~~

Not long after adventurers began to explore the American West, the inevitable saloons began to pop up. The first saloon was allegedly established at Brown’s Hole, Wyoming, in 1822 to serve fur trappers. In the years after, hundreds and thousands of saloons would follow, serving cowboys, soldiers, lumberjacks, businessmen, lawmen, outlaws, miners, and gamblers. Known by other names such as cantina, grogshop, gin mill, watering trough, and many others. By the late 1850s, the term saloon had begun to appear in directories and common usage as a term for an establishment specializing in beer and liquor sales by the drink, with food, lodging, gambling, dancing, and brothels serving as secondary businesses. By 1880, the growth of saloons was in full swing.

“If I had to live my life over, I’d live over a saloon.”

— W. C. Fields

Commercial Hotel Saloon, Anaheim, California, 1910

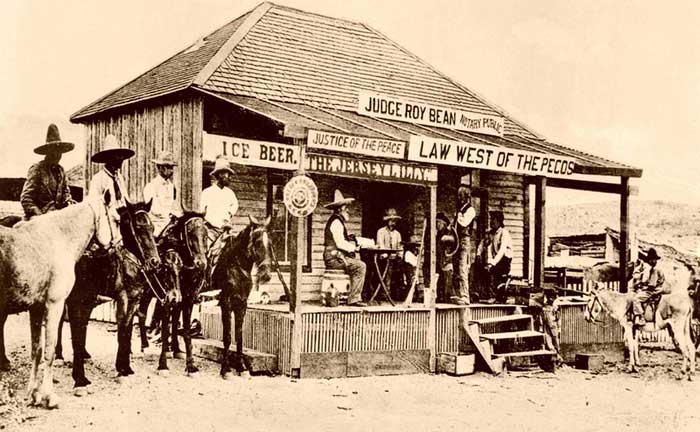

Judge Roy Bean’s Saloon in Langtry, Texas

Pappe’s Saloon in Kingfisher, Oklahoma, 1901

Thornton-Curry Saloon, Lincoln, New Mexico, 1890s

Bird Cage Theatre, Tombstone, Arizona

Carissa Saloon, South Pass City, Wyoming

Commercial Hotel Saloon, 1910, Anaheim, California

The saloon inside the Commercial Hotel in Anaheim, California, in 1910. It was located at 182 West Center Street (now Lincoln Avenue) at the corner of Lemon Street. Built by Anaheim’s second mayor, Henry Kroeger, in 1872, it was first known as the Anaheim Hotel. It was later sold to the hotel’s manager, Max Nebelung, and by 1890, the hotel’s name was changed to the Commercial Hotel.

This Vintage photograph shows two men standing behind the bar and several customers standing or seated throughout the room. Visible is the cash register, liquor bottles, and glassware in cabinets behind the bar; three spittoons along the foot-rail in front of the bar; wall clock and various pictures hanging on wall-papered walls; with lighting provided by four bare electric light bulbs and two kerosene lamps.

In 1905, the Commercial Hotel was sold to John Ziegler, who, in 1916, replaced the old hotel with a new $40,000 four-story brick building at the same location. Called the Hotel Valencia, it stood until May 1977, when it burned down.

John Ziegler appears to have kept the same long bar in the original Commercial Hotel when he built the new Hotel Valencia. However, behind the bar is now a large mirror framed by ornate woodwork. In this image, a bartender and owner, John Ziegler, are behind the bar, with a customer standing at the bar rail. The cash register, liquor bottles, and glassware are visible behind the bar; two spittoons along foot-rail in front of the bar; a wooden barrel and double wooden doors leading to the dining room are at far right; a wall clock and various posters hang on wall-papered walls, and lighting is provided by four lamps hanging from the ceiling.

Judge Roy Bean’s Saloon in Langtry, Texas

Judge Roy Bean, operating out of Langtry, Texas, was the self-appointed justice of the peace, referring to himself as the “Only Law West of the Pecos.” Though his justice methods, carried out in this combination saloon/courtroom, were somewhat odd, they were always final. In addition to Bean’s colorful “justice” meted out in his saloon, patrons could also enjoy billiards and “opera house” productions. Both the village of Langtry and the original Jersey Lilly Saloon was supposedly named in tribute to the English actress Lillie Langtry, with whom the judge was infatuated. Though they never met, she did visit the saloon in 1904, shortly after the judge died at the age of 78 following a drinking spree.

