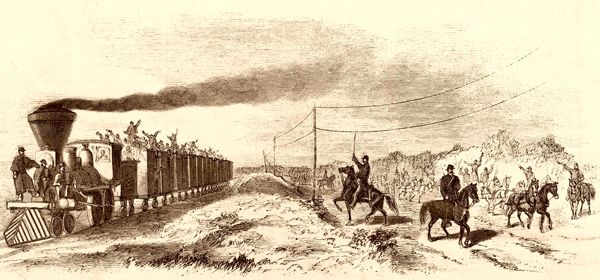

National Troops Under General Joseph E. Johnston advancing on the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1862.

A “border state” during the Civil War, Kentucky was of key importance to the Union, so much so that President Abraham Lincoln declared, “I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.”

Kentucky Civil War Battles

Barbourville (September 19, 1861)

Camp Wildcat (October 21, 1861)

Ivy Mountain (November 8-9, 1861)

Rowlett’s Station (December 17, 1861)

Middle Creek (January 10, 1862)

Mill Springs (January 19, 1862)

Richmond (August 29-30, 1862)

Munfordville (September 14-17, 1862)

Perryville (October 8, 1862)

Paducah (March 25, 1864)

Cynthiana (June 11-12, 1864)

The Civil War in Kentucky

Pitting families, friends, and neighbors against each other, the people of Kentucky had sympathy for both sides of the North and South’s critical issues during the Civil War. Its location meant its citizens had contact with people from across the U.S., especially those traveling along the Ohio River. There were 225,000 slaves in the state, but there were also many people who actively supported the Underground Railroad.

During the years leading up to the Civil War, Kentucky had produced men like Henry Clay, the “Great Compromiser,” and John Crittenden, author of the Crittenden Compromise. Along with many others, both of them worked to keep their state and the country together, but that goal seemed to be slipping away as the 1860s began.

The Civil War divided a few states as deeply as it did Kentucky. Citing the state’s history of supporting compromise and nationalism, some residents wanted to remain with the Union. Others favored the Confederacy, concentrating on the state’s ties to the South through culture–most importantly, by slave-owning–and through the family. In an attempt to keep these divisions from widening further, the state legislature declared in May 1861, a month after the firing on Fort Sumter, South Carolina, that it had decided to “occupy a position of strict neutrality.”

However, both the Union and the Confederacy were trying to convince residents to support their side, for each understood how that the state was crucial to their success. Control of Kentucky would assist in defense of other crucial territory and provide access to key transportation routes. It had the third-largest white population of all the slave-holding states, so it contained a large number of potential soldiers, and it produced wheat and livestock, supplies both sides would need.

Unionists gradually came to dominate the state. Congressional elections in May and August 1861 both ended with significant victories for men who favored the North. Many Kentuckians who had remained uncertain which side to support began to sympathize with the Union in September 1861, when Confederate General Leonidas Polk took control of Columbus, a railroad junction that sat at the foot of a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River. Polk’s attempt to take the state for the Confederacy created sympathy for the North, and the Kentucky legislature petitioned the Union for assistance, and thereafter, became solidly under Union control. Union General Ulysses S. Grant soon occupied two other towns in Kentucky.

Even as Kentucky tilted towards the Union, it remained far from united. Each side recruited troops from the state, and these enlistments caused splits that ran through families and neighborhoods. All but one of Mary Todd Lincoln’s seven brothers and half-brothers, for example, fought against the Union that her husband was trying to preserve.

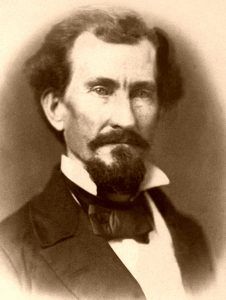

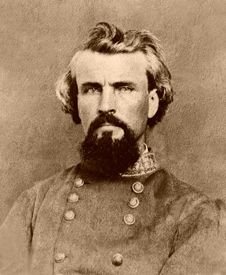

Kentucky was the site of fierce battles, such as Mill Springs and Perryville. It was host to such military leaders as Union General Ulysses S. Grant, who first encountered serious Confederate gunfire coming from Columbus, Kentucky, and Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest proved to be a scourge to the Union Army in such places as Sacramento and Paducah, where he conducted guerrilla warfare against Union forces.

Operations in Eastern Kentucky (September-December 1861)

When the Kentucky Legislature had taken steps that amounted to an adherence to the Confederates, General Sidney Johnston immediately crossed into Kentucky and dispatched General Buckner with a division toward Louisville. General Zollicoffer entered the State and advanced as far as Somerset. Licking Station served as a temporary camp for the constant stream of recruits and refugees from the interior of the state who were on their way to Virginia or intended to join the Confederate Army. In the meantime, Union General William “Bull” Nelson was instructed to collect all men available with the objective of dispersing the Confederate recruiting camp at Prestonburg, thus freeing Eastern Kentucky from the threat of a Confederate presence. In late October, he gathered a force of about half a dozen regiments at Olympian Springs and began his march toward Prestonsburg.

The Battle of Barbourville is commemorated in a small park in Barbourville, Kentucky, Kathy Weiser-Alexander, September 2012.

Battle of Barbourville (September 19, 1861) – Occurring in Knox County, this skirmish took place in Barbourville, Kentucky. Union sympathizers had trained recruits at Camp Andrew Johnson, in Barbourville, throughout the summer of 1861. Confederate Brigadier General Felix Zollicoffer entered Kentucky in mid-September intending to relieve pressure on General Albert Sidney Johnston and his troops by conducting raids and generally constituting a threat to Union forces and sympathizers in the area. On September 18, 1861, he dispatched a force of about 800 men under Colonel Joel A. Battle’s command to disrupt the training activities at Camp Andrew Johnson. At daylight on the 19th, the force entered Barbourville and found the recruits gone; they had been sent to Camp Dick Robinson. A small home guard force commanded by Captain Isaac J. Black met the Rebels, and a sharp skirmish ensued. After dispersing the home guard, the Confederates destroyed the training camp and seized the arms found there. This was, for all practical purposes, the first encounter of the war in Kentucky. The Confederates were making their might known in the state, countering the early Union presence. The Confederate victory resulted in estimated casualties of 15 Union and 5 Confederate.

Camp Wildcat (October 21, 1861) – Also called the Battle of Wildcat Mountain, this skirmish occurred in Laurel County as part of the Kentucky Confederate Offensive. The battle took place when Brigadier General Felix Zollicoffer’s men occupied Cumberland Gap and took a position at Cumberland Ford to counter the Unionist activity in the area. Brigadier General George H. Thomas sent a detachment under Colonel T.T. Garrard to secure the ford on the Rockcastle River, establish a camp at Wildcat Mountain, and obstruct the Wilderness Road passing through the area. Colonel Garrard informed General Thomas that if he did not receive reinforcements, he would have to retreat because he was outnumbered seven to one. Thomas sent Brigadier General A. Schoepf with a brigade of men to Colonel Garrard, bringing the total force to about 7,000. On the morning of October 21, 1861, soon after General Schoepf arrived, some of his men moved forward and ran into Rebel forces, commencing a fight.

The Federals repelled the Confederate attacks, in part due to fortifications, both man-made and natural. The Confederates withdrew during the night and continued their retreat to Cumberland Ford, which they reached on October 26th. A Union victory was welcomed, countering the Confederate victory at Barbourville. The battle resulted in estimated casualties of 25 Union and 53 Confederate.

Ivy Mountain (November 8-9, 1861) – Also called the Battle of Ivy Creek or Ivy Narrows, this conflict took place in Floyd County. While recruiting in southeast Kentucky, Rebels under Colonel John S. Williams ran short of ammunition at Prestonsburg and fell back to Pikeville to replenish their supply. Union Brigadier General William Nelson sent out a detachment from near Louisa under Colonel Joshua Sill while he started out from Prestonsburg with a larger force in an attempt to “turn or cut the Rebels off.” Confederate Colonel Williams prepared for evacuation, hoping for time to reach Virginia, and sent out a cavalry force to meet General Nelson about eight miles from Pikeville. The Rebel cavalry escaped, and Nelson continued on his way. Williams then met Nelson at a point northeast of Pikeville between Ivy Mountain and Ivy Creek. Waiting by a narrow bend in the road, the Rebels surprised the Yankees by firing upon their constricted ranks. A fight ensued, but neither side gained the bulge. As the shooting ebbed, Williams’ men felled trees across the road and burned bridges to slow Nelson’s pursuing force. Night approached, and rain began which, along with the obstructions, convinced Nelson’s men to go into camp. In the meantime, Williams retreated into Virginia, stopping in Abingdon on November 9th. Colonel Sill’s force arrived too late to be of use, but he did skirmish with Williams’s retreating force remnants before he occupied Pikeville on November 9th. The bedraggled Confederate force retreated back into Virginia for relief. The Union forces consolidated their power in the eastern Kentucky mountains. Though the battle was indecisive, it was considered a Union victory because the Confederates withdrew. Casualties included 30 Union and 263 Confederate.

Rowlett’s Station (December 17, 1861) – Also called the Battle of Woodsonville or the Battle of Green River, this skirmish occurred in Hart County. After Union Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell took command of the Department of the Ohio in early November, he attempted to consolidate control by organizing and sending troops into the field. He ordered Brigadier General Alexander McCook, commanding the 2nd Division, to Nolin, Kentucky. In the meantime, the Confederates had established a defensive line along the Green River near Munfordville. McCook launched a movement towards the enemy lines on December 10, 1862, which the Rebels countered by partially destroying the Louisville & Nashville Railroad bridge over the Green River. As a result, the Union sent two companies of the 32nd Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment across the river to prevent a surprise attack and began constructing a pontoon bridge for the passage of trains and artillery. When the bridge was completed on December 17th, four more of the 32nd Indiana companies crossed the river. The combined force advanced to a hill south of Woodsonville where, in the afternoon, they spotted enemy troops in the woods fronting them. Two companies advanced toward the enemy, which fell back until Confederate cavalry attacked. A general engagement ensued as eight Yankee companies fought a much larger Confederate force. Fearing that the enemy might roll up his right flank, Colonel August Willich, commanding the regiment, ordered a withdrawal to a stronger position in the rear. Knowing of McCook’s approach, the Rebels also withdrew from the field. Although the battle results were indecisive, Union troops did occupy the area and ensured the movement of their men and supplies on the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. The indecisive battle resulted in an estimated 40 Union casualties and 91 Confederate.

Offensive in Eastern Kentucky (January 1862)

Though Confederate Brigadier General Felix K. Zollicoffer’s main responsibility was to guard Cumberland Gap, he advanced west into Kentucky to strengthen control in the area in November 1861. He fortified the area, especially on both sides of the Cumberland River. In the meantime, Union Brigadier General George Thomas received orders to drive the Confederates across the Cumberland River and break up Major General George B. Crittenden’s army. The two battles of the campaign — Mill Springs and Middle Creek, broke the main Confederate defensive line anchored in eastern Kentucky. Confederate fortunes in the state did not rise until summer when General Braxton Bragg and Major General Kirby Smith launched their Kentucky Campaign, culminating in the Battle of Perryville and Bragg’s subsequent retreat. Mill Springs was the larger of the two Union Kentucky victories in January 1862. With these victories, the Federals carried the war into Middle Tennessee in February.

Middle Creek (January 10, 1862) – This skirmish took place in Floyd County as part of the Offensive in Eastern Kentucky. More than a month after Confederate Colonel John S. Williams left Kentucky, following the fight at Ivy Mountain, Brigadier General Humphrey Marshall led another force into southeast Kentucky to continue recruiting activities.

From his headquarters in Paintsville, on the Big Sandy River, northwest of Prestonsburg, Marshall recruited volunteers and had a force of more than 2,000 men by early January, but could only partially equip them. Union Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell directed Colonel James Garfield to force Marshall to retreat into Virginia. Leaving Louisa, Garfield took command of the 18th Brigade and began his march south on Paintsville. He compelled the Confederates to abandon Paintsville and retreat to the vicinity of Prestonsburg. Colonel Garfield slowly headed south, but swampy areas and numerous streams slowed his movements, and he arrived in the vicinity of Marshall on January 9, 1862.

Heading out at 4:00 am on January 10th, Garfield marched a mile south to the mouth of Middle Creek, fought off some Rebel cavalry, and turned west to attack Marshall. Marshall had put his men in the line of battle west and south of the creek near its forks. Garfield attacked shortly after noon, and the fighting continued for most of the afternoon until Union reinforcements arrived in time to dissuade the Confederates from assailing the Federal left. Instead, the Rebels retired south and were ordered back to Virginia on January 24th. Garfield’s force moved to Prestonsburg after the fight and then retired to Paintsville. Union forces had halted the Confederates’ 1861 offensive in Kentucky, and Middle Creek demonstrated that their strength had not diminished. This victory, along with that of the Battle of Mill Springs a little more than a week later, cemented Union control of eastern Kentucky until Confederate General Braxton Bragg launched his offensive in the summer and fall. Following these two January victories in Kentucky, the Federals carried the war into Tennessee in February. The Union victory resulted in estimated casualties of 27 Union and 65 Confederate.

Mill Springs (January 19, 1862) – Also called the Battle of Logan’s Cross-Roads and the Battle of Fishing Creek, this conflict occurred in Pulaski and Wayne Counties of south-central Tennessee. See full article HERE.

Confederate Heartland Offensive (June-October 1862)

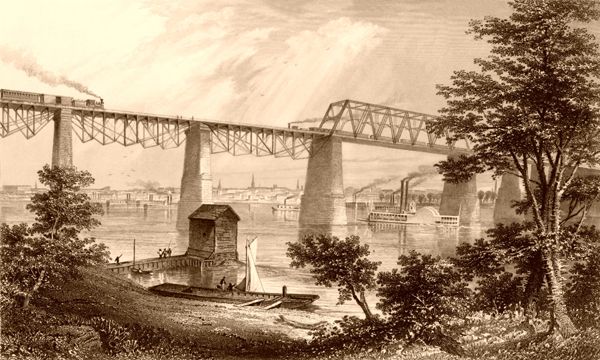

Like many other places during the Civil War, many of the battles in Kentucky were fought over the control of railroads. Louisville & Nashville Railroad by A.C. Warren,1872.

Also called the Kentucky Campaign, this series of maneuvers and battles took place in East Tennessee and Kentucky in 1862. From June through October, Confederate forces under the commands of General Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith launched a series of movements to outflank the Union Army of the Ohio and draw Kentucky’s border state into the Confederate States of America. Though the Confederates gained some early successes, their progress was stopped decisively at the Battle of Perryville, leaving Kentucky in Union hands for the rest of the war.

Richmond (August 29-30, 1862) – This battle took place in Madison County as part of the Confederate Heartland Offensive. In Major General Kirby Smith’s 1862 Confederate offensive into Kentucky, Brigadier General Patrick R. Cleburne led the advance with Colonel John S. Scott’s cavalry out in front.

The Rebel cavalry, while moving north from Big Hill on the road to Richmond, Kentucky, on August 29th, encountered Union troopers and began skirmishing. After Noon, Union artillery and infantry joined the fray, forcing the Confederate cavalry to retreat to Big Hill. At that time, Brigadier General Mahlon D. Manson, who commanded Union forces in the area, ordered a brigade to march to Rogersville toward the Rebels.

Fighting for the day stopped after pursuing Union forces briefly skirmished with Cleburne’s men in the late afternoon. That night, Manson informed his superior, Major General William Nelson, of his situation, and he ordered another brigade to be ready to march in support when required. Kirby Smith ordered Cleburne to attack in the morning and promised to hurry reinforcements (Churchill’s division). Cleburne started early, marching north, passed through Kinston, dispersed Union skirmishers, and approached Manson’s battle line near Zion Church. As the day progressed, additional troops joined both sides. Following an artillery duel, the battle began, and after a concerted Rebel attack on the Union right, the Yankees gave way. Retreating into Rogersville, the Yankees made another futile stand at their old bivouac. By now, Smith and Nelson had arrived and taken command of their respective armies. Nelson rallied some troops in the cemetery outside Richmond, but they were routed. Nelson and some men escaped, but the Rebels captured approximately 4,000 Yankees. The way north was open. The Confederate victory resulted in estimated casualties of 4,900 Union and 750 Confederate.

Munfordville (September 14-17, 1862) – Also called the Battle of Green River Bridge, this battle took place in Hart County. In the 1862 Confederate offensive into Kentucky, General Braxton Bragg’s army left Chattanooga, Tennessee, in late August. Followed by Major General Don Carlos Buell’s Union Army, Bragg approached Munfordville, a station on the Louisville & Nashville Railroad and the railroad bridge’s location crossing Green River, in mid-September. Colonel John T. Wilder commanded the Union garrison at Munfordville, which consisted of three regiments with extensive fortifications. Wilder refused Brigadier General James R. Chalmers’s demand to surrender on the 14th. Union forces repulsed Chalmers’s attacks on the 14th, forcing the Rebels to conduct siege operations on the 15th and 16th. Late on the 16th, realizing that Buell’s forces were near and not wanting to kill or injure innocent civilians, the Confederates communicated still another demand for surrender. Wilder entered enemy lines under a flag of truce. Confederate Major General Simon B. Buckner escorted him to view all the Rebel troops and convince him of the futility of resisting. Impressed, Wilder surrendered. The formal ceremony occurred the next day, on the 17th. With the railroad and the bridge, Munfordville was an important transportation center, and the Confederate control affected the movement of Union supplies and men. The Confederate victory resulted in an estimated 4,148 Union casualties and 714 Confederate.

Perryville (October 8, 1862) – This battle took place in Boyle County as part of the Confederate Heartland Offensive. In the fall of 1862, Confederate General Braxton Bragg and his troops had reached Louisville and Cincinnati’s outskirts, but he was forced to retreat and regroup. On October 7th, the Federal army of Major General Don Carlos Buell, numbering nearly 55,000, converged on the small crossroads town of Perryville, Kentucky, in three columns. Union forces first skirmished with Rebel cavalry on the Springfield Pike before the fighting became more general, on Peters Hill, as the gray-clad infantry arrived. At dawn, the next day, fighting began again around Peters Hill as a Union division advanced up the pike, halting just before the Confederate line. The fighting then stopped for a time. After Noon, a Confederate division struck the Union left flank and forced it to fall back. When more Confederate divisions joined the fray, the Union line made a stubborn stand, counterattacked, but finally fell back with some troops routed. Buell did not know of the happenings on the field, or he would have sent forward some reserves. Even so, the Union troops on the left flank, reinforced by two brigades, stabilized their line, and the Rebel attack sputtered to a halt. Later, a Rebel brigade assaulted the Union division on the Springfield Pike but was repulsed and fell back into Perryville. The Yankees pursued, and skirmishing occurred in the streets in the evening before dark. Union reinforcements were threatening the Rebel left flank by now. Bragg, short of men and supplies, withdrew during the night, and, after pausing at Harrodsburg, continued the Confederate retrograde by way of Cumberland Gap into East Tennessee. The Confederate offensive was over, and the Union controlled Kentucky. The Union victory resulted in estimated casualties of 4,211 Union and 3,196 Confederate.

Forrest’s Expedition into West Tennessee and Kentucky (March-April 1864)

In March 1864, Confederate Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest set out from Columbus, Mississippi, with a force of fewer than 3,000 men on a multipurpose expedition to recruit and re-outfit his troops and disperse the Federals from West Tennessee and Kentucky. The campaign consisted of two battles, one in Paducah, Kentucky, and the other at Fort Pillow, Tennessee.

Paducah (March 25, 1864) – This battle took place in McCracken County as part of Forrest’s Expedition into West Tennessee and Kentucky. In March 1864, Confederate Major General Nathan B. Forrest set out from Columbus, Mississippi, with fewer than 3,000 men on a multipurpose expedition to recruit, reoutfit, and disperse Union troops from the area of West Tennessee and Kentucky. Forrest arrived in Paducah on March 25th and quickly occupied the town. The Union garrison of 650 men under Colonel Stephen G. Hicks’ command retired to Fort Anderson, in the town’s west end. Hicks had support from two gunboats on the Ohio River and refused to surrender while shelling the area with his artillery. Most of Forrest’s command destroyed unwanted supplies, loaded what they wanted, and rounded up horses and mules. A small segment of Forrest’s command assaulted Fort Anderson and was repulsed, suffering heavy casualties.

Soon afterward, Forrest’s men withdrew. In reporting the town’s raid, many newspapers stated that Forrest had not found more than a hundred fine horses hidden during the raid. As a result, one of Forrest’s subordinate officers led a force back into Paducah in mid-April and seized the infamous horses. Although this was a Confederate victory, other than the destruction of supplies and animals’ capture, no lasting results occurred. However, it did warn the Federals that Forrest, or someone like him, could strike anywhere at any time. The Confederate victory resulted in an estimated 90 Union casualties and 50 Confederate.

Morgan’s Raid into Kentucky (June 1863) – Morgan’s Raid was a highly publicized incursion by Confederate cavalry into the Northern states of Indiana and Ohio. The raid took place from June 11–July 26, 1863, and is named for the Confederates commander, Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan. For 46 days as they rode over 1,000 miles, Morgan’s Confederates covered a region from Tennessee to northern Ohio. The raid coincided with the Vicksburg Campaign and the Gettysburg Campaign, although it was not directly related.

Cynthiana (June 11-12, 1864) – Also called the Battle of Kellar’s Bridge, this conflict occurred in Harrison County, Kentucky. Confederate Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan, a year after Morgan’s Raid into Kentucky, approached Cynthiana with 1,200 men, on June 11, 1864, at dawn. Colonel Conrad Garis, with the 168th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry and some home guard troops, about 300 men altogether, constituted the Union forces at Cynthiana. General Morgan divided his men into three columns, surrounded the town, and launched an attack at the covered bridge, driving the Union forces back towards the depot and north along the railroad. The Rebels set fire to the town, destroying many buildings and some of the Union troops as the fighting flared in Cynthiana, another Union force of about 750 men of the 171st Ohio National Guard under the command of Brigadier General Edward Hobson, arrived by train about a mile north of Cynthiana at Kellar’s Bridge. Morgan trapped this new Union force in a meander of the Licking River. After some fighting, Morgan forced Hobson to surrender. Altogether, Morgan had about 1,300 Union prisoners of war camping with him overnight in line of battle. Union Brigadier General Stephen Gano Burbridge, with 2,400 men, a combined force of Ohio, Kentucky, and Michigan mounted infantry and cavalry, attacked Morgan at dawn on June 12th. The Union forces drove the Rebels back, causing them to flee into town, where many were captured or killed. Confederate General John Morgan escaped. Cynthiana demonstrated that Union numbers and mobility were starting to take their toll, and the Confederate cavalry and partisans could no longer raid with impunity. The Union victory resulted in an estimated 1,092 Union casualties and 1,000 Confederate.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated January 2021.

Also See:

Western Theater of the Civil War

Eastern Theater of the Civil War

Civil War Trans-Mississippi & Pacific Coast Theaters

Lower Seaboard Theater & Gulf Approach of the Civil War

The American Civil War (main page)