The American Revolution was an event of sweeping worldwide importance. A costly war that lasted from 1775 to 1783, it secured American independence and gave revolutionary reforms of government and society a chance to continue. At its core, the war pitted colonists who wanted independence and the creation of a republic against the power of the British crown, which wanted to keep its empire whole. At certain times and in certain places, Americans fought other Americans in what became a civil war. From the family whose farm was raided, through the merchant who could not trade, to the slave who entered British lines on the promise of freedom, everyone had a stake in the outcome.

1763-1774 – From Protest to Revolt

Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War ended her contest with France over North America but began a new conflict with her colonies. Many colonists questioned Britain’s decision to keep an army in postwar America, and almost all of them opposed Parliament’s effort to finance that army by taxing colonists. They petitioned against the 1764 Sugar Act, which imposed import duties, and the 1765 Stamp Act, which imposed direct taxes on selling playing cards, dice, newspapers, and various legal documents. Parliament could not tax them, the colonists insisted, because they had no representatives in the House of Commons, and British subjects could only be taxed with the consent of their elected representatives. When Parliament refused to back down, colonial mobs forced stamp distributors to resign. Direct action by interracial urban mobs was frequent in the Revolution’s lead-up. Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in March 1766 and passed a Declaratory Act affirming its complete authority over the colonists. The following year, it sought to raise revenue through new duties on glass, lead, paint, paper, and tea, known as the “Townshend Duties.” The colonists responded with a coordinated refusal to import British goods. British troops sent to Boston, Massachusetts, to enforce the duties only added to the tensions, leading to an incident between civilians and British troops on March 5, 1770, where British troops fired on an unruly mob, killing five people. Local radicals called it the “Boston Massacre.”

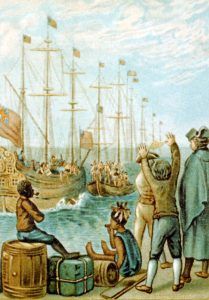

That same year, Parliament repealed all of the Townshend Cuties except that on tea. In 1773, Parliament reaffirmed the tax on tea and passed a Tea Act to help the British East India Company compete with smuggled tea. Colonists in some ports forced tea ships to return to Britain without unloading. That strategy failed in Boston, so a crowd thinly disguised as “Indians” dumped the imported tea into the harbor. Parliament responded to the “Boston Tea Party” with the Coercive Acts (called by the colonists the “Intolerable Acts”), which closed the port of Boston and changed the form of government in Massachusetts to enhance the Crown’s power. It then appointed General Thomas Gage commander of the British Army in America and governor of Massachusetts and placed that colony under military rule. In response, 12 colonies sent delegates to a Continental Congress that met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the fall of 1774 to coordinate support for Massachusetts’s “oppressed” people and opposition to the Coercive Acts. The Congress adopted a colonial bill of rights and petitioned Britain for a redress of grievances.

1775 – The War Begins

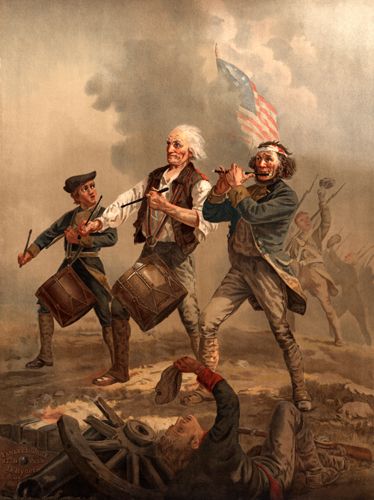

In late April 1775, General Gage sent British troops to seize colonial military supplies and arrest opposition leaders in the towns of Lexington and Concord, west of Boston, Massachusetts. The military clashes there and along the British retreat route began the Revolutionary War. News of the fighting spread quickly, and volunteer soldiers rushed to a provincial camp in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Soon, this force had the British army bottled up in Boston, a peninsula with just one narrow link to the mainland. Meanwhile, other colonial forces took the British forts at Ticonderoga and Crown Point in New York, seizing valuable military supplies. After assembling on May 10, 1775, the Second Continental Congress took charge of the makeshift Massachusetts force and appointed Virginian George Washington to command this “Continental Army.” In June, British troops frustrated an American attempt to fortify Breed’s Hill overlooking Boston but suffered heavy losses in the “Battle of Bunker Hill.” After that, General William Howe replaced Gage as commander of the British forces. In July, Washington arrived at Cambridge and began a rigorous program to discipline the American army. Late in August, Congress sent troops to take Canada, an operation that would take the rest of the year and end in disaster. But, as the year closed, American troops under Colonel Henry Knox began dragging 55 cannons from Ticonderoga to the siege at Boston.

1776-1777 – The War’s Early Stages

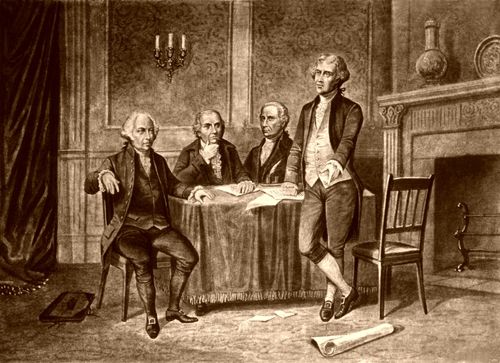

Leaders of the Continental Congress were John Adams, Gouverneur Morris, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Jefferson. By Augustus Tholey, 1894

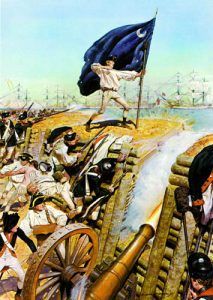

The year 1776 started badly for the colonists, who suffered a bitter defeat at Quebec, which dashed hopes of drawing Canadians into the conflict and opened the northern frontier to British attacks. In February, however, American supporters crushed loyalist forces at Moores Creek Bridge, North Carolina. In late March, the cannon from Ticonderoga allowed the Continental Army to force the British out of Boston. In June, American forces repulsed a British attack on Charleston, South Carolina. In June and July, the British began assembling one of the most significant naval and military forces ever seen in North America in New York.

Meanwhile, the Congress at Philadelphia approved the Declaration of Independence, which was read publicly to Washington’s troops in New York. After a costly defeat at Brooklyn Heights on Long Island, Washington crossed the East River back to Manhattan. He first retreated north, suffering defeats at Harlem Heights and White Plains, then down into New Jersey as the British captured Forts Washington and Lee on opposite sides of the Hudson River and took Manhattan Island. Washington finally crossed the Delaware River into Pennsylvania; after even he feared the cause was almost lost, he scored critical victories at Trenton, New Jersey, in late December and Princeton, New Jersey, in January, stopping the downward spiral. Soon, Washington’s army went into winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey.

In 1777, Britain tried to isolate radical New England from the other colonies by sending a force under General John Burgoyne down from Canada to the Hudson River. Troops under General Howe sailed from New York toward Philadelphia through the Chesapeake Bay. They captured Philadelphia, but Howe could not reinforce Burgoyne by then, who surrendered his much-diminished army to Continental soldiers and local militiamen at Saratoga, New York, in October. After that victory, the French negotiated an alliance with the Continental Congress, significantly reducing Britain’s chances of victory. Not only would French military and naval forces become available to the Americans, but Britain now faced a worldwide war and could no longer focus only on North America. Meanwhile, after being defeated by Howe’s forces at Brandywine and Germantown in Pennsylvania, Washington’s army went into winter quarters at Valley Forge, low on food and other necessities. There, German-born “Baron” Friedrich Wilhelm Augustus von Steuben drilled the troops, providing a discipline that would prove helpful the following year.

1778-1781 – The British Adopt a Southern Strategy

The year 1778 brought a significant change in British strategy. Britain had failed to subdue New England in the war’s first phase, and conventional warfare in the middle colonies had not reinstated the crown’s authority. Following France’s entry into the war, Britain concentrated on holding the southern colonies. It also made sporadic raids on northern ports and, with the help of Indian allies, on the frontier. Meanwhile, General Henry Clinton replaced General Howe as an overall British commander.

To counter the British activity in the West, which centered on their forts at Detroit and Niagara, George Rogers Clark, in the spring of 1778, assembled a force of about 200 men. Through forced marches, bold leadership, and shrewd diplomacy with Indian leaders, Clark captured the British posts of Cahokia and Kaskaskia in present-day Illinois on the Mississippi River. He then took Vincennes, Indiana, on the Wabash River. The British recaptured Vincennes but held it only briefly. Although he never captured the British stronghold at Detroit, Clark’s actions relieved much of the pressure on the frontier and were the first steps in breaking Britain’s hold on the Northwest Territory.

Believing the South to be home to many secret loyalists and hoping to keep the region’s timber and agricultural products for the Empire, the British sent an expedition that captured Savannah, Georgia, in December 1778. At first, the British concentrated on taking territory with regular army forces, then organized loyalist militia bands to hold the territory while the army moved on. This strategy largely succeeded in Georgia but broke down in the Carolinas. The British scored a significant victory with the capture of Charleston, South Carolina, and its 5,500 defenders in May 1780. Instead of discouraging patriot resistance, the fall of Charleston stirred it up and led to the formation of irregular militia bands to make hit-and-run attacks against the occupiers. The British had enough soldiers to move through the Carolinas and establish forts but not enough to protect their loyalist supporters or establish effective control. As soon as the British army moved on, loyalists were at the mercy of their pro-independence neighbors.

After General Clinton sailed for New York in June 1780, General Charles Earl Cornwallis took command of British forces in the South. He soon routed a patriot force under General Horatio Gates at Camden, South Carolina. Even the virtual elimination of a second American army just three months after their triumph at Charleston did the British little lasting good. Small militia bands under commanders like Francis Marion, Thomas Sumter, and Andrew Pickens continued to attack isolated British forces. In October, patriot militia from the Carolinas and Virginia defeated a loyalist army under British Colonel Patrick Ferguson at Kings Mountain, South Carolina, ending organized loyalist activity in the state and greatly boosting American hopes.

Following Kings Mountain, General Nathanael Greene arrived in North Carolina to reorganize the southern American forces. Soon after that, in January 1781, a combined force of Continental and militia troops under Daniel Morgan beat a British army at Cowpens, South Carolina. In March, Cornwallis and Greene tangled at Guilford Courthouse (present-day Greensboro), North Carolina. Cornwallis won a tactical victory, but one-quarter of his men were killed or wounded. After shifting to the coast at Wilmington, North Carolina, he decided to move his army north to Virginia. Greene then turned his attention to retaking South Carolina, capturing one by one the isolated British posts, including a 28-day siege that resulted in the British abandoning the town of Ninety-Six.

Cornwallis’s shift to Virginia resulted from frustration with the situation in the Carolinas and hoped that he could combine with General Clinton’s forces and win a decisive victory over Washington’s army. Washington was then encamped in New Jersey, engaged in planning for an attack on the British in New York in combination with the Comte de Rochambeau’s French army. A large French fleet under the Comte de Grasse had already left France with orders first to take control of the seas in the West Indies and then to support Washington and Rochambeau’s operations. In August, Washington learned that de Grasse was headed for the Chesapeake Bay and saw a chance to destroy Cornwallis before he could be reinforced. Leaving a small force to watch over New York City, Washington moved his remaining Continentals and the French troops toward Virginia.

Meanwhile, Cornwallis occupied and fortified Yorktown and Gloucester on opposite banks of the York River. A small Continental and militia force under the Marquis de Lafayette kept Cornwallis’s army occupied until Washington could concentrate his forces in Virginia. The British sent a fleet under Admiral Graves from New York to relieve Cornwallis, but the French fleet engaged it at the Naval Battle of the Capes. Graves returned to New York with his damaged fleet, leaving Cornwallis trapped at Yorktown. At the end of September, with heavy cannons landing under the protection of the French ships, the Allied forces began the siege of Yorktown. As the bombardment grew heavier and his attempt to break out from the Gloucester beachhead failed, Cornwallis had no choice but to order his subordinate Brigadier General Charles O’Hara to surrender his army of 8,000 to Washington on October 19, 1781.

End Game

Yorktown was a great victory for Franco-American arms, but it was inconclusive. The British still occupied New York City, Wilmington, Charleston, and Savannah, and there was no immediate prospect of the Americans taking these cities. However, the British were hard-pressed by years of war, and the government in London saw that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to replace Cornwallis’s army. The British public was also reaching the limits of its willingness to pay taxes to support the American war. Realizing that the costs of the war were more significant than the potential gain, the British government entered into peace negotiations, with Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay representing the United States. The Treaty of Paris, signed in September 1783, officially ended hostilities, recognized American independence, and made the Mississippi River the new nation’s western border. It also allowed Britain to retain Canada and return Florida to Spain. The failure of the British to withdraw from forts in the northwest with “all convenient speed” and difficulties with Spain over the navigation of the Mississippi River would require more negotiations. Still, American independence, virtually unthinkable in 1763, had been achieved.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Causes of the American Revolution

Initial Battles for Independence

Heroes and Patriots of America

Source: National Park Service