Located at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers at the southernmost tip of Illinois is the town of Cairo, pronounced “Care-O.” By far one of the strangest and saddest cities I’ve ever visited, I was immediately intrigued by the empty streets and abandoned and crumbling buildings.

On our first visit in 2010, we passed under an arch depicting “Historic Downtown Cairo” to peek at this city that has been standing on the river for more than 150 years. Though the town had a population of some 2,800 people and is the county seat of Alexander County, its Main Street, called Commercial Avenue, was empty of people and lined with buildings in various stages of decay. Doors stood wide open on commercial buildings that displayed rubble-filled interiors, windows were broken or boarded up, Kudzu crawled up brick walls, street signs were faded and rusty, and the streets and sidewalks were cracked and choked with weeds. On a side street, the once lovely Gem Theatre stood silently beside the Chamber of Commerce. In other parts of the city, the large brick hospital was overgrown with vegetation, churches were boarded up, and restored mansions sat next to abandoned and crumbling large homes.

What has happened here? With Commercial Avenue’s proximity to the Ohio River, I was sure the town had been devastated by a flood, but I didn’t know and found no one to ask. Finally, after wandering about the deserted buildings for a time, an elderly gentleman parked his truck and walked out along the river, so I stopped and asked him. He told a brief story of how the town was destroyed by its own residents and pointed out a building that once served as a fine dining and dancing establishment that he and his wife enjoyed decades ago.

When I returned home to research, I discovered that Cairo died because of racism.

The peninsula where Cairo now stands was first visited by Father Louis Hennepin, a French explorer and missionary priest, in March 1660. It was noted again by other traveling priests over the next few years. Still, it would not be settled until 1702 when French pioneer Charles Juchereau de St. Denys and a party of about 30 men built a fort and tannery a few miles north of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers confluence. The party of men was highly successful in collecting thousands of skins for shipment back to France. However, the following year, the fort was attacked by Cherokee Indians, who killed most of the men and seized the furs, effectively ending the life of the fort and tannery.

Cairo, Illinois, at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.

Nearly a century and a half later, Lewis and Clark left Fort Massac, Illinois, and arrived near what would later become Cairo in November 1803. They worked jointly on their first scientific research and description to study geography at the junction of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. On November 16, they began the diplomatic phase of their journey when they visited the Wilson City area of Mississippi County, Missouri, and met with Delaware and Shawnee Indian chiefs. They ended their surveys at Cairo on November 19 and proceeded up the Mississippi River, now working against the current.

The first attempt at settlement occurred in 1818 when John G. Comegys of Baltimore, Maryland, obtained a charter to incorporate the city and the Bank of Cairo from the Territorial Legislature. He bought 1,800 acres on the peninsula and named it “Cairo” because it was presumed to resemble that of Cairo, Egypt. Working with Comegys was Shadrach Bond, the first governor of Illinois. These men and other speculators invested and tried to develop Cairo into one of the nation’s great cities.

The peninsula’s land was to be divided into lots and sold, with a portion of the money going toward improvements and the rest for capitalizing the new bank. The peninsula was surveyed, and the city was platted. However, when Comegys died in 1820, his plan died with him. However, he left behind a contribution in his choice of the name Cairo, and as a result, “Egypt” became the popular nickname for southern Illinois.

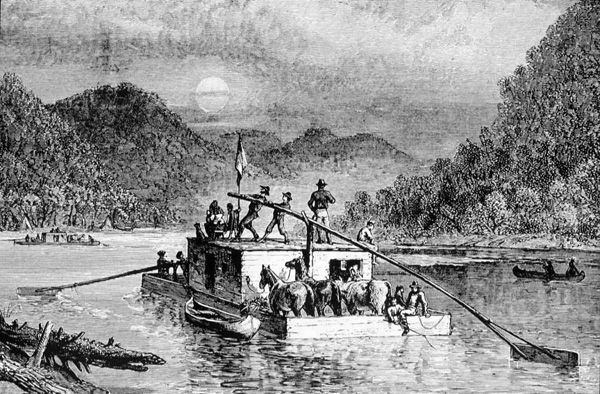

Flatboat on the Ohio River

A second and successful attempt at settlement began in 1837 when the Illinois State Legislature incorporated the Cairo City and Canal Company, with Darius B. Holbrook, a shrewd businessman from Boston, Massachusetts, as president. Holbrook soon hired several hundred workmen who constructed levees, a dry dock, a shipyard, sawmills, an ironworks, a large two-story frame hotel, a warehouse, and several residential cottages. A store was kept in a boat.

The city’s future looked promising as work on the Central Illinois Railroad brought many people to Cairo. In the meantime, several farms were established, and area villages in the county flourished.

The settlement was widely advertised in England, where the Cairo City and Canal Company bonds found eager purchasers through the London firm of John Wright & Company. However, when the London firm failed in November 1840, the fledgling town of Cairo immediately declined, dropping in population from 1,000 to less than 200 within two years. Those who remained operated shops and taverns for steamboat travelers. The census of 1845 showed 113 people in 24 families.

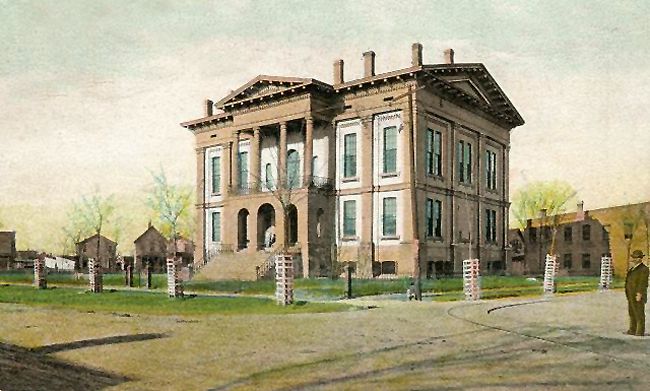

Alexander County Courthouse was built in Cairo, Illinois, in 1865.

For more than a decade, the “town” languished, but in 1853, the company began to sell lots in anticipation of the railroad arriving in the area. The town began to grow when the Illinois Central Railroad was completed in 1856, which connected Cairo to Galena, Illinois, in the northwest corner of the state.

At that time, expectations were still high when Cairo was predicted to surpass St. Louis, Missouri; Louisville, Kentucky; and Cincinnati, Ohio, as an urban center. Some even recommended that the city become the United States’ capital. Of course, despite these boasts, the city did not prosper to such an extent.

In 1858, the town was incorporated, and two years later, its population exceeded 2,000. It quickly became a vital steamboat port as goods and supplies were moved further south to New Orleans. In 1859, the city shipped six million pounds of cotton and wool, 7,000 barrels of molasses, and 15,000 casks of sugar. In 1860, Cairo became the county seat of Alexander County. An elegant courthouse was built in 1865 and stood until the 1960s when it was torn down and replaced with a new one.

The old Illinois Central Railroad storage bins near the Ohio River were used as hiding places for slaves traveling the Underground Railroad through Cairo.

Before the Civil War, the city also became an important transfer station on the Underground Railroad. After the Illinois Central Railroad was completed, fugitives were shipped north on the river before being transferred to railroad lines headed toward Chicago.

More than a century and a half later, In June 1998, Cairo city workers discovered what appeared to be storage bins under the sidewalk along the 600 block of Levee Street. The Illinois Central Railroad originally ran down the street, and the structures date back to the late 1850s. Physical evidence suggests that the rooms and an adjoining tunnel ran for five or six blocks along the street and were utilized to hide and move fugitive slaves.

In 1858, the grandest hotel in the city was built at the southwest corner of 2nd and Ohio Streets. The St. Charles Hotel opened in January 1859. During the Civil War, it would, at different times, become the headquarters of General Ulysses S. Grant and General John A. McLernand and filled to total capacity. Later, in 1880, the business was purchased by the Halliday Brothers, who vastly improved it and renamed it the Halliday Hotel. For decades, it was known as the best hotel in the city. Unfortunately, it burned to the ground in 1942.

By 1861, when the Civil War began, Cairo’s population had increased to 2,200, of which only 55 people were African-American. The port quickly became a strategically important supply base and training center for the Union army. For several months, both General Ulysses S. Grant and Admiral Andrew Foote had headquarters in the town. Several federal regiments were also stationed there during these turbulent years.

The Confederacy also realized its strategic importance. Knowing this, Illinois Governor Richard Yates immediately shipped 2,700 men with 15 pieces of field artillery, plus several six-pounders and one twelve-pound cannon, to Cairo from Springfield. More troops were stationed nearby, and by June 1861, 12,000 Union soldiers were in and around Cairo. Another 38,000 men were stationed within a 24-hour ride.

To further strengthen Cairo as a military camp and naval base, Yates sent more artillery to the city in the fall of 1861, including 7,000 new guns, 6,000 rifled muskets, 500 rifles, and 14 artillery batteries. The soldiers then built 15-foot-high levees around the city, making it a formidable installation.

At the very tip of the peninsula, south of Cairo, Camp Defiance was established near the river bank, and Camp Smith was located just a short distance to the north. Camp Defiance was first called Fort Prentiss after Union officer Benjamin Mayberry Prentiss, who had served honorably in the Mexican-American War.

Initially, the post consisted of a flat-topped mound upon which three 24-pound cannons and an 8-inch mortar were placed. The site also included a command house and a ship’s mast for the colors. The name was later changed to Camp Defiance when General Ulysses S. Grant arrived.

Lines of sentries were posted along the levees, and all boats along the river were stopped and searched. Camp Defiance became a vital supply depot for General Grant’s Western Army and a naval base as the Union and Confederacy battled for control of the lower Mississippi River. The Union shipped supplies from Chicago to the far tip of Illinois via the Illinois Central Railroad, fueling Grant’s push deep into the Confederacy and altering the course of the Civil War.

The city became an enormous military camp with a vast parade ground and clusters of barracks on all sides. The fortified city quickly gained the entire country’s attention, drawing many reporters to observe the military build-up and spurring The New York Times to call Cairo “the Gibraltar of the West.”

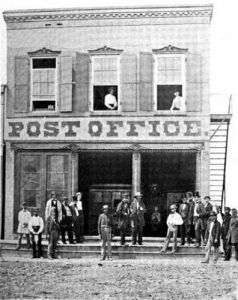

Generals Ulysses S. Grant and John A. McLernand stood on the steps in the center of Cairo’s post office in 1861.

But, the troops who were stationed in Cairo did not like the location. Despite the levees, the low, flat land was extremely muddy, and the town was prone to flooding. The climate was humid, disease-carrying mosquitoes and rats were everywhere, and to make matters worse, unscrupulous business operators were known to cheat and even rob many of the troops. One soldier described Cairo this way:

“I have witnessed hog pens that are palaces compared with our situation here.” Anthony Trollope, a renowned English novelist, visited the city in 1862 and wrote: “The inhabitants seemed to revel in dirt… the sheds of soldiers… bad, comfortless, damp and cold.”

During the Civil War, several businesses were established for soldiers and citizens, including stables, a hospital, and a wheelwright shop. Along the west side of the Ohio River, several saloons and brothels sprang up that served the military personnel until they were closed down by General John A. McLernand in October 1861. Just to the West, on Commercial Avenue, sat the firms of Koehler’s Gunshop, a drug store, the city’s post office, the famous Athenaeum Theater, a blacksmith, and a harness shop. A block South of this site was the vast parade grounds.

Though the fortified city never saw any attacks during the Civil War, it trained and shipped thousands of soldiers who would fight in numerous battles. Cairo’s real “war” would not begin for another century.

Camp Defiance and most military buildings were dismantled when the Civil War was over. Many years later, the site of Camp Defiance would become Fort Defiance Park, an Illinois State Park. However, today, the park is owned by the city of Cairo. Unfortunately, it is abandoned, overgrown, and entirely run down.

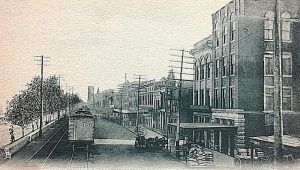

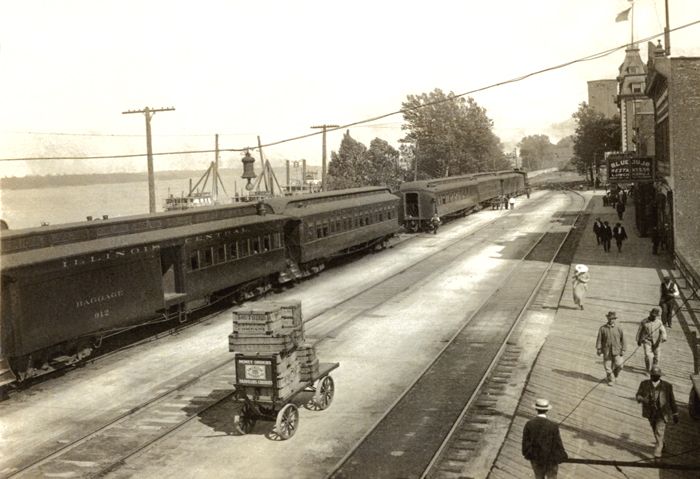

Cairo, Illinois, in 1861.

The Civil War dramatically changed the city’s social, cultural, and demographic landscape with the arrival of thousands of runaway slaves, which the government referred to as “contrabands.” Additionally, in 1862, the Union Army deposited large numbers of African-Americans in Cairo until government officials could decide their fate. These many black men, women, and children lived in a “Contraband Camp” established by the Army. The camp was later abandoned when the African Americans found little work and having no money to buy farms, many returned to the South and became sharecroppers.

When the war ended, the city became a staging area for many freed slaves arriving from the South. Many of these people also returned to the South or moved elsewhere, but more than 3,000 decided to remain in Cairo. The decidedly Southern influence of most white residents and the large influx of African Americans would spawn racial tension lasting over a century. During the next two decades, Cairo’s African Americans banded together to form a new society with their own institutions and culture, especially as they faced prejudice and hatred from white citizens.

Cairo Customs House, now a museum, houses one of Illinois’s most significant volunteer-driven museum collections. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

In the meantime, Cairo continued to grow due to the high river traffic. There was so much river traffic that the Federal Government designated Cairo as a Port of Delivery and began planning to build a United States Customs House. The building was designed by Alfred Mullett, who also designed the San Francisco Mint, the U.S. Treasury Building, and the old State Department building in Washington, D.C.

Opened in 1872, the building also held a U.S. Post Office on the first floor, which became third in importance in the nation because of its mail connections to and from the emerging West. The second floor housed various government agencies, and a Federal courtroom was on the third floor. Called the “Old Customs House” today, it continues to stand as a museum and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is located at 1400 Washington Avenue.

Also completed in 1872 was Magnolia Manor, built by Cairo businessman Charles A. Galigher, beginning in 1869. Galigher was a prosperous early miller who owned Chas Galigher & Co., Cairo City Mills, and an extensive ice factory before the Civil War began in 1861. He was also a personal friend of General Ulysses S. Grant and supplied the Union Army with flour and hardtack during the war.

The Victorian house is an ornate example of the prosperity of the era during which it was constructed. The 14-room home was built using locally fired red brick with substantial wood trim and stone. Ornamental cast iron decorates the verandas, and the ornate exterior cornice and eaves brackets are of wood millwork. After the house was completed, it was widely admired for its architecture and setting. The walls were made of double brick, with a ten-inch air space between them to keep out the dampness. A high, white fence enclosed the original grounds and planted many magnolia trees.

The Magnolia Manor in Cairo, Illinois, was built by the Cairo businessman Charles A. Galigher. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

The mansion became an outstanding social center during the 1870s and reached the peak of its fame on April 16, 1880, when ex-President and Mrs. Grant were guests for two days following their world tour. In the years following this visit, the Galighers and later owners continued to welcome guests into the big mansion among the magnolias.

The Cairo Historical Association acquired the house in 1952 and now operates it as a museum at 2700 Washington Avenue. In December 1969, the mansion was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Another large 19th-century home, Riverlore, built by Captain William P. Halliday, is located across the street from Magnolia Manor. It features a Greek theatre complete with pillars. This mansion, also listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is now owned by the City of Cairo and is open for tours.

This entire residential neighborhood is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is filled with imposing mansions along the magnolia-shaded streets that testify to Cairo’s heydays as a Mississippi River port. Washington Avenue, where many of these historic homes are situated, has long been called “Millionaire’s Row.”

Cairo’s economy continued to develop in other ways – primarily manufacturing. Many businesses, attracted by Cairo’s convenient geographic location, abundant natural resources, and good labor pool, established small-scale industries, some of which included barrel factories, breweries, grain mills, lumber mills, a cottonseed oil manufacturer, pottery plants, brickyards, tool manufacturers, and a Singer Sewing Machine plant.

During this time of growth, most of the African-Americans worked as unskilled laborers but were not afraid to speak out. They were known to have participated more effectively in union organizations, strikes, and demonstrations than the white workers. Black women, who were overwhelmingly employed in household service, also struggled for workplace justice by contesting their white employer’s exploitative demands. Initially, the black population supported the Republican Party until they perceived that white Republicans resisted black demands for equal education, government jobs, and more black legislators. The white citizens retaliated by using the law, customs, and sometimes violence to reassert their white supremacy.

In 1890, Cairo’s population had reached some 6,300 people, and not only was it a famous river town, but it also boasted seven railroad lines branching through Cairo. Unfortunately, the city was also experiencing increased racial polarization, tension, and violence by this time, which inhibited black activism until the Great Depression.

In the meantime, Cairo was still growing. Though steamboat traffic was dropping, more efficient barges were utilized, and overall traffic dramatically increased on the Ohio River. In 1900 alone, the Ohio River transported more than 14 million tons of goods and people, a figure that would not be surpassed until 1925.

Though the vast majority of the cargo traveling along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers was not being delivered to Cairo, instead headed for other large cities, the town was thriving as it exported many products from its lumber mills, furniture factories, and other businesses.

