Independence, Missouri, is known as the “Queen City of the Trails” because it was a point of departure for the California, Oregon, and the Santa Fe Trail.

Lying on the south bank of the Missouri River, near the northwestern edge of Missouri, Independence was originally called home to the Kanza and Osage Indians, who called the area Big Spring. Few towns its size can claim such a rich history. The first explorers to the area were the Spanish, followed by the French. The region became American territory with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

In 1804, Lewis and Clark recorded in their journals that they stopped here to pick plums, raspberries, and wild apples. On August 10, 1821, Missouri became a state, and through the Treaties of 1825 with the Osage and Kanza Indians, the U.S. government took control of the area. Jackson County was organized on December 15, 1826, and the land was opened up for settlement. Searching for a site for the county seat, the Missouri General Assembly chose Big Spring, and on March 29, 1827, authorities approved a 160-acre site which became Independence.

In the meantime, William Becknell had blazed the Santa Fe Trail in 1821 from Franklin, Missouri, some 100 miles to the east, passing right through the area that would later become Independence. As the town grew, it soon became the eastern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail. In 1831, a boat landing was established at Blue Mills on the Missouri River, six miles distant. The business increased, and the government established a customs house accommodating the early merchants.

William Becknell blazes the Santa Fe Trail.

In 1830, Mormon missionaries began moving into the area in hopes of converting the Indians living in western Missouri and eastern Kansas. Church elders from Ohio chose the growing frontier town as their base. The following summer, in August 1831, founder and prophet Joseph Smith, Jr. visited Independence and declared it the location of Zion, God’s city on earth. When the news spread that Zion had been found, the Mormons of Ohio, Illinois, and New York began an exodus to Jackson County. Smith purchased 40 acres of land for the temple just west of the courthouse in Independence. The country around Independence soon was settled with Mormons, who built numerous homes, churches, and mills, established businesses, and began one of the first newspapers — the Evening and Morning Star, established by W. W. Phelps.

However, non-church community members were not pleased with their presence, and trouble followed. They made many charges against the Mormons, the principal one of which was that they were abolitionists. Vandalism against church members first occurred in the spring of 1832, but coordinated aggression began in July 1833, when the Evening and Morning Star published an article entitled “Free People of Color.”

Though the article was written to curtail trouble, it had the opposite effect, so outraging local citizens that more than 400 met at the courthouse to demand that the Mormons leave. When the church members refused to negotiate away or abandon lands they legally owned, several citizens formed a mob, destroyed the press and printing house, ransacked the Mormon store, and violently accosted Mormon leaders. Bishop Edward Partridge was beaten and tarred, and feathered. Meeting three days later, the mob issued an ultimatum: One-half of the Mormons must leave by year’s end and the rest by April 1834.

The church members decided to stand their ground and seek redress through the courts. The Gentile settlers, however, were having none of it. In October, they mobilized again to drive the Mormons out. On October 31, 1833, they attacked the Whitmer settlement a few miles west of the Big Blue River, demolishing houses, whipping the men, and terrorizing the women and children. The attacks and depredations against church members continued throughout the next week resulting in the deaths of two Missourians and one defender. The county militia was finally called out to quell the mob and negotiate a truce. When the church members surrendered their arms to the militia, the troops joined the mob in a general assault against them. The terrified church members, numbering about 1,200, fled Jackson County in disarray. Most went north, across the Missouri River, and sought refuge in Clay County.

Their property was either confiscated or destroyed. They drifted about over the state, living in one town and then another until 1838, when the troubles between the Mormons and the Gentiles resulted in a miniature civil war. On October 27, 1838, Missouri Governor Boggs ordered that the Mormons “must be exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for the public good.” Major General Clark enforced the order. Many of the Mormon leaders were taken prisoners, but most of them subsequently escaped. The rest of the Mormons of Missouri, who had grown to more than 12,000, emigrated in the winter of 1838-39 to Illinois, where they formed the town of Nauvoo. The lot the church had purchased to build a temple was sold for taxes.

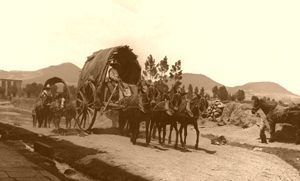

Mexican Wagons

By 1835 the growing frontier village had a second road surveyed and built southwest of town towards Santa Fe, and the town’s trading strength was reinforced by Mexican merchants who came northeast along the trail. Independence was the farthest point westward on the Missouri River, where steamboats or other cargo vessels could travel, and trade flourished in the city, accommodating fur traders, merchants, and adventurers. Large freighting wagons rolled past the courthouse square to and from Santa Fe for the next two decades.

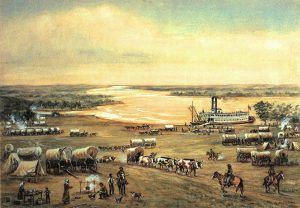

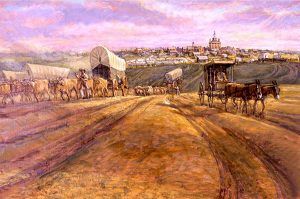

In the early 1840s, tens of thousands of emigrants began to come to Independence from the east to get outfitted and depart west on the five-month, 2,000-mile trek along the Oregon and California Trails. The city soon became known as the Queen City of the Trails as goods and services were provided for travelers beginning their long journeys.

Samuel C. Owens was the first trader in Independence. He came to Missouri from Kentucky when he was a young man. He was the first clerk of the circuit court of Jackson County. John Aull, his business partner, had owned a store in Lexington, Missouri. Owens and James Aull lost their lives while on Doniphan’s Expedition into Mexico. John C. McCoy gave this account of their unfortunate adventure:

Trails Leaving Independence by Charles Goslin mural hangs in the National Trails Museum in Independence, Missouri.

“Colonel Owens’ acquaintance with the traders did much to retain Independence as the ‘entropo’ into Mexico, and until the troubles between the United States and Mexico began in 1845-46, other places were not used. In the year 1846, it was determined by the United States to send troops across the plains to overcome opposition. Doniphan raised a regiment of men who, being fully equipped, took up the march from this country. Quite a number of adventurers of all sorts accompanied the troops. Owens and Aull decided to send a wagon load of goods along, and Mr. Owens and James Aull took charge of it. Everything promised well, and no opposition was met with until within sight of the Sacramento plains, between Santa Fe and Chihuahua, where the Mexicans were drawn up for battle.

The civilians, teamsters, and others accompanying our troops were organized into a company with Colonel S. C. Owens as captain to aid Doniphan’s men. On the field, the order was given to charge, and Colonel Owens rashly dashed forward in front of his men and was killed, thus early in the strife. Great was the regret of his men to see one esteemed so highly cut off in the middle of life far from home and family. James Aull, who accompanied Colonel Owens, took charge of the merchandise and offered it for sale in Chihuahua. Not mistrusting the perfidy of the Spaniards, he was murdered while quietly engaged in business and alone in his store. Much of his goods were stolen. Thus ended the lives of two as good men as ever lived in Jackson County. James Aull was one of the most unassuming gentlemen ever met with, and his and Mr. Owens’ names will never be forgotten as long as Independence and Jackson County exist.”

From the close of the Mexican-American War to 1857, Independence was an important outfitting point for western caravans. The manufacture of wagons and other equipment needed by travelers was a profitable business. Some of the men engaged in the trade were Lewis Jones, Hiram Young, John W. Modie, and Robert Stone. The commerce of Independence was seriously affected when the Missouri River flooded in 1844 and washed away the boat landing at Wayne City. Later, John C. McCoy, considered the “Father of Kansas City,” gave this account of the outfitting business in Independence:

“Independence in those early years was selected as a place of arrival and departure and as an outfitting place for trappers and hunters of the mountains and western plains. It was well worth the while to witness the arrival of some of the pack trains. Before entering, they let us know of their coming by the shooting of guns so that when they reached Owens and Aull’s store, a goodly number of people were there to welcome them. A greasy, dirty set of men they were. Water surely was a rare commodity with them. They little cared for it except to slake their thirst. Their animals were loaded down with heavy packs of buffalo robes and peltry. Occasionally, they had a small wagon, which, after long usage, had the spokes and felloes wrapped with rawhide to keep the vehicle from falling to pieces.”

“So accustomed were they to their work that it took them little time to unload the burdens from the backs of the animals, store their goods in the warehouse. The trappers let the merchants attend to the shipping. The arrival in Independence was always a joyous ending of a hazardous trip, and when once safely over it, they were always ready for a jolly good time, which they had to their heart’s content. They made the welkin ring and filled the town with high carnival for many days.

“The mountain trade at length gave way to the Mexican trade — this being on a much larger scale. Pack mules and donkeys were discarded, and wagons drawn by mule and ox teams were substituted in their place. Such men as ‘Doc’ Waldo, Solomon Houke, William and Solomon Sublette, Josiah Gregg, St. Vrain, Chavez, and others of like character were early adventurers, and as the governor gave permission to them to enter and trade with the people, they ventured across the plains regardless of the dangers.”

While Francis Parkman, an American historian, and author, was in Westport, Missouri, in the spring of 1846, making preparations for a western journey, he visited Independence and provided this account of his visit:

“Being at leisure one day, I rode over to Independence. The town was crowded. A multitude of shops had sprung up to furnish the emigrants and Santa Fe traders with necessaries for their journey, and there was an incessant hammering and banging from a dozen blacksmith’s sheds, where the heavy wagons were being repaired, and the horses and oxen shod. The streets were thronged with men, horses, and mules. While I was in town, a train of emigrant wagons from Illinois passed through to join the camp on the prairie and stopped in the principal street. A multitude of healthy children’s faces were peeping out from under the covers of the wagons. Here and there, a buxom damsel was seated on horseback, holding over her sunburnt face an old umbrella or a parasol, once gaudy enough but now miserably faded. The men, very sober-looking countrymen, stood about their oxen; and as I passed, I noticed three old fellows who, with their long whips in their hands, were zealously discussing the doctrine of regeneration. The emigrants, however, are not all of this stamp. Among them are some of the vilest outcasts in the country.”

To hold the overland trade that had begun to shift to Westport and other upriver towns, Independence, in 1849, built a railroad to Wayne City three and one-half miles north on the Missouri River. Known as the Independence & Wayne City, or Missouri River Railroad, it was the first railroad constructed west of the Mississippi River. Architect William Singleton designed a road with cut and crushed stone, wooden ties, and iron-capped rails. The four-wheeled flat cars, drawn by teams of mules or oxen, carried passengers and freight from the steamboat landing to Independence Square, 4½ miles from the river. The train made a quarter turn on a turntable in the middle of the street before entering the elaborate two-story brick station. Unfortunately, the Independence & Missouri River Railroad went bankrupt in 1851, its station became a warehouse or livery stable, the turntable was buried in the street, and the wooden rails were left to decay.

The first overland mail route west of Missouri was established in 1850, between Independence and Salt Lake City, Utah, a distance of 1,200 miles. James Brown was given a government contract. The government awarded another contract to David Waldo, Jacob Hale, and William McCoy the same year to carry the mail from Independence to Santa Fe, New Mexico. The first regular United States mail taken across the Missouri border left for Salt Lake City on July 1, 1850, strongly guarded against Indian attacks. The undertaking was regarded as extremely hazardous at that time, and when the mail carriers returned safely the second month, the event was celebrated in Independence with much rejoicing. The men successfully fulfilled their first four years’ contract, demonstrating that mail service to Santa Fe and other points in the West was practicable.

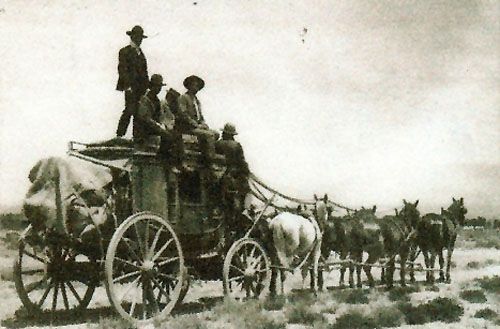

Express Stagecoach

The firm of Hockaday and Hall made this announcement of a new stage line in the Western Journal of Commerce in Kansas City in 1857:

Santa Fe traders and those desirous of crossing the plains to New Mexico are informed that the undersigned will carry the United States Mail from Independence to Santa Fe for four years, commencing on the first day of July 1857, in stages drawn by six mules.

- The stages will leave Independence and Santa Fe on the first and fifteenth of each month. They will be entirely new and comfortable for passengers, well guarded and running through each way, from twenty to twenty-five days. Travelers to and from New Mexico will doubtless find this the safest and most expeditious, and comfortable, as well as cheapest mode of crossing the plains.

- Fare through: From November 1st to May 1st, $150.00; from May 1st to November 1st, $125.

- Provisions, arms, and ammunition furnished by the proprietors.

- Packages and extra baggage will be transported when possible to do so, at the rate of twenty-five cents per pound in summer and fifty cents in winter, but no package will be charged less than one dollar.

- The proprietors will not be responsible for any package worth more than fifty dollars unless contents given and specifically contracted for, and all baggage at all times at the risk of the owner thereof.

- In all cases, the passage money must be paid in advance, and passengers must stipulate to conform to the rules which may be established by the undersigned for the government of their line of stages and those traveling with them on the plains.

- No passenger allowed more than forty pounds of baggage in addition to the necessary bedding.

- Mr. Levi Spiekleburg, at Santa Fe, and J. & W. R. Bernard & Company, at Westport, Missouri, and our conductor and agents are authorized to engage passengers and receipt for passage money.

But, for Independence and its jumping-off and supply point for westbound travelers, the end was close with the coming of the Civil War. Tensions between Kansas and Missouri before the Civil War, known as Bleeding Kansas, made the area unsafe for travel, and westbound traffic began to depart from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Several conflicts occurred in Independence during the Civil War. The town was raided by Union cavalry in 1861 and was occupied by Union troops in 1862. William C. Quantrill, the Confederate guerrilla, made a dash into the town in the spring of 1862. The Union garrison in Independence, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel J. T. Buell, was attacked on August 11, 1862, by a Confederate force of 600 to 800 men. The city was captured, and 350 prisoners were taken. The Confederate victory was costly, however, resulting in the death of ten experienced officers, among them Colonel John T. Hughes, and the wounding of Colonels Hays and Thompson.

Federal troops later reoccupied the town, and Southern sympathizers were expelled on August 24, 1863. The town was reoccupied by Confederate General Sterling Price on October 20, 1864, but was retaken four days later by Union General Alfred Pleasanton. General Robert E. Lee’s surrender in 1865 did not bring immediate peace to Independence; however, a law and order association, organized on July 14, 1866, was able to suppress violence and restore quiet. The war took its toll on Independence, and the town could not regain its previous prosperity, although a flurry of building activity took place soon after the war. The rise of nearby Kansas City also contributed to the town’s relegation to a place of secondary prominence in Jackson County. However, Independence has retained its position as the county seat to the present day.

Independence, Missouri

Independence continued to grow, and in 1890, when future president Harry S. Truman was just six years old, his family moved him there so that he could attend the Presbyterian Church Sunday School. Truman did not attend a traditional school until he was eight. After graduating high school in Independence in 1901, Truman held various clerical jobs until he entered the army in 1917 during World War I. The war was a transformative experience that brought out Truman’s leadership qualities. Before long, he entered politics, becoming an elected judge of the Court of Jackson County, Missouri, in 1922. Twelve years later, in 1934, he was elected as a U.S. Senator and in 1945 became President of the United States. While residing in Washington, D.C., his home at 216 North Delaware served as his summer White House. After two terms as President, he and his wife returned to Independence.

There is much to see and do in Independence — from unique shops to 13 heritage sites that paved the future of our country. The former President and First Lady Bess Truman are buried in the city. The Harry S. Truman National Historic Site (Truman’s home) and the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum are both located in Independence, as is one of Truman’s boyhood residences.

Independence continues to be important to the Latter-Day Saints and is the headquarters of the Community of Christ, the second-largest denomination in the Latter-Day Saint movement. This church built a temple, maintains a large auditorium, and a sizable visitors’ center, located directly across the street from the original Temple Lot designated by Joseph Smith in 1830. The lot is occupied by a small white-frame church building that serves as the headquarters and local meeting house for the Church of Christ (Temple Lot).

Today, Independence is the fourth-largest city in Missouri, with a population of more than 120,000. Most of Independence, which is a satellite city of Kansas City, lies within Jackson County, with a small portion of the city lying in Clay County.

Its rich heritage can be seen at many attractions throughout the city, including the National Frontier Trails Center, several historic homes, Independence Square, the spot where countless thousands of pioneers and emigrants outfitted themselves for their journey west, Civil War markers, and more.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America updated July 2023.

Also See:

Santa Fe Trail – Pathway to the West

Sources:

National Park Service

Santa Fe Trail Association

Visit Independence

Wikipedia