Moonlight anywhere is a delight. But there’s no moonlight in the world that can compare with the moonlight in Grapevine Canyon, our desert canyon, where the Castle stands.

— Bessie Johnson, 1932

Hidden in the green oasis of Grapevine Canyon in far northern Death Valley, California, the Death Valley Ranch, or Scotty’s Castle, as it is more commonly known, is a window into the life and times of the Roaring ’20s and the Great Depression of the ’30s. It was an engineer’s dream home, a wealthy matron’s vacation home, and a man of mystery’s hideout and getaway.

(Editor’s note: The National Park Service closed Scotty’s Castle for repairs after a flash flood in 2015 severely damaged the property, and then a later fire. As of this update, NPS says access to the Castle and Grapevine Canyon areas is prohibited unless part of a ticketed Tour. See their website HERE)

Walter Scott, better known as Death Valley Scotty, convinced everyone that he had built the castle with money from his rich secret mines in the area. However, Albert Mussey Johnson built the house as a vacation getaway for himself and his wife, Bessie. Scotty was the mystery, the cowboy, and the entertainer, but he was also a friend. Albert was the brains and the money. Two men as different as night and day, from different worlds and with different visions, who shared a dream.

In 1904, Walter Scott was in Chicago, Illinois, seeking backers for his legendary gold mines when he conned millionaire businessman Albert Johnson into investing. Despite receiving no return on his investment, even after the person he sent to the desert to check on Scott reported that there was no gold mine, Albert Johnson continued to invest in Scott. In 1906, Johnson himself went to California to visit him. Although he found nothing in the way of gold mines and endured Walter Scott’s great hoax, now known as the “Battle” of Wingate Pass, the dry weather and outdoor life proved beneficial to his health.

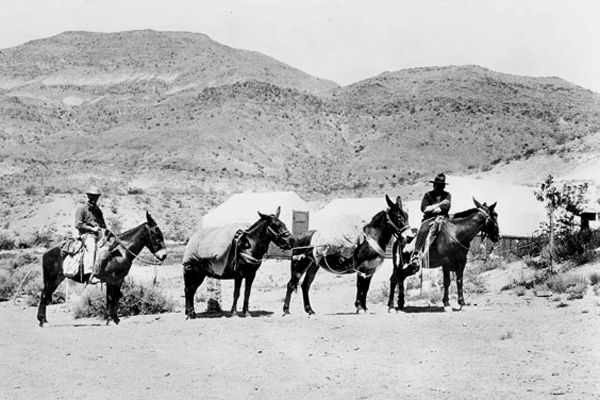

Between 1906 and 1922, Johnson visited the area about a half dozen times. Scott always met Johnson upon his arrival and acted as his guide. The two men would camp in canvas tents and tour the barren desert wilderness of Death Valley by horseback. Albert’s visits were often a month long.

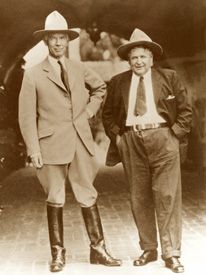

Albert Johnson

At first, his interests were primarily focused on the many mining claims he had either invested in or had heard about. At some point, however, his interest in the area became much more personal. His business life and the brutal Chicago winters were exhausting, and he often felt a desperate need for complete rest and change. A stay in the desert always proved tremendously beneficial for his health, relieving many of the ailments caused by a 1899 railroad accident.

Johnson began purchasing property in Grapevine Canyon in 1915. Within two years, he had purchased several hundred acres, would purchase more over the years, and fulfill the requirements prescribed by the Desert Land Act of 1871 to acquire another 1200 acres. The Act required a minimum amount of irrigation and a certain degree of improvements to the land before it could be rightfully claimed. By 1929, Johnson’s developments and improvements of the 1200 acres in question were completed, and his claim to the land was secured. In the end, the land, totaling some 1,500 acres, comprised two separate parcels about eight miles apart, referred to as the Upper and Lower Ranches.

Albert’s wife, Bessie Johnson, would later write: “What had started as a business expedition to inspect some mining claims transformed into a regular seasonal vacation and ultimately into a ten-year building campaign. The subtle allure of the desert combined with the captivating companionship of the likable Walter Scott, known to the public as Death Valley Scotty, persuaded Albert to forsake the luxuries of a marble mansion on the shores of Lake Michigan.”

That alone does not fully explain what was, to say the least, such an eccentric decision. Most published accounts center on Johnson’s friendship and attachment to Walter Scott as the central factor in his decision to locate here. No doubt that played an important part, for Scott introduced Johnson to the area. Johnson had been one of several investors in a series of phony mining propositions that Scott, a huckster and charlatan by trade, was habitually concocting. In 1906, Johnson made his first trip to Death Valley to inspect the mines Scott had convinced him existed. The state of Nevada and the entire region were then undergoing their last great mining boom due to silver strikes in the Goldfield and Tonopah areas, neither of which was far from Death Valley. The two men traveled extensively together by mule and horseback, investigating mines throughout the region. Not long after his first visit, Johnson realized the truth about Scott.

But, even after Johnson realized that Scott had lied and cheated him, he continued to befriend him. Perhaps Johnson envisioned Scott as one of the last romantic figures engendered by the Wild West, or maybe Johnson was utterly enraptured with the stories and tall tales Scott was so expert at telling. Despite a rather scurrilous reputation, Johnson felt that Scott “was absolutely reliable, and I don’t know of any man in the world I would rather go on a camping trip with than Scott.” Although Scott’s involvement in all phases of construction was minimal, he was an almost permanent resident of the Ranch and always a welcome guest of the Johnsons.

To say that the two men were opposites is an understatement. Albert Johnson was born into a wealthy family in Ohio. He was raised to be devoutly religious and never swore, smoked, or drank liquor. After graduating from Cornell University with a degree in civil engineering, he married Bessilyn Morris Penniman. He went on to make his fortune in the corporate world of finance and big business. In 1899, Johnson and his father were involved in a terrible train wreck. Johnson’s father was killed instantly, and Albert’s back was broken. He was immobilized and bedridden for 18 months. Eventually, he recovered but was left permanently crippled.

Scott was born and raised on a working Kentucky horse farm. At the early age of eleven, Scott ran away from home to join his two brothers, employed as ranch hands in Humboldt Wells, Nevada. After working as a water boy for a survey team and running mules for the Harmony Borax Mines in Death Valley, Scotty worked for twelve years as a rough rider in the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show. He eventually moved back to Death Valley, established a camp near Grapevine Canyon, his favorite part of the valley, and adopted it as his home. Whatever the basis for their relationship, the two men continued to hike and camp together, and Johnson could always count on Scott to meet him with horse and pack, ready to go.

Besides their abiding friendship, other factors played a role in Johnson’s decision to build a “Castle” in a countryside that most would have considered uninhabitable. Johnson and his wife came to appreciate and prize the protection afforded by such uninhabited land. She would later say: “We had traveled along through the sage for three hours and had seen no one. Even to this day, we often travel 150 miles on good roads and never see a soul or pass a car. This is one of the charms of the Desert after fighting your way through city traffic. The peace of it is such a joy after the turmoil of life outside. The mountains are fortresses of protection.”

Until 1921, Johnson had made his month-long trips to the desert a regular spring pilgrimage. He always looked forward to the chance to leave behind the worries and demands of high finance, but generally found it hard to get away. The year 1921 proved to be financially mixed. At the same time, the National Life Insurance Company, of which Johnson was president, had its best year ever, and another company he was also president of, North American Cold Storage, lost over $150,000. The loss of such a sum left Johnson depressed and resulted in a loss of confidence. While he was in this frame of mind, making split-second business decisions required of a man in his position was harder.

To relieve his feelings, he took some time off to travel. After a one-week vacation up north in September 1921, Johnson wrote to his sister Cliffe describing how he had felt renewed and what he hoped for the future. “The little week’s trip I had away showed me how tired I was and how much I needed a change and a rest. It is a long pull and a steady strain, with responsibility and detail every day that wears you out, but things are in pretty good shape now, and I am going to try to be away a little more this coming year.”

Johnson and Scott in Death Valley.

A few days later, Johnson informed his sister that he was going on a month-long trip, with his final stop in Goldfield, Nevada, 60 miles away, the closest town of any size to his property in Death Valley. “This is hardly a pleasure trip but more of a business trip, as there are several things I want to look over, and we are going to make some changes on the ranch.” The letter does not say who the “we” refers to or what kind of changes Johnson had in mind.

In 1922, Johnson built a few crude structures to make his seasonal visits to the area more comfortable for him and his wife, Bessie. In the fall of that year, Johnson hired Frederick William Kropf to be his construction superintendent and live and work on his ranch. Kropf, trained as a carpenter in Utah, oversaw all facets of construction of the first three structures — a garage, a large two-story main house, and a cookhouse. They would all have flat roofs and white stucco finishes.

The work proceeded slowly at first, with only a few men employed. Within a year, a crew of approximately 30 men lived and worked at the site. Most were Indians native to the area and were either Shoshone or Paiute. The remainder were white, generally skilled in a particular trade, such as carpentry, masonry, or plastering, and recruited by Kropf in Los Angeles, California. The entire crew was divided into teams, each assigned a different task. For instance, one team would do all the lathing and plastering, and another would truck and wash all the sand and gravel. Kropf was also a firm believer in unions and maintained an eight-hour day and a six-day work week as the standard schedule.

Due to the extreme summertime temperatures, construction was generally suspended in June and July. Almost all the building materials, such as lumber and cement, were shipped by train and delivered to Bonnie Claire, Nevada, a railroad siding on the Tidewater & Tonopah Railroad line, about 20 miles northeast of the construction site. From there, they were hauled over poor dirt roads by the Ranch’s trucks to the Ranch itself. All the construction work was accomplished manually with hand tools. Walter Scott’s mules pulled a Fresno scraper for almost all the excavation and grading work necessary for these earliest structures.

Once the main building was finished, the Johnsons took residence in the upstairs apartment. Conditions were still comparatively primitive compared to what the Johnsons were accustomed to in their Chicago home and what Albert thought proper and fitting for his wife, so he often visited without Bessie. Scott moved from his shack and occupied the room on the ground level just below the Johnsons’ apartment. This freed the shack Scott used for other employees’ occupancy.

Whenever Johnson was at the ranch, he became deeply interested and involved in every aspect of construction. He constantly gave Kropf verbal instructions on what he wanted done. Scott’s responsibilities regarding construction were minimal. For the first year, Scott cooked all the meals provided to the white crew. Melba, Kropf’s daughter, was hired in August 1923, when the number of employees was increasing, to replace Scott as a cook. One of the rooms in the north end of the garage, the first building to be finished, was used as a kitchen. Melba lived in the storeroom next to the kitchen in the garage.

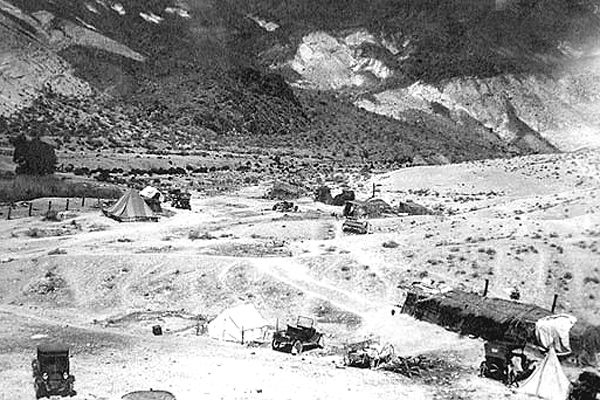

Kropf and his son, Milton, poured a concrete floor and shared one of the “tie shacks” left behind by the original owner. Still a young boy, Milton helped fill out the payroll and monthly progress reports and sent them to Johnson’s personal secretary, Miss Devlin, in Chicago. Johnson provided all the white men with housing, usually canvas tents or crude temporary structures. Room and board were deducted from everyone’s wages. The Indians provided their housing, which consisted of either tents or wickiups. They did not pay for room and board, but their wages were usually lower.

Johnson insisted that the two groups of men live separately in thoroughly segregated camps. The Indian camp was usually farther up the canyon and beyond the limits of Johnson’s property, where the white workmen generally resided. Johnson did not allow alcoholic drinking and forbade the visitation of the Indian camp by any white man. If caught, the perpetrator was fired. It is unknown why he was insistent upon the latter provision or which group he sought to protect.

Every day that Bessie was at the ranch, she held religious services that all the white men were required to attend. Its location varied throughout the grounds. Although Albert was gaining a national reputation as a preacher, only Bessie would deliver the sermons at the Ranch. Kropf, raised as a Mormon, once interrupted Bessie and said, “For a change, we would like to hear some concepts from some other religion. We will hear from this fellow.” It is not certain if this was the cause, but it was not long afterward that Kropf was let go. His services were terminated in July 1924. Melba had been fired three months earlier over a disagreement with Bessie.

In the winter of 1924, Johnson tried to find a replacement for Kropf and sought out Matt Roy Thompson. Thompson had been a friend of the Johnsons for quite a long time. He had first met Bessie while they were both students at Stanford University. Because of the losses his family incurred in the Panic of 1893, Thompson was forced to leave school. At approximately the same time, Bessie transferred to Cornell, where she met and eventually married Albert. Thompson and the Johnsons stayed in touch infrequently over the years. When the Johnsons contacted Thompson, he was employed by the Interstate Commerce Commission as a land appraiser.

