By Colonel Henry Inman, 1897

William Becknell blazes the Santa Fe Trail

In 1812 Captain William Becknell, who had been on a trading expedition to the country of the Comanche in the summer of 1811, and had done remarkably well, determined the next season to change his objective point to Santa Fe, and instead of the tedious process of bartering with the Indians, to sell out his stock to the New Mexicans. Successful in this, his first venture, he returned to the Missouri River with a well-filled purse and intensely enthusiastic over the result of his excursion to the newly found market.

Excited listeners to his tales of enormous profits were not lacking, who, inspired by the inducement he held out to them, cheerfully invested five thousand dollars in merchandise suited to the demands of the trade and were eager to attempt with him, the passage of the great plains. In this expedition, there were thirty men, and the amount of money in the undertaking was the largest that had yet been ventured.

The progress of the little caravan was without extraordinary incident until it arrived at “The Caches” on the Upper Arkansas River. There, Becknell, who was, in reality, a man of the then “Frontier,” bold, spirited, and endowed with excellent sense, conceived the ridiculous idea of striking directly across the country for Santa Fe through a region unexplored; his excuse for this rash movement being that he desired to avoid the rough and circuitous mountain route he had traveled on his first trip to Taos, New Mexico.

His arrogance in abandoning the known for the unknown was severely punished, and his brave men suffered untold misery, barely escaping with their lives from the terrible straits. Not having the remotest conception of the region through which their new trail was to lead them, and naturally supposing that water would be found in streams or springs when they left, they neglected to supply themselves with more than enough of the precious fluid to last a couple of days. At the end of that time, they learned, too late, that they were in the midst of a desert, with all the tortures of thirst threatening them.

Without a tree or a path to guide them, they took an irregular course by observing the North Star and the unreliable needle of a pocket compass. There was a total absence of water, and when what they had brought with them in their canteens from the river was exhausted, thirst began its horrible office. In a short time, both men and animals were mentally bordering on distraction. To alleviate their acute torment, the dogs of the train were killed, and their blood, hot and sickening, eagerly swallowed; then the ears of the mules were cut off for the same purpose, but such a substitute for water only added to their sufferings.

They would have perished had not a buffalo bull that had just come from the Cimarron River, where he had gone to quench his thirst, suddenly appeared, to be immediately killed and the contents of his stomach swallowed with avidity. It is recorded that one of those who partook of the vile liquid said afterward, “nothing had ever passed his lips which gave him such exquisite delight as his first draught of that filthy beverage.”

Although they were near the Cimarron River, where there was plenty of water, which but for the affair of the buffalo they never would have suspected, they decided to retrace their steps to the Arkansas River.

Before they started on their retreat, however, some of the strongest of the party followed the trail of the animal that had saved their lives to the river, where, filling all the canteens with pure water, they returned to their comrades, who were, after drinking, able to march slowly toward the Arkansas River.

Following that stream, they finally arrived at Taos, having experienced no further trouble, but missed the trail to Santa Fe and had their journey significantly prolonged by the foolish endeavor of the leader to make a shortcut.

As early as 1815, Auguste P. Chouteau and his partner, with a large number of trappers and hunters, went out to the valley of the Upper Crossing to trade with Indians and trap on the numerous streams of the contiguous region.

The island on which Chouteau established his trading post and which bears his name even to this day is in the Arkansas River on the boundary line of the United States and Mexico. It was a beautiful spot, with a rich carpet of grass and delightful groves, and on the American side was a heavily timbered bottom.

While occupying the island, Chouteau and his old hunters and trappers were attacked by about 300 Pawnee Indians, whom they repulsed with the loss of thirty killed and wounded. These Indians afterward declared that it was the most fatal affair in which they were ever engaged. It was their first acquaintance with American guns.

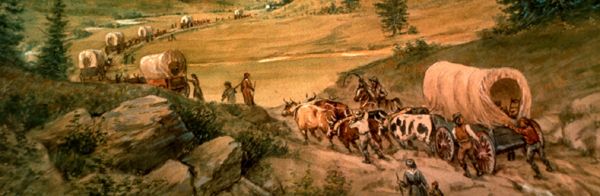

The general character of the early trade with New Mexico was founded on the caravan system. She depended upon the remote ports of old Mexico, where was transported, on the backs of the patient burro and mule, all that was required by the primitive tastes of the primitive people; a very tedious and slow process, and the limited traffic westwardly across the great plains was confined to this fashion. At the date of the legitimate and substantial commerce with New Mexico, in 1824, wheeled vehicles were introduced, and traffic assumed an importance it could never have otherwise attained, and which now, under the vast system of railroads, has increased to dimensions little dreamed of by its originators nearly three-quarters of a century ago.

It was eight years after Pursley’s pilgrimage before the trade with New Mexico attracted the attention of speculators and adventurers. Robert McKnight, James Baird, and Samuel Chambers, with about a dozen comrades, started with a supply of goods across the unknown plains, and by good luck, arrived safely at Santa Fe. Once under the jurisdiction of the Mexicans, however, their trouble began. All the in the party were arrested as spies, their wares confiscated, and themselves incarcerated at Chihuahua, where the majority of them were kept for almost a decade. Beard and Chambers, having by some means escaped, returned to St. Louis in 1822, and, notwithstanding their dreadful experience, told of the prospects of the trade with the Mexicans in such glowing colors that they induced some individuals of small capital to fit out another expedition, with which they again set out for Santa Fe.

It was too late in the season; they succeeded, however, in reaching the crossing of the Arkansas River without any difficulty, but there, a violent snowstorm overtook them, and they were compelled to halt, as it was impossible to proceed in the face of the blinding blizzard. On an island not far from where Cimarron, Kansas, they were obliged to remain for more than three months, during which time most of their animals died for want of food and from the severe cold. When the weather had moderated sufficiently to proceed on their journey, they had no transportation for their goods and were compelled to hide them in pits dug in the earth, after the manner of the old French voyageurs in the early settlement of the continent. This method of secreting furs and valuables of every character is called caching, from the French word “to hide.”

After caching their goods, Beard and the party went on to Taos, where they bought mules and, returning to their caches, transported their contents to their market.

The word “cache” still lingers among the “old-timers” of the mountains and plains and has become a provincialism with their descendants; one of these will tell you that he cached his vegetables on the side of the hill; or if he is out hunting and desires to secrete himself from approaching game, he will say, “I am going to cache behind that rock,” etc.

The place where Baird’s little expedition wintered was called “The Caches” for years, and the name has only fallen into disuse within the last two decades. I remember the great holes in the ground when I first crossed the plains a third of a century ago.

The immense profit upon merchandise transported across the dangerous Trail of the mid-continent to the capital of New Mexico soon excited the cupidity of other merchants east of the Missouri River. When the commonest domestic cloth, manufactured wholly from cotton, brought from two to three dollars a yard at Santa Fe, and other articles at the same ratio to cost, no wonder the commerce with the far-off market appeared to those who desired to send goods there a veritable Golconda.

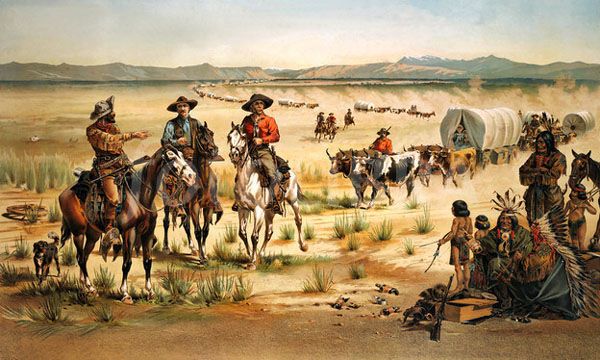

The importance of internal trade with New Mexico and the possibilities of its growth were first recognized by the United States in 1824, the originator of the movement being Mr. Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, who frequently, from his place in the Senate, prophesied the coming greatness of the West. He introduced a bill that authorized the President to appoint a commission to survey a road from the Missouri River to the boundary line of New Mexico and from there on Mexican territory with the consent of the Mexican government. The signing of this bill was one of the last acts of President James Monroe’s official life, and it was carried into effect by his successor, John Quincy Adams. Unfortunately, a mistake was made in supposing that the Osage Indians alone controlled the course of the proposed route. It was partially marked out as far as the Arkansas River, by raised mounds. Travelers continued to use the old wagon trail, but as no negotiations had been entered into with the Comanche, Cheyenne, Pawnee, or Kiowa, these warlike tribes continued to harass the caravans when they arrived in the broad valley of the Arkansas River.

