Reverently called “Moses” by the hundreds of slaves she helped to free in the years preceding the Civil War, Harriet Tubman, was also a Union scout and spy, a humanitarian, and women’s suffrage advocate.

Harriet was born into slavery as Araminta Ross about 1820, in Dorchester County, Maryland, to parents Ben Ross and Harriet “Rit” Green. Like other slaves of the time, the exact place and date of her birth was not recorded.

Belonging to the Brodess family, Harriet’s mother worked as a cook in “the big house,” while her father was a skilled woodsman who managed the timber work on the plantation. One of nine children, she could only watch as her parents struggled in vain to keep the family together. Three of her sisters were sold, however, and she never saw them again.

As a child, Tubman was often hired out to other slave masters in the area and withstood beatings and whippings at their hands. As an adolescent, she suffered a traumatic head wound when she was hit by a heavy metal weight thrown by an irate overseer, intending to hit another slave.

Bleeding and unconscious, Tubman was returned to her owner’s house, where she lay without medical care for two days. Though the injury caused disabling seizures, blackouts, and severe headaches, which she would suffer for the rest of her life, she was soon sent back into the fields. When her field boss began to complain, the Brodess family tried unsuccessfully to sell her. The injury also caused Tubman to have strange visions and dreams, which she believed were signs from the divine, guiding her “missions” in her later life.

In about 1844, she married a free black man named John Tubman. Little is known about him or their marriage, which had to have been complicated by her slave status. Soon afterward, she adopted her mother’s name of “Harriet.” In 1849, she became very ill, and the Brodess family again tried to sell her. She then determined that she would escape, later saying: “There was one of two things I had a right to — liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other.”

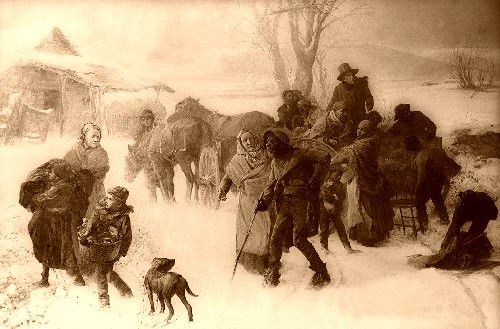

Escaping with the help of the Underground Railroad, through an elaborate and secret series of houses, tunnels, and roads set up by abolitionists and free and former slaves, she made her way to Philadelphia.

There, she worked various odd jobs and joined a large abolitionist group. The following year, she joined the Underground Railroad and, on her first mission in December 1850, returned to Maryland to rescue her sister and her sister’s children. In the Spring of 1851, she headed back to Maryland, freeing her brother Moses and two other men. Though Tubman sent word to her husband that he should join her, he insisted that he was happy where he was. That fall, she returned to John, only to discover that he had married another woman.

Over the next decade, she would travel to the South about 18 times, helping some 300 slaves escape via the secret routes and safe houses established by the Underground Railroad. During this time, she also freed three of her brothers, Henry, Ben, and Robert, their wives, and some of their children. As she led more and more individuals out of slavery, she became popularly known as “Moses.” In 1857, though her aging parents had already been freed, she led them north into the Canadian city of St. Catharines, Ontario, where a community of former slaves, including her brothers, other relatives, and many friends, had gathered.

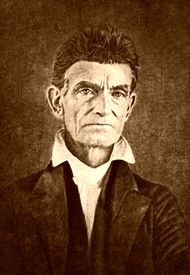

In April 1858, Tubman was introduced to the radical abolitionist John Brown, who advocated using violence to destroy slavery. Though she didn’t agree with his tactics, she supported his goals and helped him plan and recruit for the raid at Harpers Ferry. Her knowledge of support networks and resources in the border states of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware was invaluable to Brown and his planners. However, she was not present at the attack that failed on October 16, 1859. John Brown was convicted of treason and hanged in December. Tubman would later tell a friend, “He done more in dying than 100 men would in living.”

In the meantime, Tubman had purchased a small piece of land on the outskirts of Auburn, New York, a city known for its antislavery activism. She soon moved her parents out of the harsh Canadian winters to her place in New York, as well as other family members and friends. Her land soon became a haven for relatives and boarders alike, offering a safe place for black Americans seeking a better life in the north. She conducted her last rescue mission in November 1860.

When the Civil War broke out, Tubman volunteered for the Union Army, where she first worked as a cook and a nurse. She soon became a fixture in the camps, especially in South Carolina. By 1863, she was working as a scout, where her knowledge of covert travel and subterfuge among potential enemies was put to good use.

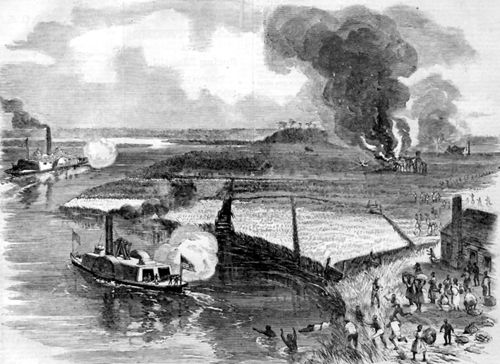

When Colonel James Montgomery and his troops conducted an assault on a collection of plantations along the Combahee River in South Carolina, Tubman served as a key adviser and accompanied the raid. On June 2, 1863, Tubman guided three steamboats around Confederate mines in the waters leading to the shore. The Union troops then fired on the plantations, seized thousands of dollars worth of food and supplies, and freed more than 700 slaves. Harriet Tubman was heralded in the newspapers for her patriotism in the Combahee River Raid. She later worked with Colonel Robert Gould Shaw at the assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, reportedly serving him his last meal.

Montgomery’s Raids on the Combahee River Plantations

Harriet continued to work for the Union until the war was finally over. Despite her years of service, she had never received a regular salary and was for years denied any compensation until she finally received a pension in 1899. She spent her remaining years in Auburn, tending to her family and other people in need. To provide for herself and her parents, she worked at various jobs and took in boarders. One boarder was a Civil War veteran named Nelson Davis, who she married on March 18, 1869, despite the fact that he was 22 years younger than her. In 1874, they adopted a baby girl named Gertie.

Harriet also got involved in the Women’s Suffrage movement, working alongside women such as Susan B. Anthony and Emily Howland. When the National Federation of Afro-American Women was founded in 1896, she was the keynote speaker at its first meeting. This wave of activism kindled a new wave of admiration for Tubman among the press in the United States.

As Harriet grew older, she continued to have problems from her head injury as a child. At some point in the late 1890s underwent brain surgery at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital. During the surgery, she received no anesthesia for the procedure and reportedly chose instead to bite down on a bullet, as she had seen Civil War soldiers do when their limbs were amputated.

At the turn of the century, Tubman became heavily involved with the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Auburn and in 1903, donated a parcel of land to develop a home for “aged and indigent colored people.” It opened five years later and was named the Harriet Tubman Home.

Harriet Tubman

By 1911, she had become so frail that she had to be admitted into the rest home named in her honor. A New York newspaper described her as “ill and penniless,” which prompted supporters to offer a new round of donations. Surrounded by friends and family members, Harriet Tubman died of pneumonia on March 10, 1913. Just before she died, she told those in the room: “I go to prepare a place for you.”

She was buried with military honors at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, New York.

Widely known and well-respected while she was alive, Harriet Tubman became an American icon in the years after she died. She inspired generations of African Americans struggling for equality and civil rights and was praised by leaders across the political spectrum.

Throughout the years, several schools have been named in her honor, including a military ship, several monuments, and two museums. At the 100th anniversary of her death, the state of Maryland has named a state park after her, and as of this update, the US Congress is considering naming a National Park for her.

On April 20, 2016, the U.S. Treasury announced that Tubman would replace the 7th U.S. President, Andrew Jackson, on the $20 bill. Jackson’s face has been on the bill since 1928. The final concept designs for the new bill are expected in 2020 in honor of the 100th Anniversary of the 19th Amendment to the Bill of Rights, which gave women the right to vote in the U.S.

Although historians have debated facts, like the number of people she actually led to freedom, or the amount of the bounty once put on her head, her achievements through adversity remain an inspiration to all.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2022..

Also See:

The Underground Railroad – Flight to Freedom

John Brown – Crusading Against Slavery

Civil War People, Soldiers & Officers Photo Print Gallery