Hiram Scott, a Mountain Man, trapper, and trader, was born about 1805 in St. Charles County, Missouri, and grew up to join William Henry Ashley’s Rocky Mountain Fur Company. Described as an unusually tall and muscular man of dark complexion, his first adventure was Ashley’s Expedition up the Missouri River in 1822-23. On June 1, 1823, he was known to have taken part in a battle of the Arikara War, which resulted in about a dozen of the traders’ deaths.

In 1826, he is thought to have attended the first fur trader rendezvous held near Great Salt Lake, Utah, and it has been assumed that he attended those held in 1827 and 1828. In 1827, he was still working for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company as a clerk and a leader to some degree. As a clerk, he was responsible for keeping track of the many transactions made with the Indians, inventory, and payroll.

In 1828, as he returned to St. Louis, Missouri, from the 1828 rendezvous, he died near Scotts Bluff, Nebraska. The bluff was named in his honor. The story of how he died has several versions, but he was apparently too ill to travel and was abandoned by his companions. His bones were found many miles from where he had been deserted the following season.

The story of Scott’s death was first recorded by Warren A. Ferris, an employee of the American Fur Company, who traveled through the area in 1830. He related that during Scott’s eastward journey, he had contracted a severe illness. Two comrades placed him in a boat and attempted to transport him downstream. However, the two men abandoned Scott on the north bank of the Platte River for some unknown reason. The following spring, Scott’s skeleton was found on the other side of the river, implying that he had somehow managed to cross to the opposite bank before he died.

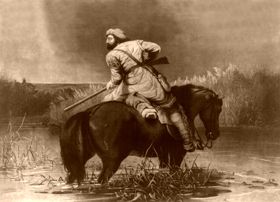

Hiram Scott.

A subtle variation of this story was recorded two years later by Washington Irving. Instead of being abandoned by just two men, the ailing Scott was supposedly left behind at the Laramie Fork by a larger party who feared for their lives due to starvation. The following summer, Scott’s bones were found near the bluffs, 60 miles from where he had been left to die.

In 1834, missionary Jason Lee recorded a story about Hiram Scott similar to those earlier versions, except that the pathetic Scott had traversed 100 miles before dying near the bluffs on the North Platte River.

The story of what happened to Hiram Scott was told and retold over the years, with more variations. Some stories included dramatic attacks by Indian warriors, while others suggested murder and foul play. Some stories include the noble theme of the doomed Scott insisting that his comrades leave him behind so they might save themselves from his fate.

There has been some speculation that Hiram Scott was injured in an encounter with some Blackfeet Indians at the 1828 rendezvous at Bear Lake, Utah. This has been used to explain why Scott became incapacitated on his journey back east, but as with most of the information about Hiram Scott, very little is known for sure.

Though history has become hopelessly confused, research has proved that Hiram Scott was prominent in the Rocky Mountain fur trade from 1823 until 1827, and disappeared in 1828 and was never heard from again. His companions remain unidentified, but research strongly suggests that William Sublette was the leader of the 1828 caravan, who instructed these men to remain with him. William Sublette also led the springtime caravan of 1829 that discovered Scott’s skeleton miles away from the spot where they reported he had died.

Almost immediately after his death, the bluffs along the North Platte River in Nebraska became known as Scotts Bluff. In 1830, the first wagons made the overland trip on the same route used by early fur traders like Hiram Scott, and the bluffs that bear his name served as a landmark for people making their way west.

The fur trade continued for a decade after Hiram Scott died in 1828, but by 1840, the beaver had been trapped out, and fashions had changed, as men were then wearing hats made of silk instead of beaver fur, and the value of furs dropped.

Hiram Scott’s final resting place is not known. His remains were almost certainly found near the North Platte River, but the site has never been located. Today, a plaque dedicated to his memory is located along the North Overlook Trail on the bluff’s summit that bears his name.

No willing grave received the corpse

of this poor lonely one;—

His bones, alas, were left to bleach

and moulder ‘neath the sun!

The night-wolf howl’d his requiem,—

the rude winds danced his dirge;

And e’er anon, in mournful chime

sigh’s forth the mellow surge!

The spring shall teach the rising grass

to twine for him a tomb;

And, o’er the spot where he doth lie,

shall bid the wild flowers bloom.

But, far from friends, and far from home,

ah, dismal thought, to die!

Ah, let me ‘mid my friends expire,

and with my fathers lie.

— Rufus B. Sage, a pioneer who passed the bluff in 1841, was inspired by Scott’s death.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2025.

Also See:

List of Old West Explorers, Trappers, Traders & Mountain Men

The Rocky Mountain Fur Company

Scotts Bluff – Towering over the Nebraska Plains

Primary Source: National Park Service