O captain. My captain. Our fearful trip is done;

The ship has weathered every rack, and the prize we sought is won;

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring:

But O heart! Heart! Heart!

Leave you not the little spot,

Where on the deck my captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

O captain. My captain. Rise up and hear the bells;

Rise up–for you the flag is flung–for you the bugle trills;

For you bouquets and ribbon’d wreaths–for you the shores a-crowding;

For you they call, the swaying mass, their eager faces turning; O captain. Dear father.

This arm I push beneath you;

It is some dream that on the deck,

You’ve fallen cold and dead.

My captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still;

My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor win:

But the ship, the ship is anchor’d safe, its voyage closed and done;

From fearful trip, the victor ship, comes in with object won:

Exult O shores, and ring, O bells.

But I with silent tread,

Walk the spot the captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

–Walt Whitman

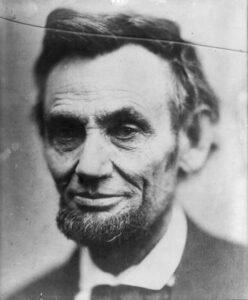

Leaving an enduring legacy in his historic role as the savior of the Union and emancipating the slaves, Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865.

Five months before receiving his party’s nomination for President, he sketched his own life, saying: “I was born on February 12, 1809, in Hardin County, Kentucky. My parents were both born in Virginia, of undistinguished families — second families, perhaps I should say. My mother, who died in my tenth year, was from a family named Hanks. My father moved from Kentucky to Indiana when I was in my eighth year. It was a wild region, with many bears and other wild animals still in the woods. There, I grew up. Of course, I knew little when I came of age. Still, somehow, I could read, write, and cipher, but that was all.”

He was the second child of Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, born in a one-room log cabin on the Sinking Spring Farm in Hardin County, Kentucky (now LaRue County). Though from humble beginnings, his father Thomas enjoyed considerable status in Kentucky—where he sat on juries, appraised estates, served on country slave patrols, and guarded prisoners. Thomas owned two 600-acre farms, several town lots, livestock, and horses by the time Abraham was born. He was among the wealthiest men in the county; however, in 1816, Thomas lost all his land in court cases due to faulty property titles.

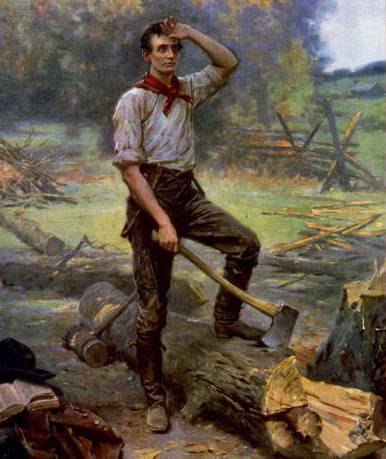

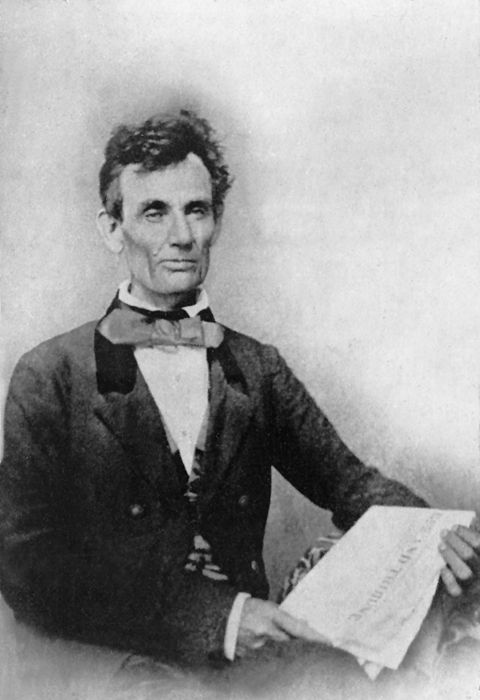

Abraham Lincoln as a Youth.

