William Henry Jackson, a painter, photographer, and explorer, is known as the first person to photograph the wonders of Yellowstone and other places in the American West and to document the Civil War in several sketches.

Born in Keeseville, New York, on April 4, 1843, Jackson was the first of seven children born to George Hallock Jackson and Harriet Maria Allen. Harriet, a talented watercolorist, graduated from the Troy Female Academy, later the Emma Willard School. From an early age, young William picked up his mother’s passion, which was drawing and painting. At just ten years old, he received his first formal artistic training, learning to use perspective and form, color, and composition. His drawings now began to take on a more realistic and mature appearance.

His first job as an artist was not glamorous. In 1858, at just 13 years old, he was hired as a retoucher for a photographic studio in Troy, New York, where he worked for two years.

His job was to “warm up” black-and-white portraits by tinting them with watercolors and enhancing details in the photographs with India ink. During this time, he learned how to use cameras and the darkroom techniques of the time.

Things changed for the young man after the Civil War broke out, and in October 1862, at the age of 19, he joined as a private in Company K of the 12th Vermont Infantry of the Union Army. However, with the exception of occasional guard duty, there was little for him to do, and he spent his free time sketching drawings of his friends and various scenes of Army camp life that he sent home to his family as his way of letting them know he was safe. Luckily, his mother saved the pencil sketches created during his wartime service, and they survive today as a record of an infantryman’s life in the Union Army.

In June of 1863, Jackson’s regiment participated in the climactic Gettysburg campaign, but he never saw action in the battle. Instead, he was assigned to guard a supply train during the engagement. His regiment mustered out on July 14, 1863, and he returned to Rutland, Vermont. There, he found employment with a photographic studio with a good salary. A year later, he was engaged to a young woman from a prominent family. However, the couple broke up in 1866, and the heartbroken Jackson decided to leave Vermont and seek his fortune in the silver mines of Montana.

He soon set out with two friends to Nebraska City, Nebraska Territory, a jumping-off point for freighting caravans headed west. The three young men soon signed on as bullwhackers for a freight outfit bound for Montana. Despite knowing nothing about oxen or hauling freight, Jackson soon learned to handle the powerful draft animals.

Before long, Jackson was back to his old habits of sketching the things he saw and the people he met. Forsaking his dream of striking it rich, Jackson left the freight train near South Pass in Wyoming and headed south for Salt Lake City, Utah, and eventually California. His experiences in the West struck a chord in Jackson, and he began to realize that documenting the settling of the frontier might become his life’s work.

In 1867, he settled down in Omaha, Nebraska, along with his brother Edward Jackson. With his father’s assistance, he soon established his own photographic studio.

He began photographing American Indians from the nearby Omaha reservation and the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad.

On May 10, 1869, Jackson married Mollie Greer in Omaha. After a six-day honeymoon on a Missouri River steamboat, Jackson sent his new wife to live with her family in Ohio. He left for Cheyenne, Wyoming, on what Jackson considered his first “photographic campaign.” As his reputation grew rapidly, he was commissioned in late 1869 by E. & H. T. Anthony and Company to furnish them with 10,000 stereoviews of the American West, and he soon set up a satellite business in Wyoming.

In this capacity, he soon drew the attention of Dr. Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, who was organizing an expedition that would explore the geologic wonders along the Yellowstone River in Wyoming.

Hayden realized that a photographer would be useful in recording what they found. When offered the position, Jackson jumped at the opportunity.

His new wife, Mollie Greer Jackson, could run the business expertly while he was gone — in fact, she was much better at it than his brothers. Jackson caught up with the expedition in August 1870 at Camp Carlin, an Army supply depot outside Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Anyone else might have been daunted by the thought of transporting delicate camera equipment and glass plate negatives across the West. Still, Jackson’s experience as a bullwhacker would serve him well. The images he brought back caused a sensation. For many years, stories about geysers and waterfalls were considered tall tales, but Jackson provided proof of their existence. Public interest resulted in the U.S. Congress officially designating Yellowstone National Park in 1872, and Jackson’s name became a household word.

Survey responsibilities kept Jackson in the field each summer and demanded his presence in Washington during much of every offseason. This left so little time for Jackson to spend in Omaha, developing his business there, that they sold the Omaha studio when Mollie Jackson became pregnant in the fall of 1871. and Mollie to Washington, D.C., where she was closer to the survey’s headquarters. She died in childbirth a few months later.

Although Jackson never indicated his reaction to this tragedy, it appears that he redoubled his increased commitments to landscape photography and the Hayden Survey. In 1873, he married Emilie Painter, the daughter of Dr. Edward Painter, an Indian agent for the Omaha tribe. Like Mollie Greer, Emilie Painter had a strong character and an independent streak; she not only thrived in her partnership with her photographer husband but enjoyed a social and creative life of her own.

