A Butterfield stage wagon on the trail, early October 1858, in Arizona by William Hayes Hilton. This drawing is a good representation showing the wild mules used to pull the stage wagons on the rougher sections of the trail. Some wild horses were also used.

Had I not just come out over the route, I would be perfectly willing to go back, but I now know what Hell is like. I’ve just had 24 days of it.”

— Waterman Ormsby, special correspondent for the New York Herald, after having made the first westbound trip on the Butterfield Stage.

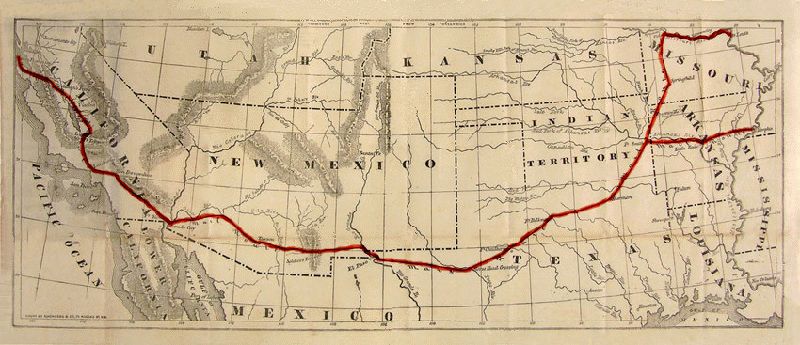

Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company, also known as the Overland Stage Company, was the brainchild of John Butterfield. Through the 1840s and 1850s, mail was carried between the east and west coasts by several private companies, some under federal contract, using various routes, including ocean steamers around South America or overland, across the Isthmus of Panama. But, there was a desire for better and quicker communication. On April 20, 1857, the United States government advertised for bids on a contract for an “Overland Mail Service to California.”

Gerald T. Ahnert, historian and authority on the Overland Mail Company, wrote:

“What was needed was someone with some of the most extensive experience in the United States.”

At the age of 19, John Butterfield, Sr., moved to Utica, New York, and immediately began to work for stage companies. In 1850 he was a founding member of the American Express Company. By 1857, when he bid on the Overland Mail Company contract, he owned and operated 40 stage lines in New York State. Nine bids were made, and Contract No. 12578 was awarded on September 16, 1857, to John Butterfield Sr. of Utica, New York. Why he was chosen was stated by Postmaster General Aaron Brown:

“… a route which no contractor had bid for, but one which, in the judgment of A. V. Brown, of Memphis, “had more advantages than disadvantages than any other.” And, as John Butterfield & Co. had, in the opinion of Brown, “greater ability, qualification, and experience than anybody else to carry out a mail service,” John Butterfield & Co. was selected and preferred…”

Ahnert continued:

“John Butterfield Sr. was the mastermind for the choice of employees to build and manage the Overland Mail Company’s infrastructure from September 16, 1857, to March 20, 1860. Most were from Upstate New York. During this 2 1/2 years, the building of the longest stage line in the world and meeting the requirements of the government contract proved his staging genius.”

The Butterfield stage starts its journey in Tipton, Missouri.

A sound balance was struck for his choice of company directors. About half were associates in upstate New York, who also owned stage lines, and John drew on their experience to aid him in building the infrastructure for the company. It would be expensive to build and stock the trail, so he chose some directors from Adams Express, National Express, Wells, Fargo & Co. Express, and American Express. These companies would act as bankers for loans.

No express companies bid on the contract, as they didn’t have the experience to build and manage a 2,700-mile stage line through the frontier of the largely unsettled southwest.

John Sr. was president of the company from its construction phase until he was voted out on March 20, 1860, because he failed to pay back to banker Wells Fargo & Co. a loan of $162,000. This loan was necessary because the U.S. government failed to acquire the needed funds in the latest appropriations bill to fulfill the quarterly payment. At the March 17 meeting, a resolution proposed that all assets of the Overland Mail Company be turned over to them because of the unpaid debt. John stormed out in protest, and the meeting was postponed. When the March 20 meeting began to settle the issue with John in attendance, a compromise was made for the March 17th resolution to be withdrawn. The Overland Mail Company was allowed to retain its structure and name, but John was voted out as president. William B. Dinsmore, also a director of Adams Express Company, was elected president. Operating finance policymaking for the company would still be made by the directors, including John Butterfield. However, a larger voice would now be had by those that were also directors of the express companies led by Wells, Fargo & Co. Express.

Under the stockholder’s influence in financial matters, the company’s services and morale suffered greatly. A scathing letter dated September 25, 1860, by Overland Mail Company assistant treasurer Hiram S. Rumfield, pointed out the company employee’s displeasure.

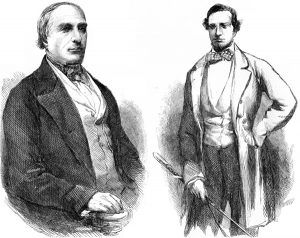

Butterfield had one year to select the route of the trail and station sites and stock the trail before the actual start of the six-year contract on September 16, 1858. For this purpose, he chose his son John Jr. and Marquis L. Kenyon of Rome, New York, who was also a company director.

The company poured about one million dollars into establishing the route. In September 1858, there were 139 stations established. Many had to be built, but some existing establishments were used. When the Overland Mail Company was transferred to the Central Trail on March 2, 1861, 175 Butterfield stations were strung-out along the Southern Overland Trail. About 1,500 employees were needed, and he furnished the trail with 34 Concord stagecoaches and 66 of the lightweight and less expensive celerity stage wagons he designed. These stages were distributed to stations about every thirty miles along the trail. The Concords would be used on the trail through the semi-settled areas from Tipton, Missouri, to Fort Smith, Arkansas, and from Los Angeles to San Francisco, California. The stage wagons would be used on the 1,920 miles of trail through the wild frontier. Butterfield never used his name on any stages, only “Overland Mail Company.” None of his stages exist today. Thousands of mules and horses would be needed, and many used to pull the stage wagons were local wild mules and Mustang horses.

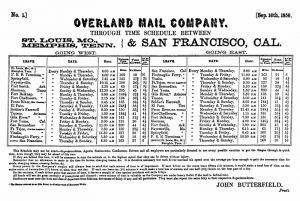

The route was divided into Eastern and Western divisions. These nine divisions were each assigned a Superintendent. This was outlined in Postal Inspector Goddard Bailey’s memo to Postmaster General Aaron Brown in 1858. He was on the first Butterfield stage that left San Francisco ten minutes after midnight on September 14, 1858. The mail started from St. Louis, Missouri, on September 16, 1858.”

As scheduled, mail started from each end of the 2,800-mile-long stretch on September 16, 1858. The passenger fare was $200. The first westbound trip was made in about 24 days. On its westward maiden journey, one of the passengers was a New York Herald special correspondent named Waterman Ormsby, who would report his experiences in several articles. In Springfield, Missouri, Ormsby reported that the mail party switched from a Concord stagecoach to a stronger, canvas-topped wagon. Travelers were in motion day and night, stopping only for meals and to switch out stock or equipment at stations placed from 9-60 miles apart. On approaching a station, the conductor would blow a horn so fresh mules or horses would be ready and waiting. Early in the trip, Ormsby optimistically noted, “we had now gone two hundred and forty-three miles, through, I think, some of the roughest part of the country on the route. . . I find roughing it on the Plains agrees with me.”

John Butterfield Sr.(left), president of the Overland Mail Company, and his son John Jr. (right) about the time they boarded the first Overland Mail Company stagecoach leaving Tipton, Missouri on September 16, 1858. John Jr. was the driver. John Sr. rode as far as Fort Smith, Arkansas, and returned to Tipton on an eastbound stage, then on to his hometown of Utica, New York. From a drawing in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 27, 1858.

Two days later, he changed his mind, stating, “I had thought before we reached this point that the rough roads of Missouri and Arkansas could not be equaled, but, here, Arkansas fairly beats itself. I might say our road was steep, rugged, jagged, rough, and mountainous – and then wish for some more expressive words… Our heavy wagon bounded along the crags as if it would be shaken in pieces every minute and ourselves disemboweled on the spot.”

Ormsby also reported many mule-related delays, “The mules reared, pitched, twisted, whirled, wheeled, ran, stood still, and cut up all sorts of capers.” Sometimes fearing for his life, he would get off the wagon and walk. On one occasion, he was very glad he did, for the harness soon became tangled, the wagon wrecked, and the two lead mules escaped. The wagon driver disentangled the harness and continued the trip with only two mules. Against his better judgment, Ormsby got back on the wagon, although he wrote that “if I had any property, I certainly should have made a hasty will.”

Stages left both the east and west termini every Monday and Thursday at 8:00 a.m. Conductors rode alongside drivers on the stages and were in charge of the mail and passengers. The Stagecoaches carried six passengers inside, while the stage (celerity) wagons often held nine. Each stage carried up to 12,000 letters. By 1859, the average trip had been reduced to about 21.5 days.

During this time, there were few westward routes, and it was imperative to keep the Overland Mail Company Route open for settlers, miners, and businessmen traveling west. The government assigned a detachment from the 9th Kansas Cavalry to guard the route between Independence, Missouri, and California. Gerald T. Ahnert wrote,

“No Butterfield stage was ever held up by outlaws, and no one on his stages was ever killed during the company’s service on the Southern Overland Trail. Only once was a stage attacked by Indians, and that was in Apache Pass, February 4, 1861. The conductor suffered a bullet wound to his leg.”

On March 2, 1861, before the Civil War officially began, an Act of Congress discontinued this southern route, and a new central route from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Placerville, California, called the Central Overland California Route, went into effect. The last Oxbow Route run was made on March 21, 1861.

Ruins of the Pine Creek Station still stand in Guadalupe National Park in southwest Texas by Kathy Alexander.

Afterward, portions of what would become known as the Butterfield Trail were used by the Confederate and the Union armies, leaving some places in the West virtually cut off from outside communication. The Confederate States of America continued to operate parts of the Overland Mail route with limited success from 1861 until early 1862. However, this success would soon be replaced by the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869.

Today, there are still a number of remnants of what was once the country’s largest overland stage company. In Arkansas, the old Elkhorn Tavern, which was destroyed during the Civil War, has been rebuilt and today sits in the Pea Ridge National Military Park. Also in Arkansas is the town of Pottsville, which was built around Pott’s Inn. Pott’s Inn was finished in 1859 and was a popular stop along the Butterfield Stage Route. It continues to stand today as a museum.

In Texas, the remains of a stagecoach stop are still visible at the Hueco Tanks State Historic Site in El Paso, and the Guadalupe Mountains National Park, ruins of an old stage station, can still be seen. In California, the Oak Grove Stage Station in Warner Springs is the only surviving station on the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach line. Nearby, at the Warner Springs Ranch, two original adobe buildings also stand. It is worth noting that the Vallecito Stage Station also survives, rebuilt using original materials in the 1920s and early 1930s. These remnants and numerous historical markers continue to define the old historic trail.

Although there are many government records from 1858 to 1861 that were published in Senate documents by the Postmaster General and reports from newspaper correspondents who were passengers on a Butterfield stage that describe the route and stations, one of the best, according to Gerald Ahnert, a Butterfield Trail historian, recommends is: The Butterfield Overland Mail, Only Through Passenger on the First Westbound Stage, by Waterman L. Ormsby, who was a correspondent for the New York Herald.

Division-Route Information:

| Division | Route | Approximate Miles | Approximate Hours | |

| Division 1 | San Francisco to Los Angeles, California | 462 | 80 | |

| Division 2 | Los Angeles to Fort Yuma, California | 282 | 72.20 | |

| Division 3 | Fort Yuma, California to Tucson, Arizona | 280 | 71.45 | |

| Division 4 | Tucson, Arizona to Franklin (El Paso), Texas | 360 | 82 | |

| Division 5 | Franklin (El Paso) to Fort Chadbourne, Texas | 458 | 126.30 | |

| Division 6 | Fort Chadbourne, Texas to Colbert’s Ferry, Oklahoma | 282.5 | 65.25 | |

| Division 7 | Colbert’s Ferry, Oklahoma to Fort Smith, Arkansas | 192 | 38 | |

| Division 8 | Fort Smith, Arkansas to Tipton, Missouri | 318.5 | 48.55 | |

| Division 9 | Tipton to St. Louis, Missouri | 160 | 11.40 | |

| Totals | 2,795 | 596.35 |

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, with included submission and updates from Gerald T. Ahnert, updated June 2023.

Also See:

John Butterfield – Expanding the Routes in the West

Stagecoaches of the American West

Source – See Resources and Credits