By Charles M. Andrews, 1918

King Philip’s War, also called the First Indian War and Metacom’s War, was an armed conflict in 1675-78 between American Indians and New England colonists and their Indian allies.

Scarcely had the fears aroused by the arrival of a Dutch fleet at New York and the capture of that city been allayed by the Peace of Treaty of Westminster, signed by the Netherlands and England in 1674, when rumors of Indian unrest began to spread through the American settlements. The dread of Indian outbreaks began to arouse new apprehensions in the hearts of the people.

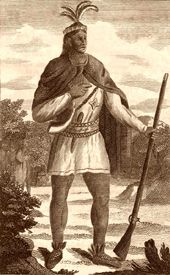

Before this, no Indian chieftain had proved himself a born leader of his people. Neither Sessaquem, Sassacus, Pumham, Uncas, nor Miantonomo had been able to quiet tribal jealousies and draw others to follow him. But, now appeared a sachem who was the equal of any in hatred of the white man and the superior of all in generalship, gifted both with the power of appeal to the younger Indians and with the finesse required to rouse other chieftains to a war of vengeance. Philip, or Metacom, was the second son of old Massasoit, the longtime friend of the English, and, upon the death of his elder brother Alexander in 1662, became the head of the Wampanoag, with his seat at Mount Hope, a promontory extending into Narragansett Bay on the Massachusetts and Rhode Island border.

Believing that his people had been wronged by the English, particularly those of Plymouth colony, and foreseeing that he and his people were to be driven step-by-step westward into narrower and more restricted quarters, he began to plot a great campaign of extermination. On June 24, 1675, a group of Indians fell on the town of Swansea in present-day Massachusetts, on the eastern side of Narragansett Bay, slew nine inhabitants, and wounded seven others.

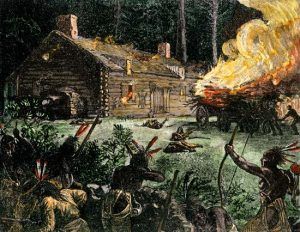

Though assistance was sent from Massachusetts and Plymouth, the burning and massacring continued, extending to Rehoboth, Taunton, and towns northward. The settlements were isolated before the troops could reach them, their inhabitants were slain, cabins were burned, and prisoners were carried into captivity. The Rhode Islanders fled to the islands; elsewhere, settlers gathered in garrisoned forts, blockhouses, and new forts hastily erected.

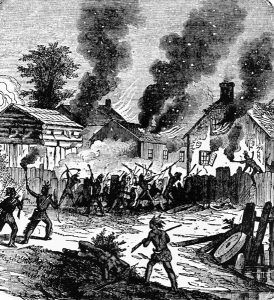

Though the authorities of Connecticut and Massachusetts sent agents among the Nipmuck hoping to prevent their alliance with Philip, the effort failed. By August, the tribes on the upper Connecticut River had joined the movement and began a determined and systematic destruction of the settlements in central New England. The famous massacre and burning of Deerfield, Massachusetts, took place on September 12, with the surviving inhabitants fleeing to Hatfield, leaving their town in ruins. Hatfield, Northfield, Springfield, and Westfield were attacked in turn, and though the defense was sometimes successful, the defenders were ambushed and killed more often. So widespread was the uprising that during the autumn, desultory warfare was carried on as far north as Falmouth, Brunswick, and Casco Bay, in Maine, where members of the Saco and Androscoggin tribes slew at least fifty Englishmen.

The Narragansett, the bravest of all the southern New England Indians, whose chief was Canonchet, son of the murdered Miantonomo, had taken no part in the war. But, as rumor spread that they had welcomed Philip and listened to his appeals and were probably planning to join in the murderous fray, war was declared against them on November 2, 1675. A force of a thousand men and horses from Plymouth and Massachusetts was drawn up on Dedham plain under the command of General Josiah Winslow and Captain Benjamin Church. On December 19th, the greater part of this force, aided by troops from Connecticut, fell on the Narragansett in their swamp fort, south of the present town of Kingston, and after a fierce and bloody fight, completely routed them, though at a heavy loss. The tribe was driven from its own territory, and Canonchet fled to the Connecticut River, where he established a rallying point for new forays.

His followers then allied themselves with the Wampanoag and Nipmuc and began a new series of massacres. In February and March 1676, they fell upon Lancaster, Massachusetts, where they carried off Mary Rowlandson, who has left us a narrative of her captivity; upon Medfield, where 50 houses were burned; and upon Weymouth and Marlborough, which were raided and in part destroyed. Repeated assaults in other quarters kept the western frontier of Massachusetts in a frightful condition of terror; settlers were ambushed and scalped, others were tortured, and many were carried into captivity. Even the Pennacook of southern New Hampshire were roused to action, though their share in the war was small. Here, a hundred warriors sacked a village; Indians skulked along trails and, on the outskirts of towns, cut off individuals and groups of individuals, shooting, scalping, and burning them. No one was safe. Again the commissioners of the United Colonies met in council and ordered a more vigorous prosecution of the campaign. More troops were levied, and garrison posts fortified, but the first results were disastrous. Captain Pierce of Scituate was ambushed at Blackstone’s River near Rehoboth, Massachusetts, and his command was completely wiped out. Sudbury, Massachusetts, was destroyed in April, and a relieving force escaped only with heavy loss.

But, the strength of the Indians was waning. Canonchet ran to earth near the Pawtuxet River, was captured and sentenced to death, and his execution was entrusted to Oneko, the son of Uncas. His head was cut off and carried to Hartford, Connecticut, and his body was committed to the flames. The loss of Canonchet was a bitter blow to Philip, who now saw his allies falling away and himself deserted by all but a few faithful followers. The campaign — at last well in hand and directed by that prince of Indian fighters, Benjamin Church, now commissioned a colonel by General Josiah Winslow — was approaching an end. Using friendly Indians as scouts, Colonel Church gradually located and captured stray bodies of Indians and brought them as captives to Plymouth. Finally, coming on the trail of Philip himself, he first intercepted his followers and then, relentlessly pursuing the fleeing chieftain from one point to another, tracked him to his lair at his old stronghold, Mount Hope, Rhode Island. There, the great chief who had terrorized New England for nearly a year was slain by one of his own race. The soldiers seized his ornaments and treasure, and his crown, gorget, and two belts, all of gold and silver of Indian make, were sent as a present to King Charles II. With the death of Philip on August 12, 1676, the whole movement collapsed, and the remaining hostile Indians, dispersed and in flight, with their leaders gone and starvation threatening, sought refuge among the northern tribes. Thus, the last effort to check the English advance in southern and central New England ended. From then on, the Indians in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut lingered for a century and a half, a steadily dwindling remnant, wards of the governments and occupants of reservations, until they ceased to exist as a separate people.

The havoc wrought by the war was a great blow to the prosperity of New England. Probably more than 600 white settlers had been slain or captured, and hundreds of houses and a score of villages had been burnt or pillaged; crops had been destroyed, cattle were driven off, and agriculture, in many quarters, brought to a complete standstill. In 1676, there was little leisure to sow and less to reap. Provisions became increasingly scarce; none could be had near at hand, for none of the colonies had a surplus, and attempts to obtain them from a distance proved unavailing. Staples for trade with the West Indies decreased; the fur trade was curtailed, and fishing was hampered for want of men. To add to the confusion, a plague vexed the colonies. It seemed to all as if the hand of God lay heavily upon New England, and days of humiliation and prayer were appointed to assuage the wrath of the Almighty. A Massachusetts act of November 1675 ascribed the war to the judgment of God upon the colony for its sins, among which were included an excess of apparel, the wearing of long hair, and the rudeness of worship, all marks of abandoning religious beliefs. The Puritan fear of divine displeasure adds a relieving note to the general despondency. It must have stiffened the determination of the orthodox leaders to resist to the utmost all attempts to liberalize the colony’s life or to alter its character as a religious state patterned after the divine plan. King Philip’s War probably strengthened the position of the conservative element in Massachusetts.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

About This Article: Edited by Charles M. Andrews, a professor of history at Bryn Mawr College, this article was excerpted from The Fathers of New England: A Chronicle Of The Puritan Commonwealths, which the Yale University Press published in 1918. Though the article, as it appears here, is contextually the same, it is not verbatim, as it has been edited.

Also See: