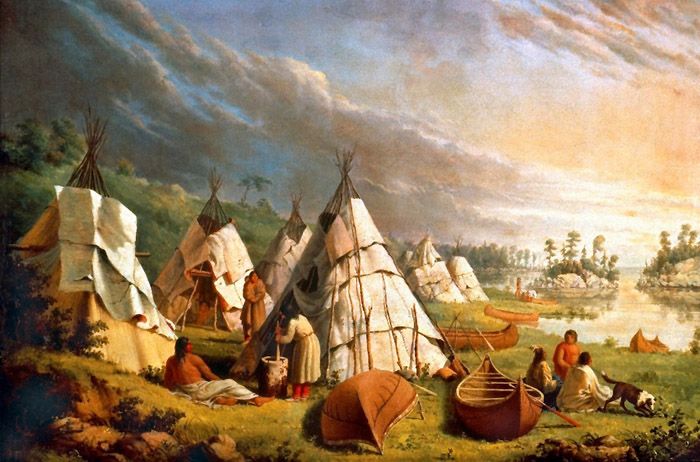

The Potawatomi are an Algonquian Native American people of the Great Plains, upper Mississippi River, and western Great Lakes region. Their name is a translation of the Ojibwe word “potawatomink,” meaning “people of the place of fire.” In their language, the Potawatomi refer to themselves as the Nishnabek or “people.”

The Potawatomi were part of a long-term alliance called the Council of Three Fires with the Ojibwe and Ottawa, who shared or had similar language, manners, and customs. Early on, they were estimated to have numbered about 8,000 people.

Their first European contact occurred in 1634 when Jean Nicolet arrived at Green Bay, Wisconsin, and met a few Potawatomi there. However, the tribe lived in Michigan then, so they were probably visiting. Then, in the 1640s, the Iroquois Confederacy of New York began to raid Indian tribes throughout the Great Lakes region to monopolize the regional fur trade. Forced westward, the Potawatomi then settled on the Door County Peninsula in Wisconsin. After 30 years of war, relocation, and disease epidemics, the French estimated about 4,000 Potawatomi in 1667.

As the Algonquin tribes began driving the Iroquois back to New York, the Potawatomi moved south to the southern end of Lake Michigan. In 1701, the French built Fort Ponchartrain at Detroit, and groups of Potawatomi settled nearby. By 1716, most Potawatomi villages were located between present-day Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Detroit, Michigan.

The Potawatomi became trading partners and military allies of the French. When the Fox Indians rose up in Wisconsin against the French between 1712 and 1735, the Potawatomi participated in many battles on the French side. They later assisted the French in their wars with the Chickasaw and the Illinois tribes. During the 1760s, they expanded into northern Indiana and central Illinois.

When the French and English began to battle each other over control of North American lands, the tribe fought in a series of wars with the French, including King George’s War in 1746-47 and the French and Indian War from 1754 to 1763. With England’s victory in this war, all French possessions in Canada and the Midwest reverted to British control. Wary of their new colonial overlords, they participated in Ottawa Chief Pontiac’s Rebellion against the British in 1863. The British put down the rebellion in 1866 and afterward established better diplomatic and economic relations with the tribes to prevent such recurrences.

During the American Revolution, most Potawatomi in Illinois remained neutral or even favored the Americans, but their kinsmen in Michigan were more pro-British. The Revolutionary War “officially” ended in 1783 with the Treaty of Paris, which placed the western boundary of the United States at the Mississippi River.

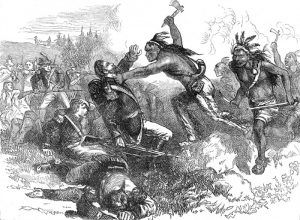

The U.S. government then tried to establish a boundary with the Ohio tribes through treaties, but frontiersmen ignored them and moved onto native lands. This resulted in a bloody war between the United States and the Ohio Indians, supported by the British, from 1790 to 1794, in which the Potawatomi from Michigan and Indiana participated. The war continued until the Indians were put down by “Mad Anthony” Wayne at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. In November, the British signed the Jay Treaty, resolving their differences with the United States, and agreed to leave their forts on American territory. The alliance chiefs signed a treaty ceding most of Ohio, including 240 Potawatomi members. Although the Potawatomi did not surrender any of their lands, they received $1,000 for signing. Afterward, more than 60 of the Potawatomi leaders, who had attended the treaty negotiations at Greenville, Ohio, mysteriously got sick and died. The British claimed Americans had poisoned them.

The native tribes signed several treaties in the next few years, but it wasn’t until the Detroit Treaty was signed in November 1807 that the Potawatomi were required to surrender some of their lands. By this time, the Potawatomi tribal lands included northern Illinois, southeastern Wisconsin, northern Indiana, southern Michigan, and northwestern Ohio.

Afterward, many Potawatomi became followers of Tenskawatawa, the Shawnee Prophet, and his brother Tecumseh, who preached a doctrine of resisting American expansion onto Indian lands. The brothers assembled an Indian military alliance that included the Potawatomi, who fought on the British side during the War of 1812. Once the war started, the Potawatomi defeated the American garrison at Fort Dearborn in Chicago. When the war ended in 1814, the British gave up the lands in Wisconsin and other parts of the Midwest.

Afterward, the Potawatomi fell on hard times and often could not hunt and grow enough food to eat. Soon, they had little choice except to cede their land to the United States in exchange for money to survive. Several treaties and land cessions were made in the next several years, and the Potawatomi west of the Mississippi River were removed between 1834 and 1842.

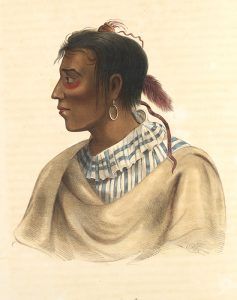

The Potawatomi were removed in two groups, with the Prairie and Forest Bands from Illinois and Wisconsin moved to Council Bluffs in southwest Iowa, and the Potawatomi of the Woods, which included the Michigan and Indiana bands, relocated to eastern Kansas near Osawatomie. One band of Potawatomi, led by Chief Menominee, refused to leave their homelands at their Twin Lakes village in Indiana. Menominee was soon joined by hundreds of other Potawatomi who did not want to leave, and over time, Menominee’s band grew from four wigwams to more than a hundred. However, in August 1838, soldiers forced them to begin a march to Kansas, now known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death. During the forced removal, 42 of the 859 Potawatomi died.

In 1846, the Iowa and Kansas groups merged and were placed on a single reservation north of Topeka, Kansas. This group separated in 1867, with the Citizen Potawatomi moving to Oklahoma near present-day Shawnee.

During these years of removal, the tribe fractured, and many members avoided removal and remained in the Great Lakes area. Others went with the Kickapoo to Texas and Kansas, and some migrated to Canada. About 200 of the Potawatomi who went to Iowa and Kansas returned to Wisconsin and settled near Wisconsin Rapids.

Today, several federally recognized bands of Potawatomi are in the United States and Canada.

United States:

Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Shawnee, Oklahoma

Forest County Potawatomi Community, Wisconsin

Hannahville Indian Community, Michigan

Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi, also known as the Gun Lake Tribe, Dorr, Michigan

Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi, Calhoun County, Michigan;

Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, Michigan and Indiana

Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation, Mayetta, Kansas.

Canada:

Caldwell First Nation, Point Pelee and Pelee Island, Ontario

Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation, Bruce Peninsula, Ontario

Saugeen First Nation, Ontario

Chippewa of Kettle and Stony Point, Ontario

Moose Deer Point First Nation, Ontario

Walpole Island First Nation, on an unceded island between the United States and Canada

Wasauksing First Nation, Parry Island, Ontario

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Native American Photo Galleries

Sources:

Potawatomi History

Wikipedia

Wisconsin Natural History Museum