The Fastest Time on Record by A.J. Yates, May 10, 1893, when Engine 999, drawing the Empire State Express train, made the record of 112.5 miles an hour.

By John Moody in 1919

In 1862, the United States Government granted a charter to construct a railroad from Omaha, Nebraska, to the Pacific coast. At that time, Iowa and Missouri were the only states west of the Mississippi Valley where any railroad construction of importance existed.

During the three decades that had passed since the first railroad construction, the earlier transportation methods by boat, canal, and stagecoach gave way to more modern transportation methods in the Eastern half of the United States. As a result of these new conditions, the states, cities, and towns were welded together. Population and prosperity increased rapidly in those inland sections that had formerly languished because they had no means of easy and rapid communication.

However, the construction of extensive railways, particularly the consolidation of small, experimental lines into large systems, dates from the days of the discovery of gold in California. The nation did not begin to realize the extraordinary possibilities of the vast Western territory until its attention was thus suddenly. Definitely, it concentrated on the Pacific by the annual addition of over fifty million dollars to the circulating medium.

The wealth drawn so copiously from this Western part of our continent stimulated the commerce, manufacturing, and trade of the entire Eastern section. People began to understand that with the acquisition of California, the nation had obtained practically half a continent, of which the future possibilities were almost unlimited so far as the development of natural resources and the general production of wealth were concerned.

The public conviction that a railroad linking the West and the East was an absolute necessity became so pronounced after the gold discoveries of ’49 that Congress passed an act in 1853 to survey several lines from the Mississippi River to the Pacific. Though the published reports of these surveys threw a flood of light on the continent’s interior, they led to no definite result at the time because the rivalry of sections and groups of interests for selecting this or that route held up all progress.

The Act of 1862, which created the Union Pacific Railroad Company, together with the amending Act of 1864, authorized the construction of a mainline from an initial point “on the one-hundredth meridian of longitude,” in the Territory of Nebraska to the eastern boundary of California, with branch lines to be constructed by other companies and to radiate from this initial point to Sioux City, to Omaha, to St. Joseph, to Leavenworth, and to Kansas City.* Provision was made for a subsidy of $16,000 a mile for the level country east of the Rocky Mountains, $48,000 a mile for the lines through mountain ranges, and $32,000 a mile for the section between the ranges. The original plan to secure the government subsidies by a first mortgage on the lines was amended to allow private capital to take the first mortgage and the Government to take a second lien for its advances. In addition to these subsidies, several companies were to receive land grants of 12,800 acres to the mile in alternate sections contiguous to their lines. Upon the same terms, the Central Pacific Railroad, a company incorporated under the laws of California, was authorized to construct a line from the Pacific coast, at or near San Francisco, to meet the Union Pacific Railroad.

The Act of 1862, which created the Union Pacific Railroad Company, together with the amending Act of 1864, authorized the construction of a mainline from an initial point “on the one-hundredth meridian of longitude,” in the Territory of Nebraska to the eastern boundary of California, with branch lines to be constructed by other companies and to radiate from this initial point to Sioux City, to Omaha, to St. Joseph, to Leavenworth, and to Kansas City.* Provision was made for a subsidy of $16,000 a mile for the level country east of the Rocky Mountains, $48,000 a mile for the lines through mountain ranges, and $32,000 a mile for the section between the ranges. The original plan to secure the government subsidies by a first mortgage on the lines was amended to allow private capital to take the first mortgage and the Government to take a second lien for its advances. In addition to these subsidies, several companies were to receive land grants of 12,800 acres to the mile in alternate sections contiguous to their lines. Upon the same terms, the Central Pacific Railroad, a company incorporated under the laws of California, was authorized to construct a line from the Pacific coast, at or near San Francisco, to meet the Union Pacific Railroad.

* These ambitious designs were never fully realized. The mainline ran eventually west from Omaha, meeting the Sioux City branch at Fremont. The only other branch constructed to connect with the Union Pacific was that from Kansas City, which ran first to Denver.

The public was quick to realize the significance of this huge enterprise, for the newspapers of the day were full of such comments as the following:

“It is useless to enlarge upon the value and importance of this great work. It concerns not the United States alone but all mankind. Its line is coincident with the natural and convenient route of commerce for the world… Over it, the trip will be made from London to Hong Kong in forty days, over a route possessing every comfort and attraction, which takes a continent in its course, and which, from the variety and magnitude of its sources, from the race which now dominates it, and from the extent of their numbers, wealth and productions, must soon give law to the commercial world.”