Thompson traveled to Chicago to discuss the project. Johnson offered him the position, and then Thompson accompanied the Johnsons to Death Valley to see firsthand what the project entailed. Thompson requested a one-year leave of absence from his current position. His request for leave was granted, and he accepted the position as general superintendent at the Death Valley Ranch. Thompson expected to resume his activities with the Interstate Commerce Commission after only a year in Death Valley. However, as plans and his involvement grew, so too did his commitment to the project. He stayed in Johnson’s employ for the next six years.

Thompson assumed his duties at the Ranch in October 1925. The stables, chicken coop, and workshop/shed were all under construction when Thompson started work. They probably started after Kropf had left, meaning construction had continued without an on-site supervisor for approximately 1 year. By the time Thompson arrived, the stables required only a few finishing touches before they were completed. Construction of the long shed had started, but required much more work and was one of the first significant projects Thompson oversaw. The chicken coop was nearing completion when Thompson arrived on the site. By the time it was almost finished, it was decided to use it for housing instead, and it became known as the “bunkhouse.” A chicken coop was then located in the long shed. All three of these buildings were designed by Albert Johnson. By 1924, a separate Cook House was completed, devoted to preparing meals for the white crew. Besides a kitchen, it included a dining room for the men and a bedroom for the cook. Since all the preparation, cooking, and eating of meals now took place exclusively in the cookhouse, the storeroom and cook shack at the north end of the garage were no longer necessary. They were converted and used instead as Thompson’s office and private apartment.

Thompson’s first project was a one-story building parallel to the north of the main building. In January 1926, Thompson went to Los Angeles to recruit additional workers for this building. It was to be made entirely of concrete and would serve various purposes. Originally known as the “Cellar,” it later took the name of one of its principal rooms, becoming the “Commissary” or “Commissary Building.” The Commissary itself served as a storeroom for foodstuffs and other general supplies. A large, open-air room in the center of the structure sheltered a work area for construction machinery and later served as a garage for automobiles. The room to the west became the “Power Room,” where a Pelton water wheel would drive a small electric generator.

It was close to that point that a reporter visited the ranch. An article in the March 1926 issue of Sunset magazine described the buildings at the Ranch as follows:

“Already there is a two-story building of concrete construction [the main house], with screened-in sleeping quarters, luxurious bathrooms, and expansive dining quarters. There is a garage that houses three trucks and two passenger cars, with sufficient space to accommodate a fire department. There is another enormous building [stables] that shelters the mules used for development work. And Scotty is building a plant [the Commissary Building] to generate electricity by the use of power that comes from spring water flowing from higher ground.”

This is only one of the many period articles that mention Scott as the main protagonist. The activity at the Ranch, combined with its unusual location and word of it, began to travel far and wide. Ironically, the Johnsons chose this location to escape the crowds and pressures of the city. They certainly did not mean to attract the attention of the curious public. The lavishness they sought in their new home was not meant to impress strangers or the public at large but only to please themselves and to ingratiate those few individuals they invited there as guests. That being the case, it is not so hard to understand why the Johnsons allowed Scott to claim the building as his.

Scott was a character who loved to be center stage. He practically thrived on it. Neither Albert nor Bessie cared for that kind of attention. Albert deliberately kept his name out of the newspapers and began relying on Scott to handle all publicity. Albert must have realized that he would need a front if he were ever to evade the public’s growing scrutiny. When asked by a reporter about his relationship with Scott and the ranch, Johnson reportedly said, “I’m only his banker.” Although Scott had practically nothing to do with any part of the construction, Johnson continued to allow Scott to serve as the figurehead for the entire operation. Friends of the Johnsons and those who worked there knew the truth, but most of the public was kept unaware. The sham was so convincing that even today, it becomes hard to separate fact from fiction.

Not long after construction began at the Ranch, Johnson began thinking about hiring a professional architect to design something more splendid and appealing. Though he considered Frank Lloyd Wright, he chose Charles Alexander MacNeilledge. On June 4, 1926, the two men entered into a contract, the stipulations of which required that MacNeilledge be paid a $1,000 flat fee in return for the… “designing and preparation of sketches and detailed working drawing, sufficiently detailed to enable my carpenters and other workmen on the job to erect buildings according to your sketches, and also including the purchasing and bills of material for the Redwood lumber, hardware, electric light fixtures, etc. required for my main house or residence with attached porches and pergolas, etc., located in Grapevine Canyon, Death Valley, Inyo County, California.” The quote suggests that some of the basic design elements that make the ranch unique were already decided upon at this point, particularly the use of specific materials and the emphasis on metal hardware and custom-made lighting fixtures.

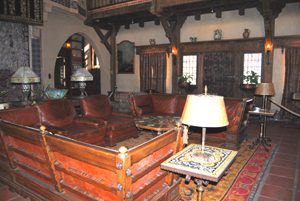

The style chosen for the Valley Ranch complex can be described in several ways. Some have called it the Spanish Colonial Revival; others, Spanish Mediterranean. Others have said the Ranch was modeled after a Spanish Villa or Hacienda, while others still have preferred to cite its Spanish Moorish influences. Bessie Johnson liked to call it “Spanish Provincial.” Albert Johnson followed the lead established by the architect himself, who termed it “The Spanish Style.”

Working conditions under Construction Superintendent Thompson varied. An eight-hour day was the standard for the first several years under his supervision. In March 1929, however, a nine-hour day was instituted, and several Indians quit in response. The construction season varied somewhat from year to year. Generally, the Indians began work in September, and the white crew began in October. Construction was temporarily suspended for 2 to 4 weeks each year due to summer heat. Sometimes the winter cold or heavy snow would force Thompson to halt work until conditions improved. Winter shutdowns of this type did not occur every year and typically lasted no more than a week.

Indian camp at Scotty’s Castle in 1926.

The strict segregation between white and Indian employees continued to be rigorously enforced. Any white found visiting the Indian camp was immediately fired. Living conditions between the two groups varied to a degree. Room and board, including three meals a day, were provided for all white employees, the cost of which was deducted from their wages. Most men lived in crude, temporary structures made of whatever was available, such as corrugated sheet metal. Often, however, there was not enough housing to accommodate everyone, and some men were forced to sleep outdoors. The Indians, however, provided their own tents or wickiups and established their camp just beyond the boundaries of Johnson’s land, whose location varied from year to year. They must also have provided their own food, as no deductions are recorded in the weekly payroll. They sometimes purchased food and sundry items from Thompson, but only irregularly.

For a few years at least, the Ranch supplied itself with fresh eggs and raised its own turkeys and chickens. The remainder of the food supplies were shipped by train to Bonnie Claire, Nevada, from either Tonopah, Nevada, or Los Angeles, California. There were no cows on the Ranch, so all the milk they used was from a can.

Johnson vehemently opposed any drinking at the camp. There were, however, three incidents when the problem of carousing and drinking was so extreme that a whole group of men, both white and Indian, was fired, and the entire camp was closed down temporarily.

In September 1930, Johnson imposed further restrictions on all those working for him. Thompson reported the following on the implementation of Johnson’s wishes.

“All employees have signed a new working agreement, including a clause permitting us to inspect all cars leaving camp, and also to the effect that men interested in prospecting will not be retained on the job. No men under 24 years old are employed, and we have cut off the aged ones, as per our talk.”

Why Johnson felt all these precautions were necessary is unclear. Nonetheless, Johnson was aware that the Depression put many men, especially in the building trade, out of work and that the situation could be worked to his advantage. In fact, Johnson had the present crew fired and an almost entirely new workforce hired in September 1930 to reduce the pay rate for each position. Superintendent Thompson reported to Johnson:

“The work started up in full force again yesterday morning, at a total reduction in wages amounting to more than $25.00 a day under last season’s schedule. Carpenters are now getting $6 a day and board, and Indians $3 without board. Other men have been reduced in proportion, and all seemed to take the reduction in good spirits.”

The work crew at Scotty’s Castle

The firing of one crew and the hiring of another was repeated in February 1931 to again take advantage of the falling wage scales due to the Depression. The turnover of employees was incredibly high, to the point that Scott, more the frontman and astute witness than the participant, had been known to say that it took three crews to make any progress: one coming, one going, and one working.

In the late 1920s, proposals to make Death Valley a component of the National Park and Monument system were increasingly coming to the forefront. On July 25, 1930, President Herbert Hoover signed an executive order withdrawing over 2 million acres of land from the public domain pending the outcome of further park studies. Within months, U.S. Government surveys were mapping the as-of-yet-uncharted lands within the valley. The survey team, headed by U.S. Transitman Roger Wilson, used Ranch as a base camp and supply station, often purchasing food and equipment from Thompson.

Wilson kept Thompson informed of the survey’s progress and findings. In December 1930, Wilson apprised Thompson of an “unexpected situation” that “might throw the new township line right through the main house instead of a half-mile south of it.”

The following January, Wilson explained to Thompson in great detail precisely what the situation was, and Thompson immediately recounted it to Johnson.

“Mr. Roger Wilson, U. S. Transit man, was just in and explained to me the status of the survey. He says that under his present instructions, the survey will place the township line north of the main house about one-half mile, thus making all the improvements fall into the Park limits. This situation is caused by the wide discrepancy between Surveyor Bond’s Saline Valley survey of 1880 and Surveyor Baker’s Death Valley survey of 1884, which latter survey throws every corner one mile north and one mile west of where the corners would be if the 1880 survey were projected easterly. The 1884 survey is so incorrect that it might be advisable to throw it out entirely and bring in new lines from the 1880 survey from Saline Valley, but this cannot be done without instructions from the higher officials in the land department at Washington D.C... If you could influence the General Land Office in Washington to order this to be done, it will straighten out the situation here so that the Saline Valley survey will govern and thus throw all the improvements north of the park boundary line. But, Mr. Wilson says that this will have to be done quickly to have any change made in his present surveys.”

Over the next several weeks, Johnson met with several authorities to determine the outcome. Such uncertainty about the land’s continued ownership must have led Johnson to rethink his plans for the Ranch. In February 1931, Johnson instructed Thompson to close the camp for two weeks and meet him in Los Angeles to discuss operations at the Ranch. One specific goal was to establish a lower wage scale for all workers at the Ranch. Thompson investigated present wage scales in the Los Angeles area and believed they could get workers of the same or better quality and save $50 a day.

An entirely new crew would replace all those presently working. This included the dismissal of the architect, Charles Alexander MacNeilledge. The connection between the problems with land ownership and MacNeilledge’s dismissal is unclear, but they indeed coincided. Perhaps Johnson felt constrained by time and money and wanted an architect to deliver his drawings more timely. Perhaps, even more simply, everything Johnson wanted or could hope to finish had been designed, and he no longer needed any additional design work performed.

Not too long after MacNeilledge’s dismissal and the hiring of an entirely new crew, construction ceased altogether. The final payroll was dated August 23, 1931. Although the most often-heard reason for the shutdown has been the effects of the Depression on Johnson’s finances, the uncertainty about Johnson’s continued ownership of the very land upon which he built seems a more likely explanation. The fact that both the gravel separator and the solar heater were greatly expanded in 1930, well after the stock market crash, seems sufficient to disprove that the immediate effects of the Depression caused the shutdown.

In February 1933, President Hoover signed a proclamation designating Death Valley as a National Monument, and the lands it encompassed included those of the Ranch. In August 1935, President Franklin Roosevelt signed a bill allowing Johnson the right to buy the land in question. The act’s provisions allowed Johnson to purchase the lands he thought were already his for $1.25 an acre. It was not until November 1937 that the patent was issued, and the 1,529 acres were purchased and exchanged. By this time, Johnson had lost most of his fortune and could not afford to resume construction anew.

The Depression did not immediately affect Johnson’s fortunes and did not directly cause the sudden and final cessation of construction. In fact, four years after the Wall Street crash, the nation’s economic conditions caught up with him and his project. In 1933, the National Life Insurance Company went into receivership. Johnson had invested a large proportion of the company’s assets in banking, an activity that was hit especially hard in the 1930s. National Life had purchased over 12,000 shares of Continental Illinois, and Johnson was one of its directors. Shares of Continental sold for as high as $1,400. After the crash, it sold for as little as $17.11

The heavy investment Johnson made in a rayon factory in Burlington, North Carolina, only compounded matters. The plant, under construction for several years, never opened and never produced a yard of fabric. The two million dollars Johnson invested, including both personal and company funds, failed to return a single cent. Much of the money used to finance the rayon venture came from National Life. When National went into receivership, the plant and the life insurance company were put up for auction.

National was eventually awarded to Sears, Roebuck, and Co. and renamed Hercules Life. The plant was included in the exchange. Some explanations claim that Johnson’s fascination with the Castle, the desert, and the isolation they afforded him caused his economic downfall. Johnson had built his hideaway in such an eccentric location because he did not want neighbors and regularly felt the need to escape the constant pressures of the business world. Johnson’s absences from Chicago were keenly felt at the office. The Castle had no telephone, and the nearest telegraph station and post office was 25 miles away in Bonnie Claire, Nevada. Johnson could not be reached when matters of great importance surfaced at work. The company’s day-to-day management fell to those who were less able to handle the situation that arose. Some of those closest to Mr. Johnson felt sure that if he had attended more closely to business and had not been away so much of the time in California, he would have averted the collapse of National Life.

Although Johnson lacked a steady income once the life insurance company was sold, he did retain substantial private property holdings: the homes in Chicago and Hollywood, Shadelands Ranch, and of course, the Castle. His financial situation was serious enough that Johnson sold his home in Chicago and had to develop other sources of revenue. Still a man of excellent business acumen, Johnson capitalized on what he still had. The house in Hollywood became his principal residence but offered little income-producing potential. Although the Johnsons were to depend upon it more dearly for an income, the nut and fruit trees of the Shadelands Ranch, which Bessie had inherited from her parents, produced much as they had before the Depression. Only the commercial potential of the Castle itself was yet untapped.

In the 1920s, Death Valley was strongly promoted and developed as a tourist attraction. The fundamental requirement for the region’s success was its accessibility to the public. The growing popularity of the automobile as the public’s preferred choice of travel required building new roads and improving those already in place if the area’s potential as a public attraction was to be successfully exploited. Much of the land in Death Valley belonged to the U.S. Borax Company. When borax mining became less profitable, the company lobbied to designate the area as a national monument and began planning a luxury resort within the valley. Although Stephen Mather, then the director of the National Park Service, favorably received the idea of establishing Death Valley as a national monument, he was reluctant to act. Mather, himself a former borax executive, thought that if he personally advocated the company’s proposal too strongly, it would result in cries of foul play and favoritism. In January 1929, Horace Albright replaced Mather, who had resigned due to failing health. Although Albright, like Mather, had personal and professional connections with the Borax industry, Albright was less fearful of accusations of favoritism and proceeded quickly in proposing boundaries and drafting tentative legislation.

At much the same time, other, more minor interests were developing their projects. In May 1926, Herman William Eichbaum opened a 38-mile scenic toll road through Towne Pass and over the mountains bordering Death Valley to the west. The following November, Eichbaum opened his Stove Pipe Wells Hotel, approximately 40 miles south of Grapevine Canyon, on the Death Valley floor. Soon after that, the U.S. Borax Company financed the construction of the Furnace Creek Inn. It opened to the public in February 1927, 15 miles south of Stove Pipe Wells. New roads were also being promoted to the east, on the Nevada side of the Castle. By 1930, the first improved automobile road north through the valley and up towards Death Valley Ranch was nearly complete. Its effects were felt at the castle, as noted by Thompson in letters to Albert Johnson in March 1930.

“The two glaziers drove down the valley this afternoon on the road that Mr. Eichbaum has been grading. Mr. Eichbaum and his wife drove up this road from [their hotel] to the Ranch in 2 1/2 hours, and many cars are coming over it lately. The new Valley road makes it possible to run down to Los Angeles in nine hours.”

Road promoters often told people about the “Castle” to the north and urged them to see it for themselves. Not long after the road was improved, visitors, mostly uninvited, stopped by Death Valley Ranch for a quick look and sometimes more. The topic of “visitors” became a regular inclusion in most of Thompson’s progress reports to Johnson.

“Forty to eighty [visitors] nearly every day. We do not feed them, except rarely when Scotty gives certain ones a special invitation.”

The number of visitors grew as tourism became more popular and access by car became easier or less dangerous. Less than a year after the road was opened, Thompson reported to Johnson:

“There are about 100 visitors a day driving through here this weekend because of the double holiday… The two hotels in the Valley are turning dozens of people away each night.”

At some point, Johnson must have realized the financial promise these visitors held, for by 1934, tours of the Main House and Annex were being conducted informally. By 1936, tour guides were hired and trained, and an admission price of one dollar per person was instituted. More so than Albert, Bessie administered these tours and was known to conduct a few herself.

“We are now employing about a dozen young men and women under a resident manager to act as guides and guards. The girls are dressed in pretty frocks and make the visitors feel comfortable. Visitors range from a few a day to as high as 130.”

