The Pennsylvania Railroad Company, also known as the “Pennsy,” was an American Class I railroad established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named for the commonwealth in which it was established.

In the early 1840s, the commercial importance of Philadelphia was menaced from two directions. A steadily increasing trade volume passed through the Erie Canal from the Central West to the northern seaboard. At the same time, traffic over the new Baltimore and Ohio Railroad promised a tremendous commercial future to the rival city of Baltimore, Maryland. With commendable enterprise, the Baltimore and Ohio Company was even then reaching out for connections with Pittsburgh to divert western trade from eastern Pennsylvania. Moreover, Philadelphia’s financial prestige suffered from recent events. The panic of 1837, the contest of the United States Bank with President Andrew Jackson, its defeat and its subsequent failure as a state bank, and the consequent distress in local financial circles — all conspired to shift the monetary center of the country to New York.

At this time, Philadelphia capitalists began to arouse themselves to recover their lost opportunities. Philadelphia must share in this trade with the Central West. The Baltimore and Ohio Company designs needed to be defeated by bringing Pittsburgh into contact with its natural Eastern market. To this end, the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad was incorporated on April 13, 1846, with a franchise permitting the construction of a railroad across the state from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh. An added incentive to constructive expansion was given by an act of the Legislature authorizing the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to extend its line to Pittsburgh if the Pennsylvania Railroad Company failed to avail itself of its franchise.

To avoid the high cost of constructing a road between Philadelphia and Harrisburg, the Pennsylvania Railroad entered into arrangements with the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, which had opened in 1834 and was owned by the State — which ran through Chester and Lancaster to Columbia. This road was primitive and used both steam and horsepower. As late as 1842, a train was started only when sufficient traffic was waiting along the road to warrant engine use. Yet the road was famous in those days for the “rapidity and exceptional comforts of the train service.” Between Columbia and Harrisburg, westward-bound passengers had to use the Pennsylvania Railroad Canal.

Construction of the main line westward to Pittsburgh began at once and progressed rapidly. Using the Alleghany Portage Railroad from Hollidaysburg, the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad eventually secured a continuous line from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh. However, passengers were often inconvenienced when traveling between Philadelphia and Harrisburg for a long time. Finally, in 1857, the Pennsylvania Railroad bought the Philadelphia and Columbia from the State, rebuilt it, and extended it to Harrisburg. At the same time, the Pennsylvania Railroad bought the main line of the Public Works, which included the Alleghany Portage Railroad. On July 18, 1858, the first train passed over the entire line from Philadelphia via Mount Joy to Pittsburgh without transfer of passengers. At the same time, the first smoking car attached to a passenger train was used, and sleeping cars soon began to appear.

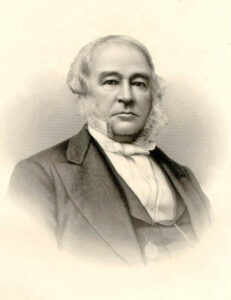

The railroad genius identified with the history of the Pennsylvania Railroad during the following decade is J. Edgar Thomson. A man of vision, great shrewdness, and ability, he was more like the modern railroad head of the Ripley or Underwood type than the Vanderbilt, Garrett, or Drew type. His interest was never in the stock market nor the speculative side of railroading but was concentrated entirely on the development and operation of the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad system. His dreams were not of millions quickly made nor of railroad dominance simply for the power that it gave; his mind was concentrated on the growth and prosperity of a vast railroad system which would increase with the years, become lucrative in its operations, and not only radiate throughout the State of Pennsylvania but extend far beyond into the growing West.

Under Thomson’s management, which lasted until 1874, the record of the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad was one of progress in every sense of the word. While Daniel Drew was lining his pockets with loot from the Erie Railroad and Commodore Vanderbilt was piling up his colossal fortune through consolidation and manipulation, J. Edgar Thomson was steadily building up the most significant business organization on the continent. In 1860, the entire Pennsylvania Railroad system was represented merely by the main line from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, with a few short branches. By 1869, the road had expanded within Pennsylvania alone to nearly one thousand miles and also controlled lines northward to the shores of Lake Erie through the State of New York.

However, the greatest accomplishment of the Thomson administration was the acquisition of the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne, and Chicago lines in 1869. This new addition gave the Company its own connection with Chicago, Illinois. It made a continuous system from the banks of the Delaware River at Philadelphia to the shores of Lake Michigan, thus rivaling the far-flung Vanderbilt line, a thousand miles long, which the industrious Commodore was now organizing. Shortly after, the Pennsylvania Railroad expanded on the east and obtained entry into New York City by acquiring the United Railroad and Canal Company, which owned lines across the State of New Jersey, passing through Trenton.

