue. In 1966, the Fred Harvey Company purchased the Furnace Creek Inn, near Death Valley National Park, from U.S. Borax.

Harvey Houses continued to be built and operated into the 1960s. The hotel and restaurant chain operated under the leadership of his sons and grandsons until 1965. In 1968, the Hawaii-based Amfac Corporation bought the Harvey Company, applying its high standards to Amfac’s list of hotel and resort properties worldwide. When the Harvey Company was sold, it was the sixth largest food retailer in the United States. Amfac was renamed Xanterra Parks & Resorts in 2002. Xanterra purchased the Grand Canyon Railway and its properties in 2006.

Though most of the original Harvey Houses and hotels are gone, a few survive. Most notable are the El Tovar Hotel, built in 1905, and the Bright Angel Lodge, built in 1935, on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. The Fray Marcos Hotel in Williams, Arizona, built as a Harvey House in 1908, now houses a gift shop, offices, and the train depot for the Grand Canyon Railway and Hotel. The new hotel nearby reflects the style of the original. Xanterra operates these hotels and the Grand Canyon Railway and Hotel.

Painted Desert Inn in the middle of Petrified Forest National Park opened in 1940. However, it was short-lived, as World War II slowed travel and closed in 1942. Five years later, the Fred Harvey Company took over management and hired Mary Colter to renovate the property; and the legendary Harvey Girls were brought to the Petrified Forest. The property operated until 1963. In 1987, it was declared a National Historic Landmark; the property was rehabilitated and returned to its former glory. It serves as a museum today.

The La Posada in Winslow, Arizona, built in 1929, is still in operation, providing many Route 66 travelers with accommodations.

Fred Harvey is credited with being the first restaurant chain in the United States and successfully bringing new higher standards of civility and dining to a region widely regarded in the era as “the Wild West.” His company also became a leader in promoting tourism in the American Southwest in the late 19th century. Fred Harvey was also a postcard publisher, touted as “the best way to promote your Hotel or Restaurant.” Most postcards were published in cooperation with the Detroit Publishing Company.

A Fred Harvey Museum is located in the former Harvey residence in Leavenworth, Kansas.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Harvey Hotels & Restaurants on Route 66

Railroads & Depots Photo Gallery

Sources:

Browna, Karen A. and Hyer, Lea Hyer, Archeological benchmarking: Fred Harvey and the service profit chain, 2007

Fred Harvey and the Harvey Girls

Harvey Houses

Kansapedia

Wikipedia – Fred Harvey

Wikipedia – Fred Harvey Company

Xanterra