Although the Government had liberally subsidized the construction, gross extravagance had promptly crept in; the juggling of accounts to secure profits on the government advances was freely indulged in, and after only a small section of the line had been completed, it was announced that more capital must be forthcoming or the work would cease.

Notwithstanding these and similarly optimistic sentiments, the meager financial support given to the enterprise by the public at Out of this situation grew the plan for subletting the work to a construction company known as the Pennsylvania Fiscal Agency–a name which was afterward changed to that of the Credit Mobilier of America. With its irregularities involving conspicuous politicians, the story of the Credit Mobilier is one of the most disgraceful in American history. The detailed history of these operations need not be considered here; it is sufficient to say that, finally, despite political scandals, the Union Pacific lines were completed. Within two years after the letting of the contracts to this new company, in 1866, over five hundred miles of road were completed and in operation. An advertisement published late in 1868 announced that “five hundred and forty miles of the Union Pacific Railroad, running west from Omaha across the continent, are now completed, the track being laid and trains running within ten miles of the Rocky Mountains… The prospect that the whole grand line to the Pacific will be completed by 1870 was never better.”

As a matter of fact, the line through to the coast was finished earlier than was predicted. One fact which increased the rapidity of construction was the growing financial difficulty of the company. It was absolutely imperative that the through-line be completed so that the resulting business might make the operation of trains pay. But aside from this, another influence was at work to encourage rapid construction. The Act of 1862 provided that the Central Pacific Railroad might also build across Nevada to meet the Union Pacific on the condition that it completed its allotted section first. As the Central Pacific also was receiving a heavy government subsidy per mile, and as there was great profit in construction undertaken with this government subsidy, there was naturally a strong incentive for both companies to build all the mileage possible and as rapidly as possible.

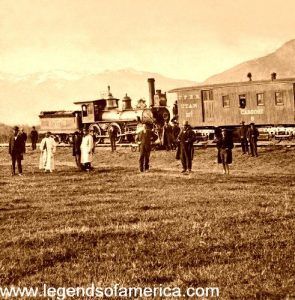

The Central Pacific enterprise was backed by a group of men who were awake to the possibilities of the situation and made large fortunes in the gold-mining boom of previous years, such as Leland Stanford, Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and the Crockers.

The rivalry between them and the Union Pacific interests woke the whole continent. It formed a chapter in American railroad history as startling and romantic as anything in the stories of the Vanderbilts and Goulds with their financial gymnastics.

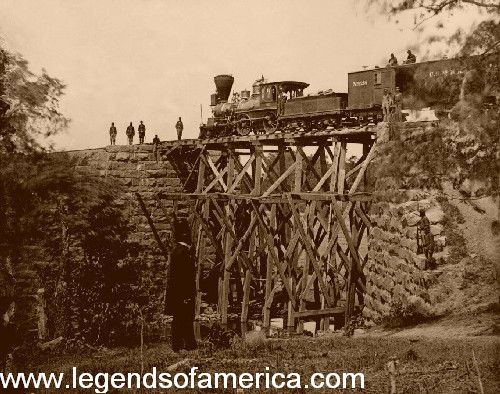

As the contest proceeded, public interest increased, and the entire country watched to see which company would win the big government subsidies through the mountains. Through the winter of 1868, the work continued on the Union Pacific with unabated energy, and freezing weather caught the builders at the base of the Wasatch Mountains, but blizzards could not stop them. The workmen laid tracks across the Wasatch range on a bed of snow and ice, and one of the track-laying trains slid bodily, track and all, off the ice into a stream. The two companies had over 20,000 men at work that winter. Suddenly, the Central Pacific Railroad surprised the Eastern builders by filing a map and plans for building as far as Echo, Nevada, some distance east of Ogden. The Union Pacific forces, however, were equal to the occasion. At first, one mile a day had been considered rapid construction. Still, even with the limited daylight of the winter months, they were laying over two miles a day, and they finally crowned their efforts by laying nearly eight miles of track in one day between sunrise and sunset.

