By Henry Howe in 1857

The western coasts of North America were first partially explored by the Spaniards in the century succeeding the discovery of America. The English later followed their explorations. In 1578, Sir Francis Drake ranged this coast from 38 to 48 degrees. This region was called by the English New Albion. The name Oregon is from Oregano, the Spanish name for wild marjoram, and it is from this word, or some other similar, that its name is supposed to have arisen. But, little was known of even its coast up to the latter part of the last century [1700s]. Immediately after the last voyage of the renowned navigator, Captain Cook, the immense quantities of sea otter, beaver, and other valuable furs to be obtained on the northwest coast of America, and the enormous prices which they would bring in China, were communicated to civilized nations and created as much excitement as the discovery of a new gold region. A large number of people rushed at once into this lucrative traffic; so that in the year 1792, it is said that there were 21 vessels under different flags, but, principally American, plying along the coast of Oregon, and trading with the natives.

Up to this period, nothing was positively known of the Columbia River, the greatest stream which enters the Pacific from America. The Spanish navigator, Bruno de Heceta, in August 1776, first saw the opening through which its waters discharge into the ocean, and it was accordingly marked on the Spanish charts as the mouth of the river San Roque. In July 1788, Lieutenant John Meares of the British Navy, examined it and left with the conviction that no river was there; yet, this was the claim that the British set up to possession by the right of discovery. Vancouver, another British navigator, who was exploring the coast in 1792, confirmed this opinion. He stated that from Cape Mendocino, in California, to the Straits of Fuca, the southern boundary of Vancouver’s Island, there was not a single harbor, “the whole coast forming one compact and a nearly straight barrier against the sea.”

On May 7, 1792, Captain Robert Gray of the ship Columbia of Boston, Massachusetts, discovered and entered the river, which he named after his vessel. He was, in reality, the first person who established the fact of the existence of this great river, and this gave the United States the right to the country drained by its waters by the virtue of discovery.

In the autumn of 1792, Sir Alexander Mackenzie, with an exploring party, left Fort Chipewyan, on Athabasca Lake, midway between Hudson’s Bay and the Pacific Ocean, in the high northern latitude of 59 degrees, and reached the Pacific Ocean in July 1793, being thus the first white man who had ever crossed the American continent in its widest part. His route appears to have been some distance north of what is now the northern boundary of Oregon. In 1804-05, Lewis and Clark explored the country from the mouth of the Missouri River to that of the Columbia River. This exploration of the Columbia River, the first-ever made, constituted another ground for the claim of the United States to the country. In 1806, the British North West Fur Company established a trading post on Fraser’s Lake, which was the first settlement of any kind made by British subjects west of the Rocky Mountains. Other posts were established by them soon after in that region, which was then given the name of New Caledonia.

In 1808, the Missouri Fur Company, through their agent, Andrew Henry, established a trading post on the Lewis River, a branch of the Columbia. It was the first establishment of civilized people in what is now Oregon. An attempt was made that year by Captain Smith of the Albatross, of Boston to found a trading post on the south bank of the Columbia River, 40 miles from its mouth. It was abandoned in the same season and that of Andrew Henry’s in 1810.

In 1810, John Jacob Astor, a German merchant of New York, who had accumulated an immense fortune by commerce in the Pacific and China, formed the Pacific Fur Company. His first objectives were to concentrate on the company, the fur trade in the unsettled parts of America, and the supply of merchandise for the Russian fur trading establishments in the North Pacific. For these purposes, posts were to be established on the Missouri River, the Columbia River, and the vicinity. These posts were to be supplied with the merchandise required for trading by ships from the Atlantic coast or across the country by way of the Missouri River. A factory or depot was to be founded on the Pacific for receiving this merchandise, and distributing it to the different posts and for receiving, in turn, furs from them, which were to be sent by ships from thence to Canton. Vessels were also to be sent from the United States to the factory with merchandise, to be traded for furs, which would then be sent to Canton, and there exchanged for teas, silks, etc., to be in turn distributed in Europe and America.

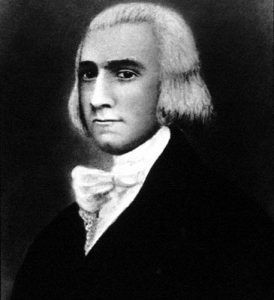

This stupendous enterprise at the time appeared practicable. The only party from whom any rivalry could be expected was the British North West Fur Company, whose means were far inferior to those of Astor. From motives of policy, he offered them one-third interest, which they declined, secretly intending to forestall him. Having matured his scheme, John Jacob Astor engaged partners, clerks, and voyageurs, most of whom were Scotchmen and Canadians, previously in the North West Fur Company service. Wilson P. Hunt of New Jersey was chosen as the chief agent of operations in Western America.

In September 1810, the ship Tonquin, Captain Samuel Thorn, left New York for the mouth of the Columbia River with four of the partners, Alexander McKay, Duncan McDougall, and David and Robert Stuart, all British subjects, with clerks, voyageurs, and mechanics. In January 1811, the second detachment, with Wilson Hunt, Robert McClellan, Kenneth McKenzie, and Ramsey Crooks, also left New York to go overland by the Missouri River to the same point, and in October 1811, the ship Beaver, Captain Cornelius Sowles, with several clerks and attaches left New York for the North Pacific. Before these, in 1809, John Jacob Astor had dispatched the Enterprise, Captain John Ebberts, to make observations at the Russian settlements and to prepare the way for settlements in Oregon. He also, in 1811, sent an agent to St. Petersburg, who obtained from the Russian American Fur Company the monopoly of supplying their posts in the North Pacific with merchandise and receiving furs in exchange.

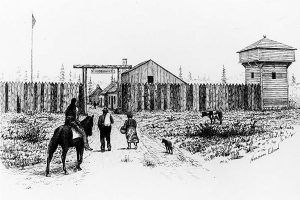

In March 1811, the Tonquin arrived at the Columbia River. Soon after, they commenced erecting on the south bank, a few miles inland, their factory or depot building, named Astoria. In June, the Tonquin, with Alexander McKay, sailed north to arrange to trade with the Russians. In July, the Astorians were surprised by the appearance of a party of the North West fur company, under Mr. Thompson, who had come overland from Canada to forestall them in the occupation of the mouth of the Columbia; but had been delayed too late for this purpose, in seeking a passage through the Rocky Mountains, and had been obliged to winter there. Mr. Thompson was accompanied on his return by David Stuart, who founded the trading post called Okonogan.

At the beginning of 1812, the detachment of Wilson Hunt came into Astoria in parties and a wretched condition. They had been over a year in coming from St. Louis, Missouri; they had undergone extreme suffering from hunger, thirst, and cold in their wanderings that winter, through the dreary wilderness of snow-clad mountains, from which, and other causes, numbers of them perished. In May 1812, the Beaver brought the third detachment under Mr. Clarke, arrived at Astoria. They brought a letter that had been left at the Sandwich Islands by Captain Ebbets of the Enterprise, containing the sad intelligence that the Tonquin and her crew had been destroyed by Indians near the Straits of Fuca the June preceding.

In August 1812, Wilson Hunt, leaving Astoria in the charge of Duncan McDougall, embarked in the Beaver to trade with the Russian posts, which was to have been done by the Tonquin. He was successful and effected a highly advantageous arrangement at Sitka with Baranof, Governor of Russian America; took in a rich cargo of furs, and dispatched the vessel to Canton via the Sandwich Islands, where he, in person, remained, and in 1814, he returned to Astoria in the Peddler, which he had chartered, and found that Astoria was in the hands of the North West Fur Company.

When Hunt left in the Beaver, a party was dispatched, establishing a trading post on the Spokane. Ramsey Crooks, Robert McClellan, and Robert Stuart set out and crossed overland to New York with an account of what had been done. The trade was, in the meantime, very prosperous, and a large quantity of furs had been collected at Astoria.

In January 1813, the Astorians learned from a trading vessel that a war had broken out with England. A short time after, John Mactavish and Joseph Laroque, partners of the North West Company, arrived at Astoria; Duncan McDougall and Kenneth McKenzie (both Scotchmen) were the only partners there, and they unwisely agreed to dissolve the company in July. Stuart and Clarke, at the Okonogan and Spokane posts, opposed this; but it was finally agreed that if assistance did not soon arrive from the United States, they would abandon the enterprise.

Mactavish and his followers of the North West Company again visited Astoria, where they expected to meet the Isaac Todd, an armed ship from London, which had orders “to take and destroy everything American on the northwest coast.” Notwithstanding, they were hospitably received and held private conferences with Duncan McDougall and Kenneth McKenzie, the result of which was that they sold out the establishment, furs, and supplies of the Pacific Fur Company in the country, to the North West Company, for about $58,000. That company was thus enabled to establish itself in the country.

Thus ended the Astoria enterprise. Had the directing partners on the Columbia River been Americans instead of foreigners, it is believed that they would have withstood all their difficulties, notwithstanding the war. The sale was considered disgraceful, and the conduct of Duncan McDougall and Kenneth McKenzie in that sale and subsequently were such as to authorize suspicions against their motives; yet, they could not have been expected to engage in hostilities against their countrymen and old friends.

The British changed the name of Astoria to that of Fort George. From 1813 to 1823, few, if any, American citizens entered the countries west of the Rocky Mountains. Nearly all the trade of the Upper Mississippi and Missouri Rivers was carried on by the American Fur Company, of which Astor was the head, and by the Columbia Fur Company, formed in 1822, composed mainly of persons who had been in the service of the North West Company, and were dissatisfied with it. The Columbia Fur Company established posts on the upper waters of the Mississippi River, the Missouri River, and the Yellowstone, which were transferred, in 1826, to the North American Company on the junction of the two bodies. About this time, the overland trade with Santa Fe commenced, with caravans passing regularly every summer between St. Louis and that place. In 1824, Ashley of St. Louis re-established commercial communications with the countries west of the Rocky Mountains and built a trading post on Ashley’s Lake in Utah.

These active proceedings of the Missouri Fur Company traders stimulated the American Fur Company to send their agents and attaches beyond the Rocky Mountains, although they built no posts. In 1827, Johsua Pilcher of Missouri went through the South Pass with 45 men and wintered on the headwaters of the Colorado River in what is now the northeast part of Utah. The following year he proceeded northwardly along the base of the Rocky Mountains to near latitude 47 degrees. There, he remained until the spring of 1829, when he descended Clark River to Fort Colville, then recently established at the Falls by the Hudson’s Bay Company, which had, a few years previous, absorbed and united the interests of the North West Company. He returned to the United States through the long and circuitous far northward route of the Upper Columbia, the Athabasca, the Assiniboin, the Red River, and the Upper Missouri River. But, little was known of the countries through which Pilcher traversed previous to the publication of his concise narrative. The account of the rambles of J.O. Pattie, a Missouri Fur Company trader through New Mexico, Chihuahua, Sonora, and California, threw some light on the geography of those countries. In 1832, Captain Bonneville of the U.S. Army, while on furlough, led a party of 100 men from Missouri over the mountains. He passed more than two years on the Columbia and the Colorado Rivers in hunting, trapping, and trading.

At about the same time, Captain Nathaniel Wyeth of Massachusetts attempted to establish commercial relations with the countries on the Columbia River, to which the name of Oregon began to be universally applied. His plan was like that of John Jacob Astor’s, with the additional scheme of transporting the salmon of the Oregon rivers to the United States. He made two overland expeditions to Oregon, established Fort Hall as a trading post in present-day Idaho, and another, mainly for fishing purposes, near the mouth of the Willamette River. This scheme failed, owing to the rivalry of the Hudson’s Bay Company, who founded the counter-establishment of Fort Boise, where offering goods to the Indians at lower prices than Wyeth could afford compelled him to desist, and he sold out his interests to them. Meanwhile, a brig he had dispatched from Boston arrived in the Columbia and returned with a cargo of salted salmon, but the results not being auspicious, the enterprise was abandoned.

The American traders being excluded by these, and other means from Oregon, mainly confined themselves to the regions of the head-waters of the Colorado River and the Utah Lake, where they formed one or two small establishments and sometimes extended their rambles as far west as San Francisco and Monterey, California. The number of American hunters and trappers thus employed west of the Rocky Mountains seldom exceeded 200, where, during the greater part of the year, they roved through the wilds in search of furs which they conveyed to their places of rendezvous in the mountain valleys, and bartered with them to the Missouri traders.

About the time of Nathaniel Wyeth’s expeditions were the earliest emigrations to Oregon of settlers from the United States. The first of these was founded in 1834, in the Willamette Valley, by a body of Methodists who went round by sea under the direction of the Reverends Jason Lee and Cyrus Shepherd. In that valley, a few retired servants of the Hudson’s Bay Company were then residing and engaged in herding cattle. The Congregationalists or Presbyterians planted colonies two or three years after, in the Walla Walla and Spokane countries, with the Reverends Samuel Parker, Henry Spalding, William Gray, Elkanah Walker, Cushing Eels, John Smith Griffin, and Dr. Marcus Whitman as missionaries.

In all of these places, mission schools were established for the instruction of the natives, and in 1839, a printing press was started at Walla Walla, Washington, where were printed the first sheets ever struck off on the Pacific side of the mountains north of Mexico. On it, books were printed from types set by native compositors. The Roman Catholics from Missouri soon after founded stations on the Clark River.

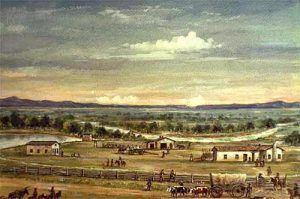

In about 1837, the American people began to be deeply interested in the subject of the claims of the United States to Oregon, and societies were formed for emigration. Petitions from them and other sources were presented to Congress to either make a definite arrangement with Great Britain, the other claimant or take immediate possession of the country. Each year, from 1838 to 1843, small parties emigrated overland from Missouri to Oregon, suffering much hardship on the route. At the close of 1842, the American citizens there numbered about four hundred. Relying upon the promise of protection held out by the passage of the bill in February 1843 by the U. S. Senate for the immediate occupation of Oregon, about 1,000 emigrants, men, women, and children, assembled at Westport, on the Missouri frontier in the succeeding June, and followed the route up the Platte River, and through the South Pass, surveyed the previous year by Charles Fremont; thence by Fort Hall, Idaho to the Willamette Valley, where they arrived in October, after a laborious and fatiguing journey of more than 2,000 miles. Others soon followed, and before the close of the next year, over 3,000 American citizens were in Oregon.

By the treaty for the purchase of Florida in 1819, the boundary between the Spanish possessions and the United States was fixed on the north-west at 42 degrees latitude, the present northern line of Utah and California; by this, the United States succeeded to the title to Oregon as Spain may have derived, by the right of discovery through its early navigators. In June 1846, all the difficulties concerning Oregon, which at one time threatened war, were settled by a treaty between the two nations. In general terms, the treaty established the northern boundary; British subjects were allowed the free navigation of the Columbia River, and the Hudson’s Bay Company and all British subjects were to be continued in possession of whatever land or property they at that time held in Oregon.

The principal obstacle to a previous settlement had been the company’s influence. The English people at large knew little of and took but slight interest in the country. The British first, through the North West Company and then through the son’s Bay Company (into which the former became absorbed), from 1814 to 1840, had enjoyed the almost exclusive use of Oregon. The son’s Bay Company received from the British government, to the exclusion of all other British subjects, the exclusive right to trade west of the Rocky Mountains, where the fur-bearing animals were more abundant than in any other part of the world.

The Company’s constitution is to secure knowledge and prudence in council and readiness and exactness in execution. Their treatment of the Indians admirably combined policy and humanity. Ardent spirits were prohibited from being sold to them; schools for the instruction of the Indian children were established at each of the trading posts, and hospitals for the sick; missionaries of various sects were encouraged and fostered, and all emigrants from the United States and elsewhere were treated with the utmost kindness and hospitality. But, no sooner did any of them attempt to hunt, trap, or trade with the natives, than the competition of the body was turned against him, and he was compelled to desist. As the fur trade began to decline, the company turned its attention to agriculture, lumbering, fishing, and other pursuits.

In 1841, the coast of Oregon was visited by the ships of the United Exploring Expeditions under Lieutenant Charles Wilkes. He arrived in the sloop of war Vincennes, off the mouth of the Columbia River, on April 27, but, finding it hazardous to attempt the entrance, he sailed to the Straits of Fuca, the southern boundary of Vancouver’s Island, and anchored in Puget’s Sound, near Fort Nasqually, Washington from which he dispatched several surveying parties into the interior. One of these crossed the great westernmost range of mountains to the Columbia River and having visited the British trading posts of Okonogan, Colville, and Walla Walla, returned to Nasqually. Another party proceeded southward to the Cowelitz, a stream running south and emptying into Columbia River about forty miles from the ocean. From the mouth of the Cowelitz, they went up the Columbia to Walla Walla, and down again to the ocean. In the meantime, other parties were engaged in surveying the coasts and harbors on the Pacific, the Straits of Fuca, and Admiralty Inlet, particularly in exploring the valleys of the Willamette, emptying into the Columbia, and of the Sacramento River of California. During these duties, the sloop of war Peacock was lost on the bar at the mouth of the Columbia River; but the crew, instruments, and papers were saved.

At that time, Wilkes estimated the population to be: of Indians, 19,199; Canadians and half-breeds, 650; and the citizens of the United States, 150. The Hudson’s Bay Company had 25 forts and trading stations in Oregon. Dr. John McLoughlin, the company’s executive officer, was kind to the American settlers and, although a Catholic, was noted for his hospitality to the Methodist and Presbyterian missionaries. The Hudson’s Bay Company charter prevented them from engaging in agriculture; its officers, agents, and servants organized another company for this purpose, with a capital of two million, called the Puget Sound Company. They began by making large importations of stock from California and some of the choicest breeds from England. They entered into farming on an extensive scale. Almost all their trading establishments were later changed into agricultural ones, and they almost entirely supplied all their stations and forts and the Russian ports in the north with wheat, butter, and cheese.

Among the most marked incidents in the history of Oregon was the Cayuse War in the winter of 1847-48. It grew out of these circumstances: The Reverend Dr. Marcus Whitman, a Presbyterian missionary, who, besides his religious duties, had established a fort and trading post in the Walla Walla Valley and employed large numbers of Indians and emigrants in agriculture. Many of these Cayuse Indians had, under his guidance, become partially civilized and were good farmers. He was eminent for his hospitality to the newly-arrived and exhausted emigrants and was popular with all. His lady was also remarkable for her kindness and, at that time, was administering to the Indians the measles, which extensively prevailed among them. Many died of the disease; they became suspicious that they were poisoned by the medicines given to them by the Whitmans. On November 29, 1947, at about noon, the Indians rushed into the fort, murdered Dr. Marcus Whitman and his wife, and 13 others, took 61 people prisoners, and burnt the fort and houses of the settlement. Upon receiving the news in the Willamette settlements, troops were raised, the Indians were defeated in three battles, and their villages and provisions were destroyed. The prisoners were eventually released, through the praiseworthy efforts of Peter Sken Ogden, chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Oregon was organized as a territory in 1848. It has an average width east and west of about 680 miles and north and south of 500 miles, giving an area of about 340,000 square miles. It is divided into three natural sections:

The first section is between the Pacific Ocean and the President’s Range or the Cascade Mountains. The Cascade Range runs parallel with the sea coast, the whole length of the territory, and is continued through California under the name of the Sierra Nevada. It rises in many places in conical peaks to the height of 12,000 and 14,000 feet, or over two miles above the ocean level. The distance from the seashore to this chain is from 100-150 miles; there were a few mountain passes, but they were difficult and could only be attempted late in the spring and summer. The climate of this section is mild throughout the year, neither experiencing the extreme cold of winter nor the heat of summer. The prevailing winds in the summer are from the northward and westward, and in winter, the southward, westward, and southeast are tempestuous. The winter is supposed to last from December to February. Rains usually begin to fall in November and last until March, but they are not heavy, though frequent. Snow sometimes falls, but it seldom lies over three days. The frosts are early, occurring in the latter part of August; this, however, is to be accounted for by the proximity of the mountains. Fruit trees blossom early in April. The soil, in the northern parts, varies from a light brown loam to a thin vegetable earth, with gravel and sand as a subsoil; in the middle parts, from a rich heavy loam and unctuous clay to a deep heavy black loam, on a caprock; and in the southern (the Willamette Valley) the soil is generally good, varying from a black vegetable loam to decomposed basalt, with stiff clay, and portions of loose gravel soil. The hills are generally basalt, stone, and slate; between the Umpqua River and the southern boundary, the rocks are primitive, consisting of slate, hornblende, and granite, which produce a gritty and poor soil; there are, however, some places of rich prairie, covered with oaks. It is, for the most part, a well-timbered country. It is intersected with the spurs or offsets from the Cascade Mountains, which render its surface much broken; these are covered with a dense forest. The timber consists of pines, firs, spruce, oaks (red and white), ash, arbutus, arbor vitae, cedar, poplar, maple, willow, cherry, and tew, with a close undergrowth of hazel, rubus, and roses. The richest and best soil is found on the second or middle prairie and is best adapted for agriculture, the high and low being excellent for pasture land. The climate and soil are admirably adapted for all kinds of grain—wheat, rye, oats, barley, peas, etc. Indian corn does not thrive in any part of this territory or the Mississippi Valley. Many fruits appear to succeed well, particularly the apple and pear. Vegetables grow exceedingly well and yield most abundantly.

The Second or Middle Section is between the Cascade and Blue Mountain Ranges. The Blue Mountains are irregular in their course and occasionally interrupted but generally run in a northerly direction; they commence in the Klamet range, near the southern boundary of the territory; the Saptin or Snake River breaks through them at the junction of the Kooskooskee River, and branch of it in hills of moderate elevation, until they again appear on the north side of the Columbia River, above the Okonogan River, passing in a northern direction, until they unite with the Rocky Mountains. The climate of the middle section is variable; during the summer, the atmosphere is much drier and warmer, and the winter much colder than in the western section. Its extremes of heat and cold are more frequent and greater, the mercury, at times, falling as low as minus 18 degrees in winter and rising to 108 degrees in the shade of summer; the daily difference in temperature is about 40 degrees. It has, however, been found extremely salubrious, possessing a pure and healthy air. No dews fall in this section. The soil is, for the most part, a light sandy loam; in the valleys, a rich alluvial, and the hills are generally barren. The surface is about 1,000 feet above the level of the western section and is generally a rolling prairie country. In the center of this section, and near and around the junction of the Saptin or Snake and Columbia Rivers, is an extensive rolling country well adapted for grazing. South of the Columbia River and extending to the southern boundary of the territory, it is destitute of timber or wood unless the wormwood (artemisia) may be so-called. However, there are portions of it that might be advantageously farmed.

The Third, or East Section, is between the Rocky and the Blue Mountains. The Rocky Mountains commence on the Arctic coast and continue an almost” unbroken chain until they merge in the Andes of South America. That part forming the eastern boundary of Oregon, extending north from the Great South Pass at the Committee’s Punch-bowl Pass, forms an almost impenetrable barrier, the few passes between were very difficult and dangerous. The climate of the eastern section is extremely variable. On each day, there are all the changes incident to spring, summer, autumn, and winter. There are places where small farms might be located, but they are few. The soil is rocky and broken and presents an almost unbroken barren waste. Stupendous mountain spurs traverse it in all directions, affording little level ground. Snow lies on the mountains, nearly, if not quite, throughout the year. It is exceedingly dry and arid; rains seldom fall, and but little snow. This country is partially timbered, and the soil is much impregnated with salts.