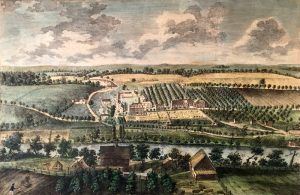

The Thirteen Colonies of what would later become the United States were firmly established by 1700 and exhibited few signs of the phenomenal growth that lay ahead. Fewer than 300,000 colonists occupied the scattered settlements along the Atlantic coast then. In the middle and southern colonies, where the coastal plain extended far inland, the settlement had just begun to spill beyond the fall line (head of navigation by seagoing vessels) toward the foothills of the Appalachians. Seventy-five years later, 2.5 million Americans blanketed the eastern seaboard and, here and there, had pushed even beyond the mountain barrier.

A high birth rate explained part of the population increase, for strong sons and healthy daughters were an obvious answer to the problem of the scanty labor supply. Vastly more important was a flood of immigration, part voluntary and part involuntary, that attained its greatest volume after the Peace of Utrecht in 1713, which ended the War of Spanish Succession in Europe. Afterward, many Rhineland Germans, Scotch-Irish, French Huguenots, Swiss, Irish, Scots, and Spanish and Portuguese Jews sought new lives in a new world.

The French Huguenots achieved disproportionate importance among the newcomers, even though they were few in number, because of their comparatively high level of culture and wealth. Essentially, urban dwellers were attracted to the more thickly settled areas. Almost every colonial city had its Huguenot contingent, but the real stronghold of the Huguenots was Charleston, South Carolina. By the middle of the 18th century, French influence had stamped itself upon the dress, manners, and architecture of Charleston.

The Germans settled largely in the middle and southern colonies and were far more numerous. Attempts were made to guide some of them into industry, but the vast majority preferred to push on to the frontier and become small farmers. Large numbers moved to the Pennsylvania frontier, where they acted as a valuable buffer for the older colonies to the east.

The Scotch-Irish were the most aggressive of the frontiersmen. They, too, found their way to the backcountry of the middle and southern colonies, chiefly Pennsylvania. Famed as Indian fighters, they helped to protect the older colonies, and, at the same time, because of their fiery temperament and frontiersman’s contempt for authority, they made infinite trouble for the governments nearer the coast.

Of the other immigrant groups, the Swiss settled mainly in the Carolinas, the Irish Catholics in Maryland and Pennsylvania, the Scots in Virginia, South Carolina, and Massachusetts; and the Jews in such metropolitan centers as Charleston, Philadelphia, New York, and Newport, Rhode Island.

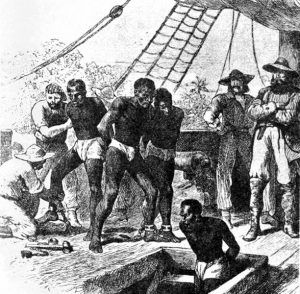

These people came of their own free will, but the largest non-English element in the colonies came involuntarily. By 1775, perhaps a fifth of the colonial population consisted of African American slaves. The spread of the plantation system in the southern colonies created a demand for slave labor. By the close of the colonial period, approximately six out of seven slaves resided south of the Mason-Dixon line. Slaves made up 40% of the population in Virginia and 60% in South Carolina.

Cities and towns reflected the population boom. In 1700, Boston was the colonial metropolis with 7,000 people, and only Philadelphia came close, with 5,000. By 1775, however, Philadelphia’s population had risen to 34,000, making her the largest city and 11 other cities had passed the 5,000 mark. During the same period, colonial towns increased in number by 3 and 1/2. However, the urban centers could accommodate only a fraction of the mushrooming population. The rest turned to the west and pushed beyond the 17-century colonial borders.

In 1700, settlements dotted the seaboard from Penobscot Bay, in present Maine, southward to the Edisto River in South Carolina. They were not continuous, and only in the valley of the Hudson River had they penetrated inland more than 100 miles. Seventy years later, however, settlement had spread down the coast another 150 miles, to the St. Marys River and inland 200 miles and more, to the crest of the Appalachians. At intervals, the restless frontier had swept beyond the Appalachian crest: in the south, to the headwaters of the Clinch and Holston Rivers; in the north, up the eastern shore of Lake Champlain and west along the Mohawk Valley, with the lonely outpost of Fort Ontario, on Lake Ontario; in the center was the French post of Fort Duquesne, and settlement continued 150 miles down the Ohio River.

The westward movement flowed continuously but not evenly. Before 1754, it was slowed by the hostility of Indian tribes angered by the English invasion and incited by French and Spanish agents. In western Pennsylvania, where Indian resistance was weaker than elsewhere, settlement had crossed the mountains before the outbreak of the French and Indian War. But during the next nine years, the frontier line receded to the east side of the Appalachians, and in 1763, with French power crushed, England sought to reserve the trans-Appalachian country to the Indians. The colonists were not to be stopped, however. Before the outbreak of the American Revolution, they were firmly established in the upper Ohio Valley.

Expansion and Conflict

The population growth and territorial expansion of the English colonies produced collisions. The French, the Spanish, and the Indians all contested English pretensions in the 18th century. The French proved most formidable. Numerically inferior to the English and scattered in tiny islands throughout the wilderness, they nevertheless possessed important advantages. They had an authoritarian rather than a representative government. While the English depended mainly on poorly trained militia led by inexperienced officers, the French fielded disciplined regulars commanded by the best officers in France. While the colonial legislatures haggled and denied money and troops, the French could efficiently manipulate their money, men, and supplies. And whereas the colonies dealt individually with the Indians, and for the most part tactlessly, the French executed a uniform Indian policy with some skill.

The earliest clash of the 18th century was Queen Anne’s War, which broke out in 1702. In this New World counterpart of the War of the Spanish Succession, the French and Spanish joined in an 11-year struggle with the English. On the southern borders of the English Colonies, South Carolinians in 1702 destroyed the Spanish town of St. Augustine and, in 1704, wrecked the Spanish mission system in western Florida. Two years later, they repulsed a joint French-Spanish attack on Charleston. On the northern borders, a series of barbarous French attacks on New England settlements, notably on Deerfield, Massachusetts, in 1704, led to a series of retaliatory expeditions against Port Royal, which was captured in 1710. The war finally ended with the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713.

The Treaty of Utrecht was designed to ensure peace by maintaining a balance of power, but it soon became evident that a piece of paper could not restrain the English colonists. In 1716, Virginia’s bold Lieutenant Governor, Alexander Spotswood, dramatized the possibilities of westward expansion by leading the “Knights of the Golden Horseshoe” across the Blue Ridge. Ten years later, New Yorkers ignored French claims and planted Fort Oswego on the shores of Lake Ontario. To the south, on lands claimed by Spain, James Oglethorpe founded a new English colony in present-day Georgia in 1733.

To Oglethorpe and his associates, Georgia was a humanitarian project designed to provide new lives for English debtors. To the English Government, it was a military outpost from which attacks could be launched against Spanish Florida. To the Carolinians, even though they lost valuable western lands as a result, it was a welcome buffer against the Indian attacks from which they periodically suffered. The Georgians and the Spanish Floridians immediately began trying to dislodge each other by force of arms. Neither succeeded. In the last of a series of expeditions against St. Augustine, in 1739-40, Georgians came within sight of their goal but failed to reach it. Spaniards fared no better. After an unsuccessful attempt to take the Georgia outpost of Fort Frederica in 1742, they gave up the effort to expel the intruders.

If less bloody, relations with the French along the western and northern frontiers of the English Colonies were equally explosive. France claimed everything west of the Appalachians by right of a tenuous occupancy of the Mississippi Valley, a claim that England refused to acknowledge because of the interests of her fur traders and land speculators. England finally moved in 1754 to strengthen the colonies for the approaching conflict. Two imperial Indian agents were appointed to coordinate and improve Indian policy. An overall commander, Major General Edward Braddock, took charge of the American military forces and, to counteract the advantage of the professional French Army, British regulars began to arrive in America.

The French and Indian War broke out early in 1754 when the French seized and fortified the forks of the Ohio River. Lieutenant Colonel George Washington marched west with a force of Virginia militia to contest the action. Still, it was besieged in Fort Necessity, southeast of the forks of the Ohio River, and was compelled to surrender. The following summer, General Braddock’s expedition against the French stronghold ended even more disastrously when the French and their Indian allies ambushed his command and all but annihilated it.

The English tried in vain for three years to drive back the French. Then, William Pitt rose to power in England in 1757. He named young and vigorous men to commands in America, and the tide turned. In rapid succession, the French strongholds fell to the English armies: Louisbourg, Fort Duquesne, Fort Frontenac, Fort Niagara, Fort Ticonderoga, Crown Point, Quebec, and finally Montreal itself. With the surrender of Montreal on September 8, 1760, the French gave up their claims to Canada and all its dependencies in North America. The war flared again, briefly, in 1761 when Spain came to the aid of France. The British, however, effortlessly seized Cuba and other Spanish possessions, and France and Spain had no choice but to sue for peace.

The Treaty of Paris, signed in 1763, ended the French and Indian War. Besides losing Canada, France surrendered the eastern half of the Mississippi Valley to England. For the return of Cuba, Spain had to relinquish Florida. To compensate her ally, France gave to Spain western Louisiana and the city of New Orleans. England thus emerged as the possessor of all North America east of the Mississippi River, and in the long run, her mainland colonies profited very signally. They could expand westward in comparative security no longer menaced by the French. They had gained valuable military experience and a new sense of solidarity from the war. Their ties with the mother country were weakened still further.

America Crosses the Mountains

In the year 1763, the western line of settlement stretched along the eastern base of the Appalachian barrier. Anglo-American frontiersmen had already penetrated the mountains beyond this line, exploring the interior rivers and trading for furs. This irregular penetration showed the way for the gathering flood of settlers who would soon pour through the mountains.

The fur interests vigorously opposed the overrunning of western preserves by settlers, who would inevitably drive away the Indian market. Balancing this influence, the land companies pressed to open new territories in the West. These and other interests were diligently at work while dogged pioneer farmers, who wanted only to find good land and build their homes, prepared to cross the mountains and claim the interior. The westward movement gathered momentum amid the clamor of land speculators and traders, presenting England with the bald fact that, no matter what the pressure groups wanted or her self-interest required, settlers would cross the mountains. The best that could be hoped for was the enactment of measures that would postpone Western settlement until a policy could be formulated that would satisfy the vested interests and lessen the mounting threat of full-scale war with the Indians.

The solution of the London policymakers was the Proclamation of 1763, which established the Appalachian highlands as the temporary settlement boundary on the western border of the Atlantic colonies. At the same time, the proclamation established the Province of Quebec northwest of the Ohio River; East and West Florida; and the vast region north of the Floridas, west of the Appalachians, and south of the Ohio River as a reservation for the Indians, with land purchases from them forbidden. The Proclamation of 1763 and subsequent efforts in the same direction were, for the most part, hardly more than gestures. Events had passed beyond the control of the British authorities, who but dimly understood the forces at work in the Colonies.

Decrees from faraway London, intended to control the westward movement, could neither deal effectively with the surge of immigrants nor prevent conflict with the Indians. Indian fear and resentment expressed itself almost immediately in the bloody Pontiac uprising of 1763-64. For a time, the frontier faced disaster, but the superior resources of the settlers ultimately prevailed, notably at the Battle of Bushy Run.

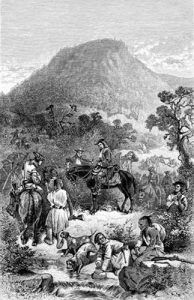

The tide of pioneers flowed through the mountain passes. Trading posts sprang up on the Ohio River below Fort Pitt, and the first settlement in the present State of Ohio was made at Schoenbrunn in 1772. In New York, the thin line of settlement that pointed west along the Mohawk spread north up the Hudson Valley and south toward the Delaware River. German and Scotch-Irish immigrants filled the fertile valleys of western Pennsylvania, and rude cabins dotted western Maryland and northwestern Virginia. Since the 1730s, settlers from Pennsylvania had streamed south and west to Springdale and other places in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. This valley, in turn, offered a natural highway to the Carolina Piedmont. From the farms and settlements of the Piedmont and Southern Highlands, colonists drifted into eastern Tennessee, along the Watauga River, and through Cumberland Gap into Kentucky.

War with Indian and European rivals, treaties with these nations, land speculation, and the ceaseless coming and going of the hunters and fur traders — all helped to plant the new frontier beyond the Appalachians. But the real strength of the westward advance lay in the sustained movement of thousands of settlers who left the safety of the colonies on the Atlantic or came directly from Europe to wrest a new life from the wilderness across the mountains. In the 18th century, the pattern of the frontier movement emerged. One day, it would carry the Nation to the Pacific.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

English Colonials to American Patriots

Settling America – The Proprietary Colonies

Source: National Park Service