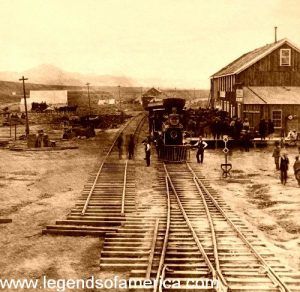

In the meantime, the Central Pacific Railroad also had stopped at nothing. The company had a dozen tunnels to build but did not wait to finish them. Supplies were hauled over the Sierras, and the work was pushed ahead regardless of expense. On May 10, 1869, the junction was formed, the opposing track layers meeting at Promontory Point, fifty miles west of Ogden, Utah. Spikes of gold and silver were driven into the joining tracks, and the through-line from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean had been completed; the first engine from the Pacific coast faced the first engine from the Atlantic. The whole country celebrated this achievement, from President Grant in the White House to the newsboy who sold extras. Chicago held a parade several miles long; in New York City, the chimes of Trinity were rung, and in Philadelphia, the old Liberty Bell in Independence Hall was tolled again.

The cost of the Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha to its junction with the Central Pacific Railroad formed a controversy for a generation. The saving of six months of the allotted time for completing the road no doubt increased its cost to the builders, for they sometimes borrowed money in the East at rates as high as 18 and 19 percent. Besides, in pushing the line far beyond the bounds of civilization without waiting for the slower pace of the settler and the security that his protection afforded, it often became necessary for half the total number of workmen to stand guard and thus reduce the working capacity of the construction force. Even so, hundreds were killed by the Indians.

Governmental restrictions of various kinds also increased the cost of the road. For example, the stipulation that only American iron should be used increased the cost by at least ten dollars for every ton of rail laid. The requirement that a cut should be made through each rise in the Laramie plains, thus giving the track a dead level instead of conforming to the natural roll of the country, ultimately resulting in a waste of from five to ten million dollars.

Extraordinary costs such as these, combined with the extravagant methods of construction and financing, brought the total cost of the property up to what was in those days a fabulous sum of money. The records indicate that the profits which accrued through the Credit Mobilier and in other ways in the construction up to the time of the opening in 1869 exceeded 50 million dollars.

While the Union Pacific was being built, from 1862 to 1869, other railroads were not idle, and many were rapidly reaching out into the Central West. Not only had the Chicago and North Western reached Omaha and connected with the Union Pacific, but the Kansas Pacific Railroad had penetrated as far west as Denver and joined the Union Pacific at Cheyenne, Wyoming.

The close relationship between railroad expansion and the general development and prosperity of the country is nowhere brought more distinctly into relief than in connection with the construction of the Pacific railroads. With the opening of a transcontinental line, the vast El Dorado of the West was laid practically at the doorstep of the Eastern capital. Not only did American pioneers definitely turn toward the West, but foreign emigrants bent their steps in vast numbers in that direction, and capital in steadily increasing amounts made its way there. Towns sprang up everywhere and soon developed into busy centers of trade and commerce.

Caravan trains, which had followed a single westward line a few years before, now started from points along the railroad artery and penetrated far to the north and south. The settlers knew that the time was not far distant when all the vast territory west of the Missouri River, from the Canadian border to the Rio Grande, would be reached by the rapid spread of the railroad.

In the sixties and seventies, there sprang up and rapidly developed in size and importance such centers as Kansas City, Sioux City, Denver, Salt Lake City, Cheyenne, Atchison, Topeka, Helena, Portland, Seattle, Duluth, St. Paul, Minneapolis, and scores of smaller places. The entire Pacific slope was soon dotted with towns and cities, and even the great arid plains of the West–as well as the “Great American Desert” covering Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Nevada — began to take on signs of life which had not been dreamed of a decade before.

But the development of this great section of the country during the next few years was even more notable. By 1880, four different railroad lines were running through the Pacific States, and a fifth, the Denver & Rio Grande, had penetrated through the mountains of Colorado and across Utah to the Great Salt Lake. These were the years when the modern industrial era was really beginning. Man’s viewpoint was changing, and instead of remaining content with the material achievements of the Atlantic and Central sections of the continent, he began to realize that the vast Western regions and the thousand miles of Pacific coastline were destined to be America’s inexhaustible patrimony for the years to come.

In 1880, the Union Pacific began its expansion to the eastward and acquired control of the Kansas Pacific, which had come upon evil days, and of the Denver Pacific, a most important connecting link. In January 1880, these two companies were absorbed by the Union Pacific, thus obtaining a continuous line from St. Louis westward. In the meantime, the Central Pacific, operating from Ogden west to the coast, had added many branches. At the same time, a new company–known as the Southern Pacific Railroad of California — had for some years been constructing a system of lines throughout that State south of the Central Pacific and by 1877 had penetrated Yuma, Arizona, 727 miles southeast of San Francisco. It had also built lines into Arizona and New Mexico and soon joined the Santa Fe route, which had for some time been working westward.

