Towering 800 feet above the North Platte River, Scotts Bluff, Nebraska, has been culturally and historically significant for centuries. First serving as a landmark for Native Americans, the bluff was such a prominent focal point that more than 50 pre-contact archeological sites lie within its shadow. Later, it served as a pathmark for the hundreds of thousands of emigrants who traveled westward on the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails, as well as the riders of the Pony Express.

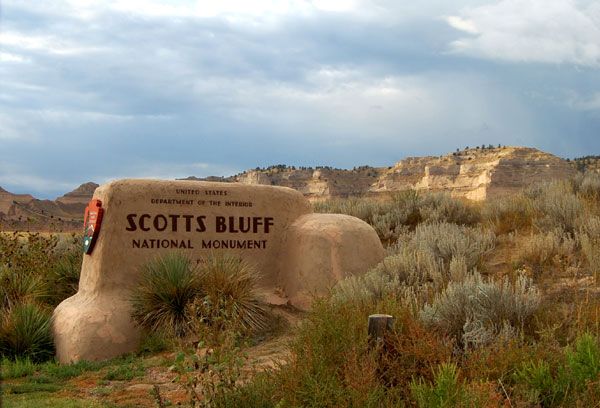

Scotts Bluff National Monument preserves 3,000 acres of unusual land formations that rise over the otherwise flat prairie below. At 4,659 feet above sea level, Scotts Bluff, the adjoining Wildcat Hills, and nearby Chimney Rock, Courthouse, and Jail Rock have been and continue to be weathered out of geologic deposits.

Wind and stream deposits of sand and mud, wind deposits of volcanic ash, and supersaturated groundwater rich in lime formed the layers of sandstone, siltstone, volcanic ash, and limestone that now comprise Scotts Bluff’s steep elevation, ridges, and broad alluvial fans at its base. The geological deposits then began to erode gradually, except at specific locations protected by a caprock of hard limestone more resistant to erosion. This caprock covers the tops of the bluffs in the area, slowing their erosion rate, which resulted in the area’s unique geologic features.

Much of the West, including the Scotts Bluff area, remained essentially unknown to white men until the early decades of the 19th century, when trappers, traders, missionaries, gold-seekers, soldiers, homesteaders, and others came to the region. Before this time, however, many Indian tribes made their homes in the region, including the Arapaho, Arikara, Cheyenne, Crow, Hidatsa, Kiowa, Mandan, Pawnee, Ponca, and Shoshone, among others. Later, beginning in about 1685, the Sioux tribes began to push into the area from the Great Lakes region and, by the late 1800s, dominated the area from Minnesota to Yellowstone.

Although Spain and France claimed portions of the American West before the 19th century, they left much unexplored. When President Thomas Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, white exploration of the West began in earnest. The early reports from government-sponsored expeditions, such as those of Lewis and Clark (1803 to 1806) and Zebulon Pike (1806 to 1807), testified to the bounty of natural resources in the West, from which trappers and traders soon began to profit.

The first fur trappers passed through the Scotts Bluff region during the Astorian Expedition in 1811-1813. This expedition traveled to the Pacific Coast, taking a route that would later become the Oregon Trail. In 1828, a fur trapper named Hiram Scott died at the bluff. Too ill to travel, he was abandoned by his companions. His bones were found the following year many miles from where he had been deserted. The bluff is named for this forgotten mountain man. Hundreds of trappers and traders followed the

The Astorian/Oregon route along the Platte River until the 1830s when fur trapping peaked.

In the 1840s, emigrants replaced trappers on the westward trails. In 1841, the first group of emigrants, a wagon train of 80 people known as the Bidwell-Bartleson Party, passed through the Scotts Bluff region to settle in the fertile farmland of the Willamette Valley in Oregon. Accompanying the party was well-known Catholic missionary Father Pierre-Jean De Smet. Missionaries had long traveled throughout the western wilderness seeking American Indian converts and were among the first travelers along the Oregon Trail. As homesteaders sent positive reports of the Oregon territory back east, interest in the region spread, and more settlers embarked on the arduous journey.

The number of emigrants using the trail peaked in 1852 when more than 70,000 went west, most of whom traveled through the North Platte River Valley on their 2,000-mile trek west. Most of the pioneers bound for Oregon were families seeking farms. Wagon trains, usually comprised of multiple families, embarked in late April or early May, each guided by a train leader. Emigrants had three primary needs on their journey: food for their company, grazing lands for their animals, and good, safe campsites. With wagons pulled by oxen, the trains could travel 15 to 20 miles a day across the plains but made significantly fewer miles in the mountains. The trek took up to six months.

The journey west was not for the faint of heart. Difficulties ranged from relatively minor, such as boredom or the irritation of the dust kicked up by the feet of hundreds of oxen, to more threatening environmental disasters.

More significant threats included starvation, dehydration, exhaustion, and disease; cholera alone killed thousands of travelers. Out of a total of roughly 350,000 emigrants, about 20,000 people died during their journey.

Violence resulting from tensions between settlers and travelers and the Plains Indians was also a danger. At night, the wagon convoys formed into protective circles as bulwarks against possible Indian attack. White travelers and settlers reduced the number of buffalo, encouraging intertribal war over hunting grounds, which in turn caused more danger to settlers. White travelers also brought new diseases with them, wiping out large numbers of Great Plains Indians. The ever-increasing number and size of homesteads on the plains and irrigation projects for farming further threatened buffalo populations and Indian territory.

In addition, settlers often established homesteads or towns on land set aside for Indians by the United States Government. The tensions often erupted into wars throughout the 19th century, when circumstances provoked both sides to attack in a series of bloody confrontations and massacres throughout the West.

More than 70,000 Mormons crossed Nebraska’s North Platte River Valley, seeking religious freedom in the West. In 1846, following the murder of their founder, Joseph Smith, the Mormons were driven out of Nauvoo, Illinois. Led by Brigham Young, who became the president of the Church of the Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints after Joseph Smith’s death, the group found refuge in the Salt Lake City area in modern-day Utah. Mormon converts continued to move into the Salt Lake Valley over the next few decades. At first, the Mormon Church created an emigration fund to assist those who had difficulty making the dangerous and costly journey due to illness or poverty. However, as thousands of Mormons utilized the aid, funds became scarce, and Young decided to provide less expensive handcarts instead of wagons.

As a result, many of those on the Mormon Trail who could not obtain a wagon went to Salt Lake on foot, pushing carts laden with their possessions. The Mormon handcart migration continued until the advent of the railroad in the late 1860s.

In 1849, the largest wave of migration to the West began. In 1848, James W. Marshall discovered gold in California at Sutter’s Mill. Tens of thousands of “forty-niners,” named for the first year of the gold rush, joined the exodus to California to seek their fortunes. Unlike settlers headed to Oregon, who often traveled in family units, most “forty-niners” were young men, either unmarried or unaccompanied by wives. The most commonly used route to the California goldmines followed the Oregon Trail west through the Scotts Bluff area and turned southwest toward California at Fort Hall, Idaho. The gold rush became the largest overland trail migration in American history. In 1850 alone, nearly 55,000 emigrants passed through the Platte Valley, most headed to California. By 1853, the gold rush slowed as easily accessible gold deposits ran dry, and most emigrants traveling along the trail were once again homesteaders and not gold-seekers.

Geographical landmarks, often colossal rock formations, were important to overland travelers and often used as benchmarks of the journey. Scotts Bluff was well known to travelers on the trail. Many westward pioneers romanticized the grandeur of Scotts Bluff in their diaries. The landmark was a welcome sight after miles and miles of flat prairie land, and only Chimney Rock was mentioned more often. Other nearby recognizable rock formations included Courthouse and Jail Rocks, near modern-day Bridgeport.

Besides being a visual landmark, Scotts Bluff was a physical obstacle to emigrants. The imposing bluffs blocked travelers from following directly along the banks of the North Platte River as they had done in earlier parts of the journey. Two historic paths passed through the bluffs. Gold rushers utilized the Robidoux Pass south of the river. First used in the 1820s and 1830s by fur traders, Robidoux Pass continued to serve travelers well into the 1850s. Once through the pass, travelers headed west toward Fort Laramie, Wyoming. About 1851, with the opening of Mitchell Pass, Robidoux Pass began to fall into disuse. Troops from Fort Laramie were perhaps the first to take wagons through Mitchell Pass, possibly engineering the pass to be wider and less steep, thus making it passable for wagon trains. Before long, most homesteaders used Mitchell Pass because it was a more direct route and had easier access to water. Established in 1864, Fort Mitchell was an important center of commerce for emigrants.

Events of the 1860s transformed Scotts Bluff and the West as a whole. Because of population growth and business concerns on the frontier, businessmen sought to ensure faster communication between the East and the West. The Pony Express was the first attempt at an efficient, transcontinental mail route, which began on April 3, 1860. The Pony Express delivered mail on horseback, with carriers riding from station to station. The operation only ran until October 1861, when the Pacific Telegraph, which went through Mitchell Pass, was completed. Although short-lived and a financial failure, the Pony Express demonstrated the feasibility of fast transcontinental communication. Located near Courthouse Rock, the Mud Springs Pony Express Station served as a stagecoach station and a telegraph station over the years and was a Pony Express station. The transcontinental railroad’s completion in 1867, when the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads met at Promontory Point, Utah, marked the end of widespread use of the Oregon Trail. Train travel was safer, more reliable, and quicker than travel by wagon.

Early in the 20th century, local and state interests devoted themselves to promoting Scotts Bluff as a symbol of the nation’s pioneering past. Scotts Bluff became a National Monument on December 12, 1919, following an intense lobbying effort. Despite the widespread public interest, the bluffs saw little change, save for foot trails and picnic areas, until the 1930s. At that time, government employment programs such as the Civil Works Administration (CWA), Works Progress Administration (WPA), and Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) began to construct Summit Road with its three tunnels and parking lot and State Highway 92, for many years the primary roadway to the site. They also built the Scotts Bluff National Monument Visitors Center and Museum, which now houses the world’s most extensive collection of original William Henry Jackson sketches, paintings, and photographs. Many are on display in the Visitor Center at Scotts Bluff.

In addition to visiting the museum, visitors can hike the Saddle Rock Trail, drive to the summit, and relive life on the Oregon Trail during the special Living History program on weekends during the summer.

Contact Information:

Scotts Bluff National Monument

PO Box 27

190276 Old Oregon Trail

Gering, Nebraska 69341

308-436-9700

Oregon Trail Memorial Cemetery near Scotts Bluff, Nebraska.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See:

Nebraska – The Cornhusker State

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West

Oregon Trail Through the Platte River Valley, Nebraska

William Henry Jackson – Recording the Old West

Primary Source: National Park Service