Though Cairo wouldn’t reach its peak population until 1907, at over 15,000 residents, the turn of the century was forecasting signs of decline. One of its most prominent businesses in the city was the many ferries that crossed the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, transporting hundreds of thousands of railroad cars each year. Until 1889, no railroad bridge crossed either the Ohio or the Mississippi River at or near Cairo. That changed, however, in 1905, when a railroad bridge was completed across the Mississippi River at Thebes, a small town northwest of Cairo. This dealt a heavy blow to Cairo’s status as a railroad hub. Traffic soon shifted to the new bridge at Thebes, decreasing the traffic through Cairo and eliminating the ferry operations.

Before long, the railroads began to bypass the city, and water seepage on the low-lying land created severe problems. One of Cairo’s mayors claimed it was the most serious obstacle preventing prosperity for the town. Many citizens began to consider their community an economic failure, and even newspaper editorialists commented on how businessmen preferred to rent homes instead of buying them: “They preferred to rent because they regard their stay in Cairo as temporary.”

The first decade of Cairo’s 20th-century history was also marred by a highly violent episode on November 11, 1909. On that date, Cairo was the scene of one of the most gruesome lynchings in American history when a black man named Will James, who was accused of murdering a shop-girl, and a white man, who was charged with murdering his wife, were lynched by a mob, which numbered in the thousands.

Will “Froggy” James, an African-American man, was charged with the rape and murder of white 22-year-old Annie Pelley, a shop clerk in Cairo. A report soon circulated that James had confessed to the crime, also implicating an accomplice named Alexander. Though the people asked for an immediate trial, the court put off the case. Anticipating trouble, the local Sheriff kept James hidden in the woods for two days to save him from the townspeople’s vengeance. However, the angry citizens tracked James down in the woods near Belknap, Illinois, some 29 miles northeast of Cairo. The angry mob forcibly took James from the Sheriff’s custody and returned him to Cairo. He was then taken to the most prominent square at 8th and Commercial Street to be hanged before thousands of cheering spectators. Just before the rope was placed around James’ neck, he reportedly said, “I killed her, but Alexander took the lead.”

In response, the crowd jeered: “We don’t want to hear him; string him up; kill him; burn him.” James was hanged from an arch at 8:00 p.m. However, when the rope broke, James was riddled with bullets. The body was then dragged by a rope for a mile to the crime scene and burned in the presence of at least 10,000 people. Many women were in the crowd, some of whom helped to hang and drag the body. His remains were then cut up for souvenirs before burning the rest. His half-burned head was then attached atop a pole in Candee Park at the intersection of Washington Avenue and Elm Street. The following day, nothing was left of his body other than bones.

Will James Lynching 1909.

With their blood-thirst boiling, part of the mob searched for James’ named accomplice – Alexander. However, they didn’t find him if such a man ever existed. In the meantime, the other part of the mob fled to the county jail, where they hammered at Henry Salzner’s cell for more than an hour. Salzner, a local photographer, had been charged with murdering his wife with an ax in August. The prisoner pled for mercy while protesting his innocence, but it was useless. The bars finally gave way, and the prisoner was dragged to a telegraph pole at Washington Avenue and 21st Street. He was lynched at 11:15 p.m. and, once dead, filled with bullets. Salzner’s body was left in the street and claimed by his father the next day.

The mob remained in a frenzy, and order was restored only after Governor Charles Deneen ordered eleven companies of the National Guard to proceed to Cairo. By morning, all was quiet; the mob had dispersed, and only a few persons on the lookout for Alexander were lurking about the streets. However, hundreds of men continued to search the riverfront, breaking into freight cars, hoping to find Alexander.

During the mob chaos, the Mayor and the Chief of Police were being guarded in their homes as the angry mob threatened them.

The following year, in 1910, a sheriff’s deputy was killed by another mob attempting to lynch a black man accused of snatching a white woman’s purse. Again, the National Guard was called in, and martial law was implemented until order could be restored.

Though the racial tension continued, the town continued to thrive. In 1910, the historic Gem Theatre opened its doors to much acclaim. Seating 685 people, it was a cultural hot spot in the town. Unfortunately, a fire gutted the theatre in 1934, but it was rebuilt two years later, including a new, elegant marquee. The Gem continued to operate for nearly another half-century before it was closed in 1978. Unfortunately, though the vintage theatre still stands, it has been long-vacant and has fallen into severe disrepair.

In the meantime, Cairo’s reputation was developing a “mean, hard edge,” which was backed up in 1917 when the city had the highest arrest rate in the state, with 15% of its population incarcerated at one time or another. This reputation, which would get worse before it was over, still lasts to this day, even though Cairo’s “meanness” is long past, and its citizens work together to do what they can to save their dying town.

Shipping along the Ohio River in Cairo, Illinois, in 1917.

Like many other cities across the continent, Cairo was hard hit by the 1930s and the Great Depression. The town’s population and fortunes began to dwindle.