Today, the Jersey Lilly Saloon and Courtroom adjoins a Visitor’s Center in Langtry, Texas, that interprets the highlights of Judge Roy Bean’s career and provides travel information for the Lone Star State. Langtry is all but a ghost town today.

Meeker, Colorado Saloon, 1899

An interior view of a saloon in Meeker, Colorado, shows two men posing behind the long wooden bar, from which towels for the customers hang, a foot rail sits below, and a large spittoon is on the floor in the middle. Behind the bar is a large wooden fixture that features one rectangular and two oval inset mirrors. Reflected in the mirror are what appears to be a stuffed deer and bighorn sheep head. Bartop displays a cash register, bottles, and glassware. From the back fixture, hangs patriotic bunting and two small American flags. The walls are decorated with advertising posters and a calendar. The saloon is lit by a kerosene lamp hanging from the ceiling, and a spittoon is sitting on the floor. Note the dog on the floor left of the bar.

Meeker, Colorado, situated in the wide fertile valley of the White River in northwestern Colorado, is, and always has been, relatively isolated. This was not one of the many mining towns for which Colorado is well known but, rather, a farming community. The town was named for Nathan Meeker, the United States Indian Agent who was killed, along with 11 other people, by White River Ute Indians in the 1879 Meeker Massacre. Today, Meeker is called home to about 2,500 people.

When Meeker was first established, it was known for its hunting, drawing visitors in from all over the nation, including Theodore Roosevelt. This image of a Meeker Saloon was taken during that time.

Pappe’s Saloon in Kingfisher, Oklahoma, 1901

Richard Pappe, Sr. owned a saloon in the 300 block of North Main Street in Kingfisher, Oklahoma, just south of where the Kingfisher Times is situated today. An immigrant from Germany, he and his wife and their 10-month-old son came to the United States in 1882. They made their way to Newton, Kansas, where the couple established a bakery. However, when the Oklahoma Land Rush began in 1889, they, along with hundreds of others, staked their claim to a homestead in Kingfisher, Oklahoma. One of the founders of the city, he and his family and descendants, would achieve the American dream by establishing saloons and several other businesses in the area.

Pappe’s Saloon was established in 1889 in an existing building that had formerly been in an ice cream parlor. At that time, it was just a single-story building. When Oklahoma became a state in 1907, Prohibition was declared, and the business became a cafe. Over the years, a second story was added, and the building has served numerous purposes.

The photos display a long, ornate wooden bar, backed by a large mirror and liquor bottles. Spittoons and a foot rail can be seen at the front bottom of the bar. A large cigar case sat to the right of the long bar. Both ceilings and walls were wallpapered, and posters, paintings, and a calendar adorn the walls. Lighting is provided by lamps hanging from the ceiling. Note on the top photo, towels hanging from the bar. In the “old days,” bars didn’t provide napkins. Customers used the towels to remove the beer foam from their mustaches.

The photos display a long, ornate wooden bar, backed by a large mirror and liquor bottles. Spittoons and a foot rail can be seen at the front bottom of the bar. A large cigar case sat to the right of the long bar. Both ceilings and walls were wallpapered, and posters, paintings, and a calendar adorn the walls. Lighting is provided by lamps hanging from the ceiling. Note on the top photo, towels hanging from the bar. In the “old days,” bars didn’t provide napkins. Customers used the towels to remove the beer foam from their mustaches.

Photos and information, courtesy Pappe Family Website

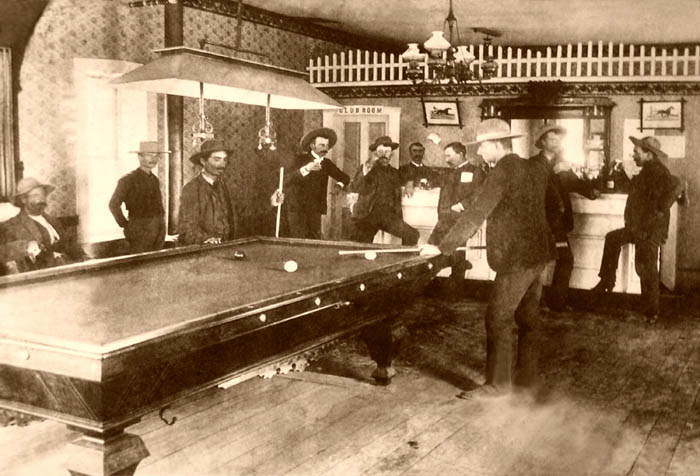

Thornton-Curry Saloon, Lincoln, New Mexico, 1890s

Also called the Bank Exchange Saloon, J. Y. Thornton and George Curry owned this place. The saloon featured a billiard’s table with the bar at the back of the room. Behind the bar is a mirror and shelves, and it appears the bar had the typical foot rail, on which a cowboy is resting his foot. Walls are adorned with patterned wallpaper and a few prints. Lighting provided by lamps hanging from the ceiling and the floor is made of plank boards.

A native of Pennsylvania, J. Y. Thornton came to New Mexico as a soldier in the United States Army in 1870. After serving for five years with the Fifteenth Infantry stationed at Fort Stanton, he was discharged in 1875. Afterward, he engaged in the cattle business at Fort Stanton with George Curry for five years, and the two opened the saloon and hotel in Lincoln, New Mexico, in about 1880. Thornton also owned the Pioneer livery stable in Lincoln. The very next year, a bit of excitement took place right across the street from the saloon when Billy the Kid, who was housed in the jail, awaiting execution, killed his guards and escaped on April 28, 1881. Thornton moved from Lincoln to Roswell, New Mexico, in 1895.

Thornton’s partner in the saloon and hotel was George Curry, a Louisiana native working as the post trader at Fort Stanton, where the two met. Finding he had an interest in politics, Curry served as the deputy treasurer, county clerk, county assessor, and sheriff of Lincoln County. He would later enlist in Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders and serve as a member of the New Mexico Territorial Senate and Territorial Governor.

The old Thornton & Curry Saloon still stands in Lincoln, New Mexico, housing a restaurant today.

Bird Cage Theatre, Tombstone, Arizona

The bar at the Bird Cage Theatre in Tombstone, Arizona by Kathy Alexander.

The famous Bird Cage Theatre in Tombstone, Arizona, opened its doors on December 25, 1881, and for the next eight years would never close, operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. Also called the Birdcage Opera House Saloon, the establishment featured a saloon, gambling parlor, theatre, and a brothel. In no time, the “theatre” gained a reputation as one of the wildest places in Tombstone, Arizona, so bad that the few self-respecting women in town refused to even walk near the place. The New York Times reported in 1882 that “the Bird Cage Theatre is the wildest, wickedest night spot between Basin Street and the Barbary Coast.”

During the years that the theatre was open, the wicked little place witnessed several gun and knife fights that took some 26 lives and left 140 bullet holes in the ceilings, walls, and floors, many of which can still be seen today.

The theatre was called the “Bird Cage” because of its 14 crib-style compartments suspended from the ceiling. Here, the painted ladies would pull the drapes and “entertain” their customers at some of the most exorbitant prices ever heard of in the Old West.

In 1889, the Bird Cage closed its doors as a brothel and a saloon forever, left with all of its original contents. For the next three decades, it would sit languishing in the desert sun. Amazingly, during this time, its bar, furnishings, fixtures, and drapes were not sold. In 1934, the Hunley family reopened the Bird Cage Theatre as a tourist attraction, keeping all the original fixtures and furnishings in place. Today, the Bird Cage Theatre stands as a museum, still run by the Hunley family, providing a dusty and accurate picture of the 19th century.

The hand-painted stage, which once featured the likes of Eddy Foy, Lotta Crabtree, Lillie Langtry, Lola Montez, and Lillian Russell, still stands, along with the orchestra pit and its massive Grand Piano. The gambling parlor continues to feature the actual table where Doc Holliday once dealt faro, and lining the walls are photographs of the many who passed through its doors, as well as original paintings that hung in the establishment. The original bar still stands and on display is Tombstone’s famous horse-drawn hearse called the Black Moriah. The first “vehicle” to ever have curved glass, it is trimmed out with gold and reportedly worth nearly two million dollars. Ruffled-up beds and scattered clothes are authentic, as well as the original faded carpets, drapes, and furniture.

The front room in the famous Bird Cage Theatre, which now serves as a museum, continues to feature its original wooden bar, paintings, and many of its fixtures. The bar is backed by the typical long mirror, along with shelves for bottles and glassware. The cash register also sits here. Original paintings, prints, and posters can be seen in the mirror’s reflection. Lighting is provided by fixtures hanging from the ceiling.

The Bird Cage Theatre is Tombstone’s most authentic attraction, one of the Old West’s most famous landmarks, and a definite “must stop” while in Tombstone. It is also allegedly one of the most haunted places in Tombstone. But that’s another story. See it HERE!

Also See:

Tombstone Historic Buildings – Gallery & Descriptions

Tombstone – The Town Too Tough To Die

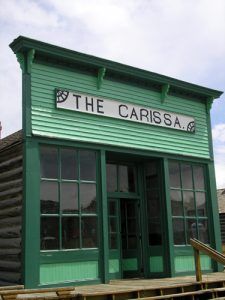

Carissa Saloon, South Pass City, Wyoming

The Carissa Saloon in South Pass City, Wyoming, has been fully restored with period furnishings and artifacts from the area that would have been typical for a simple saloon like the Carissa. Wood burning stoves were often found in saloons, and the interior displays the expected long wooden bar, simple furnishings, and a treat for the customers – a piano. The walls are decorated with antlers, a deer head, and posters.

One of the longest-running saloons in South Pass City, the Carissa Saloon was built by James Smith in about 1890. It takes its name from the area’s richest gold mine located on the hill above the town. The saloon was a simple affair, offering basic furnishings and refreshments to its customer. The simple rectangular building with a typical false front is approximately 21′ x 31′ with a storage room constructed into the hill behind it. The original flooring was 3 1/2″ tongue and groove flooring, the walls of the front room were painted gypsum board, and the rear room was built of logs. The ceiling in the main room was a painted board ceiling, and in the rear room, logs were exposed.

The saloon passed through several hands during its early years, and by the 1940s, it was run by John “Shorty” Nichols, who was known by the locals as a storyteller. It was later abandoned and began to deteriorate. Further damage occurred in 1960 when a road grader went out of control and struck the front of the building. In 1977 the building was restored and opened to the public as part of the South Pass Historic Site.

Also See:

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West

South Pass City – An Authentic Ghost Town

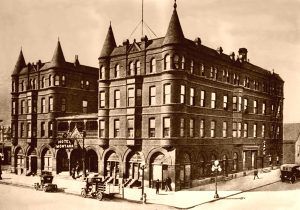

Montana Hotel Saloon, Anaconda, Montana

The saloon inside the popular Montana Hotel in Anaconda, Montana, was elegantly adorned. Like other saloons of the period, it featured a long wooden bar with a foot rail, but, unlike many others of the time, this one included bar stools, and no spittoons can be seen on the floor. Behind the bar, three arched mirrors are framed by ornate pedestals and carvings, and space is filled with bottles, glassware, and a cash register. Glass sconces provide lighting. A large wallpaper pattern can be seen in the mirror’s reflection, along with a painting.

Backed by the powerful San Francisco, California syndicate of Hearst, Haggin, and Tevis, Marcus Daly built the world’s largest smelter on Warm Springs Creek between 1883 and 1889. Along with the smelters, Daly envisioned a substantial city and filed the original townsite plat on June 25, 1883. By the fall of 1884, Anaconda’s 80 buildings included seven hotels and boarding houses, and twelve saloons. In 1888, Marcus Daly and his associates established the Montana Hotel Association and began construction on the new hotel, which was completed in the spring of 1889 at an estimated cost of $125,000. Modeled after New York City’s Hoffman House, the hotel was designed by Chicago Architect W.W. Boyington, using a composite style of French Renaissance and Romanesque architecture.

The four-story structure was built of local red brick with terra cotta ornamentation and a 34 foot wide central arched entrance. The hotel interior included 185 rooms with modern amenities, like telephones, steam heat, and an electric elevator. Many rooms had canopied beds, a marble fireplace, and Persian rugs. The full basement was equipped with a servant’s dining room, a laundry, boilers, and a dynamo for electric light generation. The first and second floors finished in red oak and eastern pine, contained the main dining room, a ladies’ ordinary, a saloon, chandeliered ballroom, drug store, and barbershop. After Marcus Daly died in 1900, the Montana Hotel underwent extensive remodeling, costing $96,000 under the ownership of the Anaconda Company.

In 1954, the building was purchased by Edison and Bell, Inc. of Kalispell, Montana. The firm operated the hotel until 1959, at which time plans for demolition were considered. To combat this action, citizens of Anaconda formed the Montana Hotel Corporation and purchased the structure, renaming it the Marcus Daly Hotel. A restoration project was undertaken in 1964, and a modern motel unit was built to the rear of the original structure. In 1975, heavy financial burdens and potential bankruptcy faced the Montana Hotel Corporation. The following year, the building was sold to a local developer, and more than 2,000 hotel items were sold at auction. A year later, it stood abandoned.

Then, an aggressive program of structural renovation was begun, including the removal of the hotel’s two upper stories. The remaining space was then used for retail and office space.

Located at the corner of Park and Main Streets, there is currently a group in Anaconda that is exploring the possibility of returning the historic hotel to its former glory.

Hotel Montana building in Anaconda, courtesy Billings Gazette.

Also See:

Alamo Saloon, Abilene, Kansas

The Alamo Saloon in Abilene, Kansas was the most elaborate of the saloons in the many Kansas Cowtowns.

Vintage Abilene, Kansas

In 1867, when the Kansas Pacific Railway pushed westward through Abilene, it soon became the first “cow town” of the west when Joseph G. McCoy purchased 250 acres of land, built a hotel called the Drover’s Cottage, and established stockyards equipped for 2,000 heads of cattle, and a stable for their horses. Though the new shipping point stimulated the growth of the town, it also brought in many undesirable characters, including gamblers, confidence men, cowboys, soiled doves, and more. Desperately seeking a lawman, the City of Abilene hired Thomas J. “Bear River” Smith, an extremely competent officer from Colorado. When an outlaw killed Smith, his successor was none other than the famous Wild Bill Hickok, already well-known for deadly marksmanship and gunfighting skills. During these rowdy days of Abilene, it sported many saloons, including the Alamo, which Hickok was known to spend much time in and was apparently made his unofficial “headquarters.”

The original saloon was housed in a long room with a 40-foot frontage with an entrance at either end. At the west entrance were three double glass doors. Inside and along the front of the south side was the bar with its array of carefully polished brass fixtures and rails. From the back, bar arose a large mirror, which reflected the brightly sealed bottles of liquor. On the walls were huge paintings in cheaply done imitations of the nude masterpieces, gaming tables filled the floor, and the saloon even boasted an orchestra. In the height of the season, the saloon was the scene of constant activity, with much noise emanating such as badly rendered popular music, coarse voices, ribald laughter, and Texan “whoops,” punctuated at times by gunshots.

On the street near the Alamo, a famous Abilene gunfight took place between City Marshal Hickok and Phil Coe. On the night of October 5, 1871, a number of Texas cowboys were celebrating by drinking and stopping in Abilene’s saloons.

The Junction City Union newspaper published this account of the incident on October 7th and references the Alamo Saloon in the story:

“Two men were shot at Abilene, Thursday evening… Early in the evening, a party of men began a spree, going from one bar to another, forcing their acquaintances to treat, and making things howl generally. About 8 o’clock, shots were heard in the Alamo, a gambling hall; whereupon the City Marshal, Hickok, better known as ‘Wild Bill’, made his appearance. It is said that the leader of the party had threatened to kill Bill ‘before frost.’ As a reply to the Marshal’s demand that order should be preserved, some of the party fired upon him when, drawing his pistols ‘he fired with marvelous rapidity and characteristic accuracy,’ as our informant expressed it, shooting a Texan, named Coe, the keeper of the saloon, we believe, through the abdomen, and grazing one or two more. In the midst of the firing, a policeman rushed in to assist Bill but unfortunately got in the line of his fire. It being dark, Bill did not recognize him and supposed him to be one of the party. He was instantly killed. Bill greatly regrets the shooting of his friend. Coe will die. The verdict of the citizens seemed to be unanimously in support of the Marshal, who bravely did his duty.”

Hickok then arrested Coe for discharging a gun within the city limits. Coe died several days later.

Alamo Saloon Interior, Abilene, Kansas by Kathy Alexander.

Sometime after Abilene’s illustrious cowtown days ended, the old Alamo Saloon burned down. However, years later, a 3/4 scale replica of the saloon was built in Abilene’s Old Town, which can be visited today.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2021.

Also See:

Abilene – Queen of the Kansas Cowtowns