By Henry Eduard Legler, 1898

As Christopher Columbus’ quest for a short route to the Indies led to the discovery of a continent, so the search for a short highway to the fabled riches of China and Japan — the Cathay and Zipango of Marco Polo — brought an intrepid discoverer to the heart of that continent, Wisconsin. Here mingle the waters that, through devious channels, later flow in opposite directions — some swelling that vast volume that pours from the mighty Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico at the rate of twenty million of millions cubic feet of water annually; others passing through the chain of lakes into the St. Lawrence River, then into the frozen regions of the North Atlantic.

It was a period when the great highways of commerce were those provided by nature — the rivers and the lakes. The upper Mississippi River had not been discovered, and nothing was known of the vast continent that stretched westward. Men believed that a few days’ journey would take them to its limits — perhaps to China. When the pioneer white man steered his frail birch-bark canoe along the western shore of Green Bay, he thought he had reached China. His coming occurred in the year 1634. This was two years before Roger Williams founded his Rhode Island colony. Still, a year after the beginnings of Connecticut were made, only 27 years after the founding of the first permanent English settlement, that at Jamestown, Virginia, and but 14 years later than the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock in Massachusetts.

A Parisian mail carrier’s son was the first white man to set foot on Wisconsin soil. The year was 1634, and King Louis XIII reigned as monarch of France. Thus, by the law of nations relating to discoveries, the son of Mary de Medici became the first sovereign of Wisconsin.

Jean Nicolet entered what is now known as the Old Northwest through its natural gateway, the great arm of Lake Michigan called Green Bay. The French had sailed up the St. Lawrence River a hundred years earlier and established the first settlement in Canada. Rigorous winters and savage enmity, combined with other untoward circumstances, rendered their foothold in Montreal insecure, and exploration westward was a slow process. They had progressed no further than Lake Huron at the end of the century. No Frenchman had ventured into the forest fastnesses of Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, Indiana, or Ohio. Nothing was known about the extent of the mysterious region that stretched westward, though few men believed there was more than a narrow strip between the great lakes and the China Sea. The delusion was common that a river would be found leading to the Celestial Empire. Thus, the dream of Columbus survived in modified form 150 years after the caravel of the explorer had grated its keel on the shore of Watling’s Island.

From time to time, wandering Indians brought eager listeners in Quebec tales of the unknown western region. These made keener the desire to reach the riches of Cathay, but the vague accounts of the Indians were distorted and misapprehended. How little was known of this region is shown by a map carefully drawn by Samuel de Champlain, governor of New France, two years before Nicolet started his quest. On it, Green Bay is placed north of Lake Superior, and Lakes Huron and Ontario are connected directly. Lake Michigan is not on his map unless his Lac des Puants — the usual designation for Green Bay — is intended to represent it. An island designated as the region of copper mines, he places in Green Bay. Niagara Falls, he had never seen, and he supposed that it was rapid in the river.

Though he had mistakenly located copper mines on a Green Bay island, he knew the metal existed, for an Indian had brought him a lump of virgin ore. Other Indians, who were wont to come down the Ottawa river in their flotillas of canoes to trade with the Frenchmen, had told him of a nation dwelling some distance westward known as the “People of the Sea.” These were the Wisconsin Winnebago, who, years before, had migrated to the region of the lake that now bears their tribal name, but Champlain believed they were Chinamen.

Jean Nicolet Arrives in Wisconsin.

The fanciful description of these people given by his Indian visitors and the fact that they made their habitation on the shores of a “great water” confirmed Champlain in his belief that he had, at last, found the long-sought clue to the route to China. He chose Jean Nicolet as his ambassador. Nicolet had lived for several years among the Algonquin tribes and knew their languages. He was accustomed to the fatigues and privations of wilderness life, and the lore of the woods was a lesson he had comprehensively conned with any of his dusky companions. In July 1634, he started on his journey, accompanied by some Jesuit priests who were about to establish a mission in the Huron country and were glad to avail themselves of Nicolet’s guidance. At the Isle de Allumettes, they parted, and Nicolet pursued his way with Indian companions only. A glance at the map is necessary to convey an idea of the journey thus made in a canoe.

Starting from Quebec and leaving the St. Lawrence River at its junction with the Ottawa River, Nicolet ascended this stream to the tributary whose Indian name, Mattawin, signifies “Home of the Beaver”; then Lake Nipissing was reached utilizing a narrow passage or “carry.” Next, his canoe floated down the French River into Georgian Bay and Lake Huron. He passed the Manitoulin islands, skirted the shore of the great lake, and came to where the “People of the Falls” dwelt, the Sault Ste. Marie is familiar with modern maps. Here he and his seven Hurons rested. But a few miles westward was the eastern extremity of the largest freshwater body in the world, Lake Superior. There is no evidence that Nicolet went nearer this lake than the Sault or falls. Instead, he seems to have rested at the falls with his seven Huron companions and then retraced his way down the strait and entered Lake Michigan through the Mackinac passage. For the first time, a white man saw the broad surface of this inland sea. Along its northern shore, his canoe was paddled by his dusky oarsmen. At the bay de Noquet, he briefly tarried, and finally, he came to the Menominee, where that river pours into Green Bay.

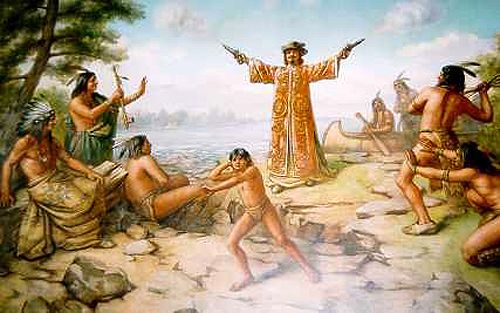

At last, Nicolet was on Wisconsin soil. He believed himself to be on the threshold of China. The Menominee, who made their habitation here, were of a lighter complexion than the Indians Nicolet knew. Some writers have ascribed this circumstance to the use of wild rice by these Indians as a staple article of diet. Champlain’s messenger learned that a short journey would bring him to the land of the Winnebago. He sent one of his Huron guides to appraise the supposed celestials of his coming and prepared to meet them in becoming style. For this purpose, he had brought a robe of gorgeous hue, like unto Joseph’s in its resplendent coloring. The early French narrative, known as the Vimont Relation, describes how Nicolet’s mandarin dress was besprinkled with birds of bright plumage and flowers of many hues in woven work.

If Nicolet erred in his conception of the Winnebago Indians, this tribe likewise formed erroneous notions concerning their visitor. They believed him a Manitou or spirit, an impression that was accentuated when he advanced into their midst with a pistol in each hand, the contents of which he discharged in the air with great dramatic effect. However, he was very disappointed to learn that the “People of the Sea,” in quest of whom he had undertaken his long and arduous canoe voyage, wore moccasins and other savage apparel in place of the product of the loom. With true French adaptability, he made the best of the situation and won French interest in these Western nations. He urged them to come to Montreal for barter and not to engage in war with the nations friendly to the French.

The coming of the remarkable man caused a great gathering of Indians. One account estimates the number of people who came to greet him at 5,000, but later accounts considerably reduced this undoubted exaggeration. A great feast was held, and judging from the number of provisions consumed, the number of warriors must have been significant, and their appetites considerably sharpened. There were consumed, if the account of the feast is valid, more than one hundred beavers, besides many deer and other forest viands secured by the chase.

When he left the Winnebago, Nicolet proceeded up the Fox River, journeying through the great regions of wild rice marshes until he came to the Mascouten tribe. He was now but a short distance from the Wisconsin River. A journey of but three days would have taken him to it, and then he could have drifted down to the “great water.” Instead, he proceeded southward towards the Illinois country, thus missing the upper Mississippi River. It was not until years later that Joliet and his party reached the Mississippi River.

After a sojourn among the Illinois and kindred tribes, Nicolet returned to the Green Bay country, doubtless along the western coast of Lake Michigan — Lac Illinois and Lac Dauphin as it appears on the early maps. He visited the Potawatomi who dwelt on the islands in the bay, and when spring thawed the ice and made canoe voyaging possible, returned to Montreal by way of the French and Ottawa Rivers.

Six months later, the great Champlain died. Indian troubles at home kept his successors from following up the investigations in the West, even if they possessed the inquiring and adventurous spirit of the “Father of New France.” Nearly a quarter of a century was to elapse before another French voyageur dared to follow in the wake of the first comer. But Nicolet had blazed the path.

The fate of Nicolet possesses a pathetic interest. A man of warm sympathies and a brave spirit, he was beloved by Frenchmen and Indians. He spent much of his time ministering to the sick and performing official duties at Three Rivers and Quebec, where he served as commissary and interpreter. One evening, word was brought to him that the Algonquin were torturing an Indian prisoner. To prevent this, he entered a launch to go to the place with several companions. A squall overturned the boat, and the occupants clung to the craft for some time. The waves tore one after another from their frail support. As Nicolet was about to be swept away, he called to his companions: “I am going to God. I commend to you, my wife and daughter.”

It was through the gateway of Wisconsin that civilization entered the Mississippi River Valley. The coming of Nicolet was but the presage of greater events. While Anglo-Saxon colonists were struggling to keep a foothold along the Atlantic coast, the volatile Frenchmen were penetrating the very heart of the continent. The former advanced slowly but kept a firm grip on everything they seized; the latter obtained their territory easily and lost it just as readily. The Anglo-Saxon built his colony on an enduring foundation; the careless, mercurial Frenchman thought but of today and had no concern for the future. As with the individual, so with the government. Had the French induced their colonists to pursue agricultural pursuits rather than encouraging them to roam the woods for beaver pelts, perhaps Wisconsin’s history would be materially different today.

The fall of New France occurred thirteen years before the minutemen at Concord and Lexington fired the signal shots of the American Revolution; long after that period, through that crucial test that cemented the colonies into a nation, through the stormy periods of the first administrations, until after the close of the war of 1812, the Wisconsin region remained essentially French. For almost 200 years, there passed in procession through Wisconsin, the French coureurs de bois, wild, lawless as the Indians with whom they fraternized; the titled and impoverished noblemen who sought glory as voyageurs; the priestly wanderers in somber garb who came with a crucifix, as their companions came with a sword.

By Henry Eduard Legler, 1898. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2025.

Source: Legler, Henry Eduard; Leading Events of Wisconsin History: The Story of the State; The Sentinel Company, Milwaukee, WI; 1898. Note: Though the context remains essentially the same, the text, as it appears here, is not verbatim.

Also See: