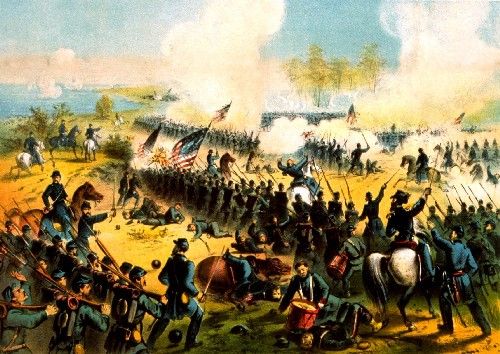

Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, from 3-D display at the Shiloh Visitor’s Center, photo by Kathy Alexander

“No soldier who took part in the two day’s engagement at Shiloh ever spoiled for a fight again. We wanted a square, stand-up fight and got all we wanted of it.” — Union Veteran

The Shiloh National Military Park, established on December 27, 1894, preserves the site of the bloody Battle of Shiloh in April 1862 and the siege, battle, and occupation of the key railroad junction at nearby Corinth, Mississippi. The park also includes the Shiloh National Cemetery, which contains around 4,000 soldiers and their family members, and the Shiloh Indian Mounds, a National Historic Landmark in its own right.

Battle of Shiloh (April 6-7, 1862) – Also called the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, this battle took place in Hardin County, Tennessee.

By mid-February 1862, Union forces had won decisive victories in the West at Mill Springs, Kentucky, and Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee. These successes opened the way for invasion up the Tennessee River to sever Confederate rail communications along the important Memphis & Charleston and Mobile & Ohio railroads. Forced to abandon Kentucky and Middle Tennessee, General Albert Sidney Johnston, supreme Confederate commander in the West, moved to protect his rail communications by concentrating his scattered forces around the small town of Corinth in northeast Mississippi where the strategic crossroads of the Memphis & Charleston and the Mobile & Ohio Railroads sat.

In March, Major General Henry W. Halleck, commanding U.S. forces in the West, advanced armies under Major Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Don Carlos Buell southward to sever the Southern railroads. Grant ascended the Tennessee River by steamboat, disembarking his Army of Tennessee at Pittsburg Landing, 22 miles northeast of Corinth. There, he established a base of operations on a plateau west of the river, with his forward camps posted two miles inland around a log church called Shiloh Meeting House. Halleck had specifically instructed Grant not to engage the Confederates until he had been reinforced by Buell’s Army of Ohio, then marching overland from Nashville. Once combined, the two armies would advance on Corinth and permanently break western Confederate railroad communications.

General Johnston, aware of the Federal designs on Corinth, planned to smash Grant’s army at Pittsburg Landing before Buell arrived. He placed his troops in motion on April 3, 1862, but heavy rain and difficulties encountered by marching large columns of men, artillery, and heavy wagons over muddy roads, delayed the attack. By nightfall on April 5th, his Army of Mississippi, nearly 44,000 men present for duty, was finally deployed for battle four miles southwest of Pittsburg Landing.

At daybreak, on Sunday, April 6th, the Confederates stormed out of the woods and assailed the forward Federal camps around Shiloh Church. Grant and his nearly 40,000 men present for duty were surprised by the onslaught. The Federals soon rallied, however, and bitter fighting consumed “Shiloh Hill.” Confederate brigades slowly gained ground throughout the morning, forcing Grant’s troops to give way, grudgingly, to fight a succession of defensive stands at Shiloh Church, the Peach Orchard, Water Oaks Pond, and within an impenetrable oak thicket that battle survivors named the Hornets’ Nest.

Despite having achieved surprise, Johnston’s troops soon became as disorganized as the Federals. The Southern attack lost coordination as corps, divisions, and brigades became entangled. Then, as he supervised an assault on the Union left in mid-afternoon, Johnston was struck in the right leg by a stray bullet and bled to death, leaving General P.G.T Beauregard in command of the Confederate army. Grant’s battered divisions retired to a strong position extending west from Pittsburg Landing, where massed artillery and rugged ravines protected their front and flanks. The fighting ended at nightfall.

