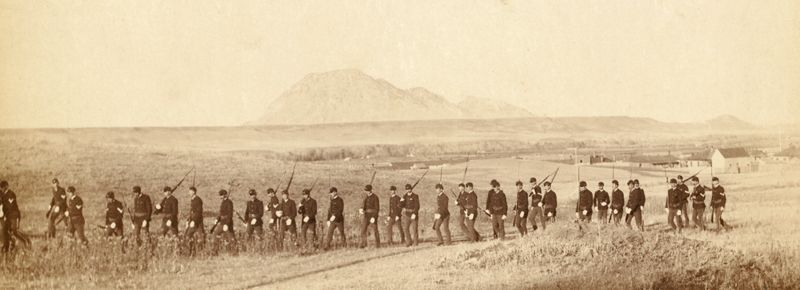

Company C, 3rd U.S. Infantry near Fort Meade, South Dakota, by John C.H. Grabill, 1890.

By Richard W. Stewart

Between the Civil War and the Spanish-American War, the mission of pacifying the frontier consumed the interest and attention of many Army officers and men.

One of the determining factors of life in the U.S. Army on the frontiers of America was the small size of the force engaged in operations in relative isolation from the country and the rest of the Army. The Army was scattered throughout hundreds of small forts, posts, outposts, and stations throughout the American West, often with little more than a company of cavalry or infantry in each post. On the one hand, this isolation bred a strong sense of camaraderie and bonding within the Army in a way that only shared suffering can do. The officers and men often felt part of an extended family that had to look inward for strength as it relied on its customs, rituals, and sense of honor separate from that distant civilian world or even from the very different military society “back East.” This sense of unity, of “splendid isolation,” kept the Army together as an institution during the harsh missions of western frontier duty but, at the same time, led far too often to professional and personal stagnation. The promotion was slow, and chances for glory were few, given the dangers and hardships of small-unit actions against an elusive foe.

The isolation also bred a certain reliance upon each other, as officers and soldiers developed various customs and rituals to bring structure to their lives. The formal rituals of a frontier post-life regulated by bugle calls, formal parades, Saturday night dances for the officers, distinctive uniforms, and unit nicknames — were attempts to deal with the tensions and pressures of a harsh life for a soldier and his family with low pay and little prestige. While perhaps glamorous in retrospect or when seen through the eye of Hollywood movies, such small communities also had their share of drunkenness, petty squabbles, corruption, arguments overrank and quarters, and other seemingly minor disputes so well known by many who have experienced life in small-town America. It was life at once dangerous and monotonous, comradely and isolated, professionally rewarding and stultifying. With low pay, poor quarters, an indifferent public, and a skilled foe that was at once feared, hated, and admired, the officers and men of the frontier Army seemed caught in a never-ending struggle with an elusive enemy and their environment. One historian summarized the Army post during this period on the frontier this way: “If one description could alone fit all frontier posts, it would be a monotonous routine relaxed only slightly by the color of the periodic ceremony.” This shared culture created many institutional myths and customs that continue to influence the Army’s image of itself today.

The manpower strains of all the various missions after the Civil War, plus manning all the frontier posts and stations, badly strained the resources of a shrinking Regular Army. As the post-Civil War Army took shape, its strength began a decade of decline, dropping from an 1867 level of 57,000 to half that in 1876, then leveling off at an average of 26,000 for the remaining years up to the Spanish-American War. Effective strength always lay below authorized strength, seriously impaired by high rates of sickness and desertion, for example. Because the Army’s military responsibilities were of continental proportions, involving sweeping distances, limited resources, and far-flung operations, an administrative structure was required for command and control. Therefore, the Army was organized on a territorial basis, with various geographical segments designated divisions, departments, and districts. There were frequent organization modifications, boundary rearrangements, and transfers of troops and posts to meet changing conditions.

The development of a basic defense system in the trans-Mississippi West followed the course of the empire. Territorial acquisition and exploration, succeeded by emigration and settlement, brought the settlers increasingly into collision with the Indians and progressively raised the need for military posts along the transcontinental trails and in settled areas.

The annexation of Texas in 1845, the settlement of the Oregon boundary dispute in 1846, and the successful conclusion of the Mexican-American War with the cession to the United States in 1848 of vast areas of land all had drawn the outlines of the primary task facing the Army in the West in the middle of the 19th century. Between the Mexican and Civil Wars, the Army had established a reasonably comprehensive system of forts to protect the arteries of travel and settlement areas across the frontier. At the same time, the Army had launched operations against Indian tribes that represented actual or potential threats to movement and settlement.

Militarily successful in some cases, these operations hardened Indian opposition, prompted wider provocations on both sides, and delineated an Indian barrier to westward expansion extending down the Great Plains from the Canadian to the Mexican border. For example, Brigadier General William S. Harney responded to the Sioux massacre of Lieutenant John L. Grattan’s detachment with a punishing attack on elements of that tribe on the Blue Water in Nebraska in 1855. Farther south, Colonel Edwin V. Sumner hit the Cheyenne on the Solomon Fork in Kansas in 1857. Brevet Major Earl Van Dorn fought the Comanche in two successful battles at Rush Spring in future Oklahoma and Crooked Creek in Kansas in 1858 and 1859, respectively. The Army on the Great Plains found itself in direct contact with a highly mobile and warlike culture that was not easily subdued.

In the Southwest, Army units pursued the Apache and Ute in New Mexico Territory between the wars, clashing with the Apache at Cieneguilla and Rio Caliente in 1854 and the Ute at Poncha Pass in 1855. Various expeditions against branches of the elusive Apache involved hard campaigning but few conclusive engagements, such as the one at Rio Gila in 1857. In 1861, Lieutenant George N. Bascom moved against Chief Cochise in this region, precipitating events that opened a quarter-century of hostilities with the Chiricahua Apache.

In the Northwest, where numerous small tribes existed, occasional hostilities existed between the late 1840s and the middle 1860s. Their general character was similar to operations elsewhere: settler intrusion, Indian reaction, and U.S. Army or local militia counteraction with superior force. The more important events involved the Rogue River Indians in Oregon between 1851 and 1856. The Yakama, Walla Walla, Cayuse, and other tribes on both sides of the Cascade Mountains in Washington in the latter half of the 1850s. The Army, often at odds with civil authority and public opinion in the area, found it necessary on occasion to protect Indians from settlers and the other way around.

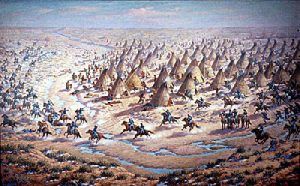

The Regular Army’s frontier mission was interrupted by the onset of the Civil War, and the task of dealing with the Indians was transferred to the volunteers. Although the Indians demonstrated an awareness of what was going on and took some satisfaction from the fact that their enemies were fighting each other, there is little evidence that they took advantage of the transition period between the removal of the regulars and the deployment of the volunteers. The so-called Great Sioux Uprising in Minnesota in 1862 that produced active campaigning in the Upper Missouri River region in 1863 and 1864 was spontaneous, and other clashes around the West were the result not of the withdrawal of the Regular Army from the West but the play of more fundamental and established forces. In many instances, the volunteer units were commanded by men of a very different stamp than Regular Army units. In one instance, a Colorado volunteer cavalry unit, commanded by a volunteer colonel named John M. Chivington, attacked and massacred several hundred peaceful Cheyenne Indians at Sand Creek, Colorado, in 1864 in one of the worst atrocities of the western wars. There were dangers in relying on volunteer units in this essential peacekeeping role. By 1865, overall Army strength in the frontier departments was about double what it had been in 1861. The volunteers kept pace with a continuing and gradually enlarging westward movement by further developing the forts their predecessors had begun.

The regional defense systems established in the West in the 1850s and 1860s provided a framework for deploying the Army as it returned from the Civil War to its frontier responsibilities. In the late summer of 1866, the general command and administrative structure for frontier defense comprised the Division of the Missouri, containing the Departments of Arkansas, Missouri, Dakota, and the Platte; the Division of the Pacific, consisting of the Departments of California and the Columbia; and the independent Department of the Gulf, whose area included Texas. However, by 1870, the Division of the Pacific included the Departments of Columbia, California, and Arizona. The Department of the Missouri covered the Departments of the Dakota, the Platte, and the Missouri; the Department of Texas was included in the Division of the South.

The Army’s challenge in the West was one of the environment and an adversary. In the summer of 1866, Ulysses S. Grant sent several senior officer inspectors across the country to observe and report on conditions. The theater of war was uninhabited or only sparsely settled. Its great distances and extreme variations of climate and geography accentuated manpower limitations, logistical and communications problems, and movement difficulties. The extension of the rail system only gradually eased the situation. Above all, the mounted tribes of the Plains were a different breed from the Indians the Army had dealt with previously in the forested areas of the East. Although the Army had fought Indians in the West in the period after the Mexican-American War, much of the direct experience of its officers and men had been lost during the Civil War years. Until frontier proficiency could be re-established, the Army would depend on the somewhat intangible body of knowledge that marks any institution fortified by the seasoning of the Civil War.

Of the officers who moved to the forefront of the Army in the Indian Wars, few had frontier and Indian experience. At the top levels at the outset, Grant had had only a taste of the loneliness of the frontier outpost as a captain. William T. Sherman had served in California during the 1850s but was not involved in the fighting. Philip H. Sheridan had served about five years in the Northwest as a junior officer, but neither Nelson A. nor Oliver O. Howard had known frontier service of any kind. Wesley Merritt, George A. Custer, and Ranald S. Mackenzie all had graduated from West Point into the Civil War. John Gibbon had only minor involvement in the Seminole War and some garrison duty in the West. Alfred Sully, also a veteran of the Seminole War and an active campaigner against the Sioux during Civil War years, fell into obscurity, while Philip St. George Cooke was overtaken by age, and Edward R. S. Canby’s experience was lost prematurely through his death at Indian hands. Christopher Augur, Alfred H., and George Crook were among the few upper-level Army leaders of the Indian Wars with pre-Civil War frontier experience.

Thus, to a large degree, the officers of the Indian Wars were products of the Civil War. Many brought outstanding records to the frontier, but this was a new conflict against an unorthodox enemy. Those who approached their new opponent respectfully and learned his ways became the best Indian fighters and, in some cases, the most helpful in promoting a solution to the Indian problem. Some who had little respect for the “savages” and placed too much store in Civil War methods and achievements paid the penalty on the battlefield. Captain William J. Fetterman would be one of the first to fall as the final chapter of the Indian Wars opened in 1866.

By Richard W. Stewart; American Military History, Volume I, Center of Military History, 2009. Compiled and edited Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

Also See: