By Richard W. Stewart

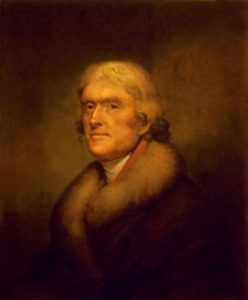

Not long after Thomas Jefferson became President, rumors reached America that France had acquired Louisiana from Spain. The news was upsetting. Many Americans, including Jefferson, believed that when Spain lost its weak hold on the colonies, the United States would automatically fall heir to them. But, with a strong power like France in possession, it was useless to wait for the colonies to fall into the United States’ lap like ripe fruit.

The continued presence of France in North America also raised a new security problem. Until then, the frontier defense problem had been chiefly pacifying the Indians, keeping the western territories from breaking away, and preventing American settlers from molesting the Spanish. Now, with a strong, aggressive France as a backdoor neighbor, the frontier problem became tied up with the question of security against possible foreign threats. The transfer of Louisiana to France also marked the beginning of restraints on American trade down the Mississippi River. In the past, Spain had permitted American settlers to send their goods down the river and deposit them at New Orleans. Before transferring the colony, however, Spain revoked the American right of deposit, which made it almost impossible for Americans to send goods out by this route.

The Louisiana Purchase

These considerations persuaded Jefferson in 1803 to inquire about the possibility of purchasing New Orleans from France. When Napoleon, anticipating the renewal of the war in Europe, offered to sell the whole of Louisiana for $15 million, Jefferson quickly accepted and suddenly doubled the size of the United States. After taking formal possession of Louisiana on December 20, 1803, the Army established small garrisons at New Orleans and the other former Spanish posts on the lower Mississippi River. Jefferson later appointed Brigadier General James Wilkinson, who had survived the Army’s various reorganizations to become a senior officer, as the new territory’s first governor.

Six months before the Louisiana Purchase, President Jefferson had persuaded Congress to explore the unknown territory west of the Mississippi River. The acquisition of the Louisiana Territory now made such an exploration even more desirable. It was no accident that the new nation and its president turned to the Army for this most important mission. Soldiers possessed the toughness, teamwork, discipline, and training appropriate to the rigors they would face. The Army also had a nationwide organization, even in 1803, and thus the potential to provide requisite operational and logistical support. It was perhaps the only truly national institution in America other than Congress.

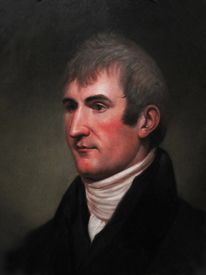

To lead the expedition, Jefferson chose Captain Meriwether Lewis, a 28-year-old infantry officer who combined the necessary leadership ability and woodland skills with the potential to be an observer of natural phenomena. Lewis, in turn, received the President’s permission to select William Clark as his co-captain. A former infantry company commander, Clark was a superb leader of men and an expert woodsman.

Both men had served under General Anthony Wayne along the western frontier. Of the 48 men who accompanied Lewis and Clark up the Missouri River to the Mandan villages in 1804, 34 were soldiers, and 12 were contract boatmen. The two other men were York, Clark’s manservant, and George Drouillard, the contract interpreter. Of the 31 individuals who made the trip with Lewis and Clark to the Pacific coast in 1805 and back in 1806, 26 were soldiers. The other five were York, Drouillard, and the Charbonneau family (Toussaint, Sacagawea, and their newborn son, Jean Baptiste).

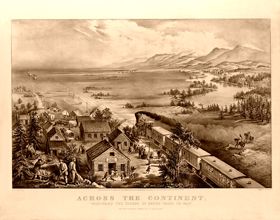

From the summer of 1803 to the fall of 1806, the expedition was an Army endeavor, officially the “Corps of Volunteers for North Western Discovery.” It led Americans across the breadth of the vast continent for the first time. Its scientific agenda brought back invaluable information about flora, fauna, hydrology, and geography. Its benign intent resulted in peaceful commerce with Indians encountered en route. All things considered, the expedition was a significant example of America’s potential for progress and creative good.

While Lewis and Clark were exploring beyond the Missouri River, General James Wilkinson sent Captain Zebulon M. Pike on a similar expedition to the headwaters of the Mississippi River. In 1807 Wilkinson organized another expedition. This time he sent twenty men under Captain Pike westward into what is now Colorado. After exploring the region around the peak that bears his name, Pike encountered some Spaniards who, resentful of the incursion, placed his party under armed guard and escorted it to Santa Fe, New Mexico. The Spanish took the Americans into Mexico and back across Texas to Natchitoches, once more in American territory. Despite the adversity, the Lewis and Clark Expedition and Captain Pike contributed much to the country’s geographic and scientific knowledge and remain great epics of the West.

To march across the continent might seem the manifest destiny of the republic, but it met with an understandable reaction from the Spanish. The dispute over the boundary between Louisiana and Spain’s frontier provinces became a burning issue during Jefferson’s second administration. Tension mounted in 1806 as rumors reached Washington of the dispatch of thousands of Spanish regulars to reinforce the mounted Mexican militiamen in east Texas. Jefferson reacted to the rumors by calling up the Orleans and Mississippi Territories’ militia and sending about 1,000 regulars to General Wilkinson to counter the Spanish move. The rumors proved unfounded; the Spanish outnumbered the American forces in the area at no time. A series of cavalry skirmishes occurred along the Sabine River, but the opposing commanders prudently avoided war by establishing a neutral zone between the Arroyo Hondo and the Sabine River. The two armies remained along this line throughout 1806, and the neutral zone was a de facto boundary until 1812.

By Richard W. Stewart; American Military History, Volume I, Center of Military History, 2009. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Corps of Discovery – The Lewis & Clark Expedition