Fort Sumter, South Carolina, is best known as the site where the shots that initiated the American Civil War were fired. The fort was built after the War of 1812 as part of a series of fortifications along the southern U.S. coast and was named for General Thomas Sumter, a Revolutionary War hero. The building began in 1829 when 70,000 tons of granite were imported from New England to build a sandbar at the entrance to Charleston harbor, which the site dominates.

The fort is a five-sided brick structure with walls about 180 feet long, five feet thick, and 50 feet tall. It was designed to house 650 men and 135 guns across three tiers of gun emplacements, although it was never filled to its full capacity. As with many Federal projects, enslaved laborers and craftsmen were among the men who worked on this structure.

The fort was still unfinished when Major Robert Anderson moved his 85-man garrison into it on December 26, 1860, setting in motion events that would tear the nation asunder four months later.

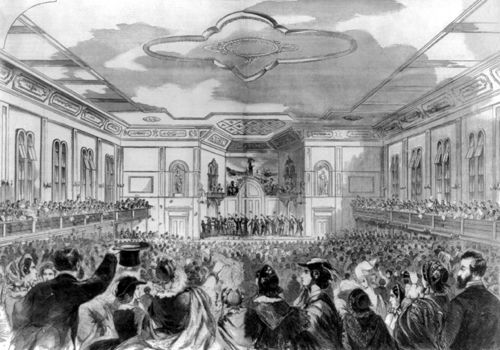

South Carolina Legislature discussing secession in Charleston.

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina delegates to a special secession convention voted unanimously to secede from the Federal Union. In November, Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the United States without support from the southern states. The critical significance of this election was expressed in South Carolina’s Declaration of the Immediate Causes of Secession: “A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery.” The Declaration claimed that secession was justified because the Federal Government had violated the Constitutional compact by infringing upon the rights of the sovereign states.

As the primary violation, the Declaration listed the failure of northern states to enforce the Federal Fugitive Slave Act or to restrict the actions of antislavery organizations. “Thus the constituted compact [the U.S. Constitution] has been deliberately broken and disregarded by the non-slaveholding States, and the consequence follows that South Carolina is released from her obligation.” The Declaration expressed South Carolina’s fear that “The slaveholding States will no longer have the power of self-government, or self-protection, and the Federal Government will have become their enemy.”

As the country expanded, the regional conflict centered on extending slavery into new American territories. Included in the arguments was the fate of enslaved African Americans fleeing from the South. Over the decades, the North and South tried and failed to reach agreements on geographic boundaries for slavery, the recapture of runaways, and the status of free blacks throughout the nation. National political parties, religious denominations, and families were divided over these issues.

In the months between Lincoln’s election and his inauguration, as more southern states proclaimed secession, efforts at compromise continued. Southern Unionists and their northern supporters believed that the Union could be restored without war if only the southern states guaranteed that the Federal Government would not interfere with their slave property. A Constitutional amendment guaranteeing the rights of slave owners was suggested. Still, Lincoln concluded that no compromise plan would ever fully satisfy South Carolina, the state that led the South in defense of the rights of slaveholders and the right of secession.

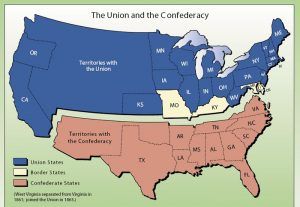

Within six weeks of South Carolina’s secession, five other states followed suit: Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana. Early in February 1861, delegates met in Montgomery, Alabama, adopted a constitution, established a provisional government—the Confederate States of America—and elected Jefferson Davis as their president. By March 2, when Texas officially joined the Confederacy, nearly all the Federal forts and navy yards in the seven seceding states had been seized by the new government. Fort Sumter was one of the few that remained in Federal hands.

When South Carolina seceded, there were four Federal installations around Charleston Harbor: Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island, Castle Pinckney on Shute’s Folly Island near the city, Fort Johnson on James Island across from Moultrie, and Fort Sumter at the harbor entrance.

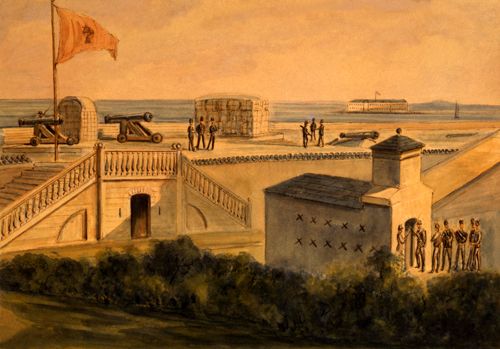

Fort Moultrie, South Carolina.

Fort Moultrie was the only post garrisoned by more than a nominal number of soldiers, where Major Robert Anderson commanded two companies, 85 men, of the First U.S. Artillery. Six days after South Carolina seceded, Anderson concluded that Moultrie was indefensible and secretly transferred his command to Fort Sumter, a mile away. On December 27, South Carolina volunteers occupied Fort Moultrie, Fort Johnson, and Castle Pinckney and erected batteries around the harbor.

South Carolina regarded Anderson’s move as a breach of faith and demanded that the U.S. Government evacuate Charleston Harbor. President James Buchanan refused, and in January 1861, attempted a relief expedition. South Carolina shore batteries, however, turned back the unarmed merchant vessel, Star of the West, carrying 200 men and several months’ provisions as it tried to enter the harbor.

Early in March, Brigadier General Pierre G.T. Beauregard took command of the Confederate troops at Charleston and pushed work on fortifying the harbor. As the weeks passed, Fort Sumter gradually became the focal point of tensions between North and South.

When Abraham Lincoln assumed the office of President on March 4, 1861, he vowed, in a firm yet conciliatory address, to uphold national authority. The Government, he said, would not assail anyone, but neither would it consent to a division of the Union. “The power confided to me will be used to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the Government.”

By April 4, Lincoln believed that a relief expedition was feasible and ordered merchant steamers, protected by ships of war, to carry “subsistence and other supplies” to Major Robert Anderson. He also notified South Carolina Governor Francis W. Pickens that an attempt would be made to resupply the fort.

After considerable debate and some disagreement, the Confederate Secretary of War telegraphed Beauregard on April 10 that if he were certain Sumter was to be supplied by force, “you will at once demand its evacuation, and if this is refused, proceed, in such manner as you may determine, to reduce it.”

On April 11, Confederate General Beauregard demanded that Anderson surrender Fort Sumter. Anderson refused. At 3:20 a.m., April 12, the Confederates informed Anderson that their batteries would open fire in one hour. At ten minutes past the allotted hour, Captain George S. James, commanding Fort Johnson’s east mortar battery, ordered the firing of a signal shell. Within moments, Edmund Ruffin of Virginia, firebrand and hero of the secessionist movement, touched off a gun in the ironclad battery at Cummings Point. By daybreak, Forts Johnson and Moultrie batteries, Cummings Point, and elsewhere were assailing Fort Sumter.

Major Anderson withheld his fire until 7 o’clock. Though some 60 guns stood ready for action, most never got into the fight. Nine or ten casemate guns returned fire, but only six remained in action by noon. At no time during the battle did the guns of Fort Sumter greatly damage Confederate positions. The cannonade continued throughout the night. The next morning, a hotshot from Fort Moultrie set fire to the officers’ quarters. In the early afternoon, the flagstaff was shot away. At about 2 p.m., Anderson agreed to a truce. That evening, he surrendered his garrison. Miraculously, no one on either side had been killed during the engagement, but five Federal soldiers suffered injuries.

On Sunday, April 14, Major Anderson and his garrison marched out of the fort and boarded the ship for transport to New York. They had defended Sumter for 34 hours until “the quarters were entirely burned, the main gates destroyed by fire, the gorge walls seriously injured, the magazines surrounded by flames.” The Civil War had officially begun.

With Fort Sumter in Confederate hands, the port of Charleston became an irritating loophole in the Federal naval blockade of the Atlantic Coast. In 1863, 21 Confederate vessels cleared Charleston Harbor in two months, and 15 entered. Into Charleston came needed war supplies; out went cotton in payment.

To close the port and capture the city, Fort Sumter, which had been repaired and armed with some 95 guns, needed to be seized first. After an earlier Army attempt on James Island failed, the job fell to the U.S. Navy, and Rear Admiral Samuel F. Du Pont was ordered to take the fort.

On the afternoon of April 7, 1863, nine armored vessels steamed slowly into the harbor and headed for Fort Sumter. For 2 ½ hours, the ironclads dueled with Confederate batteries in the forts and around the harbor. The naval attack only scarred and battered Sumter’s walls, but the far more intense and accurate Confederate fire disabled five Federal ships, one of which, the Keokuk, sank the next morning.

When the ironclads failed, the Federal strategy changed. Du Pont was removed from command and replaced by Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, who planned to combine land and sea operations to seize nearby Morris Island and, from there, demolish Fort Sumter. Union troops under Major General Quincy A. Gillmore began to place rifled cannons powerful enough to breach Sumter’s walls at a position secured by U.S. forces on Morris Island.

Meanwhile, Confederate laborers and slaves inside Fort Sumter worked day and night with bales of cotton and sand to buttress the walls facing the Federal guns. The fort’s garrison at this time consisted of five First South Carolina Artillery companies under Colonel Alfred Rhett. Federal troops fired a few experimental rounds at the fort in late July and early August. The bombardment began on August 17, with almost 1,000 shells being fired on the first day alone. Within a week, the fort’s brick walls were shattered and reduced to rubble, but the garrison refused to surrender and continued repairing and strengthening the defenses.

Confederate guns at Fort Moultrie and other points now defended Sumter. Another Federal assault on September 9 fell short; this time, the attackers lost five boats and 124 men trying to take the fort from Major Stephen Elliott and fresh Confederate troops under his command. Except for one ten-day period of heavy firing, the bombardment continued intermittently until the end of December. By then, Sumter’s cannons were severely damaged and dismounted, and its defenders could respond with only “harmless musketry.”