In 1937, the focus changed to another potential disaster when the Ohio River swelled to record heights in February. The flooding inundated the towns of Paducah and Louisville, Kentucky, Cincinnati, Ohio, and scores of other smaller communities as the huge crest moved downstream to the Mississippi River. Newsreel cameramen and newspaper correspondents rushed into Cairo to report the anticipated catastrophe. Women and children were evacuated from the city, and a three-foot bulwark of timbers and sandbags was hastily built atop the levees. But, lucky for Cairo, the water rose swiftly to within four inches of the bulwark, wavered several hours, and began to recede slowly. Of all the cities on the lower Ohio River, Cairo alone withstood the flood.

Though the citizens saved the town from flooding, its rough reputation continued, as the same year, it had the highest murder rate in the state. At the same time, its prostitute population was estimated to be over 1,000. And, for Cairo, conditions would get even worse.

The United States Courthouse and post office was built in Cairo, Illinois, in 1942. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

In the early 1940s, 12 severe fires destroyed businesses, most of which were never rebuilt. However, a Federal Courthouse, including a post office, opened in 1942. The building continues serving as a post office and the District Court for Southern Illinois.

Making matters more complex, after World War II was over in 1945, the town suffered from extremely high unemployment rates rather than flourishing like many communities across the Midwest. This further increased its crime rate, making the city a haven for organized crime. By the 1950s, the Illinois Senate began investigating a $20 million bootlegging operation sending large amounts of bootlegged liquor into nearby “dry” states.

Several mobster groups operated in Cairo, running bootlegged liquor and profitable slot machine rackets. The various groups brought more violence to the city as the gangsters tried to squeeze out their rivals, smashing slot machines, firebombing cars, and killing each other. On July 19, 1950, $20,000 worth of gambling equipment was confiscated from simultaneous raids on six nightclubs and taverns in or near Cairo. Just a month later, at the height of the gambling raids, five State Police were charged with theft of $150 from slot machines confiscated during a raid in Cairo.

Over the years, Cairo’s population began to decline due to the violence and the decrease in river trade. This decline, however, would not lead to Cairo’s ultimate demise – instead, it was racism.

The first major push for racial equality occurred in 1946 when black teachers filed a lawsuit in federal court to secure equal pay. When famed attorney Thurgood Marshall argued the case the same year, the judge and defense counsel continuously referred to Marshall as a “boy.” Defense counsel then explained to the court how a comparable case in Tennessee had been handled by a distinguished attorney who knew what he was doing, unlike the “boy” in this case. When the Defense counsel had completed his pontificating speech, Marshall quietly stood up and thanked counsel for the compliments, then informed the court that he was the brilliant attorney who had handled the case in Tennessee. Marshall became the first African American justice on the United States Supreme Court in 1967 and served until 1991.

Six years later, in 1952, efforts were begun to integrate Cairo’s schools, but separate black schools would not be abolished until years later, in 1967.

By 1960, the town supported only about 9,000 people. That number would, unfortunately, drop more drastically over the next few decades as racial tensions in the town escalated into a full-blown “war.”

By this time, the old scars of racism had hardened, and Cairo’s racial divide was starkly drawn. The city’s black citizens couldn’t get work in white-owned businesses, and when rural whites from Kentucky and Missouri were hired instead of local blacks, the African Americans rebelled. By 1962, local freedom movements were breaking out in communities nationwide, though the national media seldom reported them.

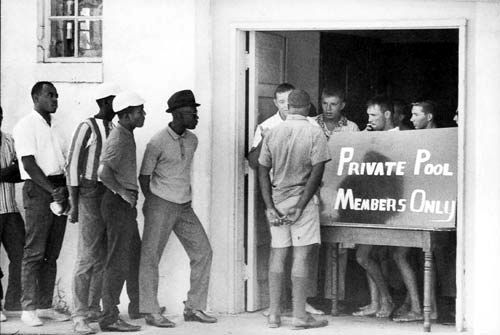

Demonstration of the segregated pool in Cairo, by Danny Lyon, 1962.

The city facilities were segregated entirely, including public housing, local parks, and seating in the courthouse. Almost all public and private offices employed only whites. During this time, the public swimming pool became a “private club” to keep out the black population. Requiring a “club” membership card to enjoy the calm waters of the pool, a large group of Civil Rights activists demonstrated at the pool in 1962, which spawned a white racist to deliberately drive his pickup truck into the demonstration, severely injuring a young African-American girl. The segregated swimming pool was finally closed in 1963 to avoid integration.

At about the same time, a demonstration to integrate the facility occurred at the local roller skating rink. When the group arrived, however, the skating rink owners had locked the doors, and the KKK was holding a meeting inside. Someone had stuck a note in the door with an ice pick that said, “No n____ here!”

Full-out “war” began in 1967 after the suspicious death of a 19-year-old black soldier on leave occurred while he was in police custody. Deemed to be suicide by the authorities, the black community disagreed and, led by Cairo native Reverend Charles Koen; they rose in protest against not only Hunt’s death but also a century of harsh segregation. Resulting in a riot, the whites quickly formed Vigilante groups, and the violence increased to such an extent that the Illinois National Guard was called in to quell racial hostilities.

That same year, Preston Ewing, Jr., Cairo’s NAACP president, wrote a letter to Adlai Stevenson, the state treasurer, reporting that Cairo banks would not hire blacks. The state responded by telling the banks they must hire blacks or it would remove its money from them.

Another black soldier, Wily Anderson, was on leave and killed by sniper bullets. A week later, a white deputy named Lloyd Bosecker was shot in retaliation. Cairo police charged four blacks in connection with the shooting and eleven others for violations of an anti-picketing law.

The Burkhart Factory, Cairo’s largest industry, allegedly practiced racial discrimination, refusing to hire African Americans. Factory management contended they were following population ratios. Ewing disregarded the argument and demanded that 50% of hires be black.

Little League baseball was canceled to keep black children from playing, and a private “all-white” school was established. By 1969, black citizens were not allowed to gather at sports activities, in local parks, or form marches without being threatened by local police or a Vigilante group called the White Hats.

A protest in Cairo, from the book Let My People Go: Cairo, Illinois 1967-73, by Jan Peterson Roddy, photo by Preston Ewing Jr. Most of these buildings are gone now, and in their place is a large empty lot.

The black community formed the United Front of Cairo in 1969 to counteract the White Hats. Fighting back, the coalition spawned an intense civil rights struggle to end segregation and create job opportunities. Residents were helped by what local whites called “outside agitators,” including the Reverend Jesse Jackson.

Though African Americans demanded jobs from white-owned businesses, owners refused to acknowledge their requests. As a result, the United Front then began to boycott white-owned businesses. Still, the establishments refused to hire them and chose instead to close up shop or go out of business rather than succumb to the demands of the black population.

In April 1969, Lieutenant Governor Paul Simon and a special committee appointed by the Illinois House of Representatives began investigating the events occurring in Cairo. The Illinois General Assembly soon ordered the White Hats to disband and called for the enforcement of civil rights laws and racial integration of city and county departments.

Even though the state government had become involved, white residents continued to hold mass meetings in public parks, while the African Americans held Civil Rights rallies in various churches.

In September 1969, Cairo’s mayor issued a statement prohibiting gathering two or more people, all marches, and picketing. However, the black protestors continued to protest. A federal court would later rule the mayor’s proclamation unconstitutional. Though the federal and state governments had gotten involved, they were ineffective in controlling the continued segregation and inequality in Cairo.

The demonstrations and violence continued into the 1970s, producing over 150 nights of gunfire, multiple marches, protests, and arrests; numerous businesses were bombed, and more declared bankruptcy.

By 1971, there was minimal left to picket as most downtown businesses had closed in Cairo. Photo from the book Let My People Go: Cairo, Illinois 1967-73, by Jan Peterson Roddy, photo by Preston Ewing Jr.

By 1970, the population had dropped to a little over 6,000 people, and by the following year, there was very little left to picket as most of the downtown businesses had closed. The boycott continued for the remaining establishments for the rest of the decade.

Once, Commercial Street was lined with businesses—a Hallmark store, the Mode-O-Day, the Khourie Brothers Department Store—in front of which stood the Hamburger Wagon, serving popcorn, greasy burgers, and flavored sodas. Other retail stores flourished, such as Florsheim Shoes, a music store, a photography studio, banks, auto dealerships, gas stations, and restaurants. Elegant old street lamps lined the street. They are all closed now, and most of the buildings are gone.

Elsewhere in the city, some 40 small neighborhood grocery stores once thrived. During our visit in 2010, we did not find a single open grocery store. As half the town sat on the concrete levee wall watching, Cairo’s residents were once entertained by numerous speedboat races on the Ohio River. Not anymore. Another entertainment venue — the Gem Theatre — closed its doors forever in 1978 after operating for nearly 70 years.

Cairo’s 44-bed hospital closed in 1986, the town soon lost its bus service, and in 1988, the City of New Orleans, operating on the rail line, made its last stop. Though the passenger depot initially built by the Illinois Central Railroad still stands, the trains no longer stop for passengers.

In the end, Cairo would become the city that died from racism. By 1990, the town sported a population of little less than 5,000. Its citizens tried valiantly to save the town when Riverboat Gambling was legalized the same year. Enacted partially to revitalize dying towns, it was the perfect opportunity for little Cairo to have a second chance. However, the State of Illinois awarded the license to nearby Metropolis, some 40 miles northwest on the Ohio River, dashing all hopes of the town’s opportunity to revitalize its economy and population. By the year 2,000, Cario’s population had dropped to only about 3,600 residents. Today, it is called home to about 2,200 people.

Commercial Avenue in Cairo is all but empty today. On the right side of the street, these buildings once held the W.T. Wall & Co. Department Store, the Cairo Public Utility Commission, M. Snower & Co., a garment manufacturer, and more. On the left side, where the empty lots are today, once held a Hallmark Store, the S.H. Kress & Co. Variety Store, a music store, and more. The Rhodes-Burford Furniture Store sign was still in place at the far end of the left side of the street. It was one of the last large businesses to close. By Photo by Kathy Alexander.

Preston Ewing Jr., Cairo’s unofficial historian, former president of the local NAACP chapter, city treasurer, and participant in the Civil Rights Movement in Cairo, described the town as “poor, black, and ugly.” Further, not having unrealistic expectations, he said, “Our goal should be to stabilize Cairo, not talk about growth. Potential employers will go where there is greater viability and infrastructure to support businesses.” Things were so bad in 1990 that its principal advised the Cairo High School graduating class to leave the town.

Built to support over 15,000 people, Cairo is a semi “ghost town” today, by definition — any historical town or site that leaves evidence of its previous glory. A third of its population is below the poverty line. The city is predominately African-American at almost 72%, compared to Caucasian at about 28%. The median income for a household in the city was just $21,607 in the 2000 census. The town continued to face significant socio-economic challenges, including education issues, high unemployment rates, and lack of a commercial tax base, which contributed to the sadness of Cairo. In the 2010 census, the median income for a household in the city dropped to $16,682.

The Famous Building at 702-704 Commercial Avenue was a general-purpose commercial building housing a mercantile establishment on the ground floor and offices above. The building still stands today. By Kathy Alexander.

The city and its residents have worked hard over the recent years to stabilize the small town; however, these attempts are often short-lived, as there is simply no money. The real estate in Cairo is cheap, and many, intrigued by the prospect of building a business, have taken the opportunity to start in Cairo. However, business is slow, and residents wonder why these businesses started in their small towns. Additionally, many residents see these newcomers as temporary – being too used to people coming to help and then leaving. After years of turmoil, Cairo’s residents are often untrusting.

For many years, there were efforts to promote the area for tourism — focusing on its rich history, magnificent river views, and historic buildings. However, the lack of money has continued to hurt the town. South of Cairo, the historic site of Fort Defiance, once an Illinois State Park that was given over to the City of Cairo, is now abandoned. Everywhere, there are sad reminders that less than 2,500 people now live in a city designed for many more. Alexander County is one of the poorest in Illinois. Without businesses that pay taxes, the town and county cannot afford to provide basic services, much less promote itself. Many of its residents are tired of telling the story of their blighted town and want to be left alone.

In the last decade, numerous buildings have been torn down in Cairo for safety and “cleaning up” the city. The most recent demolishment includes the Elmwood and McBride housing projects, which were in poor condition and razed in 2019. This demolition created a housing crisis for numerous residents, which was yet another blow to this isolated rural town. Unfortunately, after decades of white flight and economic stagnation, what’s left is an expanse of abandoned buildings, bulldozed lots, and forgotten history.

Still, this historic city provides history buffs and photographers with opportunities to explore Cairo’s historic downtown, beautiful churches, and government structures that continue to stand. The community continues to fight for its existence. Hopefully, these efforts will work as the clock continues to tick on Cairo, which, without revitalization, is destined to become a true “ghost town.”

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

See our Cairo Photo Gallery HERE

Also See:

African Americans – From Slavery to Equality

Lost Landmarks & Vanished Sites

Lynchings & Hangings in American History

Sources:

Federal Writers’ Project; Illinois: A Descriptive and Historical Guide; A.C. McClurg & Co, Chicago, IL; 1939.

Hays, Christopher K.; The African American Struggle For Equality And Justice In Cairo, Illinois, 1865-1900; Illinois Historical Journal, 1997

Roddy, Jan Peterson, and Ewing, Preston, Jr.; Let My People Go: Cairo, Illinois, 1967-1973, Southern University Press, Carbondale, Illinois, 1996

Smith, Aaron Lake; Trying to Revitalize a Dying Small Town, 2010, Time

Turner, Paul; Cairo Seemed Destined For Greatness; Chicago Reader

Jones, Rachel; Singer Evokes Turbulent History of Cairo, Illinois, 2006, NPR