“… Wild Bill had his faults, grievous ones, perhaps … He would get drunk, gamble, and indulge in the general licentiousness characteristic of the border in the early days, yet even when full of the vile libel of the name of whiskey which was dealt over the bars at exorbitant prices, he was gentle as a child unless aroused to anger by intended insults. … He was loyal in his friendship, generous to a fault, and invariably espoused the cause of the weaker against the stronger one in a quarrel.”

— Captain Jack Crawford, who scouted with Wild Bill before they both followed the gold rush to Deadwood.

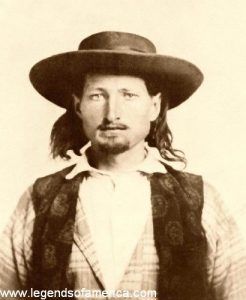

James Butler Hickok, better known as “Wild Bill,” was a wagon master, soldier, scout, lawman, gunfighter, gambler, showman, and actor well-known in the American West.

James Butler Hickok was born in Troy Grove, Illinois, on May 27, 1837, to William Alonzo Hickok and Polly Butler Hickok. Bill had four brothers and two sisters, and his parents were devout Baptists who expected him to fulfill his chores on the farm and attend church every Sunday.

His parents also operated a station along the Underground Railroad, where they smuggled slaves out of the South. During this time, the lean and wiry young man got his first taste of hostile gunfire when he and his father were chased by law officers who suspected them of carrying more than just hay in their wagon. Bill became enamored with guns and began target practice on small wildlife around the farm. His romantic notions of the Wild West never sat well with his father, but Bill became locally recognized as an outstanding marksman even in his youth, despite his father’s protests.

At the age of 14, Bill’s father was killed because of his stand on abolition. Three years later, when Bill was 17, he began working as a towpath driver on the Illinois and Michigan Canal. However, a year later, he headed to Kansas to get a job in Monticello, in Johnson County, driving a stagecoach on the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails. One of the first people he met in Kansas was Bill Cody, who would later claim fame with his Buffalo Bill Wild West Show.

In 1855, stagecoaches were often subject to threats from bandits and Indians along the trail, and Bill quickly put his marksmanship to work, developing a readiness to defend against the frequent attacks. On one such overland trip, the stage broke down near Wetmore, Colorado. As Wild Bill slept under some bushes outside, the customers stayed within the coach until a disturbance awakened them. One of the travelers lit a kerosene lantern to find Bill being attacked by a cinnamon bear. When the struggle between man and bear was over, Bill was severely wounded, but the bear lay dead on the ground from Hickok’s six-inch knife.

After recovering from the almost lethal attack, Wild Bill returned to Monticello, Kansas, where he accepted a position as a peace officer on March 22, 1858. Sometime after that, he worked for the Pony Express and Overland Express station in Rock Creek, Nebraska, where he met David McCanles. McCanles teased Hickok unmercifully about his girlish build and feminine features. Perhaps in retaliation, Hickok began courting a woman named Sarah Shull, whom McCanles had been eyeing.

On July 12, 1861, McCanles, his young son, and two friends, James Woods and James Gordon, came to the station, supposedly to collect a debt. However, profanities were exchanged, which resulted in gunfire. McCanles was killed, and James Woods and James Gordon, who were seriously wounded, later died of their wounds. No charges were made against Hickok on the grounds of self-defense. Later, when Hickok’s fame began to spread, writers looked back and began to call this gunfight the “McCanles Massacre,” embellishing the story to the point that Wild Bill had polished off a dozen of the West’s most dangerous desperados.

Hickok moved on again, landing in Sedalia, Missouri, where he signed on with the Union Army as a wagon master and scout on October 30, 1861. The military records of his service provide very little information. Still, we know that Hickok received the nickname “Wild Bill” while serving in the Union Army. As the story goes, he was in Independence, Missouri, when he encountered a drunken mob with intentions of hanging a bartender who had shot a hoodlum in a brawl. Hickok fired two shots over the heads of the men, staring them down with a glare until the mob dispersed. A grateful woman shouted from the sidelines, “Good for you, Wild Bill!” She may have mistaken Hickok for someone else, but the name stuck.

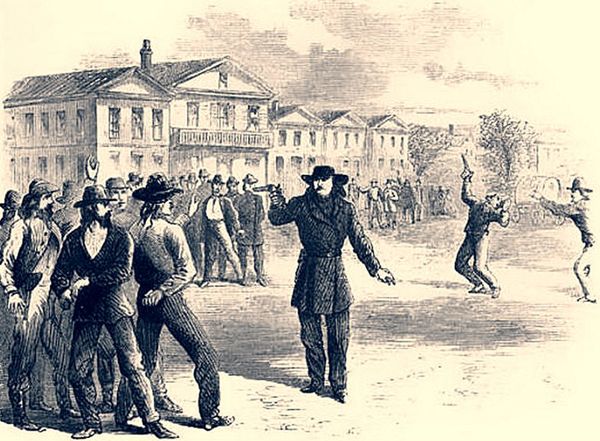

After the Springfield, Missouri, shootout, Hickok turned on Tutt’s friends, as illustrated in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867.

In July of 1865, Hickok met up with a twenty-six-year-old gambler in Springfield, Missouri, to whom Hickok lost at the gaming table. When Bill couldn’t pay up, Dave Tutt took his pocket watch for security. Hickok growled that if Tutt so much as used the timepiece, he would kill him.

On July 21, 1865, the two met in the public square, Tutt proudly wearing the watch for all to see. Moments later, Tutt lay on the ground dead. Hickok was acquitted of any wrongdoing.

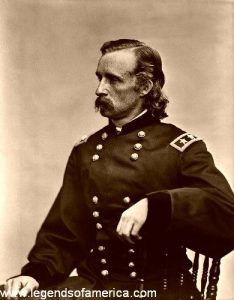

While in the Army, Hickok became good friends with General George Custer, working as one of his principal scouts. Custer was said to have admired Hickok, played poker with him, and would have known him better had it not been for the disaster at the Little Bighorn.

Shortly after the war, in 1867, Hickok was tracked down by Henry M. Stanley, a correspondent for the New York Herald who later went to Africa and “found” Dr. Livingstone. Hickok blithely told the gullible Stanley that he had personally slain over 100 men. Stanley immediately reported this claim as gospel fact, and Wild Bill became a national legend.

On November 5, 1867, Wild Bill ran for sheriff of Ellsworth County, Kansas, but lost. He returned to the army, where he was lanced in the foot during a skirmish with an Indian in eastern Colorado. Returning to Kansas, he became the sheriff of Hays City in 1869. On August 24, 1869, he shot and killed a man named Bill Mulrey. Just a month later, on September 27, 1869, he killed a ruffian named Strawhan when he and several others were causing a disturbance in a local saloon.

On July 17, 1870, the real trouble started for Hickok when several members of the 7th U.S. Cavalry caught him off guard in Drum’s Saloon, knocked him to the floor, and began kicking him. Hickok drew his pistols, killing one private and seriously wounding another. After this skirmish, Bill resigned from his position in Hays City, returned to Ellsworth, Kansas, for a time, and then moved on to Abilene, Kansas.

On April 15, 1871, Hickok was appointed city marshal in Abilene for $150 per month, plus one-fourth of all fines assessed against the persons he arrested. At first, Wild Bill tended to routine business.

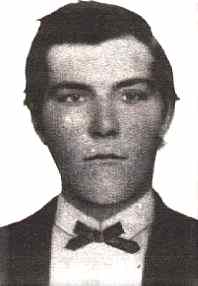

John Wesley Hardin

When John Wesley Hardin, purportedly the worst killer in the Wild West, arrived in Abilene, Wild Bill allegedly took an indulgent and parent-like attitude toward the nasty little murderer. Hardin would later say that they drank together, visited the brothels together, and Hickok often gave him advice. Hardin enjoyed being seen with the celebrated gunfighter. Still, he was also cautious around the city marshal, sure that if he got seriously out of line, Wild Bill would add him to his reputation.

However, it didn’t take long before Hardin crossed the line. Sleeping at the American House Hotel, he was awakened by snoring coming from the next room. Angry at having been awakened, Hardin fired shots through the wall. In the deathly silence, Hardin knew that Marshal Hickok would waste no time in chasing him down.

According to Hardin, he crawled out a window onto the roof dressed only in his undershirt, spotted Wild Bill approaching, and dove from the roof into a haystack, where he hid for the rest of the night. Hardin emerged with the dawn, stole a horse, and hightailed it out of town dressed only in his underclothes. Hardin’s account of his interaction with Hickok cannot be corroborated through any records of the time, and grave doubt has been cast on his account.

A local newspaper complained that Hickok allowed Abilene to be overrun with gamblers, con men, prostitutes, and pimps.

Hickok gradually spent more time at the gaming tables and with the ladies of the evening than he did attending to his sheriff duties. One young man in Abilene by the name of Samuel Henry described Hickok’s gambling habits as:

“His whole bearing was like that of a hunted tiger—restless eyes, which nervously looked about him in all directions, closely scrutinizing every stranger. When he played cards, which he did most of the time in the saloons, he sat in the corner of the room to prevent an enemy from stealing up behind him.”

