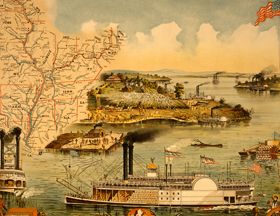

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in the United States and all of North America, at more than 2,300 miles long. It is the fourth-longest and the tenth-most powerful river in the world. Originating at Lake Itasca, Minnesota, it flows slowly southwards until it ends about 95 miles below New Orleans, Louisiana, where it begins to flow into the Gulf of Mexico. Along with its major tributary, the Missouri River, the river drains all or parts of 31 U.S. states. It stretches from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the Appalachian Mountains in the east to the Canadian border on the north and includes most of the Great Plains.

No river has played a greater part in the development and expansion of America than the Mississippi. Since the first person viewed this mighty stream, it has been a vital factor in the physical and economic growth of the United States.

It has stood in the path of discoverers, challenging their ingenuity to cross it. It has fired the imaginations of explorers, luring them on to seek out its mysteries. And always, it has stood in the minds of practical men as the key to westward expansion, an economic prize to be sought and held at all costs. As such, it has been fought over on the battlefield and used as a pawn in diplomatic exchanges.

From tiny Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it twists and turns through the land of the Chippewa, 2,348 miles south through the heart of the United States. It sweeps past Minneapolis and St. Paul, growing larger as tributaries add their flows. It is joined by the Missouri River north of St. Louis and receives the waters of the Ohio River at Cairo, Illinois. Here it becomes the Lower Mississippi, a river giant unequaled among American waters. Flowing south, it touches romantic river towns — Memphis, Greenville, Vicksburg, Natchez, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans. Almost 1,000 river miles south of Cairo, Illinois, it pours its torrent into the Gulf of Mexico.

The area of the Mississippi Valley was first settled by Native American tribes, including the Cheyenne, Sioux, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, Fox, Kickapoo, Tamaroa, Moingwena, Quapaw, and Chickasaw.

Christopher Columbus may have been the first European to view the Mississippi River. An “Admiral’s Map” in the Royal Library at Madrid, Spain, said to have been engraved in 1507, shows the mouth of the river, then called “The River of Palms.” Though this may have been the Mississippi River, it has never been confirmed.

In May 1541, Hernando De Soto was the first recorded European to view the Mississippi at a point near or just below present-day Memphis, Tennessee. He called it the Río del Espíritu Santo (“River of the Holy Spirit.”) After he died in 1542, his followers continued the explorations. The expedition’s historian, Garciliaso de la Vega, described the Mississippi as a flood of great severity and prolonged duration. The flooded areas were described as extending for 20 leagues on each riverside.

One hundred and twenty years later, Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet began exploring the river, traveling from its upper reaches to a point near present-day Arkansas City, Arkansas. Marquette traveled with a Sioux Indian named Ne Tongo and proposed calling it the River of the Immaculate Conception.

In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, and Henri de Tonti descended the greater portion of its length to its mouth. and claimed the entire Mississippi River Valley for France, calling it the Colbert River after Jean-Baptiste Colbert.

In March 1699, Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville rediscovered the mouth of the Mississippi following the death of La Salle. At a point near Old River, Louisiana, he received a letter from an Indian chief previously left there by LaSalle. A short time later, the French built the small fort of La Balise there to control passage.

Within a few years, French traders had settled along the Mississippi River and had penetrated the territory of the Natchez Indians. In 1705, the first cargo was floated down the river from the Indian country around the Wabash River in the present-day states of Indiana and Ohio. This was a load of 15,000 bear and deer hides brought downstream and out through Bayou Manchac, just below Baton Rouge, and Amite River, then through Lake Maurepas and Lake Pontchartrain to Biloxi, with a final destination in France. This route is not now open, Bayou Manchac having been closed with the construction of the Mississippi River levee system.

Fort Rosalie, the first permanent white settlement on the Mississippi River, now called Natchez, was built by the French in 1716. Bienville founded New Orleans in 1718, and four years later, this city was made the capital of the region known as Louisiana. The rapid growth of New Orleans was due principally to its position near the mouth of the river. Navigation grew and developed with the settlement of the Lower Mississippi Valley.

Following Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War, the Mississippi River became the border between the British and Spanish Empires. The Treaty of Paris in 1763. signed by Great Britain, France, and Spain, with Portugal giving Great Britain rights to all land east of the Mississippi and Spain rights to land west of the river. The Treaty of Paris also stated: “The navigation of the river Mississippi, from its source to the ocean, shall forever remain free and open to the subjects of Great Britain and the citizens of the United States.”

Mississippi River near Cairo, Illinois.

Decades later, France reacquired “Louisiana” from Spain in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800. The United States bought the territory from France in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. In 1815, the U.S. defeated Britain at the Battle of New Orleans, part of the War of 1812, securing American control of the river.

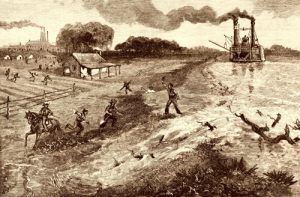

The Indians’ canoes soon proved inadequate for the settlers’ needs. The flatboats and rafts that succeeded them were one-way craft only. Loaded at an upstream point, they floated downriver, unloading their cargoes, dismantling them, and selling them for lumber. Built for one trip only, they were cheap and often poorly constructed but carried large quantities of merchandise at a time when transportation was vital to the growing valley.

The keelboat was the first queen of the river trade. A two-way traveler, it was long and narrow with graceful lines, built to survive many trips. A keelboat could carry as much as 80 tons of freight. Floated downriver, it was “Cordelled” up the stream. This called for a crew of tough and hardy men, for cordelling was a process by which a crew on the bank towed the keelboat along against the current.

The invention of the steamboat in the early 19th century brought about a revolution in river commerce. The first steamboat to travel the Mississippi was the New Orleans. Built in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1811 at the cost of $40,000, she was a side-wheeler 116 feet long and weighed 371 tons.

On her maiden voyage, the New Orleans was caught in a series of tremors known as the “New Madrid Earthquake,” probably the worst non-volcanic earth shock in American history. Nevertheless, she continued downriver on a nightmarish trip to become the first steamboat to travel the Mississippi, arriving in New Orleans on January 12, 1812. She was then placed in service between New Orleans and Natchez. Two years later, she hit a stump and sank.

In December 1814, Captain Henry M. Shreve brought a cargo of supplies for General Andrew Jackson’s army from Pittsburgh to New Orleans in his side-wheeler, the Enterprise. He climaxed his trip by running the British batteries below New Orleans to deliver military supplies to Fort St. Philip.

Although steamboats were in service between New Orleans and Natchez, they had not yet traveled far upriver. Shreve met this challenge with his steamboat called the George Washington, built in 1816 at Wheeling, West Virginia. It had a flat, shallow hull and a high-pressure engine. In 1817, the George Washington made the round trip from Louisville, Kentucky, to New Orleans and returned in 41 days.

The golden era of the paddle-wheeler had begun. In 1814, only 21 steamboats arrived in New Orleans; in 1819, there were 191; and in 1833, more than 1,200 steamboat cargoes were unloaded.

Some steamboats operated on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, mostly between New Orleans and Louisville, Kentucky. In 1817, there were 14; in 1819, 31. However, the appearance of the steamboat on the Mississippi River above the mouth of the Ohio River was delayed for several years: In August of 1817, the Zebulon M. Pike made the trip up the river to St. Louis, Missouri. Three years later, the Western Engineer made a trip from St. Louis up the Missouri River and later a part of the way up the Mississippi above St. Louis. In April 1823, the Virginia left St. Louis bound for scattered posts up the Mississippi. Twenty days and 683 miles later, the Virginia docked at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers, the first steamboat to make this trip.

By 1830, the steamboat age had come to the upper Mississippi, and by 1840, there was heavy river commerce between St. Louis and the head of navigation at St. Anthony’s Falls, near present-day St. Paul, Minnesota.

By 1830, the steamboat age had come to the upper Mississippi, and by 1840, there was heavy river commerce between St. Louis and the head of navigation at St. Anthony’s Falls, near present-day St. Paul, Minnesota.

The steamboat could haul freight and had comfortable accommodations for passengers. Even more important, it could travel upstream almost as easily as it traveled downstream. In the period preceding the Civil War, its decks carried cotton and other produce to market; it brought back the staples and fineries available only from outside the region, brought visitors from afar, and furnished transportation to other sections of the country.

Though steamboat travel was hazardous and irregular in the early years, it furnished faster, more dependable, and more useful transportation than other forms of travel. Nevertheless, it left much to be desired during its early development period.

Before the invention of the steamboat, a trip from Louisville to New Orleans often required four months. In 1820, the trip was made by steamboat in 20 days. By 1838, the same trip was being made in 6 days.

Missouri Steamboat.

These boats were by no means small by Mississippi River standards. The Lee was 300 ft long and weighed 1,467 tons, while the Natchez was 301.5 ft long and weighed 1,547 tons. They were both longer than the Sprague, the largest paddle-wheel towboat ever built, and one had greater tonnage.

The packet boat brought a phenomenal increase in traffic. In 1834, there were 230 packets; by 1849, there were about 1,000, approximating a total of 250,000 tons. The packet continued to be the principal means of transportation in the Mississippi River Valley until the latter part of the nineteenth century when commerce began to be diverted to the expanding railroads.

In 1820, Congress began addressing the navigational needs of the nation’s interior by authorizing a reconnaissance of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. Fieldwork, begun in 1821, extended from Louisville, Kentucky, to the mouth of the Ohio River and from St. Louis, Missouri, to New Orleans on the Mississippi River. That same year, two Engineer officers, Brigadier General Simon Barnard and Major Joseph G. Totten, were sent to investigate the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers thoroughly. Their report submitted the following year contained observations on the physical characteristics of the rivers and gave considerable attention to the formation and removal of snags. Legislation was enacted in 1824, directing the removal of these snags and other obstructions from the channels of the rivers.

Congress first improved the mouth of the Mississippi River for seagoing navigation in 1837, with an appropriation for an accurate survey of the passes and bars at the river’s mouth. Captain A. Talcott, Corps of Engineers, conducted this survey and finished it in 1838. He recommended a plan for deepening the bars by dredging, but a lack of necessary funds prevented substantial progress on this channel.

By 1850, the growing river commerce and increasing destruction caused by floods created a demand for Federal participation in navigation improvements and flood protection.

In 1850, the Secretary of War, conforming to an Act of Congress, directed Charles Ellet Jr., an engineer, to make surveys and reports on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers to prepare adequate plans for flood prevention and navigation improvement. His report was complete, and it considerably influenced later improvements.

That same year, Congress appropriated $50,000 to prepare a topographic and hydrographic survey of the Mississippi River delta and investigate the most practicable plans for flood control and navigation improvements at the mouth of the river. But, it was not until 1861 that Captain A. A. Humphreys and Henry L. Abbott of the Corps of Engineers completed their field investigations and submitted their report. While their findings dealt primarily with flood control, they also considered the navigation problem.

Meanwhile, keeping the river’s mouth open to oceangoing traffic was one of the nation’s growing concerns, and Congress appropriated $75,000 in 1852 to improve the channel at the mouth of the river.

Control of the Mississippi River was a strategic objective of both sides during the Civil War, and several battles were fought on and near the waterway. In 1862, Union forces coming down the river successfully cleared Confederate defenses at Island Number 10 in present-day New Madrid, Missouri, and in Memphis, Tennessee. In the meantime, Naval forces coming upriver from the Gulf of Mexico captured New Orleans, Louisiana. The last Confederate stronghold on the mighty river was on the bluffs overlooking the river at Vicksburg, Mississippi. It, too, fell during the Union’s Vicksburg Campaign of December 1862 to July 1863, which completed control of the lower Mississippi River. The Union victory ending the Siege of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, was pivotal to the Union’s final victory of the Civil War.

It was not until 1867 that dredging operations were resumed at the mouth of the Mississippi River, but still, the vexing problem of keeping the river’s mouth open to oceangoing traffic was not solved. No significant progress had been made by 1873 when Captain James B. Eads, a famous construction engineer, advocated a system of parallel jetties. He offered to open the mouth of the river by making a jetty-guaranteed channel 28 feet deep between Southwest Pass and the Gulf at his own risk. If he succeeded, his fee would be $10,000,000.

After much debate, in 1875, Eads was directed to begin his work in the South rather than Southwest Pass. He faced a difficult task complicated by yellow fever and unfavorable financial arrangements; however, he pushed the project to completion. On July 8, 1879, a 30-foot channel was officially declared to exist at the mouth of the Mississippi.

The importance of the Mississippi River to the Nation had, by now, become firmly established. Congress had shown an increasing interest in flood control and navigation problems on the Mississippi, and legislation designed to improve this mighty stream for the use of the Nation was rapidly taking form. In 1874, Congress authorized certain surveys of transportation routes to the seaboard. Five years later, the Board of Engineer officers concluded that a complete levee system would only aid commerce during periods of high water.

That same year, in June 1879, the Mississippi River Commission was created by an Act of Congress as an executive body reporting to the Secretary of War. The Commission comprised seven men nominated by the President of the United States and confirmed by the Senate.

Since the enactment of the Flood Control Act of May 15, 1928, the Commission has served as an advisory and consulting – rather than an executive body responsible to the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army. The general duties of the Commission include the recommendation of policy and work programs, the study of and reporting upon the necessity for modifications or additions to the flood control and navigation project, recommendation upon any matters authorized by law, making inspection trips, and holding public hearings.

Barges on the Mississippi River, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The Commission’s work is directed by its President, who acts as its executive officer, and carried out by U.S. Army Engineer Districts at St. Louis, Memphis, Vicksburg, and New Orleans.

During World War II, Mississippi River transportation assumed an even more important role than ever before. The principal commerce on the lower Mississippi River consisted of the upstream movement of gasoline, oil, sulfur, and other products and materials vital to the war effort. In addition, nearly 4,000 Army and Navy craft and other vessels for use in the war moved from inland shipyards down the Mississippi to the sea.

Without question, the Nation’s principal river, the Mississippi, is the main stem of a network of inland navigable waterways maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. This giant waterways system, of some 12,350 miles, includes the Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, Arkansas, and Tennessee Rivers, among others. It extends into the agricultural midwest and the industrial east, making Memphis, Vicksburg, and New Orleans close neighbors of Pittsburgh, Kansas City, and Chicago.

The Mississippi River continues to be a powerful form of transportation today as large towboats haul barges filled with steel, ores, grain, sand and gravel, petroleum products, chemicals, and more.

The Great River Road.

Today, the history of the Mighty Mississippi is commemorated at National and State parks, museums, interpretive centers, and numerous events. The Great River Road National Scenic Byway runs through ten scenic states — Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

This historic byway of the Mississippi River is one of North America’s oldest, longest, and most unique scenic byways. It provides nearly 3,000 miles of the Mississippi River Valley’s great history, the blending of cultures, charming river towns, lush forests, magnificent bluffs, and more. The Great River Road follows the Mississippi River from its humble headwaters in Minnesota’s north woods to the Gulf of Mexico.

The Great River Road dates back to 1938 when the governors of the ten river states developed the concept of a transcontinental Great River Parkway along the Mississippi River. Wishing to conserve precious resources, it was decided that rather than building a new continuous road, the existing network of rural roads and then-fledgling highways that meandered and crisscrossed the river would become the Great River Road. The green Pilot’s Wheel road sign that marked the route of the new byway decades ago still heralds the byway today.

Along the way, there are eight National Park Service sites, including the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area in Mississippi, that are dedicated to protecting and interpreting the river itself. The other six National Park Service sites along the river are (listed from north to south):

- Effigy Mounds National Monument in Harpers Ferry, Iowa

- Jefferson National Expansion Memorial (aka The Arch) in St. Louis, Missouri (Note: In February 2018, President Donald Trump signed legislation renaming the Memorial “Gateway Arch National Park”)

- Arkansas Post National Memorial in Gillett, Arkansas

- Vicksburg National Military Park in Vicksburg, Mississippi

- Natchez National Historical Park in Natchez, Mississippi

- New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park in New Orleans, Louisiana

- Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve in New Orleans, Louisiana

Numerous state, county, and city parks and museums also commemorate the great river’s history. Just a few of these include the Delta Cultural Center in Helena, Arkansas; the Black Hawk State Historic Site in Rock Island, Illinois; the National Great River Museum in East Alton, Illinois; Fort de Chartres State Historic Site in Prairie du Rocher, Illinois; Old Fort Madison in Ft. Madison, Iowa; Wickliffe Mounds State Historic Site in Wickliffe, Kentucky; Poverty Point State Historic Site in Pioneer, Lousiana; the Mary Gibbs Mississippi Headwaters Center at Itasca State Park in Minnesota; Historic Fort Snelling in Minneapolis, Minnesota; the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Mississippi; Mark Twain Boyhood Home & Museum in Hannibal, Missouri; the Great River Road Interpretive Center in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri; the Mississippi River Museum at Mud Island in Memphis, Tennessee; the Stonefield State Historic Site in Cassville, Wisconsin; the Fort Crawford Museum in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin; and dozens more.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2024.

See our Great River Road Photo Gallery HERE

Also See:

A Sketch of the Early “Far West”

Primary Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers