Fort Kearny, Nebraska.

The Grattan Fight marked the beginning of 3½ decades of intermittent warfare on the northern Plains. On a summer afternoon in 1854, a young lieutenant, belligerently seeking to arrest a Sioux Indian for a trivial offense, forced a fight. By sundown, all the troops but one were dead. An enraged American public, unaware of the actual circumstances, demanded action. The Sioux and other northern tribes, with whom relations rapidly deteriorated, made numerous raids along the Oregon-California Trail. The next year, General William S. Harney led a punitive expedition (1855-56) onto the Plains from Fort Kearny, Nebraska. The Indian Wars, a bitter, generation-long struggle, had begun.

During the years just preceding the Grattan Fight, despite the waves of settlers passing west over the trail, the northern Plains Indians had been relatively peaceful. In July and early August 1854, about 600 lodges of Brule, Miniconjou, and Oglala Sioux, as well as those of a few Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho, dotted the North Platte River Valley for several miles east of Fort Laramie, Wyoming.

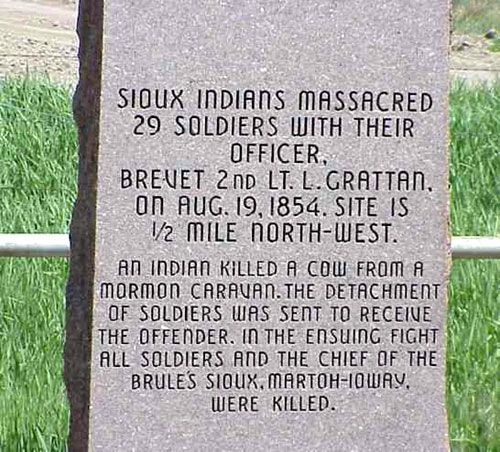

This large concentration of Indians, which could easily have overwhelmed the fort’s feeble garrison, was impatiently awaiting the delayed annuity issue to which they were entitled by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. On August 18, 1854, a cow ran into the village when a Mormon caravan passed Conquering Bear’s Brule camp about eight miles east of Fort Laramie. It was shot and killed by a visiting Miniconjou Indian named High Forehead.

This matter was reported at the fort by the Mormons and Brule Chief Conquering Bear to Fort Laramie’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Hugh B. Fleming. Though the chief offered to make amends, the Lieutenant rejected the overtures and decided to arrest High Forehead, an act in violation of existing treaties. The commander assigned the mission to John L. Grattan, a rash 24-year-old lieutenant fresh out of West Point, and gave him broad discretionary powers.

The next afternoon, Grattan, an interpreter named Lucien Auguste, and 29 infantrymen set out with a wagon and two small cannons. They stopped first at the Gratiot Houses fur trading post and then at James Bordeaux’s trading post, 300 yards from the Brule camp and eight miles southeast of Fort Laramie. Over Grattan’s protests, at both places, the interpreter, who had become intoxicated, abused, and threatened the loitering Indians.

High Forehead refused to give himself up. A series of conferences between Grattan and Conquering Bear and other chiefs culminated in front of High Forehead’s lodge, where Grattan finally moved his troops despite the warnings of the alarmed James Bordeaux. The chiefs made new offers to pay for the cow, pleaded with the unyielding Grattan to postpone action until the Indian agent arrived, and continued to urge the obstinate High Forehead to surrender. Conquering Bear explained that High Forehead was a guest in his village and was not subject to his authority. Aggravating matters was the arrival of some impetuous young Oglala warriors, who had hurried down from their village in defiance of Grattan’s orders. Distrusting Auguste’s translation of what was being said and seeking to avoid a clash, Conquering Bear tried but failed to obtain the translation services of Bordeaux. As the situation became tenser, the Brule women and children fled from the camp toward the river.

At some point, a few shots were fired, and an Indian fell, but the chiefs cautioned the warriors not to reciprocate. Convinced of the need for an even greater show of force, Grattan ordered his men to fire a volley. Conquering Bear slumped to the ground, mortally wounded. Arrows flew. Once Grattan fell, his command panicked and fought a running battle back along the Oregon-California Trail. Finally, the mounted Indians, forcing the foot soldiers onto level ground, overwhelmed them. All died except for one mortally wounded man who managed to return to Fort Laramie.

The Indian chiefs, feeling that the Great White Father would recognize the soldiers’ partial fault and forgive the Indians for the battle, did not attack Fort Laramie.

Within a few days, they did, however, pillage Bordeaux’s nearby trading post and helped themselves to both annuity goods and company property, the Gratiot Houses, as a substitute for their annuities.

Afterward, the Brule departed from the North Platte River Valley. The Cheyenne and Arapaho waited only for the distribution of treaty goods before moving away. In the meantime, life at Fort Laramie settled into the familiar routine, but the old security was gone.

The U.S. press called the event the “Grattan Massacre,” ignoring the fact that the U.S. soldiers had instigated the event by shooting Conquering Bear and that Grattan was violating treaty conditions by his intervention. When news of the fight reached the War Department, officials started planning retaliation to punish the Sioux. Before long, General William S. Harney was sent to Fort Kearny, Nebraska, where he was put in command of elements of his own 2nd US Dragoons. They set out on August 24, 1855, to find and exact retribution on the Sioux.

On September 3, 1855, they engaged the Sioux in the Battle of Ash Hollow, also known as the Battle of Bluewater Creek. Taking place near present-day Lewellen, Nebraska, several of the Brule Sioux warriors were killed. Some historians believe the Grattan massacre triggered the next several decades of intermittent warfare on the Great Plains.

The site, privately owned and used for ranch operations, is marked by a stone monument on the north side of the road. Extensive modern terrain alterations for irrigation purposes make it impossible to identify the exact positions of the participants in the fight. The site of the cairn, where the enlisted men were first buried, is about 200 yards west of the probable site of the Bordeaux trading post, marked by ground debris. They were later moved to a group burial at the Nebraska National Cemetery at Fort McPherson, Nebraska. Grattan’s body is interred at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The likely site of Gratiot Houses, also debris-covered, is located about ten yards from the river, about a quarter-mile east of the headgates of the Gratiot Irrigation Ditch. The site is located in Goshen County, between an unimproved road and the North Platte River, about three miles west of Lingle.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2025.

Also See:

Indian War Campaigns and Battles

Primary Source: National Park Service