The American fur trade was at its height when the Santa Fe trade was just beginning to assume proportions worthy of notice. The difference between the two enterprises was significantly marked. The fur trade was in the hands of immensely wealthy companies. In contrast, individuals carried on the Santa Fe trade with limited capital, who, purchasing goods in the Eastern markets, had them transported to the Missouri River, where, until the trade to New Mexico became a fixed business, everything was packed on mules. As soon as leading merchants invested their capital, in about 1824, the trade grew into vast proportions, and wagons took the place of the patient mule.

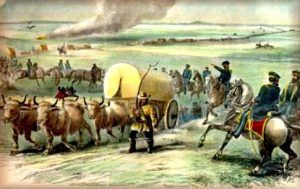

Later, oxen were substituted for mules, it having been discovered that they possessed many advantages over the former, particularly in being able to draw heavier loads than an equal number of mules, especially through sandy or muddy places.

Ox wagons on the trail

For a long time, the traders were in the habit of purchasing their mules in Santa Fe and driving them to the Missouri River. Still, as soon as that useful animal was raised in sufficient numbers in the Southern States to supply the demand, the importation from New Mexico ceased for the reason that the American mule was in all respects an immensely superior animal.

Once mules were an important object of the trade, and those who dealt in them and drove them across to the river on the Trail met with many mishaps; frequently, whole droves, containing from three to five hundred, were stolen by Indians en route.

The latter soon learned that it was a very easy thing to stampede a caravan of mules, for, once panic-stricken, it is impossible to restrain them, and the Indians having started them kept them in a state of rampant excitement by their blood-curdling yells until they had driven them miles beyond the Trail.

A story is told of a small band of 12 men, who, while encamped on the Cimarron River, in 1826, with four good guns among them, were visited by a party of Indians, believed to be Arapaho, who made at first strong demonstrations of friendship and goodwill. Observing the defenseless condition of the traders, they went away but soon returned about 30 strong, each provided with a lasso and all on foot. The chief then began by informing the Americans that his men were tired of walking and must have horses.

Thinking it folly to offer any resistance, the terrified traders told them if one animal apiece would satisfy them, to go and catch them. This they soon did, but finding their request so easily complied with, the Indians held a little conversation together, which resulted in a new demand for more — they must have two apiece! “Well, catch them!” was the acquiescent reply of the unfortunate band; upon which the savages mounted those they had already secured, and, swinging their lassos over their heads, plunged among the stock with a furious yell and drove off the entire herd of nearly 500 head of horses, mules, and asses.

In 1829 the Indians of the plains became such a terror to the caravans crossing to Santa Fe that the United States government, upon petition of the traders, ordered three companies of infantry and one of the riflemen, under the command of Major Bennet Riley, to escort the annual caravan, which that year started from the town of Franklin, Missouri, then the eastern terminus of the Santa Fe trade, as far as Chouteau’s Island, on the Arkansas River, which marked the boundary between the United States and Mexico. The caravan started from the island across the dreary route unaccompanied by troops. They had progressed only a few miles when a band of Kiowa attacked it, then one of the cruelest and bloodthirsty tribes on the plains.

This escort, commanded by Major Riley, and another under Captain Wharton, composed of only sixty dragoons, five years later, were the sole protection ever given by the government until 1843 when Captain Philip St. George Cooke again accompanied two large caravans to the same point on the Arkansas River as did Major Riley fourteen years before.

As the trade increased, the Comanche, Pawnee, and Arapaho continued to commit their depredations, and it was firmly believed by many of the freighters that these Indians were incited to their devilish acts by the Mexicans, who were always jealous of “Los Americanos.”

It was very rarely that a caravan, great or small, or even a detachment of troops, no matter how large, escaped the raids of these bandits of the Trail. If the list of those who were killed outright and scalped, and those more unfortunate who were taken captive only to be tortured and their bodies horribly mutilated, could be collected from the opening of the traffic with New Mexico until the years 1868-69, when General Sheridan inaugurated his memorable “winter campaign” against the allied plains tribes, and completely demoralized, cowed, and forced them on their reservations, about the time of the advent of the railroad, it would present an appalling picture; and the number of horses, mules, and oxen stampeded and stolen during the same period would amount to thousands.

As the excellent narrative of Captain Zebulon Pike is not read as it should be by the average American, a brief reference to it may not be considered supererogatory. The celebrated officer, who was afterward promoted to the rank of major-general, and died in the achievement of the victory of York, Upper Canada, in 1813, was sent in 1806 on an exploring expedition up the Arkansas River, with instructions to pass the sources of Red River, for which those of the Canadian River was then mistaken; he, however, even went around the head of the latter, and crossing the mountains with an almost incredible degree of peril and suffering, descended upon the Rio del Norte with his little party, then but 15 in number.

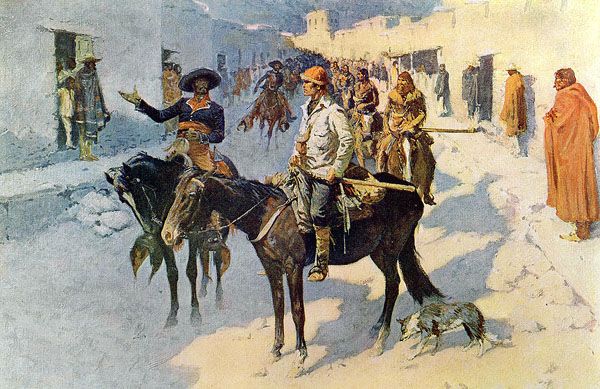

Believing himself now on Red River, within the then assumed limits of the United States, he built a small fortification for his company until the opening of the spring of 1807 should enable him to continue his descent to Natchitoches. As he was really within Mexican territory and only about 80 miles from the northern settlements, his position was soon discovered. A force was sent to take him to Santa Fe, which was effected without opposition by treachery. The Spanish officer assured him that the governor, learning that he had mistaken his way, had sent animals and an escort to convey his men and baggage to a navigable point on Red River and that His Excellency desired very much to see him at Santa Fe, which might be taken on their way.

As soon, however, as the governor had the too confiding captain in his power, he sent him with his men to the commandant general at Chihuahua, where most of his papers were seized, and he and his party were sent under an escort, via San Antonio de Bexar, to the United States.

Many citizens of the remote Eastern States, who were contemporary with Pike, declared that his expedition was in some way connected with the treasonable attempt of Aaron Burr. The idea is simply preposterous; Pike’s whole line of conduct shows him to have been of the most patriotic character; never would he for a moment have countenanced a proposition from Aaron Burr!

After Captain Pike’s report had been published to the world, the adventurers who were inspired by its glowing description of the country he had been so far to explore were destined to experience trials and disappointments of which they had formed no conception.

Among them was a certain Captain William Sublette, a famous old trapper in the era of the great fur companies, and with him a Captain Jedediah Smith., who, although veteran pioneers of the Rocky Mountains, were mere novices in the many complications of the Trail; but having been in the fastnesses of the great divide of the continent, they thought that when they got down on the plains, they could go anywhere. They started with 20 wagons and left the Missouri River without a single one of the party being competent to guide the little caravan on the dangerous route.

From the Missouri River, the Trail was broad and plain enough for a child to follow, but when they arrived at the Cimarron River crossing of the Arkansas River, not a trace of former caravans was visible; nothing but the innumerable buffalo-trails leading from everywhere to the river.

When the party entered the desert, or Dry Route, as it was years afterward always, and very correctly, called in certain seasons of drought, the brave but too confident men discovered that the whole region was burnt up. They wandered on for several days, the horrors of death by thirst constantly confronting them. Water must be had, or they would all perish! At last, Smith, in his desperation, determined to follow one of the numerous buffalo-trails, believing that it would conduct him to water of some character–a lake or pool or even wallow. He left the train alone; asked for no one to accompany him, for he was the very impersonation of courage, one of the most fearless men that ever trapped in the mountains.

He walked on and on for miles when he saw a stream in the valley beneath him on ascending a little divide. It was the Cimarron River, and he hurried toward it to quench his intolerable thirst. When he arrived at its bank, to his disappointment, it was nothing but a bed of sand; the sometimes clear running river was perfectly dry.

Only for a moment, he staggered; he knew the character of many streams in the West; that often their waters run under the ground at a short distance from the surface, and in a moment, he was on his knees digging vigorously in the soft sand. Soon the coveted fluid filtered upwards into the little excavation he had made. He stooped to drink, and in the next second, a dozen arrows from an ambushed band of Comanches entered his body. However, he did not die at once; it is related by the Indians themselves that he killed two of their number before death laid him low.

Captain Sublette and Smith’s other comrades did not know what had become of him until some Mexican traders told them, having got the report from the very savages who committed the cold-blooded murder.

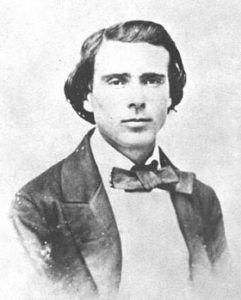

Josiah Gregg

Trader Josiah Gregg, who wrote the book Trail in Commerce of the Prairies in 1844, described it this way:

Every kind of fatality seems to have attended this small caravan. Among other casualties, a clerk in their company, named Minter, was killed by a band of Pawnees, before they crossed the. This, I believe, is the only instance of loss of life among the traders while engaged in hunting, although the scarcity of accidents can hardly be said to be the result of prudence. There is not a day that hunters do not commit some indiscretion; such as straying at a distance of five and even ten miles from the caravan, frequently alone, and seldom in bands of more than two or three together. In this state, they must frequently be spied by prowling savages; so that frequency of escape, under such circumstances, must be partly attributed to the cowardice of the Indians; indeed, generally speaking, the latter are very loath to charge upon even a single armed man, unless they can take him at a decided advantage.

Not long after, this band of Captain Sublette’s very narrowly escaped total destruction. They had fallen in with an immense horde of Blackfeet and Gros Ventres, and, as the traders were literally but a handful among thousands of savages, they fancied themselves for a while in imminent peril of being virtually “eated up.” But as Captain Sublette possessed considerable experience, he was at no loss how to deal with these treacherous savages; so that although the latter assumed a threatening attitude, he passed them without any serious molestation, and finally arrived at Santa Fe in safety.

The virtual commencement of the Santa Fe trade dates from 1822, and one of the most remarkable events in its history was the first attempt to introduce wagons in the expeditions. This was made in 1824 by a company of traders, about eighty in number, among whom were several gentlemen of intelligence from Missouri, who contributed by their superior skill and undaunted energy to render the enterprise completely successful. A portion of this company employed pack-mules; among the rest were owned twenty-five wheeled vehicles, of which one or two were stout road-wagons, two were carts, and the rest Dearborn carriages, the whole conveying some twenty-five or thirty thousand dollars’ worth of merchandise.

Colonel Marmaduke, of Missouri, was one of the party. This caravan arrived at Santa Fe safely, experiencing much less difficulty than they anticipated from the first attempt with wheeled vehicles.

Gregg continues:

The early voyageurs, having but seldom experienced any molestation from the Indians, generally crossed the plains in detached bands, each individual rarely carrying more than two or three hundred dollars’ worth of stock. This peaceful season, however, did not last very long; and it is greatly to be feared that the traders were not always innocent of having instigated the savage hostilities that ensued in after years. Many seemed to forget the wholesome precept that they should not be savages themselves because they dealt with savages. Instead of cultivating friendly feelings with those few who remained peaceful and honest, there was an occasional one always disposed to kill, even in cold blood, every Indian that fell into their power, merely because some of the tribe had committed an outrage either against themselves or friends.

As an instance of this, he relates the following:

In 1826 two young men named McNess and Monroe, having carelessly lain down to sleep on the bank of a certain stream, since known as McNee’s Creek, were barbarously shot, with their own guns, as it was supposed, in the very sight of the caravan. When their comrades came up, they found McNee’s lifeless, and the other almost expiring. In this state, the latter was carried nearly 40 miles to the Cimarron River, where he died, and was buried according to the custom of the prairies, a very summary proceeding, necessarily. The corpse, wrapped in a blanket, its shroud, the clothes it wore, is interred in a hole varying in depth according to the nature of the soil, and upon the grave is piled stones, if any are convenient, to prevent the wolves from digging it up. Just as McNee’s funeral ceremonies were about to be concluded, six or seven Indians appeared on the opposite side of the Cimarron River. Some of the party proposed inviting them to a parley, while the rest, burning for revenge, evinced a desire to fire upon them at once. It is more than probable, however, that the Indians were not only innocent but ignorant of the outrage that had been committed, or they would hardly have ventured to approach the caravan.

Being quick of perception, they very soon saw the belligerent attitude assumed by the company, and therefore wheeled round and attempted to escape. One shot was fired, which brought an Indian to the ground when he was instantly riddled with balls. Almost simultaneously, another discharge of several guns followed, by which all the rest were either killed or mortally wounded, except one, who escaped bearing the news to his tribe.

These wanton cruelties had a most disastrous effect upon the prospects of the trade, for the exasperated children of the desert became more and more hostile to the “pale-faces,” against whom they continued to wage a cruel war for many successive years. In fact, this party suffered a few days very severely afterward. They were pursued by the enraged comrades of the slain savages to the Arkansas River, where they were robbed of nearly a thousand horses and mules.

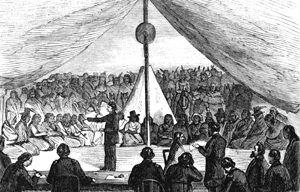

The author of this book, although having but little compassion for the Indians, must admit that, during more than a third of a century passed on the plains and in the mountains, he has never known of a war with the hostile tribes that was not caused by broken faith on the part of the United States or its agents. I will refer to two prominent instances: the outbreak of the Nez Perce and that of the allied plains tribes. With the former, a solemn treaty was made in 1856, guaranteeing to them occupancy of the Wallowa Valley forever. Isaac Stevens, who was governor of Washington Territory at the time, and ex-officio superintendent of Indian affairs in the region, met the Nez Perce, whose chief, “Wish-la-no-she,” an octogenarian, when grasping the hand of the governor at the council said: “I put out my hand to the white man when Lewis and Clark crossed the continent, in 1805, and have never taken it back since.” The tribe kept its word until the white men took forcible possession of the valley promised to the Indians, when the latter broke out, and a prolonged war was the consequence.

In 1867 Congress appointed a commission to treat with the Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Arapaho, appropriating $400,000 for the expenses of the commission. It met at Medicine Lodge in August of the year mentioned and made a solemn treaty, which the commission members, on the part of the United States and the principal chiefs of the three tribes, signed. Congress failed to make any appropriation to carry out the provisions of the treaty, and the Indians, after waiting a reasonable time, broke out, devastated the settlements from the Platte to the Rio Grande, destroying millions of dollars worth of property and sacrificing hundreds of men, women, and children. Another war was the result, which cost more millions, and under General Sheridan, the hostile Indians were whipped into a peace, which they have been compelled to keep.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2021.

Also See:

Santa Fe Trail – Highway to the Southwest

About the Article & Author: Excerpted from the book, The Old Santa Fe Trail, by Colonel Henry Inman, 1897. Please note that the article as it appears here is not verbatim as minor editing has occurred. Henry Inman was well known both as an officer in the U.S. Army and an author dealing with subjects of the Western plains. During the Civil War, Inman was a Lieutenant Colonel, and afterward, he won distinction as a magazine writer. He wrote several books including Old Santa Fe Trail, Great Salt Lake Trail, The Ranch on the Ox-hide, and other similar books dealing with the subjects he knew so well. Colonel Inman left several unfinished manuscripts at his death in Topeka, Kansas, on November 13, 1899.