“This nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'”

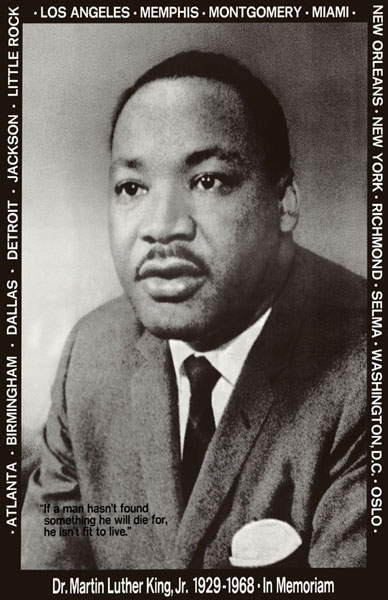

Martin Luther King, Jr. was a Baptist minister and equal rights activist who was the most visible spokesperson and leader of the American Civil Rights Movement from the mid-1950s until his assassination in 1968. He is best known for advancing Civil Rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience, inspired by his Christian beliefs and nonviolent activism.

King sought equality and human rights for African Americans, as well as helping people experiencing poverty and others who were victims of injustice through peaceful protest. He was the driving force behind important events such as the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott and the 1963 March on Washington, which helped bring about new legislation such as the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 and is remembered each year on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, a U.S. federal holiday since 1986.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, to Martin Luther King Sr., a pastor, and Alberta Williams King, a former schoolteacher. Coming from a long line of Baptist ministers, he spent his boyhood in a home in the city’s Sweet Auburn neighborhood that his parents shared with his maternal grandparents. This area was one of the country’s most prominent and prosperous African American neighborhoods.

His grandfather, the Reverend Adam Daniel Williams, began the family’s long tenure as pastors of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, serving from 1914 to 1931. Afterward, his father served the church for the next four decades, with Martin Luther, Jr acting as co-pastor in the 1960s.

King attended segregated public schools where he excelled and graduated from high school at the age of 15. In 1944, he was admitted to Morehouse College, where both his father and maternal grandfather attended, and he studied medicine and law. After graduating in 1948, he attended the Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, for three years. He was elected president of a predominantly white senior class and was awarded a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1951.

With a fellowship he won at Crozer, he enrolled in graduate studies at Boston University and received his doctorate in 1955. While there, he met Coretta Scott, a young singer from Alabama who was studying at the New England Conservatory of Music. The couple married on June 18, 1953, and eventually had two sons and two daughters. Afterward, they settled in Montgomery, Alabama, where King became the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church pastor in 1954.

By then, he was a member of the executive committee and an active participant in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the leading organization of its kind in the nation.

Early in December 1955, King agreed to lead the first great African American nonviolent demonstration in the United States – the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The protest began after Rosa Parks, secretary of the local chapter of the NAACP, refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery bus and was arrested on December 1, 1955. In the highly segregated city, activists coordinated a bus boycott for 382 days. The protest placed a severe economic strain on the public transit system and downtown business owners. Montgomery found itself at the center of America’s civil rights struggle. Finally, in November 1956, the Supreme Court ruled that segregated seating on public buses was unconstitutional. Acting as the spokesperson for the boycott, King entered the national spotlight as an inspirational proponent of organized, nonviolent resistance. Unfortunately, he also became a target for white supremacists, who firebombed his home in January.

In 1957, Dr. King founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), another organization that promoted the civil rights movement. He then moved his family back to his hometown of Atlanta, Georgia, where he joined his father as co-pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church. However, he also continued to organize nonviolent protests against the unequal treatment of African American people.

In September 1958, while King was signing books in a Harlem, New York department store, he was stabbed in the chest by Izola Ware Curry. King survived to use the attempted assassination to reinforce his dedication to nonviolence:

“The experience of these last few days has deepened my faith in the relevance of the spirit of nonviolence if necessary, social change is peacefully to take place.”

As the spokesman of the SCLC, King traveled over six million miles and spoke over 1,500 times in the next decade. During this time, he planned drives to register Black voters, conferred with President John F. Kennedy, campaigned for President Lyndon B. Johnson, was arrested more than 20 times, was assaulted at least four times, and was awarded five honorary degrees.

Appearing wherever an injustice, protest, or action was needed, he led a massive protest in Birmingham, Alabama, one of America’s most racially divided cities, in 1963.

During this nonviolent protest, activists used boycotts, sit-ins, and marches to protest segregation and unfair hiring practices that caught the attention of the entire world. However, his tactics were tested when police brutality was used against the marchers, and King was arrested. But, his voice was not silenced, as he wrote his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” to refute his critics.

Later that year, King worked with several civil rights and religious groups to organize the March on Washington, D.C. for Jobs and Freedom, a peaceful political rally designed to shed light on the injustices African Americans continued to face across the country. Held on August 28, 1963, King was the principal speaker, where, in front of 250,000 people, he delivered his most famous speech – “l Have a Dream,” a spirited call for peace and equality. The speech and rally gained Martin Luther King, Jr. more publicity, and later that year, he was named “Man of the Year” by Time magazine. A few months later, he became the youngest person ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. At the time, he was 35 years old and turned over the prize money of $54,123 to the Civil Rights Movement.

In August 1964, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, which guaranteed all African Americans the right to vote — first awarded by the 15th Amendment –. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, was also passed. It also required equal access to public places and employment and enforced desegregation of schools and the right to vote. Though the acts did not end discrimination, they opened the door to progress further.

Still, Martin Luther King, Jr., who was by this time not only the symbolic leader of American blacks but also a world figure, had much to do. His philosophy remained peaceful, and he constantly reminded his followers that their fight would be victorious if they did not resort to violence. But still, he and his demonstrators were often threatened and attacked.

King continued his work by leading a voter registration campaign that ended in the Selma-to-Montgomery Freedom March. In the spring of 1965, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organized a voter registration campaign that drew international attention when violence erupted between white segregationists and peaceful demonstrators in Selma, Alabama. The violence, captured on television, was so brutal that it outraged Americans across the country who gathered in Alabama to take part in the Selma to Montgomery march led by King and supported by President Lyndon B. Johnson, who sent in federal troops to keep the peace. However, during the march, violence by state police and others against the peaceful marchers resulted in much publicity, which made Alabama’s racism visible nationwide.

The events in Selma deepened a growing rift between Martin Luther King, Jr. and young radicals who repudiated his nonviolent methods and commitment to working within the established political framework.

King next brought his crusade to Chicago, where he launched programs to rehabilitate the slums and provide housing.

As more militant black leaders rose to prominence, King broadened the scope of his activism to address issues such as the Vietnam War and poverty among Americans of all races. In 1967, King and the SCLC embarked on an ambitious program known as the Poor People’s Campaign, which included a massive march on the capital.

On the evening of April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was standing on the balcony of his motel room in Memphis, Tennessee, where he had traveled to lead a protest march in sympathy with striking garbage workers. Suddenly, he was hit by a rifle bullet in the neck and died at a hospital an hour later.

The Lorraine Motel, where King was assassinated, is now the site of the National Civil Rights Museum, photo courtesy Wikipedia.

In the wake of his death, a wave of riots swept major cities across the country, while President Johnson declared a national day of mourning.

King was killed by James Earl Ray, an escaped convict and known white supremacist. Ray pleaded guilty to the murder and was sentenced to 99 years in prison. However, he later recanted his confession but remained in jail until he died in 1998.

But King’s legacy lives on. The year after his death, his widow, Coretta Scott King, organized the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change. Standing next to his beloved Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, both sites are now part of the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park. The park also includes the 1895 two-story frame Queen Anne style house where King was born and lived for his first 12 years, the final resting place of Dr. & Mrs. King, a historic fire station, and the International Civil Rights Walk of Fame that gives recognition to courageous soldiers of justice who sacrificed and struggled to make quality a reality. Tributes are made to Rosa Parks, Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, Ambassador Andrew Young, US Congressman John Lewis, and more. The King Center is located at 449 Auburn Avenue, NE, Atlanta, Georgia, just east of downtown.

After years of campaigning by activists, Congress members, Coretta Scott King, and others, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill creating a U.S. federal holiday in honor of King in 1983. Observed on the third Monday of January, Martin Luther King Day was first celebrated in 1986.

The Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee, where he was shot, is now the National Civil Rights Museum. It is located at 450 Mulberry Street. The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., was dedicated in 2011.

King was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal.

Tomb of Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King at the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site in Atlanta, Georgia, courtesy Wikipedia.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Sources:

History.com

Isaacs, Sally Senzell; America in the Time of Martin Luther King Jr.: 1948 To 1976; Capstone Classroom, 1999.

King Center

Nobel Prize.org

Seattle Times

Wikipedia