In the summer of 1864, Major General John G. Foster replaced Gillmore as commander of land operations, and the Federals made one last attempt to take Fort Sumter. Foster, a member of Anderson’s 1861 garrison, believed that “with proper arrangements,” the fort could be taken “at any time.” However, a sustained two-month Union bombardment failed to dislodge the 300-man Confederate garrison. Foster was ordered to send most of his remaining ammunition and several regiments of troops north to aid Grant’s overland campaign against Richmond.

Desultory fire against the fort continued through January 1865. For 20 months, Fort Sumter had withstood Federal siege and bombardment, and it no longer resembled a fort at all. But, defensively, it was more vital than ever. Big Federal guns had hurled seven million pounds of metal at it, yet the Confederate losses during this period had been only 52 killed and 267 wounded.

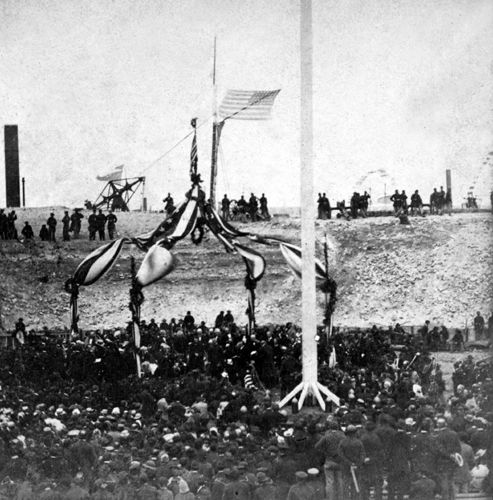

The Confederacy never surrendered Fort Sumter, but General William T. Sherman’s advance through South Carolina finally forced the Confederates to evacuate Charleston on February 17, 1865, and abandon Fort Sumter. With a flag-raising ceremony, the Federal government formally took possession of Fort Sumter on February 22, 1865.

Victory Celebration at Fort Sumter, 1865.

When the Civil War ended, Fort Sumter presented a very desolate appearance. None of the original walls could be seen on the left flank, left face, or right face. The right flank and the gorge walls, which had taken the brunt of the Federal bombardments, were now irregular mounds of earth, sand, and debris forming steep slopes down to the water’s edge. The fort bore little resemblance to the impressive work that had stood there when the war began in 1861.

The Army attempted to restore Fort Sumter to military readiness during the decade following the war. The horizontal irregularity of the damaged or destroyed walls was given some semblance of uniformity by leveling jagged portions and rebuilding others. A new sally port was cut through the left flank; storage magazines and cisterns were constructed, and gun emplacements were located. Eleven original first-tier gunrooms at the salient and along the right face were reclaimed and armed with 100-pounder Parrott guns.

From 1876 to 1897, Fort Sumter was not garrisoned and served mainly as a lighthouse station. During this period, maintenance of the area was so poor that the gun platforms rotted, the guns rusted, and the area eroded. The impending Spanish-American War, however, prompted renewed activity that resulted in the construction of Battery Huger in 1898 and the installation of two long-range 12-inch rifles the following year.

Fortunately, the war ended quickly, and the guns were never fired in anger. During World War I, a small garrison manned the rifles at Battery Huger. However, although the Army maintained the fort for the next 20 years, it was not used as a military establishment. It became a tourist destination until World War II brought about the fort’s reactivation. The Battery Huger rifles, long since outmoded, were removed in about 1943.

During late World War II, 90-mm anti-aircraft guns were installed along the fort’s right flank and manned by a Coast Artillery company. Fort Sumter became a national monument in 1948 when it was transferred from the War Department to the National Park Service.

The Fort Sumter Visitor Education Center, located at 340 Concord Street in Charleston, provides extensive exhibits that tell the story of growing sectionalism and strife between the North and the South and how these problems ultimately erupted into the Civil War at Fort Sumter. The museum also tells the story of the construction of the fort and island, the events leading to the April 12-13, 1861, battle, and the subsequent bombardment and reduction of Fort Sumter by artillery later in the war.

Fort Sumter National Monument is located in Charleston Harbor and can be reached only by boat. Between April 1 and Labor Day, the fort is open from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.; the hours vary at other times of the year.

Tour boats operated by a National Park Service concessionaire leave from the Fort Sumter Tour Boat Facility at Liberty Square in downtown Charleston. Liberty Square is located on the Cooper River at the eastern end of Calhoun Street.

Though the Fort Sumter of today bears only a superficial resemblance to its original appearance, there is still much history to see and experience. Battery Huger, built across the parade ground during the Spanish-American War, dominates the interior. A walking tour also provides views of the Sally Port, built in the 1870s, the ruins of the officers’ quarters, enlisted men’s barracks, gunrooms, and more.

More Information:

Fort Sumter National Monument

1214 Middle Street

Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina 29482

843-883-3123

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2025.

Also See:

Source: Fort Sumter National Monument