Johnson began selling mementos to supplement income from direct tour admission charges. Bessie had written a small anthology of stories about Walter Scott in 1932, entitled Death Valley Scotty by Mabel. In addition, she prepared a written guidebook for the tour of the Main House and Annex. It was intended to serve two separate functions: first, as a training manual for the many employees hired as guides, and second, as a keepsake for the paying public. Several sketches of the “Castle” by M. Roy Thompson were included to illustrate the text. In 1941, Johnson privately published 10,000 guidebooks under the business name Castle Publishing Company and sold them to the public as souvenirs. Afterward, Johnson stated:

“We placed the books on sale in the middle of this month [October 1941], so we have had only five days’ experience and not very many people going through the castle as yet, but we have averaged ten books a day. We are selling them at $1.00 each, so it looks as though we would sell at least 1/2 of the 10,000 by May 1.”

Although plans to publish Bessie’s anthology of anecdotes about Scott and her life in the desert were set, they never materialized, probably because of the intervening events of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the month following the first selling of the other pamphlet.

Albert Johnson also envisioned the potential financial value in postcards and hired professional photographer Burton Frasher to take dozens of large-format photographs. Frasher, working with their son Burton Jr., specialized in publishing postcards and often stayed at the Ranch, taking photographs of the buildings and grounds, as well as the scenery of the surrounding area. Hundreds of photographs of the Ranch were taken, and thousands of postcards were produced and sold. Many of Frasher’s postcards are still printed and available today in the gift shop at Scotty’s Castle.

Though attracting tourists to the Castle was becoming a success, Albert’s world would soon be turned upside down when, in 1943, his wife Bessie was killed in a car accident. The event occurred when he and Bessie went over a mountain pass some 40 miles south of the Ranch when Albert lost control of the car. Bessie was killed instantly. His sorrow over losing his wife and life-long companion, combined with Johnson’s deteriorating health, made it increasingly difficult for Albert to visit and adequately maintain the property. Making matters worse, gasoline and tires were strictly rationed during World War II, severely diminishing public visits to the Ranch. This resulted in a substantial loss in income, making the costs of continued maintenance even more challenging to meet.

In 1946, Johnson established the Gospel Foundation. The charity was organized to manage Johnson’s estate and to undertake certain social betterment functions. In 1947, Johnson inserted a provision in his will that all his landholdings would pass to the Foundation upon his death. Johnson transferred several properties to the foundation in his will. Besides the Death Valley Ranch, they would gain control of the Shadelands Ranch and the Hollywood home. Johnson died on January 7, 1948. One more provision in Albert Johnson’s will called for his friend, Walter Scott, to be cared for by the Gospel Foundation after his passing and to be allowed to stay at the ranch until his death. Walter Scott died in 1954 and was buried on the hill overlooking Scotty’s Castle next to a beloved dog.

The house in Hollywood was used as an office and headquarters. The hundreds of acres surrounding the house at Shadelands were slowly sold off, parcel by parcel. Death Valley Ranch had already been established as a motel and tourist site, and the foundation continued to run it as such. The shed was renamed the “Rancho,” and the Guest House was renamed the “Hacienda.” The Gospel Foundation divided the latter into four separate rooms and rented these out as well. The suites in the Castle itself were available for rent and, of course, went for premium prices: $13 a night with breakfast. At some point, the administration found they needed employee housing more than motel rooms, and they reconverted the “Rancho” for that purpose.

Despite the apparent success of the tours and lodging facilities, the Foundation wished to divest itself of ownership of the Castle. In 1970, the Foundation found an interested buyer in its neighbor, the National Park Service. The same year, the Foundation also donated Shadelands to the city of Walnut Creek for use as a historic house museum. These divestitures proved very beneficial for the foundation, which was awarded tax-exempt status once it no longer owned these properties. The National Park Service purchased the Castle and its lands for $850,000. By 1972, Scotty’s Castle was officially incorporated into Death Valley National Monument. The foundation still awards $400,000 in grants each year to needy, socially oriented causes.

Today, Albert and Bessie Johnson’s Death Valley Ranch is known as Scotty’s Castle. Located in Death Valley National Park, the house is no longer available to rent for the night, but visitors can still view the house and grounds. There is no charge to view the Upper Ranch grounds; however, there is an admission fee to tour the castle.

(Editors note: The National Park Service closed Scotty’s Castle for repairs after a flash flood in 2015 severely damaged the property and a later fire. As of this update, NPS says access to the Castle and Grapevine Canyon areas is prohibited unless part of a ticketed Tour. See their website HERE)

Contact Information:

Death Valley National Park

P.O. Box 579

Death Valley, California 92328

(760) 786-3200

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2025.

See our Death Valley Photo Gallery HERE

Also See:

Characters of Early Death Valley

Sources:

Death Valley National Park

Historic American Building Survey