The term “Underground Railroad” had no meaning to the generations that preceded the coming of the railroads and engines in the 1820s. Though the origin of the term “Underground Railroad” has not been determined, it refers to the effort of enslaved African Americans to gain their freedom by escaping bondage. By the 1820s, both those who aided freedom seekers and those who were outraged by the loss of their human property began to refer to escaped slaves as part of an “Underground Railroad.”

The very existence of slavery, the “peculiar institution,” as referred to by Thomas Jefferson, undermined that great call for equality in Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. The Underground Railroad — from the first decision to run away, through the actions of African American-organized Vigilance committees, to the liberating actions of John Brown — were all reminders of African American initiative and the notion of slavery as the single great immorality of that era. It allowed Americans of all kinds to play a role in resisting slavery.

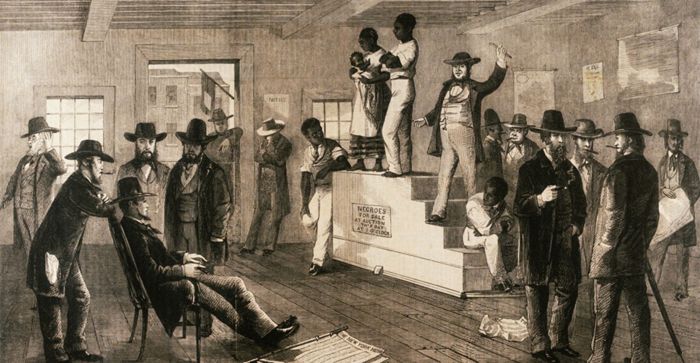

In the 18th century, slavery existed in all parts of the American colonies, though to distinct degrees in different locations. African Americans held in the northern area were more likely to be household servants, and slave owners were likely to possess only one or two slaves. However, enslaved Africans propelled the economy in the agricultural South, and owning large numbers of African Americans was seen as a symbol of high wealth and class.

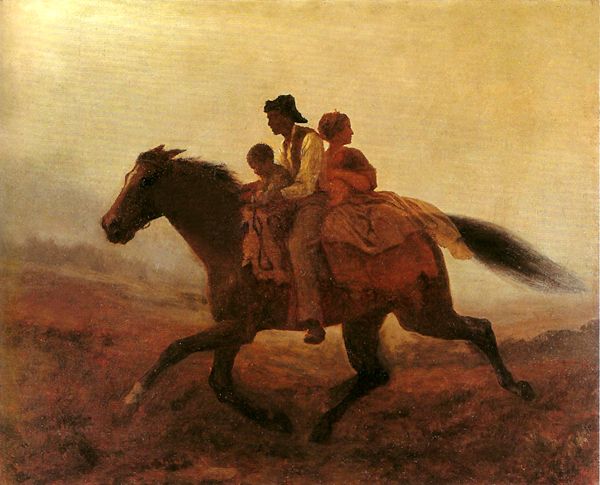

Wherever slavery existed, there were efforts to escape to isolated communities in remote or rugged terrain on the edge of settled areas. Their acts of self-emancipation made them “fugitives” according to the laws of the times. While most freedom seekers began their journey unaided and many completed their self-emancipation without assistance, each decade in which slavery was legal in the United States saw an increase in active efforts to assist escape.

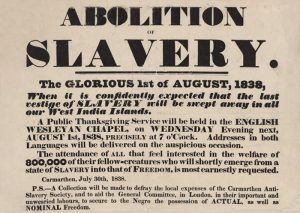

One measure of the Missouri Compromise of 1850 — the fugitive slave law — was thought by many to violate the principles of justice, as it provided no safeguard for the claimed fugitive against perjury and fraud. Every case that occurred under it — every surrender of a claimed fugitive — did more than the abolitionists had ever done to convert Northern people, to some part at least, to abolitionist beliefs. In a Senate debate on the compromise measures, Senator William Seward had made a casual allusion to “a higher law than the constitution,” and the phrase was caught up. To obstruct, resist, and frustrate, the execution of the statute came to be looked upon by many people as a duty dictated by the “higher law” of moral right. Legislatures were moved to enact obstructive ‘personal liberty laws, and “quiet” citizens were moved to riotous acts.

Active undertakings to encourage and assist the escape of slaves from the Southern states began, and a remarkable organization of helping hands was formed, taking the name of the “Underground Railroad” to hide and pass the freed slaves to the safe shelter of Canadian law. The slaveholders lost thousands of their servants for everyone that the law restored to their hands.

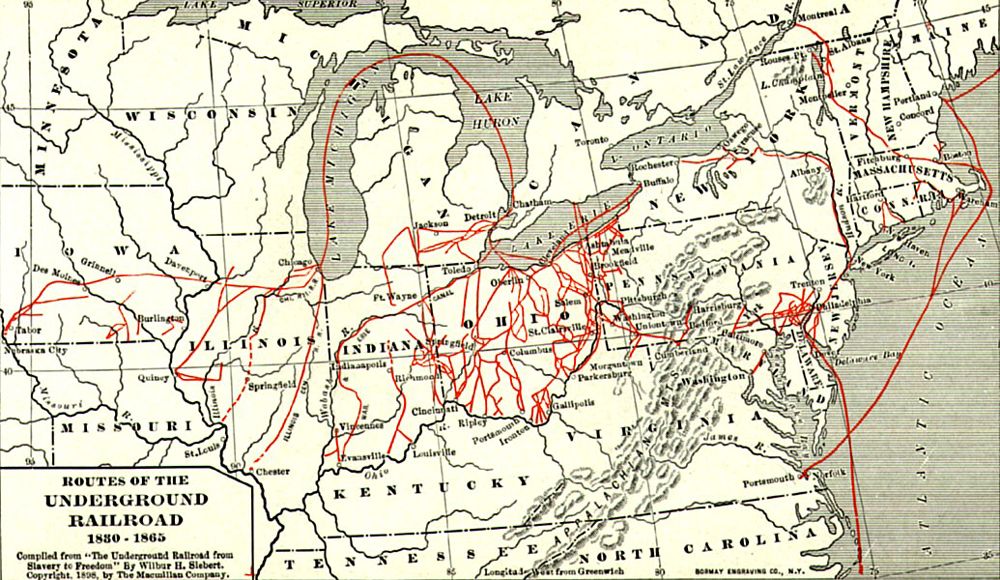

Though the institution of slavery was much larger in the South, especially during the 19th century, the Underground Railroad stretched the breadth and width of North America and to shores beyond. It sometimes existed openly in the North or just below the surface of everyday life in the Upper South. The term described locally organized activities, but with no real center or “headquarters,” per se. In its most developed form, the Underground Railroad offered local aid to runaways, assisting them from one point to another. “Conductors” would guide the freedom seekers to a safe “station” on the route North.

The underground system extended from Kentucky and Virginia across Ohio and from Maryland through Pennsylvania, New York, and New England to Canada. The field extended westward, and the territory embraced by the middle states and all the western states east of the Mississippi River was dotted with “stations” and covered with a network of imaginary routes not found in the railway guides or on the railway maps. Lines were formed through Iowa and Illinois, and passengers were carried from station to station until they reached the Canada line. Kansas was associated with Iowa and Illinois as a channel for the escape of runaways from the southwestern slave section. The Ohio-Kentucky routes probably aided more fugitives than any other. The valley of the Mississippi River was the most westerly channel until Kansas opened a bolder way of escape from the southwest.

The rapidity with which the term became commonly used around 1830 did not mean that incidents of resistance to slavery increased or that more attempts were made to escape from bondage. Freedom-seeking activity in North America began with the growth of slavery in the 17th century. It meant that more white northerners were prepared to aid freedom seekers and give assistance to northern African Americans who aided freedom seekers. On January 1, 1831, William Lloyd Garrison published the first issue of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. That event marks the traditional beginning of an open abolitionist attack on the institution of slavery.

