The Mexican-American War, from its outbreak on May 13, 1846, until the termination of hostilities signified by the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848, transformed the Santa Fe Trail. United States’ acquisition of the Southwest following the conflict put the Trail under domestic jurisdiction, although it still carried international trade.

Mexico had always viewed Texas and the United States as different entities, but the passage of a joint resolution for the annexation of the Republic of Texas through U.S. Congress on March 1, 1845, placed considerable stress on U.S. relations with Mexico. Other factors in previous years such as the U.S. territorial expansion of the 1840s, the migration of U.S. citizens into northern Mexico via the Santa Fe Trail, the boundary dispute between Texas and Mexico, U.S. citizens’ financial claims against Mexico in addition to the political instability of the Mexican government, all contributed to a weakening of relations between the two countries. The election of James K. Polk as President of the United States in 1844 under a mandate for Manifest Destiny announced the U.S. intention to expand to the Pacific Ocean with Oregon, Texas, and California just three of the goals of the expansionist movement. Official hostilities between the United States and Mexico began on May 13, 1846, when the U.S. Congress declared war on Mexico.

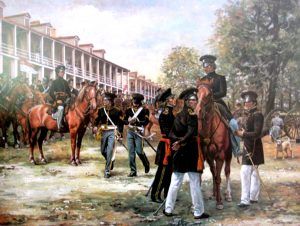

The Santa Fe Trail contributed to the expansion of the Union. Among the first U.S. forces to move along the Santa Fe Trail into New Mexico was the Army of the West under the command of Colonel Stephen Watts Kearney. The Army of the West left Fort Leavenworth, Kansas on June 16, 1846, and chose to follow the Mountain Route of the Trail because it provided access to water and to a ready-made base for operations — Bent’s Fort, Colorado. From Bent’s Fort, on August 2, 1846, the Army of the West marched toward Santa Fe, New Mexico, reaching the city unchallenged on August 18, 1846. The first wagon train to succeed Kearny’s army was that containing Susan Shelby Magoffin by whose account it took five days to cross Raton Pass. Kearney was anxious to promote his mission as one of liberation and not that of conquest, so, to this end, circulars were sent to Mexican villages in advance, promising them friendship and protection under U.S. control. Brigadier General Kearney declared the U.S. occupation of New Mexico on August 19, 1846. The annexation of New Mexico by the United States resulted in Charles Bent being installed as Governor of the territory of New Mexico on August 22, 1846.

As the territory of the United States increased, so too did the need for more routes farther west. The Mormon Battalion, composed of 500 young men from Nauvoo, Illinois, under the leadership of Captain Philip St. George Cooke, were dispatched from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to provide support for the Army of the West as it set out to open a wagon road from the Rio Grande to California. The Mormon Battalion followed the Cimarron Route and met with some resistance in New Mexico in 1847. Reinforcements were sent via the Santa Fe Trail under the leadership of Colonel Sterling Price, and they were successful in maintaining U.S. control. Another portion of the Army of the West under the command of Colonel Alexander Doniphan marched down the Rio Grande Valley to capture Chihuahua, Mexico, which had also become a popular destination for Santa Fe traders.

Troops assigned to occupy New Mexico were dispatched over the Santa Fe Trail at various times during the course of the Mexican War. Indeed, many individuals who had become familiar with the Trail through their part in the war effort would later come back as traders. Resistance to U .S. occupation continued in the form of guerrilla warfare with insurrections at Taos and Mora, New Mexico, in early 1847, with Governor Charles Bent perishing in the Taos confrontation. The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848 signaled the end of the war, but only the beginning of expanding trade. Three thousand wagons, 12,000 people, and 50,000 head of livestock were estimated to have moved over the Trail in the summer of 1848.

Increasing use of the Santa Fe Trail during the Mexican War continued to pose a threat to American Indian habitation. Big Timbers, located east of Bent’s Old Fort on the Arkansas River in Colorado, is an example of one such instance. At Big Timbers between 1846 and 1847, the increase in traffic along the Santa Fe Trail meant that the habitat and hunting of game had been disrupted, the water had been polluted, and trees had been cut down indiscriminately.

As a result of such incursions, 47 Trail travelers were killed, 330 wagons were destroyed, and 6,500 animals were stolen. In September 1847, a battalion of troops was assigned to guard the wagon trains. Roving columns of soldiers ready to participate in battle were employed initially; however, this mobile police force proved to be ineffective due to the length of the corridor that had to be patrolled.

With the signing of the treaty, the United States acquired what is now considered New Mexico, Arizona, California, Nevada, and Utah, in addition to parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas. The Texas Annexation of 1845 and the Mexican Cession of 1848 provided for the creation of California, the Utah Territory, New Mexico Territory, and Texas, with the remainder comprising the unorganized territory. Despite the U.S. preparation for war with Mexico, several aspects of the execution of a successful military operation, as they related to the Santa Fe Trail, were apparently not fully considered. The method of supplying the army demonstrated a lack of deliberation in that provisions reached the military outposts faster than wagons could become available for their distribution. Even when they were available, their drivers were often inexperienced.” The Mexican War altered the pattern of the Old Santa Fe trade. New Mexican and interior Mexican merchants, while successful, assumed a declining proportion of the Santa Fe trade following the Mexican War. The Santa Fe route changed from foreign to domestic jurisdiction while small proprietors were replaced by large freighting companies. With the increasing commercial value of merchandise, the Santa Fe trade expanded.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Santa Fe Trail (main page)