In 1881 the Southern Pacific continued its eastern extensions along the Rio Grande to El Paso, Texas, where it connected with a new road under construction from New Orleans. A junction was also made at El Paso with the Mexican Central, which was under construction to the City of Mexico.

The Southern Pacific Railroad was closely allied with the Central Pacific interests headed by Collis P. Huntington. In 1884, the great Southern Pacific Company was formed, which acquired stock control of the entire aggregation of railroads in the South and Southwest. At the same time, the Central Pacific came under the direct control of the Southern Pacific through a long lease.

During these eventful years, while the Southern Pacific properties were penetrating eastward through the broad stretches of the country to the south of the Union Pacific lines, equally interesting events were occurring in the north. In 1879, the Oregon Steamship and Navigation Company was consolidated, with several short railway lines in Oregon and Washington, under the name of the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company.

These railroad lines extended east from Portland to the Oregon state line and north to Spokane, finally connecting with the new Northern Pacific. At the same time, another road, known as the Oregon Short Line Railroad, was built from Granger, Wyoming, on the line of the Union Pacific to a junction with the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company at Huntington, Oregon, on the Snake River. The Oregon Short Line came under the control of the Union Pacific and was opened for traffic in 1881. Later a close alliance was made with Henry Villard, the controlling spirit in the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company. Ultimately, the entire system of Oregon lines passed under Union Pacific control, to be lost in the receivership of 1893, but it was later recovered under the Harriman regime.

When, after ten more years of expansion, the great Union Pacific property went into the hands of receivers in 1893, it had grown to a system of more than 8,000 miles. It completely controlled the Oregon railway and steamship lines, the lines to St. Louis, and also an important extension known as the Union Pacific, Denver, and Gulf Railroad, running from a point in Wyoming across Colorado to Fort Worth, Texas. The financial failure of the system was due to a variety of causes. Its management had been extravagant and inefficient, and construction and expansion had been too rapid. The policy of building expensive branch lines where they were not needed and of obligating the parent company to finance them had been a grievous mistake and had contributed largely to the company’s downfall.

Further than this, the credit of the Union Pacific was steadily growing weaker because the time was drawing near when its heavy debt to the United States Government would fall due. In its more than 20 years, the company had never paid any interest in government debt, nor had it maintained a sinking fund to meet the principal when due. Consequently, the accruing interest had mounted year by year, and should the Government enforce payment at maturity in 1897-99, the company would be doomed to bankruptcy. This government debt, including accrued interest, amounted to the sum of $54,000,000.

Attention should not be diverted from the fact that during all these years, a vast expansion of competitive lines had been going on far southward of the Union Pacific. Under the guiding genius of Collis P. Huntington, the Southern Pacific Company in 1884 had consolidated and solidified a gigantic system of railways extending from New Orleans to the Pacific and throughout the entire State of California to Portland, Oregon, with branch lines radiating through Texas and making close connection with roads entering St. Louis. In addition to these railroads, Huntington acquired control of a steamship line operating from New York to New Orleans and Galveston, and subsequently of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, operating along the coast from Oregon south to the Isthmus of Panama and across the Pacific Ocean.

The ever-growing effects of this powerful and well-managed competitor–combined with the large development of the Santa Fe system during these years, the competition of the completed Northern Pacific, and the possibilities of the new Great Northern Railway or Hill line, now completing its main artery to the Pacific–were far-reaching enough in themselves to bring the Union Pacific upon evil days. Consequently, few were surprised when, under the great pressure of the panic of 1893, the property was forced to confess insolvency.

The Union Pacific had simply repeated the story of most American railroads; it had been constructed in advance of population and had to pay the penalty. Yet, it had more than justified the hopes of the daring spirits who projected it. It may have made individuals bankrupt, but it magnificently fulfilled the part that it was expected to play. It had opened up millions of acres to cultivation, given homesteads to millions of people, many of whom were immigrants from Europe, developed mineral lands of incalculable value, created several new great States, and made the American nation a unified whole. Its subsequent history belongs to another chapter of this story–a history that is richer than the first in the matter of financial success, but that can never surpass the early pioneering years in real and permanent achievement.

By John Moody, 1919. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

About the Author: John Moody wrote The Railroad Builders, A Chronicle of the Welding of the States in 1919. A Century of Railroad Building is the first chapter of the book. Though the content remains essentially original, it has been edited for grammar, spelling, and ease for the modern reader.

Also See: