Powhatan Wars (1610-1646)

Pequot War (1636-1637)

King Philip’s War (1675-1676)

King William’s War (1688–1697)

French and Indian War (1689-1763)

Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713)

Dummer’s War (1722–1725)

King George’s War (1744–1748)

Father Le Loutre’s War (1749–1755)

French and Indian War (1754–1763)

Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763-1768)

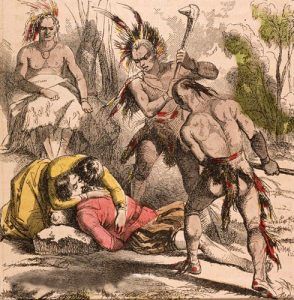

Like other relations between European settlers and Native Americans throughout American History, tensions between the indigenous people of the land and the new Americans began almost from the beginning. From the settling of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 to the opening of the 18th century, several conflicts would occur for various reasons, including the new settlers’ demands for food and land, cultural differences, and the need of both cultures to defend themselves from the other. Two years after the colonists settled in Jamestown, the first war began between the Powhatan and the new settlers. It would be followed by numerous others, including the Pequot War, King Philip’s War, King William’s War, and dozens of other conflicts.

In 1607, when the first English settlement was established at Jamestown, Virginia, relations were mixed between the new settlers and the Powhatan tribe, upon whose hunting grounds they had settled. Though there was no initial violence, the settlers built a fort to protect themselves from Indian attacks. In June, their leader, Captain Newport, left for England to get more supplies for the new settlement. Those who remained, however, were not prepared. Not long after Newport left, the settlers began to die from various diseases, most probably caused by drinking bad water. They were also running short of supplies and were hungry. That first winter, while Captain John Smith was out exploring, he was captured and taken to Werowocomoco where the Powhatan lived. There, he and the Powhatan Chief, Wahunsunacock, conversed and came to an understanding. Smith was released in the spring of 1608, and the Powhatan then began to send gifts of food to help the English. Were it not for their help, the settlement would most likely have failed, as all the English would have died from disease or starvation.

However, the new settlers began demanding, feeling they could trade tools and Christianity for food. They failed to understand that the Powhatan way of life barely provided for themselves, much less another community. By late 1609, after a drought during the summer, the settlers added pressure on the Indians for more food supplies. As a result, Chief Powhatan, tired of the constant English demands for food, officially told his people not to help them. The relationship deteriorated between the two peoples resulted in the Powhatan Wars, which would continue off and on until 1646.

More Wars With The Indians

The period from 1660 to 1675, a time of readjustment in the affairs of the New England colonies, was characterized by widespread excitement and deep concern on the part of the colonies everywhere. The territories, from Maine to the frontier of New York and the towns of Long Island, all felt the strain of impending change in their political status.

Adding to the distress of the early colonists of the New World was the ever-present danger of Indian attacks. The stretches of unoccupied land between the colonies were the hunting grounds of the Narragansett of eastern Connecticut and western Rhode Island, the Pequot of Connecticut, the Wampanoag of Plymouth and its neighborhood, the Pennacook of New Hampshire, and the Abnaki tribes of Maine.

Plague and starvation had so far weakened the coast Indians before the first colonists’ arrival that the new settlements had been but little disturbed. However, as the firstcomers pushed into the interior, founding new plantations, felling trees, and clearing the soil, trappers and traders invaded the Indian hunting grounds, carrying firearms and liquor, and the Indian menace became serious.

To meet the Indian peril, all the colonies made provisions for supplying arms and drilling the citizens in militia companies. But, in equipment, discipline, and morale, the fighting force of New England was imperfect. The troops had no uniforms; there was a very inadequate commissariat, and alarms, whether by a beacon, drumbeat, or discharge of guns, were slow and unreliable. Weapons were crude, and the method of handling them was exceedingly awkward and cumbersome. The pike was abandoned early, and the matchlock soon gave way to the flintlock — both heavy and unwieldy instruments of war — and carbines and pistols were also used. Though expensive because of horse and outfit, cavalry or mounted infantry was introduced whenever possible. In 1675, Plymouth had 14 companies of infantry and cavalry; Massachusetts had six regiments, including the Ancient and Honorable Artillery; and Maine and New Hampshire had one each. Connecticut had four train bands in 1662 and nine in 1668, a troop of dragoneers, and horses, but no regiments until the next century. For coast defense, there were forts, very inadequately supplied with ordnance, of which that on Castle Island in Boston harbor was the most conspicuous, and, for the frontier, there were garrison houses and stockades.

Though Massachusetts had twice put herself in readiness to repel attempts at coercion from England, and though both Connecticut and New Haven seemed, on several occasions, in danger from the Dutch, particularly after the recapture of New Amsterdam in 1673, New England’s chief danger was always from the Indian s. Both French and Dutch were believed to be instrumental in inciting Indian warfare, one along the southwestern border, the other at various points in the north, notably in New Hampshire and Maine. But, except for occasional Indian forays, house-burnings, and scalpings in the more remote districts, there were only two serious wars in the seventeenth century – that against the Pequot in 1637 and the great war of King Philip in 1675-1676.

The Pequot War, which Connecticut carried on with a few men from Massachusetts and several Mohegan allies, ended in the complete overthrow of the Pequot nation and the extermination of nearly all its fighting force. It began in June 1637, with the successful attack by Captain John Mason on the Pequot fort near Groton, and was brought to an end by the Battle of Fairfield Swamp on July 13th, where the surviving Pequot made their last stand. Sassacus, the Pequot chieftain, was murdered by the Mohawk, among whom he had sought refuge; and during the year that followed, wandering members of the tribe, whenever found, were slain by their enemies, the Mohegan and Narragansett. An entire Indian people were wiped out of existence, an achievement difficult to justify on any ground save the extreme necessity of either slaying or being slain. The relentless pursuit of the scattered and dispirited remnants of these tribes admits little defense.

The overthrow of the Pequot opened to settlement of the region from Saybrook to Mystic. It led to a treaty in 1638 with the Mohegan and Narragansett, according to which harmony was to prevail and peace was to reign. But, the outcome of this impracticable treaty was a five years struggle between the Mohegan chieftain, Uncas, actively allied with the colony of Connecticut, and Miantonomo, sachem of the Narragansett, which involved Connecticut in a tortuous and often dishonorable policy of attempting to divide the Indians to rule them – a policy which led to many embarrassing negotiations and bloody conflicts and ended in the murder of Miantonomo in 1643, by the Mohegan, at the instigation of the commissioners of the United Colonies.

This alliance between Uncas and the colony lasted for more than 40 years. It placed upon Connecticut the burden of supporting a treacherous and grasping Indian chief; it created a great deal of confusion in land titles in the eastern part of the colony because of indiscriminate Indian grants; it started the famous Mohegan controversy, which agitated the colony and England also, and was not finally settled until 1773, 130 years later; and it was, in part at least, a cause of King Philip’s War, because of the colony’s support of the Mohegan against their traditional enemies, the Narragansett and Niantic.

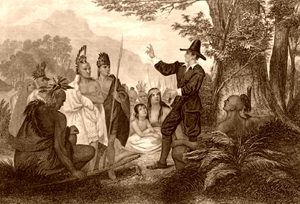

The presence of the Indians in and near the colonies rendered frequent dealings with them a matter of necessity. The English settlers generally purchased their lands from the Indians, paying for such goods or implements or trinkets. In so doing, they acquired, as they supposed, a clear title of ownership, though there can be no doubt that what the Indian thought he sold was not the actual soil but only the right to occupy the land in common with himself. As the years wore on, the problems of reservations, trade, and the sale of firearms and liquor engaged the attention of the authorities and led to the passage of many laws. The conversion of the Indians to Christianity became the object of many pious efforts. In Massachusetts and Plymouth, it resulted in communities of “Praying Indians,” estimated in 1675 at about 4,000 individuals. In contact with the white man, the Indians tended to deteriorate. He frequented the settlements often to the annoyance of the men and the dread of the women and children; he got into debt, was incurably slothful and idle, and developed an uncontrollable desire to drink and steal. Where the Indians were not a menace, they were a nuisance, and the colonies passed many laws concerning the Indians designed to meet one condition and the other.

But, the real danger to New England came not from those Indians who occupied reservations and hung around the settlements but from those who, with savage spirits unbroken, were slowly being driven from their hunting grounds and nurtured an implacable hatred against the aggressive and relentless pioneers. The New Englanders numbered some 80,000 individuals, with an adult and fighting population of perhaps 16,000, while the number of the Indians altogether may have reached as high as 12,000, with the Narragansett, the strongest of all, mustering 4,000. The final struggle for possession of the main part of central and southern New England territory came in 1675, in what is known as King Philip’s War.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

Also See:

Native Americans – First Owners of America

About This Article: Though part of this article was written by Kathy Alexander of Legends of America, the bottom portion was excerpted from The Fathers of New England: A Chronicle Of The Puritan Commonwealths, which Charles M. Andrews, a professor of history at Bryn Mawr College, edited. Yale University Press published it in 1918.