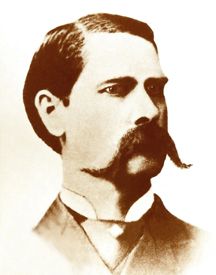

By Wyatt Earp in 1896

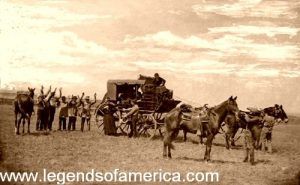

Stagecoach attacked by Indians, Daniel Cavaliere

With his gun across his knee, his treasure box under his feet, and his eyes peering into every patch of chaparral by the roadside, the shotgun messenger played a humble but important part in the economy of frontier life.

Humble, did I say? Well, yes, there was far more danger than profit or honor attached to the work. And yet such a man as a big express company would be sure to single out for safeguarding the treasure entrusted to it, must be a man fitted to fight his way to the top in a community where the sheer scorn of death was the only safeguard of life. So, at least, it would seem.

But of the many daring spirits I have known to imperil their lives in the Wells Fargo messenger service, I can recall only one who clambered to any eminence out of the hurly-burly of frontier life. And even then, it was no very dizzy height that he reached.

Bob Paul, as fearless a man and as fast a friend as I ever knew, graduated from a messengership to the Shrievalty [relating to a sheriff] of Pima county, Arizona, and from that to the United States Marshalship of the Territory. And now he has reft [deprived] himself from the rugged road of officialism to pursue the primrose path of bourgeois contentment.

Bob Paul! I fancy I see him, his well-nourished frame endowed with “fair round belly with fat capon lined,” overseeing his smelting works in Tucson and telling a younger generation about the killing of Bud Philpott.

Bud Philpott used to drive the stage from Tombstone to Tucson when that was the terminus of the Southern Pacific. Later when the railroad reached as far as Benson, Bud’s daily drive was only 28 instead of 110 miles — for which, you may be sure, Bud was duly thankful. The worst part of the road was where it skirted the San Pedro River. There, the track was all sandy and cut up, which made traveling about as exhilarating as riding a rail. But that didn’t perturb Bud half as much as the prospect of a hold-up. That prospect increased by an alarming arithmetical ratio when the boom struck Tombstone and the worst cut-throats on the frontier poured into the camp by hundreds.

Come to think of it; it takes some sand to drive a stage through that kind of country, with thousands of dollars in the front boot and the chance of a Winchester behind every rock. Of course, the messenger had his gun and six-shooters, and he was paid to fight. The driver is paid to drive, and it takes him all his time to handle the lines without thinking of shooting. That was why I always made allowances for Bud as I sat beside him, admiring the accuracy with which he would flick a sand fly off the near leader’s flank or plant a mouthful of tobacco juice in the heart of a cactus as we jolted past it, but never relaxing my lookout for an ambuscade. Indeed I often wondered that we were such good friends, considering that I, custodian of the treasure box, would infallibly draw what fire there was around Bud Philpott’s massive pink ears.

That is part of the cursedness of the shotgun messenger’s life — the loneliness of it. He is like a sheepdog, feared by the flock and hated by the wolves. On the stage, he is a necessary evil. Passengers and drivers alike regard him with aversion; without him and his deadly box, their lives would be 90% safer, and they know it. The bad men, the rustlers — the stage robbers, actual and potential — hate him. They hate him because he is the guardian of property. After all, he stands between them and their desires because they will have to kill him before they can get their hands into the coveted box. Most of all, they hate him because of his shotgun — the homely weapon that makes him the peer of many armed men in a quick turmoil of powder and lead.

The Wells Fargo shotgun is not a scientific weapon. It is not a sportsmanlike weapon. It is not a weapon wherewith to settle an affair of honor between gentlemen. But, oh! in the hands of an honest man hemmed in by skulking outlaws it is a sweet and a thrice-blessed thing. The express company made me a present of the gun with which they armed me when I entered their service, and I still have it. In the severe code of ethics maintained on the frontier, such a weapon would be regarded as legitimate only in the service for which it was designed or in defense of an innocent life encompassed by superior odds. But your true rustler throws such delicate scruples to the wind.

To him a Wells-Fargo shotgun is a most precious thing, and if by hook or crook — mostly crook — he can possess himself of one, he esteems himself a king among his kind. Toward the end of my story last Sunday, I described the killing of Curly Bill. By inadvertency, I said that he opened fire on me with a Winchester. I should have said a Wells Fargo shotgun. Later I will tell you where Curly Bill got that gun.

The barrels of the important civilizing agent under consideration are not more than two-thirds the length of an ordinary gun barrel. That makes it easy to carry and throw upon the enemy, with less danger of wasting good lead because of the muzzle catching in some vexatious obstruction. As the gun has to be used quickly or not at all, this shortness of the barrel is no mean advantage. The weapon furthermore differs from the ordinary gun in being much heavier than to barrel, thus enabling it to carry a big charge of buckshot. No less than twenty-one buckshot are loaded into each barrel. That means a shower of forty-two leaden messengers, each fit to take a man’s life or break a bone if it should reach the right spot. And as the buckshot scatters, the odds are all in its favor. At close quarters the charge will convert a man into a most unpleasant mess, of whom Curly Bill was a conspicuous example. As for range — well, at 100 yards, I have killed a coyote with one of these guns, and what will kill a coyote will kill a stage robber any day.

I have said that I made allowances for poor Bud Philpott. What I mean is that I forgave him for his well-defined policy of peace at any price. Whereof, I will narrate an example not wholly without humor at the expense of us both. We were bowling along the road to Benson one morning when four men jumped suddenly out of the brush that skirted the road a short distance ahead of us, and took their stations, two on one side of the road and two on the other.

“My God, Wyatt, we’re in for it!” gasped Bud, ducking forward instinctively and turning an appealing look on me. “What shall we do?”

“There’s only one thing to be done,” I said. He saw what I meant by the way I handled the gun.

“Ye ain’t surely going to make a fight of it, are ye, Wyatt?” he said anxiously. “It looks kinder tough.”

“Certainly I am,” I said, feeling to see that my six-shooters were where I wanted ’em. “Now listen. The minute they holler `Halt!’ you fall down in the boot, but for God’s sake, keep hold of the lines. I’ll take the two on the left first and keep the second barrel for the pair on your side.”

Now all this had passed quickly, and we were bearing down on the strangers steadily. Bud groaned. “I’ll do what you say,” he protested, “but if I was you I’d let ’em have the stuff and then catch ’em afterward.”

I threw my gun at them as we got within range of the four men. Even as I did so, it flashed across me that they wore no masks, their faces were wondrously pacific, and no sign of a gun peeped out among them. Just as I realized we had been fooled, the four threw up their hands with every appearance of terror, their distended eyes fastened on the muzzle of my gun, their lips moving in voluble appeals for mercy. Bud jammed down the brake and jerked the team onto their haunches, showering valiant curses on the men to whom he had proposed to surrender a moment before.

They were harmless Mexicans searching the brush for some strayed broncos. The impulse that led them to plant themselves by the road on the approach of the stage was sheer idiocy, and they were lucky that it did not cost them their lives. They intended to ask us if we had seen any horses back along the road.

This opera bouffe [comedy] situation was the nearest approach to a hold-up that came within my experience. My brother Morgan, who succeeded me, was equally fortunate. After he left the service, the post was resumed by Bob Paul, whom I had succeeded when he retired to run for Sheriff of Pima county. And then, Bud Philpott ran into the adventure, which capped with tragedy our comedy encounter with the Mexicans.

It was in 1881. The stage left Tombstone at 7 o’clock in the evening with a full load of passengers inside and out and a well-filled treasure box in the front boot. They changed teams as usual at Drew station, fifteen miles out. About three hundred yards further on the road crosses a deep ravine. Just as the horses started up the opposite side of this ravine, the coach following them by its own momentum, a shout of “Halt there!” came from some bushes on the further bank. Before the driver could have halted even if he had wanted to, they started in with their Winchesters, and poor Bud Philpott lurched forward with a gurgle in his throat. Before Bob Paul could catch hold of him, he fell down under the wheels, dragging the lines with him.

“Halt there!” shouted the robbers again.

“I don’t halt for nobody,” proclaimed Bob Paul, with a swear word or two, as he emptied both barrels of his gun in the direction, the shots came from. His judgment was superior to his grammar, for we learned afterward that he had wounded one of the rustlers.

Now things happened quickly on the frontier, where bullets count for more than words, and the greatest difficulty I have encountered in writing these recollections is trying to convey an idea of the rapidity with which one event follows another.

When the first shots were fired, and Philpott fell, the horses plunged so viciously ahead that nothing could have stopped them. In missing the messenger and killing the driver, the robbers had defeated their own plans. As Bob fired, he moved over to Philpott’s seat to get his foot on the brake, thinking it could not improve matters to have the coach overturned while it was under fire. Imagine the horses yanking the coach out of the ravine and tearing off down the road at a breakneck gallop, with the lines trailing about their hoofs. And imagine Bob Paul with his foot on the brake, hearing shots and the cries of frightened passengers behind him and wondering what would happen next.

What did happen was this: The rustlers had made such elaborate plans for the hold-up that they never dreamt of the coach getting away from them. Hence they had tied up their horses in a place where they could not be reached with speed necessary to render pursuit practicable. With all hope of plunder vanished and poor Bud Philpott lying dead in the ravine, these ruffians squatted in the middle of the road and took potshots at the rear of the coach. Several bullets hit the coach, and one mortally wounded an outside passenger.

Such were the coyotes who kenneled in Tombstone during the early ’80s. They did this thing deliberately. It was murder for murder’s sake — for the mere satisfaction of emptying their Winchesters.

The horses ran away for two miles, but luckily they kept the road, and when they pulled up, Bob Paul recovered the lines and drove the rest of the way into Benson, with the dying passenger held upright by his companions on the rear outside seat. The man was a corpse before the journey ended.

At Benson, Bob mounted a swift horse and rode back to Tombstone to notify me of the murders. I was dealing faro bank in the Oriental at the time, but I did not lose a moment in setting out on the trail, although faro bank meant anything upwards of $1,000 a night, whereas man hunting meant nothing more than work and cold lead. An affair like that affected me in a double capacity, for I was not only the Deputy United States Marshal for the district, but I continued in the service of the express company as a “private man.”

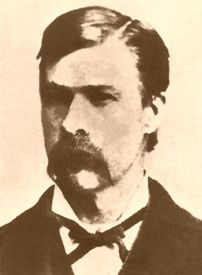

Bat Masterson

So I organized a posse which included my two brothers, Doc Holliday, Bob Paul, and the renowned Bat Masterson — I may have something to say about that prince of frontiersmen at another time — and lost no time in reaching the scene of the shooting. There lay Bud Philpott’s body, mangled by the wheels of the coach he had driven so long. And there, among the bushes, were the masks the robbers had worn. In the middle of the road, we found nearly forty cartridge shells, showing how many shots had been fired in cold blood after the receding coach.

It was easy to find where their horses had been tied, and from there the trail into the mountains was plain enough. But the story of that chase is too long to be told here. I mentioned last Sunday that it consumed seventeen days, and those who read that narrative will remember that this hold-up and that manhunt were the prologues to the bitter and bloody feud that is the central, somber episode of my thirty years on the frontier.

And now for how Curly Bill became the proud proprietor of a Wells-Fargo shotgun. Charley Bartholomew was a messenger who used to run on the coach from Tombstone to Bisbee. Once every month, he was the custodian of a tidy sum of money sent to pay off the miners. Naturally enough, such a prize did not escape the attention of such audacious artists in crime as Frank Stillwell, Pete Spence, Pony Deal, and Curly Bill. With one other, the four desperadoes I have named planned a masterly hold-up which they executed with brilliance and dash. It happened this way:

The coach carrying the miners’ wages had gotten out of Tombstone about twenty miles when the industrious quintette appeared on horseback, three on one side of the road and two on the other. They did not come to close quarters but kept pace with the coach at 300 or 400 yards on either side of the road, pumping into it with their Winchesters and aiming to kill the horses and the messenger. Of course, Bartholomew’s shotgun might as well have been a blowpipe at that range, and if he had a Winchester with him, he did not use it to any effect.

These Indian tactics proved eminently successful in breaking down the nerve of the men on the stage, for after they had run for a mile with an occasional lump of lead knocking splinters out of the coach, Bartholomew told the driver to stop — an injunction which he obeyed very gladly, the robbers came up and made them throw up their hands. They took everything to be taken, which amounted to $10,000, and sundries. Among the sundries was Charlie Bartholomew’s shotgun, with which Curly Bill afterward tried to fill me full of buckshot, with results fatal to himself. Having marched all hands into the brush, the rustlers rode off.

It was not many hours before my brother Morgan, and I were on the trail. Two men had tied gunny sacks around their horses’ hoofs and ridden toward Bisbee, which was twelve miles away. The trail was a difficult one at first, but after a few miles of hard riding, the gunny sacks had worn out, and at that point, the hoof marks became quite plain. They led directly into Bisbee to the livery stable kept by Frank Stillwell and Pete Spence. Of course, we arrested the pair, and they were identified readily enough. As the mail had been robbed I could lay a federal charge against them. Stillwell and Spence were still under bond for trial when my brother Morgan was murdered. And Stillwell was the man who fired the shot. It will be recalled that Stillwell was one of a gang that waylaid me at the depot in Tucson when I was shipping Morgan’s body to California and that he was killed in the attempt. As for Pete Spence, it is only a short time ago that he was released from the penitentiary in Yuma after serving a term for killing a Mexican.

Pony Deal escaped from the scene of the stage robbery into New Mexico, where he was afterward killed while stealing cattle by the gallant Major Fountain at the head of his rangers. The story of Major Fountain’s murder is so recent that I need not repeat it.

There is such an appalling amount of killing in the preceding two paragraphs that I will turn for what stage folk call “comic relief” to a stage robber I had the pleasure of knowing slightly in former years. I met him first in Dodge City, Kansas. I always regarded him as a meritorious and not especially interesting citizen afflicted with a game knee and spoke with a brogue. Afterward, he turned up in Deadwood when I was there. There were many stage robberies around Deadwood at that time, and all the reports had for their central figure a lone road agent, tightly masked, who walked with a limp.

One shotgun messenger told me that when the coach had halted in response to a summons from behind a tree, he plucked up the courage to ask the stranger’s identity. Whereupon there came the answer, in the richest of brogues:

“It’s Lame Bradley, Knight of the Road. Throw out that box.”

The messenger still hesitated whereupon Lame Bradley shot a hole in his ear. The box was thrown down a moment later.

Lame Bradley robbed coach after coach around Deadwood, and then when suspicion was directed toward him, he returned to Dodge, where he spent money very freely. Afterward, he moved to the Panhandle in Texas, where he was killed and robbed by a chum. The chum, by the way, was duly captured and hanged.

Heigho! More killing! And who would ever have expected such garrulity from an old frontiersman? I actually astonish myself.

By Wyatt Earp in 1896, compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

Also See:

Wells Fargo – Staging & Banking in the Old West

Stagecoaches of the American West