By Charles Carroll Goodwin in 1913

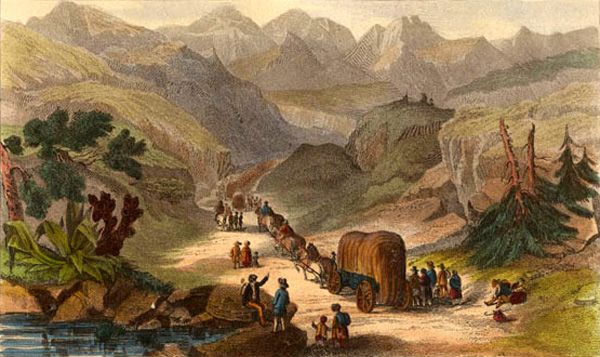

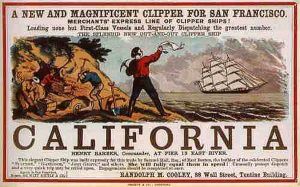

To California during the gold rush.

We all have, I hope, high and sincere reverence for the Pioneers; for those men and women who began their western march almost three hundred years ago; first in grotesque little ships across the Atlantic, and made their first stopping places on the eastern shore of the ocean; then a little later began to push their way into the wilderness and the Indians; as one generation sank into the earth another took up the slow march, pursuing its way until the deep woods gave place to smiling homes all the long way to and beyond the Mississippi.

Looking back, we remark a few of their achievements, the ongoing labor of their lives; the courage that bore them up; the poverty that bound them around in merciless coils; the self-sacrifices which they accepted as a matter of course; the tenacity with which they never failed to assert that their free citizenship should never be trenched upon; the carrying with them the little red schoolhouse; the high manhood, the divine womanhood which upheld them as they pushed their way.

All these and other characteristics shine out as we look back over the trails they blazed and mark the temples they up-reared, and to the eyes of the minds of all Americans, they make a picture of enchantment, not one tint of which fades as the years advance and recede.

But there came a time when the order of a hundred and fifty years was changed. Though for more than two hundred years the race had been toiling; though their heroic work had transformed a mighty section of the new world; though an empire of measureless natural wealth had been explored, the country was poor in that thing called money, the one thing that electrifies enterprise and provides a just reward for toil.

There came a whisper that on the other shore of the continent, gold had been discovered. This was swiftly confirmed by succeeding news, and then the exodus began.

Within a few months, there were tossed upon that western shore 250,000 men. They were nearly all young men, and every state of the then union was represented.

The journey had steadied and broadened them. Whether by the long trek across the continent, whether by lonely ships around Cape Horn or through the scramble and the rush by the pestilential Isthmus, they all had taken on new ideas by the experience they had been through.

As a rule, they were all more or less homeboys, and the best of them had a full quota of provincialism.

But this last melted away faster than it had ever before in any country.

The secret was that the mothers they kissed when they left home were American mothers. As the differences among American mothers are the differences in environment, it did not require long for their sons to recognize that fact.

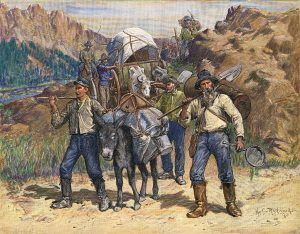

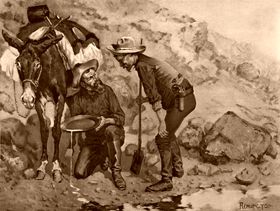

Many of the newcomers stopped on the seashore or in adjacent valleys, but I am not dealing with those today. The company never rested by the sea or in the peaceful valleys but hurried to the hills. For them, nothing would do but the native gold. The art of extracting it was simple and quickly learned. And when at night the clay’s proceeds were panned and cleaned and weighed, the miner held it before his eyes and invented the phrase: “That’s the stuff.”

And who were these miners? They were, as a rule, just American boys and young men. They had come from every field, from every school; they were, so to speak, the nation looked at through the big ends of the opera-glass.

All recognized that they were living in a land with no government, but they got together in the different camps and resolved that while there was no law, there should be order and that every man should be secure in what was rightly his.

Petty criminals fought shy of those camps. Sometimes there were disputes over business affairs. When they could not be settled privately, a court was quickly convened; a juror was never questioned about any bias or prejudice he thought he entertained or whether he had formed or expressed any opinion. He was simply asked if he could hear the case and decide according to the law and evidence. If he promised that, it was enough.

Some of those trials were most picturesque. Will Campbell was mining in a ravine a mile or two outside of Downieville [California]. One morning three or four miners came to him where he was at work, and one said: ”Mister, did you back in the states study law?’

Will replied that he did. Then it was explained to him that a big Pennsylvania Dutchman was trying to claim the ground that one of the boys owned, that a trial had been set for that afternoon, and they wanted Campbell to go to camp and try the case for them. Campbell replied, “All right, if one of you chaps will work my ground while I am gone, I will go.” This was agreed to, and Campbell went to the camp, tried, and won the case. He told me about it later, after he had become an eminent lawyer and judge.

He said: I was nineteen years old. I had just graduated; all the practice I had ever had any experience in was in the moot courts in the law school. I did not know a vast amount of law, but I had brought all my gall with me to California, and I suppose my argument that day was one calculated to scare away a mountain lion if he was an old and wary one and wished to avoid trouble.

‘I have never since experienced the self-satisfaction that was mine as I emerged from that room and walked out on the cleared space in front of the building. Many people congratulated me, and I swallowed it all as though it was my due. At last, the big Dutchman came along and said: ‘Mister Campbell, dot vas one great speech vot you made today.’ ‘Ah,’ I replied, ‘do you really think so, Uncle Billie ?’

‘Yaw, I tinks so.’ he said. ‘It just lacked but von ding to make it one very great speech.’

‘You really think so, Uncle Billie?’ I responded, ‘and pray what did it lack?’

‘It lacked sense’ was the curt answer. ‘The boys heard it, and it cost me all the dust I had mined for a week previous to get out of camp. I have heard of it from time to time ever since. But it did me lots of good. I have never since talked as learnedly as I did on that day. You see, the ordinary intellect can only stand about so much.”

Men who see no children for months have upon them a heart hunger which men in civilization can never comprehend.

And because of the absence of women and children, the wild beast in many a soul in the hills comes forth. There was no restraint upon them, and even a quartz mill runs away sometimes when the governor on the engine ceases to act.

Many drank, many gambled, many were killed in quarrels; many became boisterous and reckless, and lives were thrown away, which, under the restraint of good women’s eyes, might have made great names. It is said that the great Blucher of Prussia, riding over a dead-covered battlefield, said to an aide who was half overcome by the horror and pity of it: “Control yourself, General! When the winds and the deep-sea surges engage in battle, the shore next morning is piled deep with seaweed and other storm debris. It is nature’s way; these, too, are but debris cast up by the storm of yesterday.”

The graves on the tops and flanks of the Sierra are still the marks on the shore where that debris was thrown.

In another way, character was formed there. The resourcefulness which out of the rude surroundings developed into high manhood and superb citizenship; which with the means at hand accomplished mighty results; the resolution which hid suffering in men’s hearts; the transition which slowly strangled the brightest hopes ever nursed by mortals until they all went out; the self-sacrifices which were made, those making them wearing all the time the smile of contentment and peace, and giving up what was sweeter than life itself as the tired child drops its toys; acts of generosity and charity to make the angel of mercy weep for joy, these and kindred features made up the unseen tragedies that were enacted there, unseen but leaving their shadows on those heights.

What was visible was the joy and enthusiasm that reigned. What songs were sung, what stories were told, how vastly the vocabulary of the language was enlarged to produce words to fit all occasions, the echoes of the ghosts of them still roll like phantom drums through those hills.

Let no one think those camps were not schools of patriotism. All the papers from the lower cities were read and re-read; the magazines from the east were devoured, the new literature of California that rang out in the words of Bret Harte, of “Caxton of La Conte; of Barstow; of Bartlett; of Stout: of Coolbrith; of O’Connell; of Marshall, and the others, were household words in the camps. And the letters by the semi-monthly steamers, why talk about patriotism? When a letter comes to a young man from his mother or the daughter of some other young man’s mother five thousand miles away. He not only loves his country but loves the stokers that fed the coal to the furnaces in the ship that brought the letter.

And from among those men there grew up a race of scientists that had few instructors save as they set the hieroglyphics which nature had embossed upon the rocks and trees and hills, to words, and in their souls made histories of them, and through those histories caught the secret of the labors that had been going on there through the ages; the work of the earthquake, the glacier, the winds, the heat, the cold, the sunbeams — all the agents which the Infinite employs in rounding a world into form.

No other study is more impressive. With every leaf turned in that book of nature, the more accentuated comes the realization of the majesty, the mercy, and the power of the Infinite Architect which ages, before man had any existence save in the mind of God, caused the plans to be laid and approved through which, when man should materialize, a field would be ready for him where his mind and hands might find employment and where for earnest work a sure reward would be awaiting him; and where when he became great enough to understand how the work was framed and the reward provided, he would feel like “putting the shoes from off his feet.” because he was standing on holy ground.

And another character of men was developed there: strong men of affairs, captains of industry, who when they left the hills and entered into competition with ordinary men were found to be masters to take charge of any work that was presented, for to wrestle with the forces of nature and overcome the bastions and battlements which the mountains have up-reared in their own defense, make men stronger.

They were, even as was Jacob by his all-night wrestle with the Lord, strengthened by the labor, and because of it, like Jacob, they took on new titles among men.

If I have made the foregoing plain, it will be seen that while there were miners before those first California miners, and while there have been miners since in many ways their superiors as miners, there never was before, never has been since, just such a band as were they.

They had no homes with tender home influences to hold them in check; but they grew tenderer and more considerate of others because of the absence of those influences; they had no children of their own, but that made them fathers by the adoption of all the world’s children; many of them were wild and reckless, for there were at first no restraints upon them, no church spires to turn their gaze upward; they turned to trees which were higher than church spires, and to the sky under whose dim sheen they slept, and were perhaps nearer God because of their environments and the sentinel stars that kept solemn watch above them.

They worked out their lives; most of them, personally, are forgotten, but because they lived and toiled and kept watch, society should be kept secure against wrong, and the flag above them be kept stainless, the manhood of the whole coast was exalted. The influence they exerted has been an ennobling one to the whole coast ever since.

Charles Carroll Goodwin, 1913. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

About the Author: Charles Carroll Goodwin was a Nevada Judge, journalist, and newspaper editor who had an active interest in Nevada mining. During his lifetime, he authored numerous newspaper articles, short stories, poetry, and several books, including As I Remember Them, in 1913. The Old-Time Miners is a chapter of that publication.

Also See: