Fort Laramie History

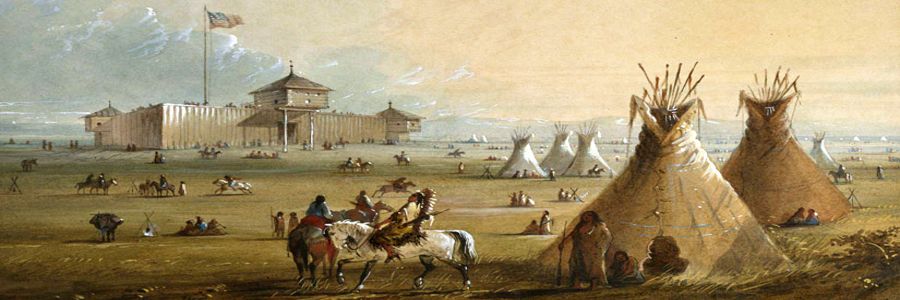

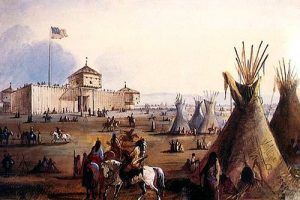

Fort Laramie, Wyoming, was located at the Crossroads of a nation moving west. In 1834, a fur-trading post was established where the Cheyenne and Arapaho traveled, traded, and hunted. Although it was not originally a military fort, it was named Fort William and soon became a place of safety as settlers moved across the continent.

By the 1840s, wagon trains would rest and resupply here, en route to Oregon, California, and Utah. In 1841, Fort John was constructed to replace the original wooden stockade at Fort William. Built of adobe brick, Fort John stood on a bluff overlooking the Laramie River. It was named after John Sarpy, a partner of the American Fur Company, but it was more commonly known as Fort Laramie among employees and travelers.

Fort Laramie, the military post, was founded in 1849, when the Army purchased the old Fort John for $4000 and began construction of a military outpost along the Oregon Trail. For many years, the Plains Indians and the travelers along the Oregon Trail had coexisted peacefully. As the number of emigrants increased, tensions between the two cultures intensified.

To help ensure the safety of the travelers, Congress approved the establishment of forts along the Oregon Trail and a special regiment of Mounted Riflemen to man them. Fort Laramie was the second of these forts to be established.

The popular view of a western fort, perhaps shaped by Hollywood films, is of an enclosure surrounded by a wall or stockade. Fort Laramie, however, was never enclosed by a wall. Initial plans for the fort included either a wooden fence or a thick rubble wall, nine feet high, that enclosed an area 550 feet by 650 feet. Because of the high costs involved, however, the wall was never built. Fort Laramie was always an open fort that depended on its location and garrisoned troops for security.

In the 1850s, one of the main functions of the troops stationed at the fort was patrolling and maintaining the security of a lengthy stretch of the Oregon Trail. This was a difficult task due to the garrison’s small size and the vast distances involved. In 1851, a treaty was signed between the United States and the most important Plains Indian tribes. The peace that it inaugurated, however, lasted only three years. In 1854, an incident involving a passing wagon train precipitated the Grattan Fight, in which an officer, an interpreter, and 29 soldiers from Fort Laramie were killed. This incident was one of several that ignited a conflict between the United States and the Plains Indians that would not be resolved until the late 1870s.

The 1860s brought a different type of soldier to Fort Laramie. After the beginning of the Civil War, most regular army troops were withdrawn to the East to participate in that conflict. State volunteer regiments garrisoned the fort, such as the Seventh Iowa and the Eleventh Ohio.

The stream of emigrants along the Oregon Trail began to diminish, but the completion of the transcontinental telegraph line in 1861 brought new responsibilities to the soldiers. Inspection, defense, and repair of the “talking wire” were added to their duties. During the latter part of the 1860s, troops from Fort Laramie supplied and reinforced the forts along the Bozeman Trail until the Signing of the Treaty of 1868.

Unfortunately, the Treaty of 1868 did not end the conflict between the United States and the Plains Indians, and by the 1870s, significant campaigns were being mounted against the Plains tribes.

The discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1874 and the resultant rush to the goldfields violated some of the treaty’s terms and antagonized the Sioux, who regarded the Hills as sacred ground. Under leaders such as Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, they and their allies chose to fight to keep their land. In campaigns such as those in 1876, Fort Laramie served as a staging area for troops, a communications and logistical center, and a command post.

Conflicts with the Indians on the Northern Plains had abated by the 1880s. Relieved of some of its military functions, Fort Laramie entered a Victorian-era period of relative comfort. Boardwalks were built in front of officers’ houses, and trees were planted to soften the stark landscape.

By the end of the 1880s, the Army recognized that Fort Laramie had served its purpose. Many vital events on the Northern Plains involved the Fort, and many arteries of transport and communication passed through it. Perhaps the most important artery, however, was the Union Pacific Railroad, which had bypassed it to the South. In March 1890, troops marched out of Fort Laramie for the last time. The land and buildings that comprised the Fort were auctioned to civilians.

Fort Laramie National Historic Site

The post hospital at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, was built in 1873 on the site of the old cemetery. It had 12 beds and contained a dispensary, kitchen, dining room, isolation rooms, and a surgeon’s office. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

This unique historic place preserves and interprets one of America’s most essential locations in the history of westward expansion and Indian resistance. When Fort Laramie closed in 1890, its legacy was one of peace and war, cooperation and conflict; it was a place where the West we know today was forged.

Fort Laramie was proclaimed a National Monument in 1938 and named a National Historic Site in 1960.

Today, the site preserves a 19th-century United States military post, including 11 restored buildings: “Old Bedlam,” the post headquarters and officers’ quarters built in 1849; the cavalry barracks built in 1874; Sutler’s Store; a stone guardhouse; and a bakery. A museum exhibits artifacts of the Northern Plains.

The National Park Service administers the historic site, which encompasses 833 acres.

Contact Information:

Fort Laramie National Park Service

965 Gray Rocks Road

Fort Laramie, Wyoming 82212

307-837-2221

In 1851, United States government officials met with Great Plains tribal leaders in Fort Laramie, Wyoming. They negotiated the Fort Laramie Treaty, which was meant to resolve conflict among hostile Native American groups and between Native Americans and whites. This treaty established territorial claims for the Blackfeet in north-central Montana, the Crow in the Yellowstone Valley, and the Assiniboine in northeastern Montana.

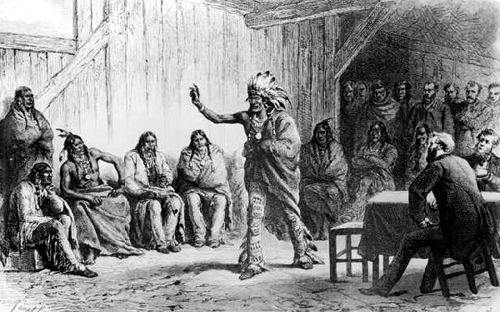

Spotted Tail, Roman Nose, Old Man Afraid of His Horses, Lone Horn, Whistling Elk, Pipe, and Slow Bull met at Fort Laramie with peace commissioners to negotiate, perhaps, the most important treaty of the 19th century – closing the Bozeman Trail and creating the great Sioux Reservation.

Four years later, Washington territorial governor Isaac Stevens opened negotiations with the Flathead, Kootenai, Pend d’Oreille (primarily in Idaho), and later with the Blackfeet. Stevens intended to remove Native Americans to reservations.

In exchange for ceded lands, Stevens promised the Native American groups improvements to reservations and annuities. The Flathead, Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai agreed to share the Jocko Indian Reservation, which covered about 518,000 hectares (about 1,280,000 acres) to the south of Flathead Lake. The Flathead, reluctant to leave the Bitterroot Valley, inserted a clause into the treaty that allowed them to stay in their home temporarily. The Blackfeet also signed a treaty that bound them to a region in northern Montana. By 1868, nearly one-quarter of Montana had been set aside for reservations. However, whites frequently violated the treaties by using Native American land.

As Montana became more populous during the 1860s gold rushes, white settlers and Native Americans clashed. Although the incidents were generally minor — a stolen horse or missing livestock– occasionally, settlers or Native Americans were killed. In response to these incidents, the white immigrants demanded federal protection. In 1866, the army established Fort C.F. Smith, its first post in Montana. Later forts were built along the Mullan Road, near the Bozeman Trail, and to the east of Helena.

In 1869, a series of attacks on white settlers and Native Americans drove the settlers from around Fort Benton to demand military action. Major Eugene M. Baker, who believed that the Blackfeet were responsible for the violence, led an attack on an innocent Blackfeet camp. This offensive left 173 Blackfeet dead. The Blackfeet, divided about how to react to the massacre, did not mount a counterattack.

Fort Laramie Grand Council.

The gold rush also provoked conflict between the Sioux and the white settlers in Montana. The Sioux opposed the use of the Bozeman Trail, which crossed Sioux territory on the Great Plains, to reach mining districts. The federal government attempted to negotiate with the Sioux at Fort Laramie in 1866, but the Sioux broke off the talks. The Sioux regularly attacked settlements and travelers along the Bozeman Trail for the next few years. In 1868, the government and the Sioux met again at Fort Laramie. They signed a treaty that closed the Bozeman Trail and provided a reservation for the Sioux in the Black Hills in Dakota Territory.

Some Sioux were dissatisfied with this agreement, including Sioux leaders Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. This group continued to live near the Bozeman Trail. In 1874, gold was discovered within the reservation boundaries in the Black Hills, attracting white prospectors. Some Sioux left the reservation to join Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. In 1876, the United States government sent troops, including Lieutenant Colonel George Custer and his regiment, to relocate this group to the reservation. On June 25, 1876, a Sioux force under Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse defeated Custer’s troops at the Little Bighorn. Although the Sioux were victorious in this famous battle, the United States sent reinforcements, and Crazy Horse gave up his arms in 1877. Sitting Bull conceded victory to the United States in 1881.

Go to: Fort Laramie Treaty Document

See our Fort Laramie Photo Gallery HERE.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2025.

Also See:

Forts & Presidios Across America

Sources:

“Fort Laramie Treaty” Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia 2003

Fort Laramie National Park Service