In many cases, the decision to assist a freedom seeker may have been a spontaneous reaction as the opportunity presented itself. However, a series of events in the decade preceding the Civil War ignited Underground Railroad activity to unprecedented levels. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, part of the Compromise of 1850, marked the beginning of the most intensive era of Underground Railroad activity. To abolitionists, that law’s passage seemed to open the whole of the North to slaving excursions. Freedom seekers were no longer safe, even in abolitionist towns, as the might of the federal government backed the right of slaveholders to remove their alleged property to the South. This federal law mandated citizen assistance to slavers and allocated resources and men to ensure the return of human property to the South. The accused had no right to a jury trial, and commissioners appointed to adjudicate these cases received higher compensation for finding in favor of the slaveholder. With the enactment of the Fugitive Slave Act, abolitionists and sympathizers had to be willing to break federal law to assist freedom seekers. At that time, the Underground Railroad became deliberate and organized.

Despite the illegality of their actions and with little regard for their own personal safety, people of all races, classes, and genders participated in this widespread form of civil disobedience. Spanish territories to the south in Florida, British areas to the north in Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, and other foreign countries offered additional destinations for freedom. Free African American communities in urban areas in both the South and the North were the destination of some freedom seekers.

The Underground Railroad movement grew from small beginnings into a great system. It was primarily responsible for developing, if not in originating, the convictions of such powerful agents in the cause as Harriet Beecher Stowe and John Brown. It furnished the ground for the charge brought repeatedly by the South against the North of injury wrought by the failure to execute the law, a charge that must be placed among the chief grievances of the slave states at the beginning of the Civil War. The period, sometimes designated the “era of slave-hunting,” contributed to increasing the traffic along the numerous and tortuous lines of the Underground Railroad, which, according to the testimony of participants, did its most thriving business in all parts of the North during the decade from 1850 to 1860. When John Brown led his company of slaves from Missouri to Canada despite the attempts to prevent him, and when soon thereafter, he attempted to execute his plan for the general liberation of slaves, he showed the extreme to which the aid to fugitives might lead. The influence of his training in Underground Railroad work is plain in the methods and plans he followed.

The maritime industry was essential for spreading information and offering employment and transportation. Through ties to the whaling industry, the Pacific West Coast and perhaps Alaska became destinations. Military service provided another avenue, as thousands of African Americans joined the military from the colonial era to the Civil War to gain their freedom. During the Civil War, many freedom seekers sought protection and liberty by escaping to the lines of the advancing Union army.

The Underground Railroad, by its very existence, exposed the harsh realities of slavery. Slavery was not, as many slaveholders insisted, a benevolent institution that provided indolent African Americans with food and shelter. Beginning in the 1830s, slave owners portrayed African Americans as incapable of caring for themselves or organizing for the good of the community — all requirements for citizenship in a Republic. Slavery would Christianize and civilize the Africans, said slave-owning elites, and African Americans were content in bondage, a historical myth that lived long into the 20th century.

However, the Underground Railroad refuted these overtly racist claims that African Americans could not act or organize independently. Freedom seekers refuted the claim by Southern apologists that slavery was a “positive good” with their feet. Slaveholders sought to minimize the contrary view of slavery generated by freedom seekers in novel ways, such as the diagnosis of Samuel Cartwright at the University of Louisiana of “Drapetomania” — the disease that caused enslaved African Americans to run away.

The Underground Railroad gave ample evidence of African American capabilities. It also brought together, however uneasily, men and women of both races to work on issues of mutual moral concern. At the most dramatic level, the Underground Railroad provided stories of individual acts of bravery and suffering, guided escapes from the South, rescues of arrested freedom seekers in the North, and complex communication systems.

The Underground Railroad reached its height between 1850 and 1860. One estimate suggests that by 1860, 100,000 slaves had escaped via the “Railroad.”

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Also See:

Riding the Underground Railroad (historic text by Levi Coffin, 1850)

Harriet Tubman – Moses of the Underground Railroad

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

National Park Service