Vintage Abilene, Kansas.

However, Wild Bill did have some marshaling to do, and the Bull’s Head Saloon gave him the most trouble. Phil Coe and Ben Thompson, gamblers and gunmen, were the saloon owners, and what brought matters to a head was an oversized painting of a Texas Longhorn painted in full masculinity. Most Abilene townspeople were offended by the sign and demanded the animal’s anatomy be altered; Hickok stood by with a shotgun as the necessary deletions were made to the painting. Later, Thompson left town, and Coe sold his interest in the saloon, although he remained a gambler. When Hickok and Coe began to court the same woman, rumors circulated that each planned to kill the other.

On October 5, 1871, the trouble finally came to a head. Many cowboys were in town, fighting, drinking, and carousing, and only Deputy Mike Williams offered Hickok his assistance. Coe was celebrating the end of the cattle season, and when he and his friends neared the Alamo Saloon, a vicious dog tried to bite him, prompting Coe to take a shot at the dog.

Though he missed the dog, Hickok appeared just minutes later to investigate the shots. Upon Coe’s explanation, Wild Bill explained to Coe that firearms were not allowed in the city, but for whatever reason, all hell broke loose, and Coe sent a bullet Hickok’s way. Bill returned the fire and shot Coe twice in the stomach. Suddenly, Hickok heard footsteps coming up behind him, and turning swiftly, he fired again and accidentally killed Deputy Mike Williams. Coe died three days later. Abilene had had enough. The city fathers told the Texans there could be no more cattle drives through their town and dismissed Hickok as city marshal.

At about this time, the East Coast was thriving on the Wild West stories in dime novels that were being churned out, as well as the exaggerated articles displayed in the press. Having had some luck at the gaming tables, Hickok joined the foray and put together a show called “The Daring Buffalo Chase of the Plains” in the early 1870s. Making a thousand-dollar investment, he packed up six buffalo, four Comanche Indians, three cowboys, a bear, and a monkey and headed to Niagara Falls, New York, by train. But the show was a disaster. The once frisky buffalo acted like Jersey cows until Wild Bill fired a shot. Suddenly, the buffalo ran circles with the Comanche screaming in pursuit, some stray dogs mixed into the fray, several children chased by their parents, and all hell broke loose. Suddenly, the buffalo broke through a wire fence and stampeded the audience. Wild Bill made only a little over $100 for his show and had to sell the buffalo to a butcher shop to cover the expenses of getting back home for everybody.

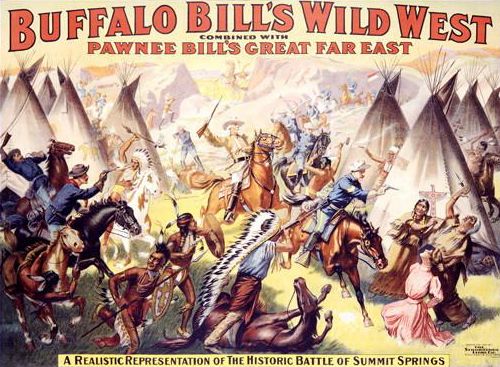

However, his old friend, Buffalo Bill Cody, came to his rescue. Inviting Hickok to join his dramatic play entitled “Scouts of the Prairies,” Wild Bill made a decent income and was able to indulge in his love for women and gambling, but as an actor, he was not. Nor was he happy; beginning to drink excessively, his acting became even worse. Finally, in March 1874, he said goodbye to Cody and headed back out West.

Buffalo Bill Cody recreates the Summit Springs Battle.

On March 5, 1876, Hickok married Agnes Lake Thatcher, an older woman who had been chasing him around the country for years and patiently waiting for him to tire of his long string of female companions.

By this time, he was almost 39, going bald, wearing glasses, and was said to have sensed his oncoming death. Marrying in Cheyenne, Wyoming, the two traveled to Cincinnati, Ohio, for their honeymoon. Just a month later, Bill explained that he was headed to the western goldfields to make a grubstake and would send for her later. She would never see him again.

When Hickok accompanied Charlie Utter’s wagon train to Deadwood, South Dakota, his reputation as a gunfighter had preceded him. Initially, he attempted to lead a quiet, reasonably respectable life in the wild mining camp. Still, his two most significant failings – gambling and liquor- led him into the rough saloons lining the main street of the narrow gulch.

Along the wagon train trail to Deadwood, Hickok met Calamity Jane in Laramie, Wyoming. Being very much alike in their outrageous tales and heavy drinking habits, the two hit it off immediately. Later, Calamity Jane would tell everyone they were a “couple,” but this has been much disputed.

Seemingly uninterested in a grubstake, Wild Bill tried vainly to resume a gambling career but no longer possessed the requisite skills. In fact, he could barely keep himself properly suited and situated to hold on to the reputation and the illusion. He was seldom sober and was repeatedly arrested for vagrancy.

On August 1, 1876, Hickok was playing poker in a Deadwood saloon with several men, including Jack McCall, who lost heavily. Wild Bill generously gave him back enough money to buy something to eat, but advised him not to play again until he could cover his losses.

The next afternoon, August 2, when Wild Bill entered Nuttall & Mann’s Saloon, he found Charlie Rich sitting in his preferred seat. After some hesitation, Wild Bill joined the game, reluctantly seating himself with his back to the door and the bar — a fatal mistake. Jack McCall, drinking heavily at the bar, saw Hickok enter the saloon, sitting at his regular table in the corner near the door.

McCall slowly walked around to the corner of the saloon where Hickok was playing his game. From under his coat, McCall pulled a double-action .45 pistol, shouted, “Take that!” and shot Wild Bill Hickok in the back of the head, killing him instantly. Hickok had been holding a pair of eights and a pair of Aces, which has ever since been known as the “dead man’s hand.”

Hickok’s good friend, Charlie Utter, claimed the body, made the funeral arrangements, and bought the burial plot. He was buried in the cemetery outside Deadwood on August 3, 1876. Calamity Jane insisted that a proper grave be built in honor of the man she loved, and a 10-by-10-foot enclosure was constructed around his burial plot, encircled by a three-foot fence featuring fancy cast-iron filigree on top. A small American flag was stuck into the ground in front of the tombstone in honor of his service in the War.

The entire population of the gulch, from prospectors to prostitutes, followed his funeral procession to “Boot Hill.” Charlie Utter placed a wooden marker on the grave, inscribed:

Wild Bill B. Hickok

Killed by the assassin Jack McCall

Deadwood, Black Hills

August 2, 1876

Pard, we will meet again in the

Happy Hunting Grounds to part no more

Goodbye

Colorado Charlie, C. H. Utter

Soon, his new bride would receive a letter Bill had penned just one day before his death. Seemingly, it appears that he had a premonition of his rapidly approaching demise:

“Agnes Darling, if such should be, we never meet again while firing my last shot, I will gently breathe the name of my wife — Agnes — and with wishes, even for my enemies, I will make the plunge and try to swim to the other shore.”

The day after Hickok was killed, a jury panel was selected to try Jack McCall. McCall claimed he had shot Wild Bill in revenge for killing his brother back in Abilene, Kansas, and maintained that he would do it all over again given a chance.

In less than two hours, the jury returned a “not guilty” verdict that evoked this comment in the local newspaper: “Should it ever be our misfortune to kill a man … we would simply ask that our trial may take place in some of the mining camps of these hills.”

McCall stayed in Deadwood for several days until California Joe, a man who had lived there, suggested that the air might be detrimental to McCall’s health. McCall got the message and, believing he’d escaped punishment for his crime, headed to Wyoming, bragging to anyone who would listen that he had killed the famous Wild Bill Hickok.

Calamity Jane at Wild Bill Hickok’s Grave.

Less than a month later, the trial held in Deadwood was found to have had no legal basis because Deadwood was located in “Indian Territory.” McCall was arrested in Laramie, Wyoming, on August 29, 1876, charged with murder, and taken to Yankton, South Dakota, to stand trial.

Lorenzo Butler Hickok traveled from Illinois to attend the trial of his brother’s murderer and was gratified by the guilty verdict. On March 1, 1877, Jack McCall was put to death by hanging. As to McCall’s earlier claim of having shot Hickok out of revenge for his brother, it was later discovered that Jack McCall never had a brother.

Years after Hickok’s death, in 1900, an aging Calamity Jane arranged to be photographed next to his overgrown burial site. Elderly, thin, and poor, her clothes were ragged and held together with safety pins. Holding a flower in her hand, she said that she wanted to be buried next to the man she loved when she died. Three years later, she was.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated September 2025.

Also See:

Calamity Jane – Rowdy Woman of the West

Deadwood – Rough & Tumble Mining Camp

McCanles Massacre – A WPA Interview

Rock Creek Station & the McCanles Massacre

Wild Bill – 1867 Harper’s Weekly Article

See Sources.

Another fun video from our friends at Arizona Ghost Riders: Aces and Eights…Dead Man’s Hand