In the latter years of Thomson’s management, it became more and more evident that it was important for the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad to have further Western connections, which would reach the growing cities of the Middle West. While the Fort Wayne route made a straightforward connection with Chicago and included branches of value, the keen competition developing in the expansive years following the Civil War made actual control of the Middle Western territory a matter of sound business policy. The Vanderbilt lines reached out through Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois; the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad steadily developed Western connections. By then, Jay Gould had come actively on the scene with large projects for the Erie. To offset these projects, early in 1870, a “holding company” — probably the first of its kind on record — known as the Pennsylvania Railroad Company was formed for the express purpose of controlling and managing, in the interest of the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad, all lines leased or controlled or in the future to be acquired by the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad interests west of Pittsburgh and Erie. This Company took over the lease of the Fort Wayne route and acquired control by lease of the Erie and Pittsburgh, a road extending northward through Ohio to Lake Erie.

After this date, the expansion of the system west of Pittsburgh went on rapidly. In 1871, the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad, which had been opened as early as 1852, came under the Pennsylvania Railroad’s control. Soon after, many smaller lines in Ohio were merged into the system. The most important acquisition during this period, however, was the result of the purchase of the great lines extending westward from Pittsburgh to St. Louis, with branches reaching southward to Cincinnati and northward to Chicago. This system was then known as the “Pan Handle” route and later as the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis. It was a consolidation of several independent properties of importance that had been gradually extending over this territory during the previous decade. This new system, which embraced over 1400 miles of road, gave the Pennsylvania Railroad a second line to Chicago, a direct line to St. Louis, a second line to Cincinnati, and access to territory not previously tapped.

While the achievements of the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad Company during these years of consolidation and expansion were always at the forefront in matters of high standards and progressive practice, it pioneered most of the improvements later adopted by other roads. The Pennsylvania Railroad was the first American railroad to lay steel rails and the first to lay Bessemer rails; it was the first to put the steel firebox under the locomotive boiler; it was the first to use the air brake and the block signal system; and was the first to use the overhead crane in its shops.

In these earlier years, the Pennsylvania Railroad had established its enviable record for conservative and non-speculative management. No railroad wrecker or stock speculator had ever had anything to do with the company’s financial control, and this tradition was passed on from decade to decade. The railroad developed and established an equally clean record regarding its finances. The company began to pay a satisfactory dividend on its shares almost immediately and continued to do so right through the Civil War period. After the through line from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh was opened, the company consistently made dividend payments — a 60-year record that no other American railroad system duplicated.

The Pennsylvania Railroad continued to forge ahead even during the exciting period from 1877 to about 1889 when the trunk lines were aggressively carrying on that policy of cutthroat competition between Chicago and the Atlantic seaboard, which resulted in so severely weakening the credit and position of properties like the Baltimore and Ohio and the Erie. The Pennsylvania Railroad also indulged in rate cutting, but the management was equal to the situation and made up in other directions what it lost in lower rates. It gave superior service, developed a high operation efficiency, and steadily maintained its properties at a high standard. During these years, the president was George B. Roberts, who had succeeded Thomas A. Scott in 1880.

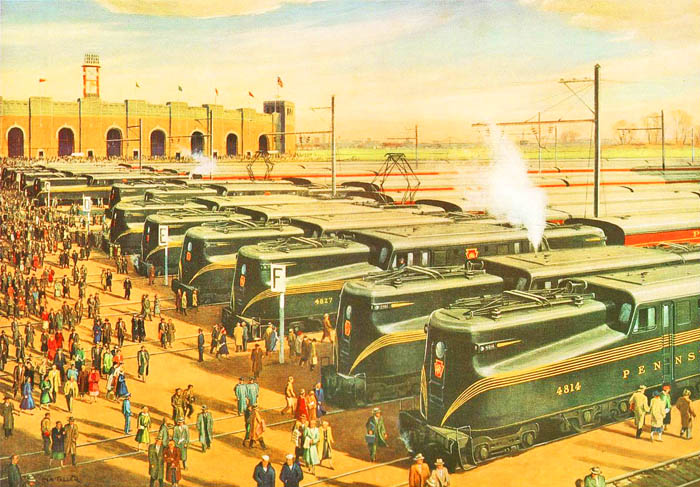

At its peak in 1882, the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad was the largest railroad by traffic and revenue, the largest transportation enterprise, and the largest corporation in the world.

Roberts’s management spanned the period from 1880 to 1897 and embraced a decade of comparative prosperity for the country and nearly a decade of panic and industrial and financial depression. During the earlier decade, the business of the Pennsylvania Railroad continually benefited from the industrial development and growth that marked the period. At this time, the Pittsburgh district became the great center of steel and iron manufacture. The discovery of petroleum in western Pennsylvania, creating an enormous new industry in itself, proved to be an event of far-reaching significance for the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad. The extensive opening up of the soft coal sections of western Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana also meant much for this great system of railroads.

Further developments in other directions accrued to benefit the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad. In this period, by obtaining control of a line to Washington, D.C., the system acquired a Southern artery running through Wilmington, Delaware, and Baltimore to Washington, D.C. Afterward, with other roads, the Pennsylvania Railroad acquired control of the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad and thus obtained a line to Richmond, Virginia. The expanding movement continued to the north and the east. In addition to developing its main line from Philadelphia to Jersey City, the Pennsylvania Railroad acquired many other New Jersey lines, including West Jersey and Seashore, a road from Camden to Atlantic City and Cape May.

During the aggressive administrations of Thomas A. Scott and George B. Roberts, the great system continued to spread out steadily until it had penetrated as far as Mackinaw City in the north and the Chesapeake Bay in the south. Its network of lines stretched across the continent’s Eastern section from New York to Iowa and Missouri. In contrast, the intensive development of shorter lines in the State of Pennsylvania and to the north was unceasing. The Northern Central Railroad ran south from Sodus Bay on Lake Ontario through central Pennsylvania to Baltimore, the Buffalo, and Alleghany Valley, extending from Oil City northward and joining the main system to the east, the Western New York and Pennsylvania operating north from Oil City to Buffalo and Rochester — these lines the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad acquired and consolidated in the Roberts regime.

After Roberts retired, Frank Thomson, a son of the earlier president of the same name, was placed at the head of the system for three years. But in 1899, Alexander J. Cassatt, who had been associated with the Pennsylvania Railroad as an officer, director, and stockholder for many years, took the helm, and a new chapter—probably the greatest in the history of this remarkable railroad—began.

The name Alexander J. Cassatt will always be linked with the comprehensive terminal developments in the region of New York City, which began almost immediately upon his accession to the presidency and were carried forward on bold and far-reaching lines. Perhaps more than any other person, Cassatt foresaw the approach of the day when New York City as a commercial center would outstrip all the other cities of the world both in the density of population and in the amount of wealth. He and his predecessors had for many years witnessed the tremendous industrial development of the Pittsburgh district, where property values had grown by leaps and bounds and where the steadily advancing development of industry and material resources had been so unmistakably reflected in the increasing earning power and value of the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad properties.

But while at Pittsburgh, the road had everything to favor it as far as terminals and rights of way through the heart of the great industrial district were concerned, in the great Eastern metropolis, the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad was at an obvious disadvantage, particularly as compared with the New York Central, which had its splendid terminal rights penetrating to the heart of the city. Cassatt saw that his company must, without delay, take several bold and, for the time, enormously expensive steps toward the development of terminal facilities in Greater New York or else forever abandon the idea of getting nearer the heart of the city than the New Jersey shore and thus run the risk, in the keen contest for commercial supremacy, of ultimately falling behind other more advantageously situated lines.

There were still further incentives for immediate action by the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad. While the New York Central was in an ideal position for handling all traffic destined for the New England States, the Pennsylvania Railroad could control practically none of this business, as its terminals were on the wrong side of the Hudson and necessitated not merely the inconvenient transfer of passengers but also the much more expensive handling of freight. Another disadvantage of the Pennsylvania Railroad was its inability to make the most economical terms for foreign shipping, as a large proportion of such freight had to be constantly transferred on lighters to the New York and Brooklyn sides of the harbor. Thus, any comprehensive plan for terminal development on the part of the Pennsylvania Railroad must include a tunnel system into New York City, an outlet through the city to Long Island, and a connection with the New England railroads.

The first move in developing this terminal system was the acquisition in 1900 of the control of the Long Island Railroad, embracing all the steam railway mileage on Long Island, with lines extending along both the north and south shores to Montauk Point. This acquisition added extensive freight yards and terminals on the Brooklyn side of the East River. The Company then obtained franchises and began the construction of its great tunnels under the North and East Rivers and entirely across New York City, with a mammoth passenger station at Seventh Avenue and Thirty-second Street. A great railroad bridge was planned to cross from Long Island to the mainland, connecting with the New York, New Haven, and Hartford systems, in the stock of which the Pennsylvania Railroad at this time purchased an interest.

The terminal construction took many years and cost over $100,000,000, besides the added costs involved in building up and developing the old, worn-out Long Island Railroad. It wasn’t until the 1900s that the project was rounded out and completed, with the final construction of the vital connection with the New England railroad systems. However, realizing this plan is undoubtedly the most significant achievement in the long career of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Had the project been delayed for another decade, it probably could not have been accomplished because of the growing expense of operation and the difficulties of getting franchise rights and rights of way through and under the metropolis.

While the tunnel development is the notable achievement of the Cassatt regime, this remarkable man’s name was closely identified with the “community of interest” idea. Cassatt aggressively pushed this “community of interest” scheme in cooperation with Harriman, Hill, and Morgan. Large stock purchases were made in the Norfolk and Western, the Chesapeake and Ohio, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroads. As the latter road had in its turn acquired, jointly with New York Central interests, a working control of the Reading Company, and the Reading Company had secured majority ownership of the New Jersey Central system, it is apparent that the domination which the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad had obtained over the entire Eastern seaboard south of New York City and north of Baltimore was made nearly complete.

The “community of interest” plan held sway with the country’s large railroads. It was very effective for perhaps half a dozen years until the interstate commerce laws were amended in such a way as to give the Government complete control over railroad freight and passenger rates. In 1906, the Pennsylvania Railroad began to dispose of the bulk of its holdings in competing properties, the most notable transactions being the sale of its entire interest in the Chesapeake and Ohio to independent interests and a substantial part of its Baltimore and Ohio holdings to the Union Pacific Railroad. A few years later, when the Union Pacific was forced by the Federal courts to dispose of its control of the Southern Pacific Company, a trade was made between the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Union Pacific whereby the latter took from the Pennsylvania Railroad the remainder of its Baltimore and Ohio investment and gave in exchange a portion of its large holding of Southern Pacific stock.

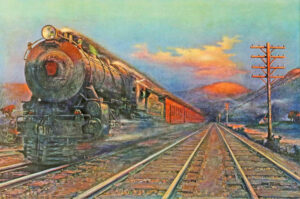

By 1920, the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad’s main line from New York to Pittsburgh traveled over the same ground that the road followed a generation or two before, along a four-track line stretching hundreds of miles between five, six, and eight tracks. Where mountains were once climbed, tunnels had been bored, where sharp curves were necessary, straight trackage was encountered. Grades were eliminated, and the whole route was modernized and strengthened by laying 100 to 150-pound rails.

Undoubtedly, the fortunate location of the Pennsylvania Railroad lines in the half-dozen States, which represented the financial and industrial heart of the continent, had much to do with its vast growth and expansion. Its high reputation was due to the long record of its superior methods and management. One of the primary objectives of the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad’s policy was to keep pace with the country’s growth. Instead of following in the wake of industrial progress and making improvements and extensions after its competitors had made theirs, its management usually had the foresight to prepare well in advance for future needs.

In the 1920s, the Pennsylvania Railroad carried nearly three times the traffic as other railroads of comparable length, such as the Union Pacific and Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroads. Its only formidable rival was the New York Central, which carried around three-quarters of the Pennsy’s ton-miles.

Over the years, it acquired, merged with, or owned part of at least 800 other rail lines and companies, and by the end of 1926, it operated 11,640.66 miles of rail line.

In 1968, the Pennsylvania Railroad Railroad merged with its rival New York Central Railroad, and the railroad eventually went by the name of Penn Central Transportation Company, or “Penn Central.” However, the former competitors’ networks integrated poorly with each other, and the railroad filed for bankruptcy within two years.

Bankruptcy continued, and on April 1, 1976, the Pennsylvania Railroad gave up its assets, along with the assets of several other failing northeastern railroads, to a new railroad named Consolidated Rail Corporation, or Conrail. Conrail was purchased and split up in 1999 between the Norfolk Southern Railway and CSX Transportation, with Norfolk Southern getting 58% of the system, including nearly all of the remaining former Pennsylvania Railroad trackage. Amtrak received the electrified segment of the Main Line east of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

After 1976, the railroad became an insurance company, which now goes by the name of American Premier Underwriters and is now a subsidiary of American Financial Group.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Primarily written by John Moody, author of The Railroad Builders, A Chronicle of the Welding of the States, published in 1919. Penetrating the Pacific Northwest is the seventh chapter of the book. However, it has been updated with additional information from Wikipedia.

Also See:

Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad