The Illinois Confederation, also called the Illiniwek or Illini, was a group of 12–13 Native American tribes who lived in the Mississippi River Valley, occupying an area from Lake Michigan to Iowa, Illinois, and south to Missouri and Arkansas. The five main tribes were the Cahokia, Kaskaskia, Michigamea, Peoria, and Tamaroa. They called themselves “Hileni” or “Illiniwek,” meaning “men,” which the French rendered as “Illinois.”

Most of the Illinois spoke various dialects of the Miami-Illinois language, one of the Algonquian languages family, except for the Siouan-speaking Michigamea.

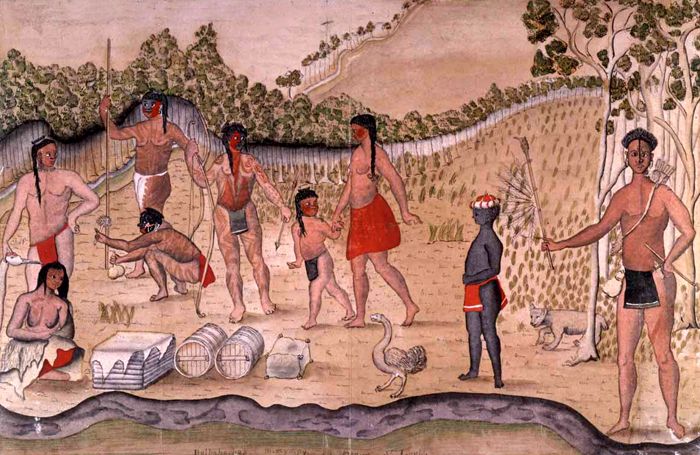

The Illinois lived in a seasonal cycle of cultivating domestic crops, hunting, and fishing, with movement from semi-permanent villages to hunting camps. They seasonally lived in longhouses and wigwams of wood and woven mats. They planted corn, beans, pumpkins, and squash crops and gathered wild foods such as nuts, fruit, and roots. They also tapped maple trees and made the sap into a drink or boiled it for syrup and sugar.

The main activities of the men were hunting and warfare, while the women worked in the fields, prepared and preserved the food, turned the hides into equipment and clothing, and did most of the work around the camp and village. The Illinois practiced polygamy, and wives suspected of unfaithfulness were severely punished, sometimes suffering the loss of an ear or nose. A few of the men dressed and acted out the social role of women. The tribe called these men Ikoneta, but the French called them Berdache. Small boys who showed marked tendencies toward femininity were raised as girls.

When French explorers first journeyed to the region from Canada in the 17th century, they numbered over 10,000 people. Before this time, they had been even larger but had declined due to several costly wars with the Iroquois and Sioux tribes. Their numbers were further reduced after Europeans arrived, and they were exposed to infectious diseases to which they had no natural immunity.

In about 1640, French explorers and missionaries expanded their field of operations from the St. Lawrence River into the Great Lakes region. The French were intrigued by vague reports of a large tribe that lived seven days’ journey west of Lake Michigan, but it was not until 1666 that they made contact with the Illinois. This meeting occurred when about 80 Illinois Indians traveled northward on a trading expedition to Chequamegon Bay on the southwestern shore of Lake Superior.

After the Illinois traders made additional trips to Lake Superior during the next few years, missionaries admired their calm disposition and viewed them as good candidates for conversion to Christianity. Father Jacques Marquette longed to establish a mission among the Illinois and began to study their language and culture. Marquette finally got an opportunity to visit the Illinois in 1673 when he accompanied Louis Jolliet on an expedition to explore the Mississippi River.

The Illinois had several traditional enemies, including the Sioux, Osage, Pawnee, and Arikara to the west and the Quapaw to the south. Beginning in the 1650s, they also came under attack from Iroquois war parties from the east who had hunted out their traditional lands and sought more productive hunting and trapping areas.

In 1680, the Iroquois killed or captured more than 700 Tamaroa near the mouth of the Illinois River. The threat of Iroquois raids subsided in the early 1700s, but new hostilities emerged with northern tribes like the Sauk & Fox, Kickapoo, Sioux, and Potawatomi. Pressure also came from southern tribes, including the Quapaw, Shawnee, and Chickasaw. Some conflicts were inspired not by the tribes themselves but by French, British, and American forces that enlisted Indian warriors as allies.

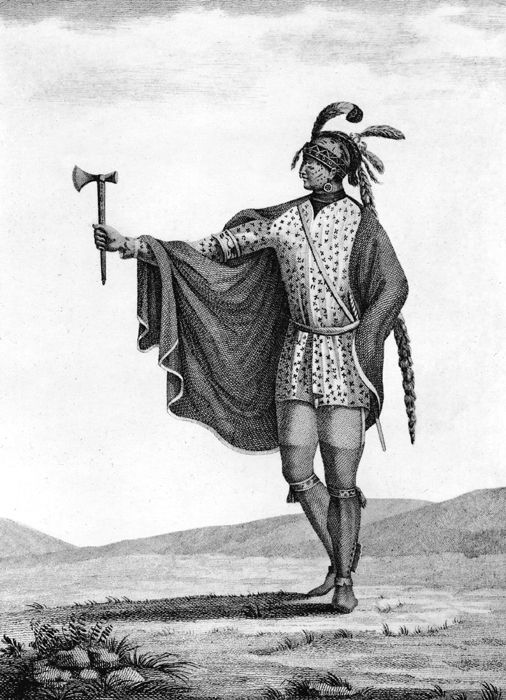

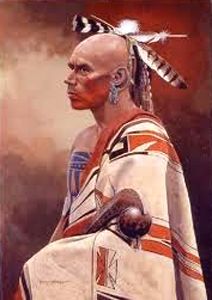

Illini Warrior

By 1778, their numbers had dramatically declined due to war and diseases. As a result, many of the Illinois people migrated to present-day eastern Kansas.

By 1832, they had been reduced to a village of fewer than 300 people in the State of Illinois. They then ceded the last of their Illinois lands and settled on a reservation in eastern Kansas. They merged with the Wea and Piankashaw tribes in 1854 and became the Confederated Peoria Tribe.

In 1867, they left Kansas and moved to a new reservation in northeast Oklahoma. Several years later, they were joined on the reservation by members of the Miami Tribe. The Confederated Peoria officially merged with the Miami in 1873, forming the United Peoria and Miami Tribe. This union dissolved in the 1920s. In 1959, the US government dissolved the Peoria tribal government, but the tribal members began regaining federal recognition, which they achieved in 1978.

Today, many descendants of the Illinois Confederacy and the Piankeshaw, Kaskaskia, and Wea are enrolled in the Peoria Tribe of Miami, Oklahoma.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See:

Native American Photo Galleries

Native Americans – First Owners of America

Sources: