In 1854, the citizens of Tishomingo County invited two railroad companies, the Mobile & Ohio and the Memphis & Charleston, to build lines through the predominantly agricultural area. Within a year, the companies completed their surveys, and their two routes intersected in the north-central Tishomingo County. A small town grew up at the crossroads of the two new railroad lines, originally called Cross City. By 1855, the rapidly growing town changed its name to Corinth, after the crossroads city of ancient Greece. By 1860, Corinth was called home to about 1,500 people. When the Civil War began in 1861, Confederate and Union strategists recognized the importance of controlling Corinth due to its junction of two major rail lines. The town would become the site of two significant engagements: a siege of the town in the spring of 1862 and a bloody conflict in the fall of the same year.

The tracks still cross in the center of town, and trains still use them, but no one fights over them anymore. During the Civil War, as many as 300,000 soldiers moved through this tiny town in northeastern Mississippi, and the Union and the Confederacy fought to control the critical railroad crossroads. The evidence of their presence is everywhere.

A reconstructed earthen redoubt commemorates the men in gray who marched slowly and steadily against its walls and the men in blue who defended it in fierce hand-to-hand combat. And, if you look carefully, you can see miles and miles of earthen fortifications, some built to protect the crossover and some to help seize it. These trenches testify to a new kind of warfare tested here and would become common before the war ended in 1865.

In the years since the Civil War, Corinth has grown into a small city of about 14,000 people, but the general landscape has changed little.

The Siege of Corinth

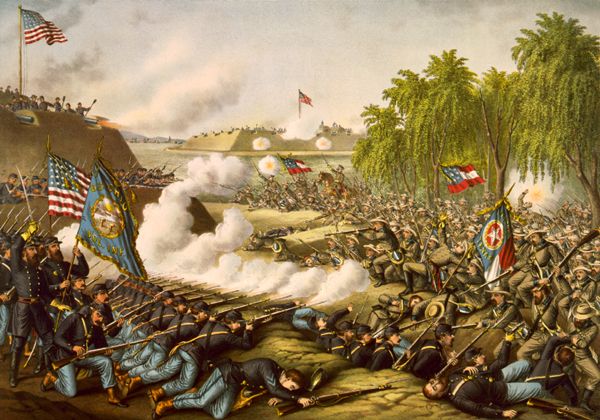

At the end of April 1862, Union Major General Henry W. Halleck’s powerful Army group of almost 125,000 men set out from Pittsburg and Hamburg landings in Tennessee towards Corinth, Mississippi. A Confederate force of about half that size, under the command of General P.G.T. Beauregard, waited for them behind five miles of newly constructed earthworks. Both commanders knew the importance of the coming battle. Halleck claimed that the railroad centers in Richmond, Virginia, and Corinth were “the greatest strategic points of the war, and our success at these points should be insured at all hazards.” Beauregard told his superiors: “If defeated here, we will lose the Mississippi Valley and probably our cause… and our independence.”

It took Halleck a month to travel the 22 miles to Corinth. The route crossed a series of low ridges covered with dense forests and cut by stream valleys and ravines. Moving his army through the rugged country while aligning it along a 10-mile front was slow and difficult. The weather was bad, and there was little good water. Dysentery and typhoid were common.

Ruse of the Whistles at Corinth, Mississippi

By May 2, the Union troops had closed within 12 miles of Corinth and felt their way forward from one line of entrenchments to another. The Confederates had constructed a defensive line of earthworks anchored on the Memphis and Charleston Railroad to the west, continuing around to the North of Corinth, crossing the Mobile and Ohio Railroad and Purdy Road, then turning south following the high ground commanding Bridge Creek and crossing the Memphis and Charleston Railroad well east of the crossover, and anchoring on the Danville Road, one-half mile east of the Mobile and Ohio. These earthworks guarded the eastern and northern approaches to Corinth.

By May 4, the Union army was within ten miles of Corinth and the railroads. The Confederates began a series of small-scale attacks, keeping up nearly constant harassment. Halleck, cautious by nature, established an elaborate procedure to protect his army as they advanced. As the troops moved up to a new position, they dug trenches day and night. These “were made to conform to the ground’s nature, following the ridges’ crest… They consisted of a single ditch and a parapet… only designed to cover our infantry against the enemy’s projectiles.” As each line of earthworks was finished, the men advanced about a mile and started digging a new line of trenches. Eventually, there were seven progressive lines and about 40 miles of trenches. Their work was described as the “most extraordinary display of entrenchment under offensive conditions witnessed in the entire war.”

The Confederates waiting in Corinth were well aware of Halleck’s slow but constant advance. In May, a Confederate soldier wrote his wife:

“I can sit now in my tent and hear the drums and voices in the enemy lines, which cannot be more than two miles distant. We have… killed and wounded every day… The Yanks are making heavy preparations for the attack, which I think cannot be postponed many days longer… Everything betokens an early engagement, so make it be, for I am more than anxious that it shall come without further delay.”

On May 21, General Beauregard planned a counterattack, an attempt to “draw the enemy out of its entrenched positions and separate his closed masses for a battle.” The gamble came to naught because of delays in getting the troops in position to attack.

By May 25, the long Union line was entrenched on high ground within a few thousand yards of the Confederate fortifications. From that range, Union guns shelled the Confederate defensive earthworks and the supply base and railroad facilities in Corinth. Beauregard was outnumbered two to one. The water was bad. Typhoid and dysentery had felled thousands of his men. At a council of war, the Confederate officers concluded they could not hold the railroad crossover.

Beauregard saved his army by a hoax. Some men were given three days’ rations and ordered to prepare for an attack. As expected, one or two went to the Union with that news. During the night of May 29, the Confederate army moved out. They used the Mobile and Ohio Railroad to carry the sick and wounded the heavy artillery, and tons of supplies. When a train arrived, the troops cheered as though reinforcements were arriving. They set up dummy guns along the defensive earthworks. Campfires were kept burning, and buglers and drummers played. The rest of the men slipped away undetected. When Union patrols entered Corinth on the morning of May 30, they found the Confederates gone.

During the siege, there were some 120,000 Union troops and 70,000 Confederate troops engaged. Each side had estimated casualties of about 1,000 men. Most historians believe that the Union seizure of the strategic railroad crossover at Corinth led directly to the fall of Fort Pillow, Tennessee, on the Mississippi River, the loss of much of Middle and West Tennessee, the surrender of Memphis, and the opening of the lower Mississippi River to Federal gunboats as far south as Vicksburg. No Confederate train ever again carried men and supplies from Chattanooga to Memphis.

The Battle of Corinth

After the Confederates evacuated Corinth, Union soldiers occupied the town. They spent most of the long, hot summer digging wells to find good water and building additional fortifications. General Halleck ordered the construction of a series of more extensive earthwork fortifications called “batteries,” designed to hold cannons to protect Corinth against Confederate forces approaching from the South. Major General William S. Rosecrans concentrated on protecting the railroad crossover and its vital supplies. He immediately built an inner series of batteries on the ridges around the town. Trenches for infantrymen connected the batteries, and masses of sharpened logs pointing outward (the Civil War equivalent of barbed wire) strengthened the line.

The military situation changed dramatically in the summer and early fall of 1862. The South seized the initiative from Virginia to the Mississippi River and beyond. In hard-fought battles, the Confederates carried the fighting to the North. On the all-important diplomatic front, the British government seemed on the verge of recognizing the Confederacy as an independent country.

In September, many of the men at Corinth went off to fight a bloody battle at Iuka, Mississippi, successfully blocking a Confederate move into middle Tennessee. On October 2, General Rosecrans learned that the Confederates were approaching from the northwest. The two armies each had 22,000-23,000 men, but Rosecrans’ position behind his defensive earthworks was strong. He stationed his advance guard about three miles beyond the town limits. On October 3, Union and Confederate forces clashed initially in the area fronting the old Confederate earthworks. In heavy fighting throughout the day, the Confederates pushed Union forces back about two miles. Confederate Major General Earl Van Dorn, sure he could win an overwhelming victory in the morning, called a halt to the fighting at about 6:00 p.m. Parched and exhausted from lack of water and 90-degree heat, his troops camped for the night, some only a few hundred yards from the inner fortifications where Union troops had taken refuge.

During the night, Union commanders moved their men into a more compact position closer to Corinth, covering the western and northern approaches to the community. The partially entrenched line was less than two miles long and was strengthened at key points by the cannons of the batteries named Tannrath, Lothrop, and Phillips located on College Hill southwest of the town; batteries Williams and Robinett, positioned overlooking the cut of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad immediately west of the rail junction; and an unfinished Battery Powell, still being built on the northern outskirts of Corinth.

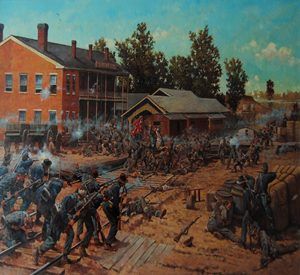

Before dawn on October 4, the Confederates woke the Union troops with artillery fire, but things quickly began to go wrong. The general who was to lead the opening attack had to be replaced, causing confusion and delay. But, at about 9:00 a.m., the Confederates opened a savage attack on the Union line. Some of the Confederates fought their way into the town. Battery Powell changed hands twice in fierce fighting. At about 10:00 a.m., four columns of gray-clad Confederates advanced on Battery Robinett. The men inside the battery watched them come, one describing it:

“As soon as they were ready, they started at us with a firm, slow, steady step. In my campaigning, I had never seen anything so hard to stand as that slow, steady tramp. A sound was not heard, but they looked as if they intended to walk over us. I afterward stood a bayonet charge… that was not so trying on the nerves as that steady, solemn advance.”

A man from an Alabama regiment described the scene from the Confederate side:

“The whole of Corinth, with its enormous fortifications, burst upon our view. The United States flag was floating over the forts and in town. A perfect storm of grapeshot, canisters, cannonballs, and mini-balls met us. Oh God! I have never seen the like! The men fell like grass.”

Four times, they charged, each time being mowed down by withering fire from the cannons of batteries Robinett and Williams and the muskets of the men lined up in the field next to the batteries. After desperate fighting, a Union bayonet charge broke the enemy columns and drove them back. By noon, Van Dorn’s army was in retreat. Rosecrans did not pursue the retreating army until the next day, and eventually, Van Dorn managed to save his army. Some 23,000 Union soldiers engaged during the battle, resulting in 2,359 casualties. Of the Confederate Army, some 21,000 soldiers were involved, resulting in 4,388 casualties. Union victories at Corinth, Antietam, Maryland, and Perryville, Kentucky, set the stage for Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and helped prevent the British and the French from recognizing the Confederacy. The Confederacy never recovered from its losses in September and October 1862.

The struggle over Corinth and its railroad crossroads would continue for six months.

The Union continued to occupy Corinth for the next 15 months, using it as a base to raid northern Mississippi, Alabama, and southern Tennessee. Control of Corinth and its railroads opened the way for Union victory at Vicksburg, Mississippi, in July 1863. On January 25, 1864, Union troops left the town. The Confederates returned, but it was too South. The South had not built a single locomotive since 1861 and could no longer use the once critical railroad lines. Mules pulled the only cars moving on the patched-together tracks.

Today, the Corinth Battlefield Unit contains numerous historic sites associated with the city’s siege, battle, and occupation during the Civil War. Several miles of rifle pits, trenches, artillery positions, and the earthworks of Batteries F and Robinett still exist. Located near the site of Battery Robinett, the Corinth Civil War Interpretive Center is open from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. every day except December 25. The center exhibits include interactive displays and multimedia presentations on the Battle of Shiloh, the Siege, and the Battle of Corinth. Elsewhere, the historic depot houses a museum, the National Cemetery, the Contraband Camp, historic homes where officers were housed, and more can be found.

Civil War Trail guides are available at several locations throughout Corinth: the Corinth Civil War Interpretive Center, the Mississippi Welcome Center, and the Crossroads Museum at the Historic Corinth Depot. The museum also offers a free CD that narrates the tour.

Historic Civil War Sites:

1. Corinth Civil War Interpretive Center at Battery Robinett – This National Park Service Visitor Center is a unique experience of informative exhibits, two films, and an interpretive courtyard water display. The Interpretive Center is located at the site of Battery Robinett, an earthen redoubt that was a key position in the fighting on October 4, 1862. Open daily, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Closed Christmas. Free admission. 662-287-9273.

2. Trailhead Park – The strategic crossing of the historic Memphis & Charleston and Mobile & Ohio Railroads was extremely important to the Confederacy and the Union since this was the only crossing of two standard-gauge railroads in the Confederacy. W. Waldron Street.

3. Crossroads Museum at the Historic Corinth Depot exhibits Civil War artifacts and 20th-century memorabilia. Tuesday-Saturday, 10 a.m.-4 p.m., closed major holidays, 221 North Fillmore Street, Corinth, Mississippi 38834, 662-287-3120. Admission fee.

4. Corinth National Cemetery – Established in 1866, the Corinth National Cemetery is the final resting place for 5,700 Union soldiers who died in the capture and occupation of Corinth and other engagements in Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. The first interments were gathered from a dozen sites throughout the three states. Three Confederate burials are also in the cemetery, including one unknown and two known soldiers. Corinth National Cemetery’s layout is square, bisected by a central avenue running from the southern main gate to a rear gate on the north end of the property. Double gates at the northern and southern entrances are ornamental wrought iron supported by granite piers and flanked by narrower pedestrian gates. At the cemetery’s north end, the central avenue splits around a grassy circle on which the cemetery’s flagpole is located. A series of parallel east-west avenues further divide the cemetery into smaller burial sections. A brick wall constructed in 1878 to replace a wooden picket fence encloses the cemetery. This is the final resting place for 1,793 known and 3,895 unknown Civil War soldiers representing 273 regiments from 15 states. The two-acre site is located at 1551 Horton St. and is open for daily visitation from 8:00 a.m. to sunset; however, no cemetery staff is on site. Corinth National Cemetery and other sites associated with the Battle of Corinth are National Historic Landmarks.

5. Corinth Contraband Camp – This is the site of the model camp established for runaway slaves. At its peak, as many as 6,000 people were thought to have resided here. As Federal forces occupied major ports in the South, slaves escaped from farms and plantations and fled to safety behind Union lines. Once President Abraham Lincoln’s Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was issued in September 1862, freedom seekers increased considerably in Union-occupied Corinth.

Union General Grenville M. Dodge established the Corinth Contraband Camp to accommodate these refugees. The camp featured numerous homes, a church, a school, and a hospital. The freedmen cultivated and sold cotton and vegetables in a progressive cooperative farm program. By May 1863, the camp was making a profit of $4,000 to $5,000 from its enterprises. By August, over 1,000 African American children and adults had gained the ability to read through the efforts of various benevolent organizations. Although the camp had a modest beginning, it became a model camp, allowing approximately 6,000 ex-slaves to establish their identities.

Once the Emancipation Proclamation was implemented, nearly 2,000 newly freed men at the Corinth Contraband Camp had their first opportunity to protect their way of life. They made up a new regiment in the Union army. Since most men came from Alabama, the unit was named the 1st Alabama Infantry Regiment of African Descent, later re-designating the 55th United States Colored Troops. In December 1863, the camp was moved to Memphis, Tennessee, and the freedmen resided in a more traditional refugee facility for the remainder of the war. The Corinth Contraband Camp was the first step on the road to freedom and the struggle for equality for thousands of former slaves.

Today, a portion of the historic Corinth Contraband Camp is preserved to commemorate those who began their journey to freedom there in 1862-1863. This land now hosts a quarter-mile walkway that exhibits six life-size bronze sculptures depicting the men, women, and children who inhabited the camp.

6. Fish Pond House – This home was the headquarters for Confederate Generals P.G.T. Beauregard and John Breckinridge.

7. Union Siege Line May 33, 1862) – This section of earthworks was used until May 17, when the next line was constructed.

8. Farmington Baptist Church – Skirmishes were fought in this area between May 100 and May 22, 1862. Several Confederate soldiers are buried in the cemetery.

9. Union Siege Line May 177, 1862) – Union troops manned this line until May 28.

10. Union Siege Line May 199, 1862) – Used for one week. This line was abandoned and moved forward on May 28.

11. Union Siege Line May 288, 1862) – This line was used until the siege ended on May 30.

12. Beauregard Line – This site is part of 7 ½ miles of Confederate earthworks constructed before and during the Siege of Corinth. Union troops later used them as a defensive line during the October 1862 Battle of Corinth.

13. Battery Powell – This is the site of a Federal Battery that was briefly overrun by Confederate troops during the Battle of Corinth on October 4, 1862.

14. Oak Home – This home served as the headquarters for Confederate General Leonidas Polk.

15. Rose Cottage – Once at this location, the home served as headquarters for Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston.

16. Verandah/Curlee House Museum – Completed in the spring of 1857, the Verandah House was built for one of the two founders of Corinth, Hamilton Mask. The house is a significant example of Greek Revival architecture. As a result of the crossroads of the two standard-gauge railroads in Corinth, the area became of prime importance to the Union and Confederacy. On the evening of April 22, 1862, General Albert Sidney Johnston met with General Braxton Bragg in his bedchambers at the Verandah House to officially sign Order No. 8 to launch the Confederate counter-offensive against the Union army that ended in the Battle of Shiloh, April 6-7, 1862. Throughout the war, generals from both the Confederacy and the Union were quartered in this house. Following the war, the Corinth Female Academy occupied the building briefly. It was then purchased by William Peyton Curlee, one of the founders of the Curlee Clothing Company. After Mr. Curlee’s death from yellow fever, Mrs. Curlee, a descendant of Daniel Boone, sold the house to Leroy Montgomery, who raised a large family in the home. In 1921, Shelby Hammond Curlee, the oldest son of the previous Curlee owners, bought the house. The descendants of the Curlee family donated the house to the city in 1961. 301 Childs Street, Corinth, Mississippi, 662-287-9501.

17. Mitchell House -This site was home to the home that served as headquarters to Union Generals Ulysses S. Grant, Grenville Dodge, and Confederate General James Chalmers.

18. Duncan House – This home was the headquarters for Confederate Generals P.G.T. Beauregard, John Breckinridge, and Union General W.S. Rosecrans.

19. Corona College Site – Corona Female College was a female seminary founded in 1857. It was situated in a three-story building. The Union Army commandeered its main building for use as a hospital during the nearby battle of Shiloh in 1862. The Union Army evacuated the area in 1864, burning the college’s building. Corona Female College never reopened.

20. Federal Redan – The earthen fort that guarded the road from Kossuth was located at this site.

21. Battery F – One of six forts built by the Union Army comprising the “Halleck Line,” this battery witnessed heavy fighting on October 3, 1862.

22. Alcorn County Courthouse – Built in 1917, it is the seat of government for Alcorn County. Two Civil War-related monuments are on the grounds.

More Information:

Corinth, Mississippi Civil War

Corinth Area Convention & Visitors Bureau

215 N. Fillmore St.

Corinth, Mississippi 38834

662-287-8300 or 800-748-9048

All historic sites, including the Davis Bridge Battlefield 18 miles northwest of Corinth near Pocahontas, Tennessee, are accessible by automobile.

After four long years of occupation during the Civil War, the Union finally left Corinth in January 1864. During those years, as many as 300,000 soldiers from both the North and South passed through the area, leaving behind devastation. Though war-torn and ravaged, Corinth forged onward. After recovering and rebuilding, a period of rapid growth occurred, and in 1870, Tishomingo County was divided into three counties: Alcorn, Prentiss, and Tishomingo. Corinth became the Alcorn County seat.

The James-Younger Gang – Left to right: Cole” Younger, Jesse Woodson James, Bob Younger, and Frank James.

Reconstruction officially ended in 1875, and Corinth continued to flourish. During these years of growth, someone else took notice of Corinth’s prosperity- outlaws. On December 7, 1874, four armed men robbed the Tishomingo Savings Bank of $5000 in cash and $5,000 worth of jewelry. Thought to have been none other than the James-Younger Gang from Missouri, a Corinth newspaper reported:

“Four well-mounted men rode up to the Tishomingo Savings Bank; two entered and locked the door, and two remained outside. They demanded the safe keys, which President Taylor refused. They then made an attack on him with knives and compelled him to submit. They took over five thousand dollars in currency and watches and diamonds. Mr. Taylor was not badly hurt. A negro man was in the bank depositing at the time and was not permitted to leave until the robbers retired. They were in the bank for about 15 minutes… The men had been lurking about the town and country for two weeks. The robbers fired several shots as they started and rode in the direction of the Tennessee River.”

Over the following years, the city developed several cultural and recreational venues, including an Opera House, the Henry Moore Museum, Mooreville Zoological Park, and the Coliseum, which still stands today. It also drew several manufacturing companies, mills, and factories. In December 1924, Corinth’s downtown district was devastated by a terrible fire. After more than six hours of fighting in bitterly cold weather, the fire department confined the blaze to a single block. However, the blaze destroyed over 30 stores, resulting in more than $1,500,000 in losses. The buildings destroyed were the post office, a jewelry store, the opera house, the Corinth Bank and Trust Co., a merchandise store, and the Ford Museum.

Today, Corinth is often called Mississippi’s Gateway City due to its location in the state’s northeast corner. In addition to its many Civil War sites, Corinth provides several other historical attractions that are well worth a visit.

Other historical attractions include the Black History Museum of Corinth, several historic businesses, the Coca-Cola Museum, the Coliseum Theater, and much more.

More Corinth Area Attractions:

Black History Museum of Corinth – Displays memorabilia and artifacts relating to the history of Corinth’s African American residents, emphasizing education and religion. Collections include tributes to Corinth’s first black Mayor, Mayor E.S. Bishop; entertainers such as opera singer Ruby Elzy; local and nationally known sports figures; African art and artifacts; and artifacts from local historically black churches and former segregated black schools. 1109 Meigg Street, 662-665-8500.

Coca-Cola Museum – The story of Coca-Cola has enthralled people since its beginning in 1886. Thousands of people collect, buy, sell, and swap almost every article stamped with the famous Coca-Cola trademark. In 1905, Avon Kenneth Weaver bought an interest in the Corinth Bottle Works, a small soda water plant. At that time, Coca-Cola was produced in Jackson, Tennessee, and shipped by rail to Corinth. Mr. Weaver obtained a Coca-Cola franchise for Northeast Mississippi in 1907. The same family still owns the company. The exhibits in the museum include historical images, artifacts from the past 100 years, and interactive computer stations with information about the 100 years of Corinth Coca-Cola. 305 Waldron Street, Corinth, Mississippi 662-284-4848.

The Coliseum Theater – Benjamin Franklin Liddon, a local banker and civic leader, designed and constructed the Coliseum Theater in 1924 with a capacity of 999 seats. The theater is a showplace of Victorian and Art Deco Design. Such elements as black and white tile, ornamental plaster on the ceilings, imported white marble wainscoting, and a grand staircase warrant its inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. It is also a Mississippi Landmark. Originally designed as a palatial multi-purpose theatre, the Coliseum accommodates live and screen performances in its acoustically perfect auditorium. Traveling Vaudeville Shows came to Corinth by rail to perform in the Coliseum. Child stars often performed here and later became nationally known as adult actors. During the early days of the movie industry, a theatre organ in the orchestra pit accompanied the silent screen performances on a screen dropped from the fly area over the stage. Later, “Talkies” arrived, and traveling performances by musicians from the Grand Ole Opry, the rock and roll of the Elvis Presley era, and others became part of the Coliseum’s rich repertoire. In more recent years, the Coliseum was the most visited movie theatre in the area and, since 1981, has served the Corinth and Alcorn County area as a civic and performing arts center for a myriad of events among diverse groups. Open for tours by appointment, 404 Taylor Street, Corinth, Mississippi 38835, 662-284-7440.

Historic Downtown Corinth:

Biggers Hardware – This hardware store opened its doors in 1918 and has been a mainstay in the community ever since. The store’s ownership is in the fourth generation of the Biggers family.

Borroums Drug Store – Founded in 1865 by former CSA army surgeon A.J. Borroum, this is the oldest drug store in continuous operation in Mississippi. It houses Native American artifacts, Civil War relics, and an authentic, working soda fountain. This business has been owned and operated by the Borroum family since its founding. One specialty of the diner part of the soda fountain is a local favorite called a slugburger. Slugburgers are a Depression-era “burger” of meat, breading, or soy meal. There’s even a Slugburger Festival every year to celebrate this local delicacy.

Waits Jewelry and Fine Gifts – The oldest business in Corinth, dating from 1865. The store’s second generation of ownership was Earnest J. Waits, a true “renaissance man.” Not only was he a watchmaker and jeweler, but he also constructed an airplane from plans in Popular Mechanics, and its flights in Corinth were the first in Mississippi and probably in the Deep South. He built an early wireless telegraph and an X-ray machine and painted beautiful seasonal murals in the building. A small area of the store is dedicated to him and his wife Eugenia, the last family member to own the Store in 2004.

For those interested in venturing beyond Corinth into Alcorn County, visit the Jacinto Courthouse, located off Hwy 356, approximately eight miles east of Rienzi. Completed in 1854, the two-story federal-style courthouse tells a compelling story of the bygone glory days of a bustling southern boomtown. Rienzi itself is interesting in its way. Although not a ghost town, supporting about 300 people, most of its business buildings are reminiscent of a ghost town, testifying that Rienzi’s heyday has faded. Rienzi was also a very active site during the Civil War activities in Corinth.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2025.

Also See:

Civil War Battles of Mississippi

Mississippi – The Magnolia State

Pick & Shovel Warfare in the Civil War

See Sources.