Overnight, reinforcements from Buell’s Union army reached Pittsburg Landing. Beauregard, unaware Buell had arrived, planned to finish the destruction of Grant the next day. At dawn on April 7th, however, it was Grant who attacked. The combined Union armies, numbering over 54,500 men, hammered Beauregard’s depleted ranks throughout the day, now mustering barely 34,000 troops. Despite mounting desperate counterattacks, the exhausted Confederates could not stem the increasingly stronger Federal tide. Forced back to Shiloh Church, Beauregard skillfully withdrew his outnumbered command and returned to Corinth. The battered Federals did not press the pursuit.

The Battle of Shiloh, or Pittsburg Landing, was over. It had cost both sides a combined total of 23,746 men killed, wounded, or missing — more casualties than America had suffered in all previous wars — and ultimate control of Corinth’s railroad junction remained in doubt.

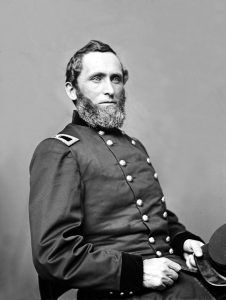

Major General Henry W. Halleck, recognizing Corinth’s military value, considered its capture more important than the Confederate armies’ destruction. Reinforced by another army under General John Pope, he cautiously advanced southward from Tennessee. By late May, he entrenched his three armies within cannon range of Confederate fortifications defending the strategic crossroads. Despite being reinforced by Major General Earl Van Dorn’s Trans-Mississippi Army, Beauregard withdrew south to Tupelo, Mississippi, abandoning the most viable line of east-west rail communications in the western Confederacy.

Federal efforts to recover the Mississippi Valley stalled in the late summer of 1862 and Confederate leaders launched counteroffensives in every theater. Armies led by Generals Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith invaded Kentucky, while troops under General Van Dorn boldly attacked the heavily fortified Union garrison at Corinth, “linchpin” of Federal control in northern Mississippi. In one of the more bitterly contested battles of the war, Van Dorn was decisively repulsed, following two days of carnage on October 3-4, 1862 that claimed nearly 7,000 more Confederate and Union casualties.

Although overshadowed by the failure of Robert E. Lee’s Confederate invasion in Maryland, Van Dorn’s defeat, coupled with Bragg’s retreat from Kentucky after the Battle of Perryville on October 8, 1862, caused discouragement in Richmond, Virginia and relief in Washington. More significantly, Van Dorn’s defeat at Corinth — the last Confederate offensive in Mississippi — seriously weakened the only mobile Southern army defending the Mississippi Valley. This permitted Major General Ulysses S. Grant to launch a relentless nine-month campaign to capture “the fortress city” of Vicksburg and recover the Mississippi River.

Hornets’ Nest

Of the many separate skirmishes within the greater Battle of Shiloh, the best known is that of the Hornet’s Nest. Ranking with Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, Bloody Lane at Antietam, and the Stone Wall at Fredericksburg, Shiloh’s Hornet’s Nest is well known to even the most amateur of Civil War buffs.

Lying in the center of Shiloh Battlefield, this was the heavy combat scene on both days of the battle. On the first day, three Union divisions manned the line along a little-used farm road that ran through the J.R. Duncan land. Duncan and his family worked a small cotton field that bordered the road to the south. With its open fields of fire and road cover, there is little wonder that the Duncan plot became one of the most important localities on the battlefield. Heavy fighting raged in the Hornet’s Nest area on the first day, with no less than eight distinct Confederate attacks turned back by the determined defenders. Confederates named the location because, they said, the enemy’s bullets sounded like swarms of angry hornets.

After having witnessed the unsuccessful attacks against the position, Confederate General Daniel Ruggles formed a line of artillery consisting of as many as 62 guns and concentrated its fire upon the Federal line. With the aid of these cannons, the Confederates were able to form a circle around the Hornet’s Nest, surrounding and capturing General Prentiss, with more than 2,200 troops, late in the day on April 6th.

Almost as soon as the battle ended, key participants began describing the Hornet’s Nest’s action as the central event of the battle. Defenders of the area, such as Brigadier General Benjamin Prentiss, openly argued that their stand made against so many brave Confederate attacks held the Union line long enough for army commander General Ulysses S. Grant to establish a last line of defense. Over the years, historians expanded on the veteran’s remembrances and, even today, continue to argue the importance of the Hornet’s Nest. In portraying the Hornet’s Nest as the savior of Grant’s army, historians made it an American icon.

However, historians today believe that a different story probably took place and question the overall importance of the Hornet’s Nest’s role in the battle.

Several pieces of evidence offer insight into the context of the battle as a whole. The number of dead and wounded in the area shows that the Hornet’s Nest did not see Shiloh’s heaviest fighting. An 1867 document, produced by laborers locating bodies on the battlefield, states that the heaviest concentrations of dead lay on the eastern and western sectors of the battlefield and that the dead were fairly light in the center, where the Hornet’s Nest was located. In itself, that states that casualties were fewer in the center where, according to early writings, the heaviest and most important fighting took place.

Supporting this point are casualty figures for the units engaged in the Hornet’s Nest. Colonel James M. Tuttle’s brigade of four Iowa regiments, which held the Hornet’s Nest and the road in front of Duncan Field, sustained 235 killed and wounded in the battle – a number less than some individual regiments sustained on other parts of the field. Troop positions also show that the Hornet’s Nest was not a critical area on the field for most of the day. When they went into action, Colonel Thomas W. Sweeny’s Union brigade of six regiments, positioned in Duncan Field, north of the Corinth Road, did not have ample room to deploy. As a result, only two regiments went online while Sweeny held the other four in reserve.

Once the Union line began to fall apart on either side of the Hornet’s Nest, Sweeny began to send his reserve regiments as reinforcements for the other more critical areas. He sent two Illinois regiments to the Peach Orchard sector and one to the north to aid Major General John A. McClernand. Only one regiment went to aid the Hornet’s Nest. Had the Hornet’s Nest been a critical point with desperate and severe fighting, Sweeny probably would not have sent his regiments away from the area. Furthermore, troop position tablets show that very little action took place in Duncan Field. Knowing what would happen to charges across open ground, Confederate officers chose to seek cover while making their attacks. Duncan Field, where a myth states that so many Confederate charges took place, has no Confederate tablets denoting troop positions.

If the Hornets’ Nest was not the central event in the Battle of Shiloh, why then did it become so important to historians? The answer is simple. For years after the Civil War, veterans of the Hornet’s Nest emphasized their role in the battle, claiming that their sacrifice had provided Grant with enough time to establish a last line of defense. Division commander Brigadier General Benjamin M. Prentiss wrote a widely circulated report after the battle, which emphasized his role in the battle and that of his troops. Even after the war, veterans still claimed the Hornet’s Nest’s defense was the central event of Shiloh.

The new interpretations of Hornets’ Nest do not minimize the fighting role in the center of the battlefield. The area was indeed important, especially later when almost every Confederate unit on the battlefield concentrated at that point. Many Confederate charges swept forward into the grueling Federal fire, only to be turned away. Hundreds of brave men and boys lost their lives in the Hornet’s Nest. For all these reasons, the Hornets Nest continues to be very important; however, perhaps not as important as other, less well-known operations taking place simultaneously on other parts of the battlefield.

After the Battle of Shiloh, Union troops would continue into Corinth, Mississippi, where opposing forces would battle between April 29-June 10, 1862 in the Siege of Corinth. When General P.G.T Beauregard evacuated the town, the Union had consolidated their position, ending the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers Campaign.

