Samuel de Champlain, French explorer and trader

Samuel de Champlain was an explorer, navigator, map maker, soldier, French colonist, and diplomat. He made between 21 and 29 trips across the Atlantic Ocean and founded Quebec and New France on July 3, 1608. Champlain was an important figure in Canadian history who created the first accurate coastal map during his explorations and founded various colonial settlements.

Samuel de Champlain was born in La Rochelle, France, to Antoine Champlain and Marguerite Le Roy on August 13, 1567. From a family of Roman Catholic mariners, his father and uncle-in-law were sailors or navigators. He learned to navigate, draw, make nautical charts, and write practical reports at an early age. He also learned to fight with firearms and acquired practical knowledge when serving with the army of King Henry IV during the later stages of France’s religious wars in Brittany from about 1594 to 1598, beginning as a quartermaster responsible for the horses. By 1597 he was a captain serving in a garrison near Quimper.

In 1603, he went on his first voyage to Canada as a geographer on a fur-trading expedition under the guidance of his uncle, François Grave Du Pont. He explored the Saguenay, St. Lawrence, and Richelieu Rivers, collecting information to make accurate maps of Canada from Hudson Bay in the north down to the Great Lakes.

The knowledge of the New World gained on these journeys proved valuable for Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons — the man given the fur trading patent for the Acadia territory by King Henry IV of France. This vast territory ranged from modern-day Newfoundland southward to around present-day Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This lucrative monopoly over trade and land in the New World required Dugua to organize an expedition, but he was no sailor. He enlisted the help of royal cartographer and navigator Samuel de Champlain.

From 1604 to 1607, Champlain explored the Atlantic coast from the Bay of Fundy down to Cape Cod, searching for a permanent location for a French settlement. He created the first permanent European settlement north of Florida, at Port Royal, Acadia, in present-day Nova Scotia, in 1605.

On his third trip in 1608, he founded a settlement and trading post along the St. Lawrence River, which became Quebec City. It was the first permanent white settlement in Canada.

Champlain was the first European to describe the Great Lakes and published maps of his journeys and accounts of what he learned from the natives and the French.

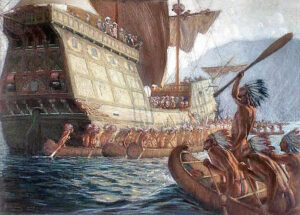

He formed long-time relationships with the Montagnai and Innu Indians and, later, with others farther west — along the Ottawa River, Lake Nipissing, and Georgian Bay, and with Algonquin and Wyandot. He agreed to assist in the Beaver Wars against the Iroquois and learned their language.

One route Champlain may have chosen to improve his access to the regent court was his decision to marry the 12-year-old Helene Boulle. She was the daughter of Nicolas Boulle, a man charged with carrying out royal decisions at court. The marriage contract was signed on December 17, 1610, in presence of Pierre Dugua, who had dealt with the father, and the couple was married three days later. The contract terms called for the marriage to be consummated two years later.

Champlain’s marriage was initially quite troubled, as Helene rallied against joining him in August 1613. While it lacked any physical connection, their relationship recovered and was apparently good for many years.

Late in 1615, Champlain returned to the Wyandot tribe and stayed with them over the winter, which permitted him to study their culture and events, which he published in a book in 1619.

In 1620, French King Louis XIII ordered Champlain to cease exploration, return to Quebec, and devote himself to the country’s administration.

Champlain’s wife Helene lived in Quebec for some time but returned to Paris and eventually decided to enter a convent. The couple had no children, and Champlain adopted three Montagnais girls named Faith, Hope, and Charity in the winter of 1627–28.

Samuel de Champlain served as Governor of New France in every way but formal title due to his non-noble status. During this time, Champlain established trading companies that sent goods, primarily fur, to France and oversaw the growth of New France in the St. Lawrence River Valley until he died in 1635.

Champlain had a severe stroke in October 1635 and died on December 25, 1635, leaving no immediate heirs. Jesuit records state he died in the care of his friend and confessor, Charles Lallemant. Although his will, drafted on November 17, 1635, gave much of his French property to his wife Helene Boulle, he made significant bequests to the Catholic missions and individuals in the colony of Quebec. However, Marie Camaret, a cousin on his mother’s side, challenged the will in Paris and had it overturned. It is unclear exactly what happened to his estate.

Samuel de Champlain was temporarily buried in the church, while a standalone chapel was built to hold his remains in the upper part of the city. Unfortunately, this small building and many others were destroyed by a large fire in 1640. Though immediately rebuilt, no traces of it exist, and his exact burial site is still unknown, despite much research. However, there is general agreement that the previous Champlain chapel site, and the remains of Champlain, are somewhere near the Notre Dame de Quebec Cathedral.

By the time of Champlain’s death, almost 300 French pioneers were living in New France.

Champlain is honored throughout Canada. Many places bear his name, including Lake Champlain. But his legacy is best seen in the city of Quebec.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Sources:

Find a Grave

Mariners’ Museum & Park

National Park Service

Wikipedia