The family moved north across the Ohio River to Indiana when Lincoln was nine. His mother died of milk sickness in 1818, and his father remarried the following year. In 1830, fearing a milk sickness outbreak along the Ohio River, the Lincoln family moved west, settling in Illinois. At the age of 22, Lincoln struck out on his own, making extraordinary efforts to attain knowledge while working on a farm, splitting rails for fences, and keeping a store in New Salem, Illinois. He also held various public positions, such as postmaster and county surveyor, while reading voraciously and teaching himself law. Of his learning method, he would say: “I studied with nobody.” He became an Illinois congressman in 1834 and was admitted to the bar in 1836. He was a captain in the Black Hawk War, spent eight years in the Illinois legislature, and rode the circuit of courts for many years. His law partner said of him, “His ambition was a little engine that knew no rest.” He married Mary Todd on November 4, 1842, and the couple would have four sons, only one of whom lived to maturity.

In 1858, Lincoln ran against Stephen A. Douglas for Senator. He lost the election, but in debating with Douglas, he gained a national reputation that won him the Republican presidential nomination in 1860. In his Inaugural Address, he warned the South:

“In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to preserve, protect, and defend it.”

Lincoln thought secession was illegal and was willing to use force to defend Federal law and the Union. When Confederate batteries fired on Fort Sumter, South Carolina, and forced its surrender, he called on the states for 75,000 volunteers. As President, he built the Republican Party into a strong national organization. Further, he rallied most of the northern Democrats to the Union cause. On January 1, 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation that declared forever free those slaves within the Confederacy.

Lincoln won re-election in 1864, as Union military triumphs heralded an end to the war. The spirit that guided him was that of his Second Inaugural Address, now inscribed on one wall of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.:

“With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds.”

Just weeks later, on April 14, 1865, Lincoln was assassinated at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. by John Wilkes Booth.

“America will never be destroyed from the outside. If we falter and lose our freedoms, it will be because we destroyed ourselves.”

— Abraham Lincoln

Lincoln’s Story by Henry Cabot Lodge and Theodore Roosevelt in 1895

As Washington stands for the American Revolution and the establishment of the government, Lincoln is the hero of the mightier struggle by which our Union was saved. He was born in 1809, ten years after Washington; his work had been laid to rest at Mount Vernon. No great man ever came from beginnings that seemed to promise so little. Lincoln’s family had been sinking on the social scale for more than one generation. His father was one of those men found on the frontier in the early days of the Western movement, constantly changing from one place to another and dropping a little lower at each remove. Abraham Lincoln was born into a family that was not only poor but also shiftless, and his early years were marked by ignorance, poverty, and hard work. Out of such inauspicious surroundings, he slowly and painfully lifted himself. He educated himself, he took part in an Indian war, he worked in the fields, he kept a country store, he read and studied, and, at last, he became a lawyer. Then, he entered into the rough politics of the newly settled state of Illinois. He became a leader in his county and later served in the legislature. The road was very rough, the struggle was harsh and very bitter, but the movement was always upward.

At last, he was elected to Congress and served one term in Washington as a Whig with credit but without distinction. Then he returned to his law and politics in Illinois. He had, at last, made his position. All that was needed was an opportunity, which came to him in the tremendous anti-slavery struggle.

Lincoln was not an early abolitionist. His training had been that of a regular party man and a member of a great political organization, but he was a lover of freedom and justice. Slavery, in its essence, was hateful to him, and when the conflict between slavery and freedom was fairly joined, his path was clear before him.

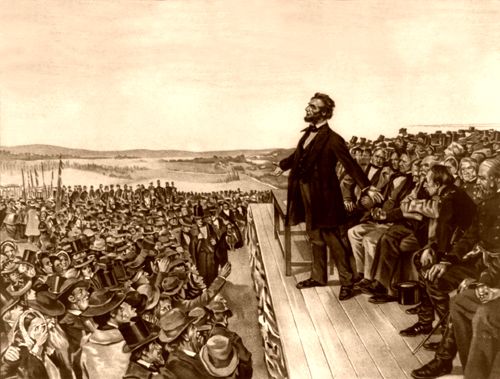

Abraham Lincoln while campaigning for the U.S. Senate, Chicago, Illinois.

He took up the anti-slavery cause in his state and made himself its champion against Douglas, the great leader of the Northern Democrats. He stumped Illinois against Douglas as a candidate for the Senate, debating the question that divided the country in every part of the state. He was beaten in the election, but his own reputation was built on the power and brilliance of his speeches. Fighting the anti-slavery battle within constitutional lines, concentrating his whole force against the single point of the extension of slavery to the territories, he had made it clear that a new leader had arisen for the cause of freedom. From Illinois, his reputation spread to the East, and soon after his great debate, he delivered a speech in New York that attracted wide attention. At the Republican convention of 1856, his name was one of those proposed for vice president.

When 1860 came, he was a candidate for first place on the national ticket. The leading candidate was William H. Seward of New York, the most conspicuous man on the Republican side. Still, after a sharp struggle, the convention selected Lincoln, and the great political battle came at the polls. The Republicans were victorious, and as soon as the voting results were known, the South began seceding from the Union. In February, Lincoln made his way to Washington, arriving secretly from Harrisburg to escape a threatened assassination attempt, and on March 4, 1861, he assumed the presidency.

No public man, no great popular leader, ever faced a more terrible situation. The Union was breaking, the Southern States were seceding, treason was rampant in Washington, and the Government was bankrupt. The country knew that Lincoln was a man of great capacity in the debate, devoted to the cause of anti-slavery and the maintenance of the Union. But no one knew his ability to deal with the awful conditions he was surrounded by.

To follow him through the four years of the Civil War that ensued is, of course, impossible here. Suffice it to say that no greater, no more complex a task has ever been faced by any man in modern times, and no one ever met a fierce trial and conflict more successfully.

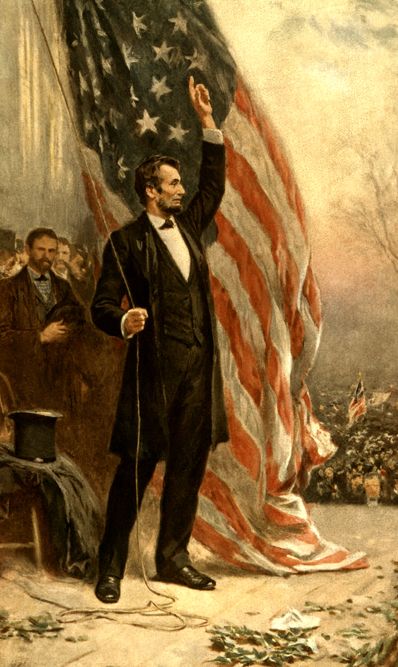

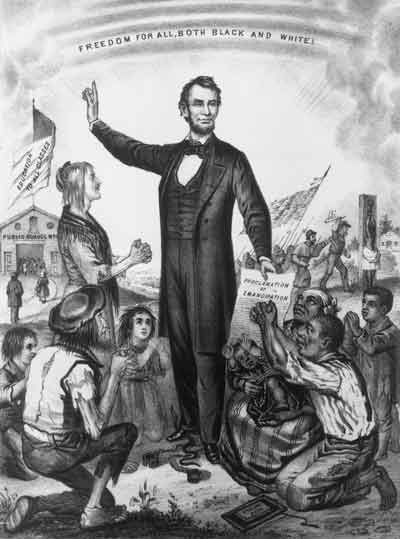

Abraham Lincoln Anti Slavery.

Lincoln put the Union’s question to the forefront and, at first, let the question of slavery drop into the background. He exerted every effort to hold the Border States with moderate measures, thus preventing the spread of the rebellion. For this moderation, the anti-slavery extremists in the North assailed him, but nothing shows more his far-sighted wisdom and strength of purpose than his action at this time. By his policy at the beginning of his administration, he held the border states and united the people of the North in defense of the Union.

As the war went on, Lincoln went on, too. He had never faltered in his feelings about slavery. He knew better than anyone that the successful dissolution of the Union by the slave power meant the destruction of an empire and the victory of the forces of barbarism. But he also saw what very few others at the moment could see, that if he was to win, he must carry his people with him, step by step. So when he had rallied them to the Union’s defense and checked the spread of secession in the border states, in the autumn of 1862, he announced that he would issue a proclamation freeing the slaves.

The extremists initially doubted him, and the conservative and the timid doubted him now. Still, when the Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863, it was found that the people were with him in that, as they had been with him when he staked everything upon the maintenance of the Union.

Battle of Bull’s Run (Manassas), Virginia, July 21, 1861.

The war went on to victory, and in 1864, the people showed at the polls that they were with the President and reelected him by an overwhelming majority. Victories in the field went hand in hand with success at the ballot box, and in the spring of 1865, all was over. On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Virginia, and five days later, on April 14, a miserable assassin crept into the box at the theater where the President was listening to a play and shot him. The blow to the country was terrible beyond words, for then men saw, in one bright flash, how great a man had fallen.

Lincoln died a martyr to the cause he had given his life to, and both life and death were heroic. The qualities that enabled him to do his great work are now evident to all men. His courage and wisdom, keen perception, and almost prophetic foresight enabled him to deal with all the problems of that distracted time as they arose around him. But he had some qualities, apart from those of the intellect, which were equally important to his people and the work he had to do.

His character, at once strong and gentle, gave confidence to everyone and dignity to his cause. His infinite patience and humor enabled him to turn aside many difficulties that could have been met in no other way. But most important of all was the fact that he personified a great sentiment, which ennobled and uplifted his people and made them capable of the patriotism that fought the war and saved the Union. He carried his people with him because he instinctively knew how they felt and what they wanted. He embodied all their highest ideals, and he never erred in his judgment.

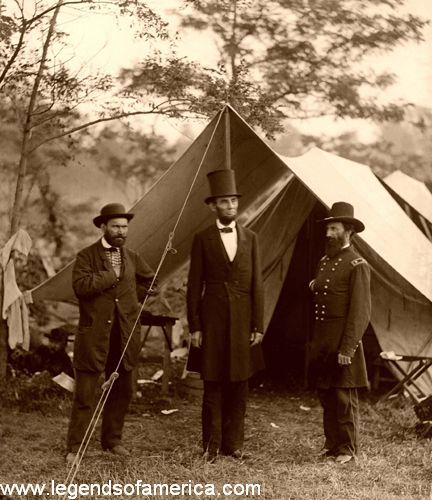

Allan Pinkerton, President Lincoln, and Major General John A. McClernand, 1862.

He is not only a great and commanding figure among history’s great statesmen and leaders, but he also personifies the sadness and pathos of the war, as well as its triumphs and glories. No words that anyone can use about Lincoln can, however, do him such justice as his own, and I will close this volume with two of Lincoln’s speeches, which show what the war and all the great deeds of that time meant to him, and through which shines the great soul of the man himself. On November 19, 1863, he spoke as follows at the dedication of the National Cemetery on the Battlefield of Gettysburg:

“Fourscore and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now, we are engaged in a great Civil War, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that the nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate–we cannot consecrate–we cannot hallow–this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract.

The world will little note or long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. Instead, it is for us, the living, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who have fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us–that from the honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

On March 4, 1865, when he was inaugurated the second time, he made the following address:

Fellow-Countrymen: At this second appearing to take the oath of presidential office, there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement, somewhat in detail, of a course to be pursued seemed proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of the great contest, which still absorbs the attention and engrosses the energies of the nation, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself, and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.

On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago, all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending Civil War. All dreaded it–all sought to avert it. While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war–seeking to dissolve the Union and divide effects by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let it perish. And the war came.

One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the conflict’s cause might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes his aid against the other. It may seem strange that any man should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered that of neither has been answered fully.

The Almighty has his own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offenses, for it must needs be that offenses come; but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must need come, but which, having continued through his appointed time, he now wills to remove and that he gives to both North and South this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offenses come, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to him? Fondly do we hope fervently do we pray–that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, “The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan-to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, a lasting, peace among ourselves and with all nations.

By Henry Cabot Lodge and Theodore Roosevelt, 1895. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2025.

Also See:

Assignation of President Abraham Lincoln

The Gettysburg Address (November 19, 1863 Speech at Gettysburg National Cemetery Dedication)

The Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment

John Wilkes Booth – Actor to Assassin

About the Author: The latter part of this article was written by Henry Cabot Lodge and Theodore Roosevelt and included in the book Hero Tales From American History, first published in 1895 by The Century Co, New York. However, the text as it appears here is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clarity and ease for the modern reader.