The Union victory at the bloody Battle of Shiloh resulted in estimated 13,047 Union and 10,699 Confederate casualties. Among these was Confederate Army commander General Albert Sidney Johnston, who was killed on April 6, 1862. In all of American History, he is the highest-ranking American military officer ever to be killed in action.

The battle also changed the way that both armies conducted their maneuvers. Determining that no position was truly secure unless improved with picks and shovels, soldiers were required to dig deeper and more often as the war went on. (See Pick & Shovel Warfare in the Civil War)

Shiloh National Cemetery

In 1866, the War Department established a cemetery on the Shiloh Battlefield, in southwestern Tennessee. To bury the dead not only from the April 6-7, 1862, Battle of Shiloh but also from all the operations along the Tennessee River, workers began building the “Pittsburg Landing National Cemetery.” Changed to “Shiloh National Cemetery” in 1889, the cemetery holds 3,584 Civil War dead, 2,359 of whom remain unknown. In the fall of 1866, workers disinterred the dead from 156 locations on the battlefield and 565 different locations along the Tennessee River. Wooden headboards first marked each grave but were replaced in 1876 and 1877 by granite stones. Tall stones marked the known dead, and square, short stones denoted unknown soldiers.

Workers built a stone wall around the cemetery in 1867 and fashioned ornamental iron gates at the entrance in 1911. A superintendent cared for the cemetery until it was officially consolidated with Shiloh National Military Park in 1943. The results of so much labor produced what one observer called “the handsomest cemetery in the South.”

Although established as a Civil War burial ground, the Shiloh National Cemetery now holds deceased soldiers from later American wars. Many World War I and II, Korea, and Vietnam burials are in the newest section of the cemetery. There is also one Persian Gulf War memorial. Total interred in the cemetery now stands as 3,892. Although the cemetery was officially closed in 1984, it still averages two or three burials a year, mostly widows of soldiers already interred.

There is perhaps no more honorable title than that of “American soldier.” Inscribed on the Tomb of the Unknowns at Arlington National Cemetery are the words, “Here Rests in Honored Glory, An American Soldier, Known But to God.” Thousands of known and unknown American soldiers rest in national and private cemeteries worldwide, as they do in Shiloh National Cemetery. Near the riverbank lies six Wisconsin color-bearers, all killed in action as they carried their regimental standard into the heat of battle. Just to their west lies Captain Edward Saxe of the 16th Wisconsin, the first Federal officer killed in the battle. Near him lies the teenage drummer boy John D. Holmes of the 15th Iowa. Nearby, two Confederates lie amid so many Union soldiers, their pointed tombstones in stark contrast to the rounded stones of United States soldiers. Across the cemetery lies J.D. Putnam of the 14th Wisconsin, whose 1862 burial inscription on the foot of a tree, cut by his friends in the heat of battle, was still legible in 1901. Near him lies George Ross, a Revolutionary War soldier. In the newest sections of the cemetery, many more recent American soldiers lie in honored glory. One memorial honors a Persian Gulf veteran killed in service. Most sadly, interspersed between all these American soldiers are countless gravestones with only a number identifying them. They, too had lives, mothers, perhaps wives, sons, and daughters, fears, hopes, and dreams. All these soldiers, known and unknown, served their country and gave the ultimate sacrifice. They deserve the honor and tribute of Americans and the title “An American Soldier.”

A large Confederate monument commemorates the southern soldiers who fought and died at the Battle of Shiloh.

With the exception of the two Confederates, all those interred in the national cemetery are United States soldiers. There has been heated debate concerning why the Confederates are not buried in the cemetery. There are several reasons. Regulations require that only veterans of the United States military can be buried in national cemeteries. As Confederates were technically not United States personnel, they have traditionally been buried elsewhere. Although Congress stipulated in 1956 that Confederate soldiers should be treated the same as United States soldiers, the practice of burying Confederate remains in places other than national cemeteries still exists. Similarly, when taken in the context of Civil War-era events, the practice of burying Confederates in national cemeteries was almost nonexistent. The Federal government’s view of former Confederates in 1866, when the cemetery was established, was that of traitors, revolutionaries, the enemy. Burying Confederates in national cemeteries in 1866 would be synonymous with burying American Revolutionary War soldiers in British military cemeteries.

As a result, the Confederates who died at Shiloh were not disinterred from their battlefield graves. They remain on the field in several large mass graves and many smaller individual plots. As many as eleven or twelve mass graves exist, but the park commission that created the battlefield could only locate five. Those five are now marked, the largest of these being the mass grave at Tour Stop # 5.

National cemeteries and soldier plots are special places, and Shiloh is no different. Buried with these American soldiers is the honor, courage, and sacrifice of an entire American generation. Indeed, these soldiers gave the ultimate sacrifice for what they believed in. Can we of today’s generation learn from these soldiers and meet our own challenges and problems with the same dedication they possessed? Despite different means to wage war, different enemies to face, and different objectives to win, we are still fighting for the same causes they were: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Perhaps President Abraham Lincoln said it best when he declared “that these dead shall not have died in vain,” but that this nation “shall not perish from the earth.” It is our duty to take the standard and make sure Lincoln’s vision is never lost.

Shiloh Indian Mounds

About 800 years ago, a town occupied the high Tennessee River bluff at the Shiloh plateau’s eastern edge. Between two steep ravines, a wooden palisade enclosed seven earthen mounds and dozens of houses. Six mounds, rectangular in shape with flat tops, probably served as platforms for the town’s important buildings. These structures may have included a council house, religious buildings, and the town’s leaders’ residences. The southernmost mound is an oval, round-topped mound in which the town’s leaders or other important people were buried.

This town was the center of a society that occupied a twenty-mile-long stretch of the Tennessee River Valley. Around 1200 or 1300 A.D., inhabitants moved out of this part of the Tennessee Valley, perhaps to upriver locations now submerged under Pickwick Lake.

Since the Shiloh society disintegrated several hundred years before there were written records to tell us who they were, it is not clear whether or how the Shiloh residents were related to later societies like the Choctaw, Chickasaw, or Creek Indian tribes.

Archaeologists refer to the society centered at Shiloh as a “chiefdom.” The chief would have been the most important political leader as well as a religious figure. Probably a council, composed of elders and respected members of the community, shared power with the chief. Close relatives of the chief would have been treated like nobility; some were probably buried in “Mound C.”

The Residents of the Shiloh site were farmers. Corn was their most important food. They also grew squash and sunflowers, as well as less familiar crops such as goosefoot, marsh elder, and may grass. In addition to their cultivated crops, they also ate a wide variety of wild plants and animals. The most important wild plant foods were hickory nuts and acorns. Most of their meat came from deer, fish, turkey, and small animals such as raccoon, rabbit, and squirrel.

In addition to the Shiloh site, the chiefdom included six smaller towns, each with one or two mounds, and isolated farmsteads scattered on higher ground in the river valley. Downstream on the river’s eastern bank, in Savannah, Tennessee, once stood another palisaded settlement with multiple mounds. Many of the Savannah mounds were actually built much earlier, about 2,000 years ago, but the site was reoccupied at roughly the same time as the Shiloh site. We don’t know whether these two towns were occupied at exactly the same time. Modern buildings in Savannah have obliterated most of the prehistoric sites.

The Shiloh chiefdom had as neighbors other chiefdoms in what is now Alabama, Mississippi, and western Tennessee. Most of the chiefdoms occupied portions of the major river valleys, like the Tennessee and Tombigbee Rivers. Some of the neighboring chiefdoms would have been hostile to the Shiloh chiefdom, while others were linked to Shiloh by political alliances. Archaeological evidence of these alliances survives in the form of “prestige goods” that chiefs exchanged as tokens of their friendship. It can often be determined where specific prestige goods were made, which reveals who these indigenous people were trading with. In Shiloh’s case, it is known that political ties existed with the powerful chiefdom at Cahokia, near St. Louis. In contrast, there is no evidence of political ties to chiefdoms in central Tennessee.

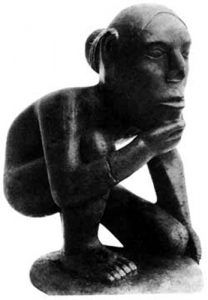

The First Archaeological excavation at Shiloh took place in 1899 when Cornelius Cadle, chairman of the Shiloh Park Commission, dug a trench into “Mound C.” There, he found the site’s most famous artifact, a large stone pipe carved in the shape of a kneeling man. Now on display in the Tennessee River Museum in Savannah, Tennessee, this effigy pipe is made of the same distinctive red stone and is carved in the same style as a number of human statuettes from the Cahokia chiefdom, located in Illinois near St. Louis.

Survey work in the winter of 1933-34 revealed numerous small, round mounds at the Shiloh site, each about one foot high and ten to twenty feet in diameter. Here were found the remains of wattle-and-daub houses. These structures had walls of vertical posts interlaced with branches (wattle), coated with a thick layer of clay (daub). Each house had a fireplace in the center of the floor. A palisade wall, also made of wattle and daub, protected the site.

The early inclusion of the mounds area within the Shiloh National Military Park boundary has protected the site from any modern use. Because the Shiloh site has never been disturbed by the plow, the daub of collapsed walls still stands as low rings or mounds. Shiloh is one of the very few places in the eastern United States where remains of prehistoric houses are still visible on the ground’s surface.

Shiloh National Military Park

Congress established Shiloh National Military Park on December 27, 1894, to commemorate the April 6-7, 1862 battle that raged around Shiloh Church and Pittsburg Landing. The Secretary of War appointed a commission to oversee its building and development, which was made up of veterans, who relied heavily on its appointed historian, David W. Reed, a member of the 12th Iowa, which had fought squarely in the Hornets’ Nest. Reed wielded much power in locating troop positions, making sense of the confusing reports, and interpreting the battle to the public. With images of battle in his mind and a growing consensus that the Hornets’ Nest was the central event of Shiloh, Reed developed the Hornet’s Nest interpretation of the battle, which still dominates Shiloh historiography today.

Producing more than 23,000 casualties, the battle was the largest engagement in the Mississippi Valley campaign during the Civil War. Originally under the War Department, Shiloh National Military Park was transferred to the National Park Service in the Department of the Interior in 1933. Currently, the park has over 4,200 acres. The Corinth Battlefield Unit encompasses roughly 240 acres with the potential for a total of 800 acres.

Besides preserving the site of the bloody April 1862, battle in Tennessee, the park commemorates the subsequent siege, battle, and occupation of the key railroad junction at nearby Corinth, Mississippi. It also protects and preserves the Shiloh National Cemetery and the Shiloh Indian Mounds. Both Shiloh and Corinth feature visitor centers. A 12.7-mile auto tour route, with 20 stops, takes you through the Shiloh Battlefield. The park will provide you with a map of the battlefield and brief commentary for each stop. The entire route is accessible to school buses.

Both Shiloh and Corinth host several living history events throughout the year, mostly from April to October. The major event each year is the Battle of Shiloh anniversary living history demonstration. The park is open all year, with the exception of Christmas Day.

More Information:

Shiloh National Military Park

1055 Pittsburg Landing Road

Shiloh, Tennessee 38376

Shiloh Battlefield Visitor Center – (731) 689-5696

Corinth Civil War Interpretive Center – (662) 287-9273

Compiled by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated January 2021.

Also See:

Tennessee – The Volunteer State

Source: National Park Service