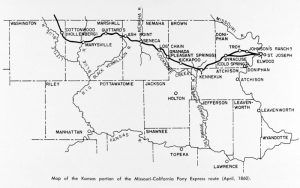

More than 25 stations were situated in Division One at various times in the states of Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska. Beginning in St. Joseph, Missouri, the trail crossed the Missouri River to Kansas. Six of the Division One stations are listed on the National Register of Historic Places today.

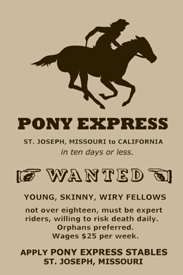

William H. Russell, William Bradford Waddell, and Alexander Majors were already in the freighting business with 4,000 men, 3,500 wagons, and 40,000 oxen in 1858. They held government contracts for delivering army supplies in the west, and Russell envisioned a similar contract for fast mail delivery. Their headquarters were in St. Joseph, Missouri.

St. Joseph Station Area – In St. Joseph, Missouri, several sites are associated with St. Joseph Home Station and the Pony Express National Historic Trail. These include:

Pony Express Stables – The stables, located at 914 Penn Street, face Patee Park in Saint Joseph, Missouri. In 1858, Ben Holladay constructed the original pine-clad building, the Pike’s Peak Stable, to serve his transportation business to Colorado. The original stable measured 60 x 120 feet and housed approximately 200 horses. Thirty years later, the St. Joseph Transfer Company remodeled the stables after they had been damaged by fire. The roof retained its original configuration and shingles during remodeling, but the walls were re-sided with brick. In 1950, the Goetz Foundation restored the building by using original roof timbers and bricks. Today, the building serves as the Pony Express Museum and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Pony Express Monument – The monument in Patee Park in Saint Joseph, which stands across from the Pony Express Museum, was erected in memory of the birth of the Pony Express. The dedication ceremony for the monument, which occurred on April 3, 1913, included Pony Express riders such as William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, “Cyclone” Thompson, and Charlie Cliff. The monument reads: This monument erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution and the city of St. Joseph marks where the first Pony Express Started on April 3, 1860.

Patee House – This hotel, built from 1856-1858 by John Patee, served as a general office for the Pony Express in 1860. The Patee House often lodged Pony Express riders and founders of the company, including William H. Russell and Alexander Majors. The Patee House is a four-story, brick, Italianate commercial-style building that is handsomely decorated with brackets, quoins, pilasters, and ornamental window hoods. The building still stands at the corner of Twelfth and Penn Streets, approximately two and one-half blocks east of the Pony Express stables. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Pony Express Statue – The Pony Express Memorial Statue stands in a park on the corner of Frederick Avenue and Ninth Street and resembles an actual Pony Express rider with his mount. Herman A. MacNeil designed the statue. Since its dedication on April 20, 1940, the life-size bronze statue, weighing 7,200 pounds, has stood near City Hall and the Saint Joseph Civic Center.

St. Joseph Ferry Site – Two steam ferries, the Bellemont Ferry and the Ellwood Ferry, transported travelers, including Pony Express riders, across the Missouri River from Missouri to Kansas. Reportedly, the boat docked at either Jules or Francis Streets in Saint Joseph. A monument located along the shoreline of the Missouri River in Hustan Wyeth Park, represents the original site of the ferry crossing. This monument reads: On this site, April 3, 1860, a ferry carrying a horse and rider crossed the Missouri River to start a 10-day journey of 1,966 miles to deliver mail to Sacramento, California. The race against time, elements, and a hostile land captured the spirit of Americans, helped hold California for the Union, and proved a central overland route was possible. Operators William Russell, Alexander Majors, and William Waddell went broke without a government mail contract, and the telegraph replaced the daring Pony Express riders after 19 months of operation.

Pony Express Saddle and Mochila Monument – This monument stands at the site where the first rider reportedly departed from Saint Joseph. It was dedicated on April 3, 1990, by the Western Trails Museum and Pony Express Trail Association during the 130th Pony Express Awareness Anniversary. It reads: On April 3, 1860, the eastern Pony Express mail arrived by train. The mail was brought here, which was the site of the United States Express Company. They were agents of the famous Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Company, which owned the Pony Express and had offices at 12th and Penn Streets in the Patee House. The mail was first put into the four cantinas (pockets) of the ‘mochila’ (mo-che-la). The mail consisted of a few newspapers, 49 letters, and nine telegrams printed on lightweight paper and wrapped in oiled skin for additional protection. The first Pony Express left here on April 3 at 7:15 p.m. and, after nearly 2,000 miles, arrived in San Francisco at 1:00 a.m. on April 14. That westbound trip took ten days, seven hours, and 45 minutes.

Elwood – Situated just across the Missouri River from St. Joseph is Elwood, Kansas. Pony Express riders, wagon trains, and thousands of westbound emigrants crossed the ferry into Kansas. The Elwood Free Press, on April 21, 1860, mentioned that this was the first station on the Pony Express.

There were two routes between Elwood and Cold Springs, one 20 miles long and the other 24. The latter went through Troy. It is not certain which route was used most. Elwood, first called Roseport, was established in 1856. In its heyday, scores of river steamboats unloaded passengers and freight at its wharves, and every 15 minutes, ferry boats crossed to its Missouri rival, St. Joseph. During the 1850s, thousands of emigrants outfitted here for Oregon and California. Late in 1859, Abraham Lincoln, seeking the Republican nomination, here first set foot in Kansas and spoke in the three-story Great Western Hotel. Elwood was the first Kansas station on the Pony Express between Missouri and California. Construction of the first railroad west of the Missouri River began here in 1859. On April 23, 1860, the first locomotive, “The Albany,” was ferried and pulled up the bank by hand. However, Elwood’s ambitions for greatness were thwarted when the Missouri River undermined the banks and washed away much of the old town. However, the town still exists today with a population of about 1200 people.’

Troy Station – Various sources indicate that this site was located within the town of Troy, at the head of Mosquito Creek, a tributary of the Missouri River. A monument in the northwest corner of the courthouse lawn notes the existence of the relay station. Some authors list the monument’s location as the possible site of the station, but, later research links the station with the Smith Hotel. Leonard Smith arrived in Troy in 1858 and purchased the Troy Hotel. Two years later, at the request of the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express, he constructed a barn large enough for five horses. The renamed Smith Hotel served as a relay station and was located at the present-day northeast corner of East Main and Myrtle Streets. There is a Pony Express marker at the site. The July 1936 Pony Express Courier reported that Troy served as the first relay station west of St. Joseph, a distance of about 15 miles. Stories associated with handing pastries to the passing rider Johnny Fry by the Dooley girls probably originated in the Troy area.

Cold Springs – Sometimes called Cold Springs Rock, this station was situated some 24 miles beyond St. Joseph at the Cold Spring Branch of Wolf River. Situated on the Pottawatomie Road at about S34-T3S-R20E, this was also a station for the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express.

In 1860, Sir Richard Burton, an English adventurer-writer, traveled across the American West beginning in St. Joseph, Missouri. As his stagecoach followed the overland route to Salt Lake City and then to San Francisco, he wrote about many of the stage stations that also served as Pony Express stops. Of Cold Springs, he said:

“Squalor and misery were imprinted upon the wretched log hut, which ignored the duster and broom. Myriads of flies disputed with us a dinner consisting of doughnuts, which were green and poisonous with saleratus, suspicious eggs in a massive greasy fritter, and intolerably fat rusty bacon. Fifty cents a head was a dear price to pay for flies, bad bread, and worse eggs and bacon.” — Sir Richard Burton August 7, 1860, 3:00 p.m.

Syracuse – Some sources list Cold Spring and Syracuse as the same station, while others suggest they were two different stations. One source lists its location at the head of the North Branch of Independence Creek. The Syracuse Hotel, owned by Walter Peck operated here from 1858-62 and William Vickery owned a store. The Vickery Family Cemetery is nearby.

Lewis Station – Also spelled “Louis,” L.C. Bishop and Paul Henderson named and mapped this place was on the Spring branch of the South Fork of Wolf River about 10 miles west of Cold Springs. It has been suggested that this station was possibly the same as the Cold Springs Ranch Station. The Lewis Station and Cold Springs Station were located the same distance between Troy and Kennekuk. However, another history resource placed the station on North Independence Creek. Several other sources give yet another location for this station. “Chain Pump” and “Valley Home/House” may have been other names for the site.

Kennekuk (Kinnekuk) Station – Experts on the Pony Express trail in this area have designated Kennekuk as the first home station west of St. Joseph. Most other sources agree on the name but, not the exact location of this station. Some have placed it approximately 44 miles along the trail. Other sources state that it stood approximately 39 miles from the beginning of the trail. The stage route from Atchison and the Fort Leavenworth-Fort Kearny Military Road combined with the trail near Kennekuk brought much traffic to the settlement in the early 1860s. At one time, the settlement was said to have boasted a dozen homes, a store, and a blacksmith shop. It was also the headquarters of the Kickapoo Indian agent, Major Royal Baldwin. Tom Perry and his wife ran the relay station and served meals to travelers passing through. In 1931, the Oregon Trail Memorial Association, a pioneering trail marking group that formed to mark the Oregon and other western trails, placed a Pony Express stone marker in Kennekuk for this station. A granite stone west of the marker and across the road indicates the site of the relay station. The stone memorial marker is 1.5 miles southeast of present-day Horton, Kansas. The Pony Express Courier of June 1939, reported that this was the fifth station out of St. Joseph.

Kickapoo/Goteschall Station – This relay station stood on Delaware Creek (also called Big Grasshopper or Plum Creek) about 12 miles west of Horton, Kansas, and was generally known as Kickapoo or Goteschall. Both the station and the stone Presbyterian mission, a nearby landmark, existed on the Kickapoo Indian Reservation. Noble Rising, a Kansas pioneer and surveyor, maintained the station with W. W. Letson. Unfortunately, both the relay station and mission are gone.

Log Chain Station – Several sources identify this place as both a Pony Express relay station and a stop on the Overland Stage route. Noble H. Rising, the station keeper, maintained a 24×40′ log house and 70-foot barn. His son, Don Rising, was among the first express riders employed by A.E. Lewis for his division. Log Chain Station stood on some maps near Locknane Creek, also called Locklane and Muddy Creek. It was named for the many wagons whose ox chains broke as they crossed the creek’s sandy bed. Over the years, Log Chain Station was altered and soon fell into ruins.

Pony Express Museum in Seneca, Kansas by Tom Hughes, RV Senior Moments

Seneca Station – Sources generally agree that Seneca Station’s location and identity as an early Pony Express home station, was also known as the Smith Hotel. John E. Smith and his wife Agnes managed the station operations at the hotel, located on the corner of present-day Fourth and Main Streets. Smith entered the hotel business in 1858, and his two-story white hotel also served as a restaurant, school, and residence. On July 1, 1860, it became a home station. In about 1900, the Smith Hotel was moved from its original site and relocated several blocks west. In 1972, the building was razed because of the lack of preservation funds. A marker designates the site of the original station in downtown Seneca.

Across the street from where the Smith Hotel once stood is a Pony Express Museum with a saloon, blacksmith shop, schoolroom, stables, a kitchen with many items from the Smith Hotel, and a typical parlor and bedroom of the hotel. The museum is located on 4th and Main Streets in Seneca, Kansas.

Ash Point/Laramie Creek Station – Located on the banks of Vermillion Creek, this station was also referred to as Frogtown and Hickory Point. The tiny settlement of Ash Point began at the junction of the Pony Express route and a branch of the California Road before 1860. “Uncle John” O’Laughlin, a storekeeper, managed the station operations and was said to have sold whiskey to stage passengers. Richard F. Burton, the noted English traveler, passed through Ash Point in November 1860, where the stage stopped for water at “Uncle John’s Grocery.” The town continued to serve as a stage stop in the 1860s but had faded away by the end of the 1870s. A stone-covered well, dug by John O’Laughlin, has been located at the station site.

Guittard (Gantard’s, Guttard) Station – Both a Pony Express station and a stage stop, it was owned by the George Guittard (Guttard) family. The GuittarGuittard family came to Kansas in 1857, establishing their ranch on Vermillion Creek as the earliest permanent settlement in that part of Marshall County, Kansas. George’s son, Xavier Guittard, managed the station, which alternated as a home or relay base at various times and a stage stop. A large, two-story house provided living quarters and a waiting room for stage passengers, and the roomy barn accommodated a blacksmith shop and stalls for some 24 horses. On August 8, 1860, Richard Burton saw the Pony Express rider arrive at Guittard’s Station, describing it:

“The house and kitchen were clean, the fences neat; the ham, eggs, hot rolls, and coffee were fresh and good. It was here for the first time that I saw the Pony Express rider in the course of his duties.“

In 1910, the house was dismantled, and the lumber went into a new dwelling on the same site, thereby destroying the site. Nevertheless, a door from the original house exists in a second-story room. A stone marker with a bronze plaque from the Oregon Trail Memorial Association, was placed near the site in June 1931.

Marysville Station – After crossing some prairie country, the next stop was Marysville, also known as Palmetto City. Situated about 112 miles west of St. Joseph, this place also served as a stage station for the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express. In 1859, Joseph H. Cottrell and Hank Williams contracted with Russell, Majors, and Waddell to build and lease a livery stable as a home station. The riders probably slept at the nearby Barrett Hotel, north of the livery stable. The north end of the stone stable served as a blacksmith shop, and stalls were located on the other side. The first westbound rider left St. Joseph, Missouri, early in the evening of April 3, 1860, arriving in Marysville the next morning. Historians differ on his identity, but local tradition says it was Johnny Fry. According to the travel writer Richard Burton, it was a town that thrived “by selling whiskey to ruffians of all descriptions.”

After serving as a livery stable, the building later housed a garage, produce station, and a cold storage locker plant. In 1876, a hip-style roof was added to the building after a fire destroyed the original board roof. On April 2, 1973, the stable joined the National Register of Historic Places. Today, the building serves as a museum, consisting of the original stable, the oldest building in Marshall County. An annex was added in 1991, which matches its in architectural style.

Cottonwood/Hollenberg Station – Located on Cottonwood Creek, a tributary of the Little Blue River, this place was not only a Pony Express stop but also a stage station and store for emigrant travelers. Situated five miles northeast of Hanover, Kansas, it is the only remaining Pony Express stop still standing in its original location and is probably the only unaltered Pony Express building on the route. Built on Cottonwood Creek in 1857 by Gerat H. Hollenberg, this station was also the largest stop along the Pony Express route in Kansas. Hollenberg’s six-room building initially served as a grocery store, tavern, and an unofficial post office, intending to capitalize on the many wagon trains passing his way on the Oregon-California Trail. Three years later, it became a Pony Express station and, later, a stagecoach station. In 1941, the Kansas State Legislature purchased the station and the surrounding acreage to preserve the site, which is managed by the Kansas State Historical Society today. It is listed as a National Historic Landmark.

Atchison Station – Some historical sources have determined that St. Joseph, Missouri, may not have served as the eastern terminus of the Pony Express throughout its operating period from April 3, 1860, to October 26, 1861. One such source suggests that as early as January 1860, the Pony Express may have changed its starting point from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Atchison, Kansas. Pony riders leaving Atchison intersected with the old Pony Express route at Kennekuk. However, it is more likely that Atchison served as the eastern terminus for the Pony Express after the 1861 Overland Mail Company contract was signed in March 1861. This contract stated that the eastern terminus could be either St. Joseph, Missouri, or Atchison, Kansas. Therefore, Atchison could have served as the terminus during the latter months of the existence of the Pony Express. Frank A. Root, who lived in Atchison in 1861 and was employed as assistant postmaster there, remembered that in the last six or seven weeks of the Pony Express, most, if not all of the Pony Express mail passed through the Atchison post office via the overland stage to and from Fort Kearny, Nebraska.

Lancaster Station – If Atchison was used as the eastern terminus, Lancaster, located before Kennekuk, served as the first station east of Atchison. This relay station was located ten miles from Atchison and eleven miles from the starting point of the original east-west Pony Express route. Lancaster was also known as a stage stop on the Holladay stage line.

Rock House Station – The Pony Express moved out of Kansas following the Blue River to Fort Kearny, Nebraska. This first relay station was located in Jefferson County as a stop for stagecoaches, Pony Express riders, and weary travelers. It was about three miles northeast of Steele City, where the Oketo cut-off merged with the main route. It has also been called Caldwell and Otoe.

Rock/Turkey Creek Station – Located near Fairbury, Nebraska, Rock Creek Station was an important road ranch on the Oregon Trail, first established in 1857 by S. C. Glenn. In the beginning, it was only a small cabin with a lean-to and barn situated on the west side of Rock Creek. In its earliest days, the lean-to was a primitive store, where hay, grain, and supplies could be bought, sold, or traded by the traffic along the Oregon Trail.

In 1859, David McCanles bought Rock Creek Station, built a log cabin, and dug a good well on the east side of Rock Creek. He erected a toll bridge across the creek, eliminating the crude rock ford. His usual fee ranged from 10 to 50 cents, depending on a person’s ability to pay. The following year, he rented the land on the east side of the creek to Russell, Majors, and Waddell for use as a swing station where Pony Express riders could quickly change their mounts. A small log structure served as the relay station. The hewn-log building had an outside-accessible attic and stone fireplace and measured 36 feet long, 16 feet wide, and 8 feet high at the eaves.

On July 12, 1861, it was here that the legendary gunfight between David McCanles and James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok took place. At that time, the 24-year-old Bill Hickok was working as a stock tender when he and Horace Wellman got into an altercation with David McCanles. When the smoke cleared, three men were dead. Both Hickok and Wellman were charged with murder, but, both were acquitted.

Alternative names and sites for the station include Turkey Creek, Pawnee, and possibly Elkhorn and the Lodi Post Office. Today, the site is part of the Rock Creek Station State Historical Park, located three miles northeast of Endicott, Nebraska. An Oregon Trail and Pony Express marker lies near the park entrance. The 350-acre park provides Pony Express exhibits, reconstructed buildings, pioneer graves, and trail ruts.

Virginia City – This site is located four miles north of Fairbury, in Jefferson County, Nebraska. Other names for the station include Grayson’s and Whiskey Run. A place called Lone Tree possibly served as an alternate station site, which was located one mile south of Virginia City.

More area history is situated about 1.25 miles west on country road 716. Here is the grave of George Winslow, who lost his life of cholera while traveling the Oregon-California Trail to the goldfields in 1949.

Big Sandy Station – This site is reportedly about three miles east of Alexandria in Jefferson County. Sources generally agree about its identity as a Pony Express station, with stagecoaches also stopping there. Dan Patterson owned and operated the site as a home station until 1860 when he sold it to Asa and John Latham. History also associates the Daniel Ranch, a post office, and the Ed Farrell Ranch with the Big Sandy Station.

Millersville/Thompson’s Station – This site is about two miles north of Hebron in Thayer County. George B. Thompson acted as the station keeper for Pony Express operations at this station, and the station was named after him. A monument erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1912 continues to stand near the site. After the Pony Express ended, the California-Oregon Trail continued to be traveled in this area. During August 1864, several Indian attacks took place along the Little Blue River between Deshler and Oak Grove. A series of roadside historical signs tell of the events in the area.

Kiowa Station – Located about seven miles northwest of Deshler, this site served as a stop for both the Pony Express and the Leavenworth & Pike’s Peak Express Company and Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express stagecoaches. Jim Douglas managed the station operations. Several settlers were killed in this vicinity during the 1864 Cheyenne and Lakota Sioux attacks along the Little Blue River. The site is situated in a farm field.

Between the old Kiowa Station and the Oak Grove Station are two sites where Indian attacks took place. About four miles west of the Kiowa Station, a marker designates the Emery Stagecoach Ambush site on the road’s south side. Here, a life-and-death race occurred as a passenger-filled stagecoach was chased through the area by a war party on August 10, 1864. About 1.5 miles to the southwest is the site of the old Bowie Ranch. A pioneer couple was slain in their home during the 1864 uprising. There are no remains of the ranch today.

Little Blue/Oak Grove Station – Located 1.5 miles southeast of Oak, Nebraska, is the Oak Grove Station, also known as the Little Blue Station and the Comstock Ranch. Al Holladay managed this station, which reportedly had a “Majors and Waddell” store next to it. Ranchers in the area included Roper, Emory, Eubank, and E. S. Comstock, whose land carried the name of Oak Grove Ranch.

On August 9, 1864, a suspiciously friendly party of some 20 Cheyenne warriors dropped in for a visit at the Oak Grove Station. While visiting casually with nervous ranch workers, the Cheyenne suddenly struck, killing two men and wounding two more. Eleven ranch workers fled into the ranch house, and another escaped into a grove of trees. The warriors abruptly rode off as an ox train approached. The next day, the survivors fled, and the warriors returned, setting fire to the original buildings. No original buildings remain today, but it is commemorated with a Pony Express monument.

As the trail continued along the Little Blue River to Deweese, Nebraska, this was another area that suffered Indian attacks in August 1864. Several homesteaders were killed, and five were taken captive. At the Eubank Homestead, located 1.5 miles northwest of Oak Grove, warriors destroyed the homestead and killed two children who were home alone. A short distance north of the ranch, three Eubank men and a teenage boy were slain while cutting hay, and a younger boy was taken captive. Another 1/2 mile to the northwest, the Eubank parents, their two babies, and a visiting teenage girl were taking a stroll along The Narrows section of the trail when they heard screaming from their homestead. The father was slain as he ran to the aid of his children. The women and babies hid in the brush but were captured, to be released months later.

Cheyenne on horses, Edward S. Curtis, 1910

Liberty Farm Station – This site is generally acknowledged to be located on the north bank of the Little Blue River about half a mile northeast of Deweese, in Clay County. James Lemmons and Charles Emory managed it. Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express stagecoaches also stopped at Liberty Farm. After the Pony Express went out of business, the station remained a stage stop with J.M. Comstock serving as station keeper. During the Indian uprising of 1864, it was burned to the ground.

Spring Ranch/Lone Tree Station – Located 4.2 miles west and 3 miles north of Deweese, this was a prosperous road ranch along the trail. Since the 1861 mail contract did not list Spring Ranch as a stopping point, the identification of Spring Ranch as a Pony Express station remains controversial. However, its location between two known distant stations, Liberty Farm and Thirty-Two Mile Creek would have made Spring Ranch a convenient place for riders to change horses. Several other sources identify this station as Lone Tree, a relay station, and a stage stop. During the Indian uprising of 1864, the owners rushed to safety in a nearby town, and the ranch and two other homesteads in the area were attacked and destroyed.

Thirty-Two Mile Creek Station – Located about six miles southeast of Hastings in Adams County, this site was a Pony Express relay station and a stage station for the Leavenworth and Pike’s Peak Express Company and the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express. George A. Comstock served as station-keeper of the long, one-story building, named after the distance between it and Fort Kearny. When English writer and traveler, Sir Richard Burton passed the station on August 9, 1860, he said:

“At 9 p.m., reaching ‘Thirty-two Mile Creek,’ we were pleasantly surprised to find an utter absence of the Irishry. The station master was the head of a neat-handed and thrifty family from Vermont; the rooms, such as they were, looked cozy and clean, and the chickens and peaches were plump and well “fixed.” Soldiers Fort Kearny loitered about in the adjoining store, and from them, we heard of past fights and rumors of future wars which were confirmed on the morrow.”

During the Indian uprising in August 1864, Comstock abandoned the station, and the warriors burned the station to the ground. Today, the National Register of Historic Places designates the station’s location as a historical archaeological site.

Sand Hill/Summit Station – This site is thought to have been located about 1.5 miles south of Kenesaw near Summit Springs. The nearby sandy wagon road gave the station its other name, Sand Hill. Other resources suggest it might have also been called Fairfield or Water Hole. Like the other stations in the area, it was destroyed in the Indian attacks of 1864.

Hook’s/Kearney/Valley Station – This site is thought to have been located 1.5 miles northeast of Lowell in Kearney County and for a time served as a relay station for the Pony Express. It has also been referred to as Dogtown, Valley City, Junction City, Hinshaw’s Ranch, and Omaha Junction. Whichever name is associated with this station, M. H. Hook managed the operations at the site. This station was the last one under the jurisdiction of St. Joseph-Fort KearnyDivision Superintendent E. A. Lewis.

Fort Kearny – Since Fort Kearny was a stage stop on the Leavenworth & Pike’s Peak Express Company and Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express lines, it is likely that Russell, Majors, and Waddell also used this site as a Pony Express station. However, some historians are unsure, as privately owned businesses were not granted space on U.S. military bases. However, Pony Express riders possibly stopped at Fort Kearny to service the mail needs of the military. The fort saw a lot of traffic from the military, and riders possibly made stops at the sod post office, built in 1848. Some resources suggest that Doby Town (Kearney City), about two miles west of the fort, is a more likely location for the station.

Kearney City (Dobytown) – Two miles west of Fort Kearny, the small commercial center of Kearney City was established in 1859. The town’s more common name, Dobytown, was derived from the resemblance of its 12-15 earthen buildings made of adobe. Dobytown developed in response to the thousands of soldiers, freighters, and travelers whose “needs” could not be met within the Fort. Gambling, liquor, and disreputable men and women were its principal attractions. However, in addition to its notorious functions, Dobytown also served as the major outfitting point west of the Missouri River, as the center of frontier transportation from 1860 to 1868, and a Pony Express station.

Compiled and edited Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2022.

Also See:

Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Company

Cheyenne War of 1864, Nebraska

Pony Express – Fastest Mail Across the West

Sources:

Kansas Heritage

Pony Express Historic Research Study

St. Joseph, Missouri