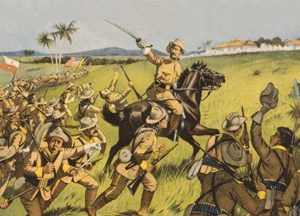

Theodore Roosevelt and the Roughriders by Kurz & Allison

Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th President of the United States, was also a military officer, author, naturalist, cowboy, and conservationist. He served as president from 1901 to 1909.

Theodore, often called “Teddy,” was born in New York City, New York, on October 27, 1858, to businessman and philanthropist Theodore Roosevelt Sr. and socialite Martha Stewart “Mittie” Bulloch. He was descended from an old Dutch family that came from Holland in 1644 and settled in New Amsterdam, which New York City was then called. His father, Theodore Roosevelt, was a glass merchant, a figure in city affairs, and a philanthropist widely respected and beloved; his mother, Martha Bulloch, was a woman of unusual beauty and charm, of cool good sense and passionate devotions. Theodore was, from his birth, a frail boy who had asthma and other ailments. For weeks, he was forced to keep to his bed, and the rough-and-tumble of boyhood was withheld from him during his early years. He learned to read while still in skirts, and before he was out of the nursery age, books had become companions to him and comforters in pain. His sisters, brother, and friends were his devoted followers, who found the stories he told them, hour after hour, altogether thrilling.

Theodore Roosevelt at age 11.

He went to school briefly at Professor McMullen’s Academy near Madison Square. Still, his health permitted him no regular schooling, and tutors and governesses gave him an uneven elementary education, which he extended and deepened by wide reading of heroic tales, natural history, science, and biography. When he was nine, he was taken through Europe, but, to judge from the journal he kept, he gained nothing from it except a small boy’s spread-eagle homesickness for his own land. Another trip to Europe four years later opened his eyes. He had, by that time, become an ardent naturalist, and Egypt and the Continent were interesting for their birds, if not for their monuments. He spent a winter in a German family in Dresden and returned to America with an understanding of foreign lands, giving him a genuine appreciation of his own. Still handicapped by his physical frailness, he prepared himself for college.

Meanwhile, he had acquired certain ideals of life and conduct which deeply influenced his character. He was a notable hero-worshipper, with his father as his greatest hero, and behind him, and heroes he found in books. He measured himself by them, found himself wanting both in courage and physical strength, and doggedly set to work to repair the defects. He took boxing lessons and exercised with a persistence that did not decrease in the gymnasium his father installed for him. The world of the outdoors was a source of delight and adventure. His boy’s love for birds and insects developed into the scientist’s ardor for solid knowledge. When he went to college in the autumn of 1876, it was with the determination to become an animal naturalist.

His years at Harvard were years of growth and joyous companionship. He studied hard, read widely and deeply, and plunged into a dozen different undergraduate activities, from boxing and fencing and football to acting and writing, Sunday school teaching, and discussion of art. He romped one day, wrote history the next, made many friends, gained a few devoted followers who prophesied great things for him and grew in body and mind.

He graduated in June 1880. Shortly afterward, he married Alice Lee of Chestnut Hill, the radiant center of the group of boys and girls with whom he had “run” during his Harvard years. They went to Europe, where Theodore climbed the Matterhorn for no particular reason except that a pair of Englishmen with whom he had talked seemed to think that they were the only ones who had ever climbed it or ever would, and returned to America, more ardently American than ever, and settled in New York.

He then gave up his intention of becoming a naturalist without, however, being able to decide what he would become. With no great enthusiasm for the law, he entered the Columbia Law School at the same time, the law office of his uncle, Robert Roosevelt. In the meantime, he completed a book entitled The Naval War of 1812, which he had begun in college, looked at the political world of his native city, and joined the Republican Club of the Twenty-first Assembly District.

He became a factor, if not power, there at once. On the initiative of an intelligent, keen-witted Irishman named “Joe” Murray, a local “boss,” was nominated for the Assembly within a year and elected. In Albany, he sprang almost at once into leadership. Before his first term was over, he was a national figure; at the end of his third, he was a force to be reckoned with in the Republican Party, head of his State delegation to the National Convention, the hero of young men, the hope of all who were working for the triumph of the better elements in American politics.

He gained his first fame through a fearless attack on a corrupt judge whom his party’s leaders were seeking shelter, but, with the real confidence of the public, he won through solid and persistent work against the odds for honest government and progressive legislation.

A personal catastrophe cut off entirely and, it seemed, forever, his political career. In February 1884, his mother died suddenly. The same night, his daughter was born, and 12 hours later, his wife died. He finished his term in the Assembly, did what he could to nominate the man of his choice at the Republican Convention in Chicago, failed, and hid, disheartened, on a ranch he had purchased the preceding autumn on the banks of the Little Missouri River in North Dakota.

In the two years or more that followed, the gay world of New York City and that other complex and tumultuous world of politics through which he had passed like a cyclone saw Theodore Roosevelt only for hurried glimpses, if at all. He had altogether resigned whatever political ambitions he might have had. He wanted to write, and he did write an entertaining book of hunter’s tales, a fresh and authoritative biography of Thomas H. Benton, another of Gouverneur Morris, and a volume concerning ranch life, but these were incidental. He had bought a great herd of cattle; he had called to his side from Maine a pair of old friends and stalwart backwoodsmen named Bill Sewall and Wilmot Dow; with them, he had built a house which he called Elkhorn, and he was now a ranchman whose life was bounded by the circle of cares and wholesome hardships and pleasures and perils that make up a ranchman’s days.

The bleak and savage country and the primitive conditions of life fascinated his imagination; the hardy men who were his companions gripped his affections and held them. The “women-folk” in Maine joined their husbands and took charge of Elkhorn and, for two years, made a home where the days passed in a round of manly endeavor and simple-hearted fellowship that in the memory of all who were a part of it lingered as a kind of pastoral idyll.

Working on the round-up, riding for days on end after stray cattle, hunting over the bare prairies and up the rugged peaks, Theodore Roosevelt won, at last, the strength of body he had set out to gain 15 years before. He won much else as well — an understanding of the common man and the West, a deeper appreciation of the meaning of democracy, a revived interest in life. His career as a ranchman ended in the autumn of 1886 when he went East to accept the Republican nomination for Mayor of New York City. In the mayoral contest, he was defeated by Abram S. Hewitt, the Democratic candidate. That same year, he married Edith Kermit Carow, and the couple would have five children, in addition to his daughter by his first wife.

In 1889, President Benjamin Harrison appointed him to the United States Civil Service Commission, and President Grover Cleveland retained him in that position. He resigned in 1895 to become president of the police board of New York City. By reorganizing the department in the interests of honesty and efficiency, he won national fame.

President William McKinley, in 1897, appointed him Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and he devoted his time to preparing for war with Spain, which he believed was inevitable. Roosevelt utilized the brief periods when he was Acting Secretary during His chief’s absence to carry forward the policy he deemed essential to national safety. It was by such almost surreptitious action that Dewey was provided with the coal and the ships, which ultimately enabled him to destroy the Spanish fleet at Manila.

When the war ended in April 1898, he immediately resigned and offered his services to the President to raise the cavalry regiments that Congress authorized. General Alger, Secretary of War, offered him the colonelcy of one of these regiments. He refused, asking that the regiment be given to his friend Leonard Wood, a veteran of the Indian wars, and at that time a surgeon in the army, with himself as lieutenant colonel. The offer was accepted. Early in May, the Rough Riders, as they were nicknamed, began to gather from all parts of the country in San Antonio, Texas. The training was brief but thorough. Six weeks after the regiment was organized, it stood trained and equipped on the firing line outside Santiago de Cuba.

The Rough Riders came under fire for the first time late in June at Las Guasimas, where Roosevelt commanded first the center and later the left wing. He revealed himself there like a brave soldier, an officer of calm judgment and leadership qualities altogether unusual.

The Battle of San Juan Hill was fought a week later. It was a small but, most bloody battle in which, owing to the inefficiency and blundering of the commanding general, the American casualties were altogether out of proportion to the numbers engaged. The day before the battle, Colonel Leonard Wood had been promoted to Brigadier General, and Roosevelt had been given command of the regiment.

All day, waiting for orders that did not come, he lay under the galling fire of Spanish guns with his men. One messenger after another, whom he sent for orders, was killed. At last, late in the afternoon, the command came to advance. He dashed forward, conspicuous on his white horse, plunged through the line of regulars obstructing his path, and led his men through the tall grass up the long hill. To the right and left of him, men fell, and the bullets sang with the sound of ripping silk past his ears. He remained untouched. At a barbed wire fence, he sprang off his horse and plunged on, his men close at his heels. He gained the first crest, pushing the Spaniards back; then another, and a third. Inspired by his cool courage, the American line advanced along the San Juan range. At dusk, the Spaniards were in full retreat from the city.

Roosevelt returned home a popular hero. The Republicans of New York State, facing defeat, recognized that in Roosevelt lay their only hope. He was nominated for Governor that autumn and elected after a hot and close campaign.

He immediately turned his attention to instituting reforms in the administration of the state business, especially in the management of canals, and he greatly extended the civil service examination system to state offices. By the close of his term, he had become the national leader of the progressive element of the Republican party. Despite his repeatedly expressed wishes, he was placed on the national Republican ticket as a candidate for vice president. At the death of President McKinley in September 1901, Theodore Roosevelt became president.

He retained President McKinley’s cabinet and continued many of his policies. He urged anti-trust legislation and the negotiation of reciprocity treaties. In his foreign policy, he took a firm stand in favor of maintaining American rights in questions over which other countries were disputing. His action in recognizing the newly-formed Republic of Panama after the rejection of the canal treaty by Columbia, his efforts to compel the South American republics to deal fairly with European governments, and his firm stand in favor of retaining the Philippines brought him much adverse criticism by the conservative elements in his party and the Democratic party. On the other hand, his aggressive domestic policy, honesty, sincerity, and executive ability won him a host of friends in both parties and among all classes.

Among the domestic events of his administration were the establishment of a permanent Census Bureau, the establishment of the Department of Commerce and Labor, a significant increase in the strength and efficiency of the navy, reorganization in the management of the army, and the settlement by Roosevelt in a personal capacity of the anthracite coal strike of 1902.

President Roosevelt was unanimously re-nominated by the Republican convention in 1904 and was opposed by Judge Alton B. Parker, the Democratic nominee, and by the candidates of several smaller parties. After a relatively quiet campaign, he was elected by the most significant plurality ever recorded for a presidential candidate and by a phenomenal majority in the electoral college. During his second administration, he continued his vigorous foreign policy and won a striking triumph in his successful efforts to terminate the Russo-Japanese War. Probably the most important event of the period, from a domestic standpoint, was the passage of a radical bill by the Interstate Commerce Commission for regulating railroad rates.

On March 4, 1909, Roosevelt retired from office after 20 years of executive work, during seven and one-half of which he had been President of the United States. He had planned an expedition to Africa to hunt and gather natural specimens for the Smithsonian Institution. On March 23, 1909, he, his son Kermit, and a party of naturalists sailed from New York. The trip to Africa lasted about a year, and on his way home, he made a tour of Europe.

In 1912 a new political party called the Progressive Party was organized and Roosevelt became its candidate for President. During the campaign, he toured the country making speeches, and on October 14, in Milwaukee, Minnesota, he was shot by a crazy man named John Schrank. Fortunately, the wound was not serious, and he resumed making speeches within a couple of weeks. In the November election, the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson, was successful, but Roosevelt received the next largest vote. Four years later, in 1916, he was again nominated by the Progressive Party but declined and recommended that this party unite with the Republican Party.

In 1913 and 1914, he visited South America and headed a scientific expedition into the unexplored regions of Brazil. The hardships he experienced in the jungles of South America caused a serious illness that left him very weak for a long time.

During World War I (1914-1918), Roosevelt was untiring in his advocacy of preparedness and Americanism. He severely criticized the administration for its policy of neutrality. After America entered the war, he proposed to raise a force of volunteers for service in France. His offer, however, was declined, and he devoted his time and energies to patriotic service at home.

Roosevelt died at his home at Sagamore Hill, Oyster Bay, Long Island, New York, on January 6, 1919. The Honorable Charles E. Hughes, in a memorial address before the Union League Club of New York, said of him:

“The career of Theodore Roosevelt has a lasting fascination for the young. There was nothing sordid or commonplace or unclean to mar it. His courage, steadfastness, faith, his deeds of daring, physical prowess, his resourcefulness, exploits as a hunter and explorer, intellectual keenness, his personal charm, and his dominating patriotic motive make their irresistible appeal, and in the shaping of the ideals of American youth for generations to come his most important service is yet to be rendered.”

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See:

Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota

Buffalo Hunting With Teddy Roosevelt

Presidents of the United States

Sources:

Hagedorn, Hermann; Theodore Roosevelt – A Biographical Sketch; Roosevelt Memorial Exhibition Committee, Columbia University, 1919.

Free Public Library of Jersey City; Theodore Roosevelt – A Brief Outline of His Life; 1920.