For seven years, Jackson worked with Dr. Hayden for the United States Geological Survey, which took him to several unique and unexplored places, such as Mesa Verde, Colorado, and Yosemite, California, which Jackson documented with thousands of photographs.

His most famous image would be taken on August 24, 1873. For years, stories of a mountain with a large cross etched in its side had been circulating, but it wasn’t until Jackson risked climbing Colorado’s western slope of the Rocky Mountains that its existence was proven.

Within a few months of the photograph’s publication, his image of the Mount of the Holy Cross adorned the parlors in thousands of American homes. Jackson’s work for the United States Geological Survey ended in 1878. He continued to work in the West, opening a studio in Denver, Colorado, returning to portrait photography, and documenting railroad construction in mining towns in the Rockies.

From 1890 to 1892, Jackson produced photographs for several railroad lines, including the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and the New York Central Railroad. In 1893, many of Jackson’s photographs were used by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in their exhibit at the World’s Columbian Exposition.

From 1894 to 1896, Jackson was a member and photographer for the World’s Transportation Commission, organized by Joseph Gladding Pangborn, a publisher for the Railroad. Jackson produced more than 900 photographs for the commission.

During the Panic and Depression of 1893-95, Jackson accepted a commission by Marshall Field to travel the world photographing and gathering specimens for a vast new museum in Chicago.

In 1897, he became a partner in the Detroit Photographic Co., which at the time had exclusive rights to the photochrom process for the American market. This process allowed color enhancement of black-and-white photography. He joined the company in 1898 as a part-owner. His estimated 10,000 negatives provided the core of the company’s photographic archives, from which they produced pictures, postcards, and large-plate panoramas. In 1905, the company changed its name to the Detroit Publishing Co.

In about 1910, the company expanded its inventory to include photographic copies of works of art. At its height, it drew upon 40,000 negatives for its publishing effort and had sales of seven million prints annually. At this time, it also employed about 40 artists and more than a dozen traveling salesmen.

However, during World War I, competing firms developed new and cheaper printing methods, and the company began to decline. In 1924, it went into receivership, and eight years later, in 1932, its assets were liquidated.

The year the Detroit Publishing Co. failed – 1924, Jackson moved to Washington, D.C., laid down his camera, and picked up a paintbrush. Though he was 81, he began to produce murals of the Old West for the new U.S. Department of the Interior building. His eye for composition, coupled with the fact that he had experienced the transformation of the West firsthand, gave added credibility to his work.

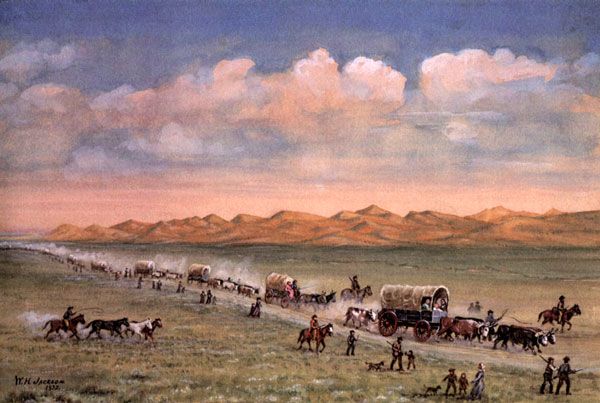

Soon, his paintings of Western scenes were in demand for illustration in books and articles. Jackson completed approximately 100 paintings, mostly dealing with historical themes such as the Fur Trade, the California Gold Rush, and the Oregon Trail.

During this time, he revisited many of the sites he depicted in his paintings to paint them as accurately as possible. For those scenes that predated his own lifetime, he sought out and interviewed surviving participants.

In 1936, Edsel Ford, backed by his father Henry Ford, bought Jackson’s 40,000 negatives from the estate of William A. Livingstone, who had owned the Detroit Publishing Co. The negatives were purchased for The Edison Institute, now known as Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan. Eventually, Jackson’s negatives were divided between the Colorado Historical Society and the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

On June 30, 1942, William Henry Jackson died at the age of 99 at a New York City hospital from complications and injuries received from a fall. He left one son, two daughters, seven grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren. Recognized as one of the last surviving Civil War veterans, he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. His long and active life paralleled the formative years of Westward Expansion in the United States, and his many contributions as a soldier, bullwhacker, photographer, explorer, publisher, author, artist, and historian have left a lasting legacy on the nation.

Today, Scotts Bluff National Monument in Nebraska houses the world’s largest collection of original William Henry Jackson sketches, paintings, and photographs. Many are on display in the Visitor Center at Scotts Bluff.

Oregon Trail pioneers pass through the sand hills, painting by William Henry Jackson

Compiled/Edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See:

Detroit Publishing Co. – America In Color

Historic Photographers of America’s History

William Jackson and the Detroit Publishing Co. Photo Gallery

Primary Source: National Park Service