Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was the governing body by which the American colonial governments coordinated their resistance to British rule during the first two years of the American Revolution. The Congress balanced the different colonies’ interests and established itself as the official colonial liaison to Great Britain. As the war progressed, Congress became the effective national government of the country and, as such, conducted diplomacy on behalf of the new United States.

In 1774, the British Parliament passed a series of laws collectively known as the Intolerable Acts, intending to suppress unrest in colonial Boston, Massachusetts, by closing the port and placing it under martial law. In response, colonial protestors led by a group called the Sons of Liberty issued a call for a boycott. Merchant communities were reluctant to participate in such a boycott unless there were mutually agreed upon terms and a means to enforce the boycott’s provisions. Spurred by local pressure groups, colonial legislatures empowered delegates to attend a Continental Congress, which would set terms for a boycott. The colony of Connecticut was the first to respond.

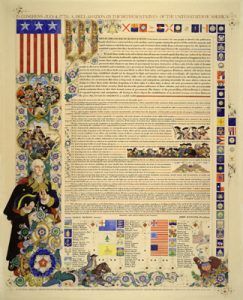

The Congress first met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on September 5, 1774, with delegates from the 13 colonies except for Georgia. On October 20, Congress adopted the Articles of Association, which stated that if the Intolerable Acts were not repealed by December 1, 1774, a boycott of British goods would begin in the colonies. The Articles also outlined plans for an export embargo if the Intolerable Acts were not repealed before September 10, 1775.

On October 21, the delegates approved separate statements for the people of Great Britain and the North American colonies, explaining the colonial position. On October 26, a similar address was approved for the people of Quebec.

Furthermore, on October 26, the delegates drafted a formal petition outlining the colonists’ grievances for British King George III. Many delegates were skeptical about changing the king’s attitude towards the colonies but believed every opportunity should be exhausted to de-escalate the conflict before taking more radical action. They did not draft such a letter to the British Parliament as the colonists viewed the Parliament as the aggressor behind the recent Intolerable Acts. Lastly, not fully expecting the standoff in Massachusetts to explode into full-scale war, Congress agreed to reconvene in Philadelphia on May 10, 1775.

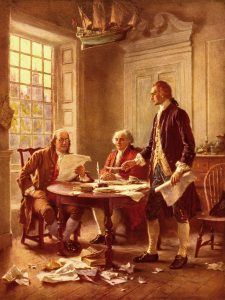

By the time Congress met again, war was already underway. Thus, the Second Continental Congress delegates formed the Continental Army and dispatched George Washington to Massachusetts as its commander. Meanwhile, Congress drafted the Olive Branch Petition, which attempted to suggest means of resolving disputes between the colonies and Great Britain. Congress sent the petition to King George III on July 8, but he refused to receive it.

As British authority crumbled in the colonies, the Continental Congress effectively took over as the de facto national government, exceeding the initial authority granted to it by the individual colonial governments. However, the local groups that had formed to enforce the colonial boycott continued to support the Congress. The Second Congress continued to meet until March 1, 1781, when the Articles of Confederation that established a new national government for the United States took effect.

The Continental Congress negotiated diplomatic agreements with foreign nations as the de facto national government. The British Parliament banned trade with the colonies and authorized the seizure of colonial vessels on December 23. These actions further eroded the positions of anti-independence moderates in Congress and bolstered those of pro-independence leaders. On April 6, 1776, Congress responded to Parliament’s actions by opening American ports to all foreign ships except British vessels. Reports from American agent Arthur Lee in London also served to support the revolutionary cause. Lee’s reports suggested that France was interested in assisting the colonies in their fight against Great Britain.

With a peaceful resolution increasingly unlikely in 1775, Congress began to explore other diplomatic channels and dispatched congressional delegate Silas Deane to France in April of 1776.

Deane succeeded in securing informal French support by May. By then, Congress was increasingly conducting international diplomacy and had drafted the Model Treaty with which it hoped to seek alliances with Spain and France. On July 4, 1776, Congress took the important step of formally declaring the colonies independence from Great Britain. In September, Congress adopted the Model Treaty and sent commissioners to France to negotiate a formal alliance. They entered into a formal alliance with France in 1778. Congress eventually sent diplomats to other European powers to encourage support for the American cause and to secure loans for the money-strapped war effort.

Congress and the British government made further attempts to reconcile. However, negotiations failed when Congress refused to revoke the Declaration of Independence in a meeting on September 11, 1776, with British Admiral Richard Howe and when a peace delegation from Parliament arrived in Philadelphia in 1778. Instead, Congress spelled out terms for peace on August 14, 1779, which demanded British withdrawal, American independence, and navigation rights on the Mississippi River. The next month Congress appointed John Adams to negotiate such terms with England, but British officials were evasive.

Formal peace negotiations would have to wait until after the Confederation Congress took over the reins of government on March 1, 1781, following American victories at Yorktown that resulted in British willingness to end the war.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023. Source: Office of the Historian

Also See: