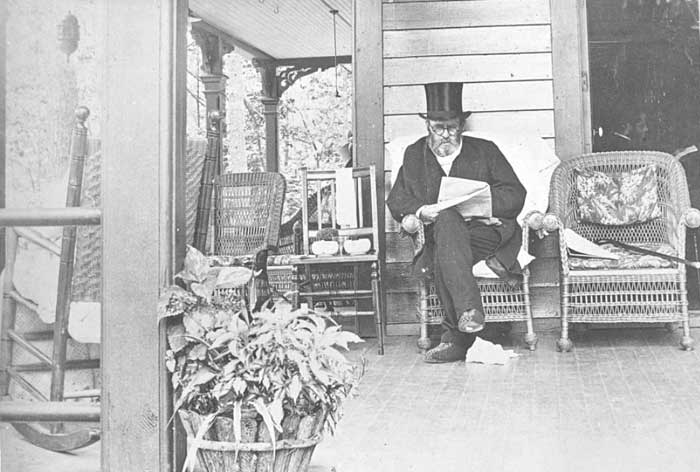

Grant reads a newspaper at his cottage in Mount McGregor, NY. This is the last known photo of the former president, taken four days before his death on July 23, 1885.

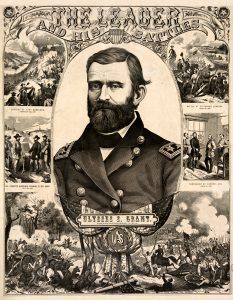

Ulysses S. Grant was a soldier, Civil War hero, politician, international statesman, and the 18th president of the United States.

Born Hiram Ulysses Grant at Point Pleasant, Ohio, on April 27, 1822, Ulysses was the oldest of six children born to Jesse and Hannah Simpson Grant.

At 17, Grant entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, graduating in 1842. Then, his name was changed to “Ulysses S. Grant” when the Congress member who appointed him to a cadetship at West Point, by accident, changed the name to U. S. Grant.

At West Point, he was said to be a “plain, common-sense, straightforward youth, shunning notoriety, and taking to his military duties in a business-like manner. He graduated in 1843, receiving an education that fitted him for his work in life.

After graduating from West Point, Grant served bravely in the Mexican-American War, winning his superior officers’ approval for distinguished bravery under fire and reaching the rank of captain.

On July 31, 1854, he resigned from the army and retired to a farm near St. Louis, Missouri. He then worked as a farmer, a real estate agent, and a bill collector before moving to Galena, Illinois. There, he worked for his father and brother in a leather shop.

When Fort Sumter, South Carolina, was fired on by the Confederates, he told a friend: “The government educated me for the army. What I am, I owe to my country. I have served her through one war and, live or die, will serve her through this.” He raised a company of volunteers and tendered his services to the Governor of Illinois, who made him adjutant-general. He rendered efficient services in this position and was then a regiment colonel on June 15, 1861. In August of the same year, he was made a brigadier-general and sent to the front, and he had several Western Theater successes. In December 1861, he was appointed the commander of the department of Cairo, Illinois. He captured Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and then Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River in Tennessee, acting in connection with the Union gunboats. Both were brilliant affairs, and Grant was made a major general.

Grant fought the great Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, on April 7, 1862, and routed the enemy in a two-day fight. On September 19, 1862, he fought and won the Battle of Iuka, Mississippi, and then besieged Vicksburg, Mississippi. This stronghold of the Confederacy surrendered to him on July 4, 1863. In November of the same year, he won a victory over General Braxton Bragg at Chattanooga, Tennessee.

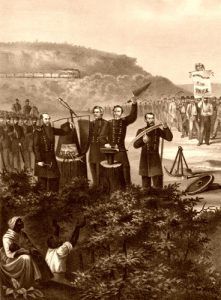

On March 1, 1864, General Grant was made lieutenant-general and commander of all United States armies. He then planned his last great campaign against General Robert E. Lee’s army in Virginia, and the Battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor followed. He besieged Petersburg and took it, and then Richmond fell into his hands. He then compelled General Robert E. Lee and his army to surrender at the Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, and the great Civil War was over.

Grant’s success and war-hero status propelled him to the White House in 1868 when he was elected as the 18th president. However, his two terms were some of the rockiest in American History. As a soldier, Grant had been superb; as a statesman, he did not fare nearly as well.

Politically inexperienced, he had problems dealing with Congress almost immediately. He was so simple, direct, and innocent himself that he failed to understand the duplicity and fraud practiced under his very nose. Like all untrained men in public positions, he made his likes and dislikes the test of his political judgments, and it was only necessary to win his friendship to have his official support. Unfortunately, his early struggle with poverty and his failure in business had led him to set too high a valuation on monetary success, making him unduly susceptible to the influence of wealthy men. He was easily managed by the astute Republican politicians in Congress, who could make the worse cause appear to him to be the better by their plausible arguments.

For example, in his treatment of the South, Grant was changed by his radical Republican associates. In a visit to the Southern states, a few months after the close of the war, he wrote that “the mass of thinking men of the South accepted in good faith” the outcome of the struggle. Yet, he constantly furnished troops to keep the carpetbag and scalawag officials in power in the South, to provide Republican votes for congressmen and presidential electors.

During these years, public morality was never so low in our country’s history, although a more honest one never sat in the White House. The country’s unsettled condition during the Civil War and the era of Reconstruction furnished an excellent opportunity for dishonesty.

Large contracts for supplies of food, clothing, ammunition, and equipment had to be filled on short notice, and men grew rich in fraudulent deeds. Our state legislatures and municipal governments fell into the hands of corrupt “rings,” and corruption reached the state’s highest offices. Secretary of War William Belknap resigned to escape impeachment for sharing the graft from the dishonest management of army posts in the West.

The President’s private secretary, Orville E. Babcock, was implicated in frauds that robbed the government of its revenue tax on whiskey. In league with corrupt post office officials, Western stagecoach lines made false returns of the amount of business done along their routes. They secured large appropriations from Congress for carrying the mail. Members of Congress went so far as to lose their sense of official propriety to accept large amounts of railroad stock as a “present” from men who wanted legislative favors for their roads.

Before Grant’s first term was over, a reform movement was started in the Republican Party to protest against corruption. The chief policies advocated were civil service reform, tariff reform, and the complete cessation of Federal military intervention in the South’s governments.

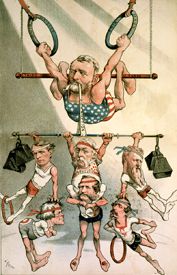

Ulysses S. Grant Corrupt Administration

Had the reform party shown the same wisdom in choosing a candidate and the management of their campaign as they did in making their platform, they might have defeated Grant in 1872. However, they chose Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, who was known as an irritable man, who had no qualifications for the office of President, and whose only real point of agreement with the reformers was a desire to see the Southern states delivered from the radical Reconstruction governments. In the meantime, Grant remained popular with the people and defeated Greeley easily.

Grant’s second term saw the nation’s gradual recovery from the political and commercial corruption of the years following the Civil War. A severe financial panic that broke in 1873 sobered the country’s businessmen and checked the wild speculation in lands and railroads that had characterized the previous five-year period.

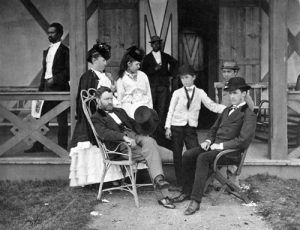

After his second term, he spent over two years on a voyage around the world with his wife before returning to his home in Galena, Illinois.

In 1879, the Republican Party’s faction sought to nominate Grant for a third term as president. Grant said little, but privately, he wanted the job and encouraged businessmen and old soldiers for their support. However, his popularity was fading, and while he received more than 300 votes in each of the 36 ballots of the 1880 convention, the nomination went to James A. Garfield.

In 1881, Grant purchased a house in New York City, and having depleted most of his savings from the trip around the world, he needed to make money. He then placed almost all his financial assets into an investment banking partnership with Ferdinand Ward. However, in 1884, Ward swindled Grant and other investors, bankrupted Grant & Ward’s company, and fled. This left Grant almost penniless, and he was forced to repay a $150,000 loan to a creditor, William H. Vanderbilt, with his Civil War mementos. Having forfeited his military pension when he assumed the office of President and destitute, Grant began a series of literary works that improved his reputation and eventually brought his family out of bankruptcy. However, he was diagnosed with throat cancer at about the same time.

Grant’s supporters in Congress rallied to get a bill passed to restore Grant to an Army General with full retirement pay. It was approved in March 1885, and he received his first pay. A few months later, and only days before his death, he finished his memoirs. The Memoirs sold over 300,000 copies, earning the Grant family over $450,000. In promoting the book, Mark Twain said it was “the most remarkable work of its kind since the Commentaries of Julius Caesar.”

Ulysses S. Grant died on July 23, 1885, at 63 and was buried in New York City’s Riverside Park.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See:

Civil War (Main Page)

General Grant and The Vicksburg Campaign

Presidents of the United States

About the Article: Parts of the preceding text were excerpted from the book An American History by David Saville Muzzey, published in 1911, and Military Heroes of the United States from Lexington to Santiago by Hartwell James, published in 1899. However, as it appears here, the text is far from verbatim, as the information has been heavily edited, truncated, and additional information added.