By James B. Gillett in 1921

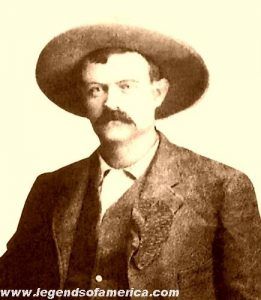

Sam Bass

Sam Bass was a noted outlaw and train robber who led two gangs during the days of the Wild West – the Black Hills Bandits between 1876-1877 and the Bass Gang of Texas that operated in 1877-1878

The noted train robber was born in Mitchell, Indiana, on July 21, 1851, to Daniel and Elizabeth Jane Bass. He came to Texas while still little more than a boy and worked for Sheriff Everhart of Denton County until he reached manhood. While still an exemplary and honest young man, Bass came into possession of a small race pony, a little sorrel mare. When most of the neighborhood boys met in Denton on Saturday evenings, Bass raced his pony with much success. Everhart soon noticed that Sam was beginning to neglect his work because of his pony, and knowing only too well what this would lead to, he advised Sam to sell his mare. Bass hesitated, for he loved the animal. Finally, matters came to such a point that Mr. Everhart told Sam he would have to get rid of the horse or give up his job. Bass promptly quit, which was probably the turning point in his life.

Bass left Denton County in the spring of 1877 and traveled to San Antonio. Many cattlemen were gathered to arrange the spring cattle drive to the north. Joel Collins, who was planning to drive a herd from Uvalde County to Deadwood, South Dakota, hired Bass as a cowboy. After six months on the trail, the herd reached Deadwood and was sold, and Collins paid off all the cowboys.

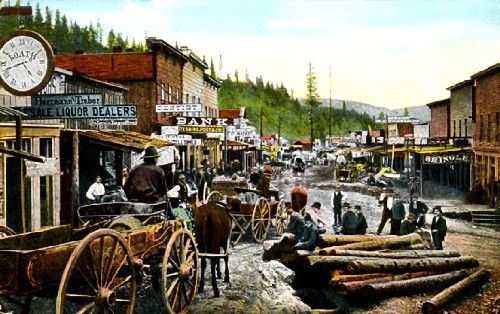

At that period, Deadwood as a great, wide-open mining town. Adventurers, gamblers, mining, and cattlemen all mingled together. Though Joel Collins had bought his cattle on credit and owed the greater part of the money he had received for them to his friends in Texas, he gambled away all the money he had received for the herd. When he sobered up and realized all his money was gone, he did not have the moral courage to face his friends and creditors at home. He became desperate and with a band of his cowboys, known as the Black Hills Bandits, held up and robbed several stagecoaches. These robberies brought Collins very little booty, but they started Sam Bass on his criminal career.

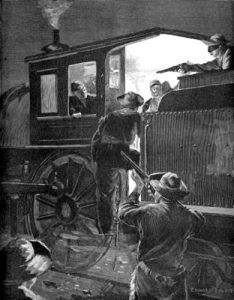

In the fall of 1877, Collins, accompanied by Bass, Jack Davis, Jim Berry, Bill Heffridge, and Tom Nixon, left Deadwood and drifted down to Ogallala, Nebraska. Here, he conceived, planned, and carried into execution one of the boldest train robberies that ever occurred in the United States up to that time. When all was ready, these six armed and masked men held up the Union Pacific train at Big Springs, a small station a few miles beyond Ogallala. The bandits entered the express car and ordered the messenger to open the safe. The latter explained that the safe had a time lock and could only be opened at the end of the route. One of the robbers then began to beat the messenger over the head with a six-shooter, declaring he would kill him if the safe were not opened. Bass, always of a kindly nature, pleaded with the man to desist, declaring he believed the messenger was telling the truth. Just as the robbers were preparing to leave the car without a dime, one of them noticed three stout little boxes piled near the big safe. The curious bandit seized a coal pick and knocked off the lid of the top box. He exposed $20,000 in shining gold coin to his great joy and delight! The three boxes each held a similar amount, all in $20 gold pieces.

After looting the boxes, the robbers went through the train and systematically robbed the passengers of about $1,300. By daylight, the bandits had hidden their booty and returned to Ogallala. They hung around town for several days while railroad officials, U.S. Deputy Marshals, and sheriff’s parties were scouring the country for the train robbers.

Collins and his men frequented a large general merchandise store. In this store was a clerk who had once been an express messenger on the Union Pacific and was well acquainted with the officials of that company. I have forgotten his name, but I will call him Moore for the sake of clarity in my narrative. Of course, the great train robbery was the talk of the town. Moore conversed with Collins and his gang about the hold-up, and the bandits declared they would help hunt the robbers if there was enough money in it.

Moore’s suspicions were aroused, and he became convinced that Collins and his band were the real hold-up men. However, he said nothing to anyone about this belief but carefully watched the men. Finally, Collins came to the store and, after buying clothing and provisions, told Mr. Moore that he and his companions would return to Texas and be up the trail the following spring with another herd of cattle. When Collins had been gone a day’s travel, Mr. Moore hired a horse and followed him. He soon found the route the suspects were traveling, and on the second day, Moore came upon them suddenly while they were stopping at a roadside farmhouse for something to eat. Moore passed by without being noticed and secreted himself near the trail. In a short time, Collins and his men passed on, and Moore followed them until they went into camp. When it was dark, the amateur detective crept up to the bandits, but they had gone to sleep, and he learned nothing.

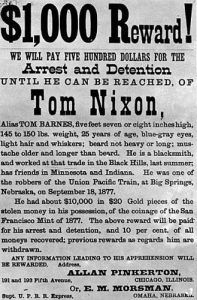

The next day Moore resumed the trail. He watched the gang make their camp for the night and again crept up to within a few yards of his suspects. The bandits had built a big fire and were laughing and talking. Soon they spread out a blanket and, to Moore’s great astonishment, brought out some money bags and emptied upon the blanket sixty thousand dollars in gold. From his concealed position, he heard the robbers discuss the hold-up. They declared they did not believe anyone had recognized or suspected them and decided it was now best for them to divide the money, separate in pairs, and go their way. The coin was stacked in six piles, and each man received $10,000 in $20 gold pieces. It was further decided that Collins and Bill Heffridge would travel back to San Antonio, Texas; Sam Bass and Jack Davis were to go to Denton County, Texas, while Jim Berry and Tom Nixon were to return to the Berry home in Mexico, Missouri.

As soon as Moore had seen the money and heard the robbers’ plans, he slipped back to his horse, mounted, and rode day and night to reach Ogallala.

He notified the railroad officials of what he had seen and gave the names and descriptions of the bandits and their destinations. This information was broadcast over southern Nebraska, Kansas, Indian Territory, and Texas. In the fugitive list sent to each of the companies of the Frontier Battalion of Texas Rangers, Sam Bass was thus described: “Twenty-five to twenty-six years old, 5 feet 7 inches high, black hair, dark brown eyes, brown mustache, large white teeth, shows them when talking; has very little to say.”

A few days after the separation of the robbers, Joel Collins and Bill Heffridge rode into a small place in Kansas called Buffalo Station. They led a pack pony. Dismounting from their tired horses and leaving them standing in the shade of the store building, the two men entered the store and made several purchases. The railroad agent at the place noticed the strangers ride up. He had, of course, been advised to be on the lookout for the train robbers. He entered the store and, in a little while, engaged Collins in conversation. While talking to the robber, he pulled his handkerchief out of his coat pocket and exposed a letter with his name thereon. The agent was a shrewd man. He asked Collins if he had not driven a herd of cattle up the trail in the spring. Collins declared he had and finally admitted that his name was Collins in answer to a direct question.

Five or six hundred yards from Buffalo Station, a lieutenant of the United States Army had camped a troop of ten men scouting for the train robbers. As soon as Collins and Heffridge remounted and resumed their way, the agent ran quickly to the soldiers’ camp, pointed out the bandits to the lieutenant, and declared, “There go two of the Union Pacific train robbers!”

Posse

The army officer mounted his men and pursued Collins and Heffridge. When he overtook the two men he told them their descriptions tallied with those of some train robbers he was scouting for and declared they would have to go back to the station and be identified. Collins laughed at the idea and declared that he and his companion were cattlemen returning to their homes in Texas. They reluctantly turned and started back with the soldiers. After riding a few hundred yards, the two robbers held a whispered conversation. Suddenly the two pulled their pistols and attempted to stand off the lieutenant and his troop. The outlaws were promptly shot and killed. On examining their packs, the soldiers found tied up in the legs of a pair of overalls $20,000 in gold. Not a dollar of the stolen money had been used, and there was no doubt about the man’s identity.

Not long after they had divided up in Nebraska, Jim Berry appeared at his home in Mexico, Missouri. At once, he deposited quite a lot of money in the local bank and exchanged $3,000 in gold for currency, explaining his possession of the gold by saying he had sold a mine in the Black Hills. In three or four days, the county sheriff learned of Berry’s deposits and called the bank to see the new depositor’s gold. His suspicion became certain when he found that he had deposited $20 gold pieces.

That night the sheriff with a posse rounded up at Berry’s house, but the suspect was not there. The home was well provisioned, and the posse found many articles of newly purchased clothing. Just after daylight, while searching the place, the sheriff heard a horse whinny in some timber nearby. Upon investigating, he suddenly came upon Jim Berry sitting on a pallet. Berry discovered the officer at about the same time and attempted to escape by running. He was fired upon, one bullet striking him in the knee and badly shattering it. He was taken to his home and given the best medical attention, but gangrene set in, and he died in a few days. Most of his $10,000 was recovered. Tom Nixon evidently quit Berry somewhere en route, for he made good his escape with his ill-gotten gain and was never apprehended.

After the separation in Nebraska, Sam Bass and Jack Davis sold their ponies and bought a light spring wagon and a pair of workhorses. They placed their gold pieces in the bottom of the wagon, threw their bedding and clothes over it, and in this disguise, traveled through Kansas and Indian Territory to Denton County, Texas. During their trip through the territory, Bass afterward said he camped within 100 yards of a detachment of cavalry. After supper, he and Davis visited the soldiers’ camp and chatted with them until bedtime. The soldiers said they were on the lookout for some train robbers that had held up the Union Pacific in Nebraska, never dreaming for a moment that they were conversing with two of them. The men also mentioned that two robbers had been reported killed in Kansas.

This rumor put Bass and Davis on their guard, and on reaching Denton County, Texas, they hid in the Elm Bottoms until Bass could interview some of his friends. Upon meeting them, he learned that the names and descriptions of every one of the Union Pacific train robbers were in possession of the law officers; that Collins, Heffridge, and Berry had been killed; and that every sheriff in North Texas was on the watch for Davis and himself. Davis at once begged Bass to go with him to South America, but Bass refused, so Davis bade Sam goodbye and set out alone. He was never captured. On his deathbed, Bass declared he had once received a letter from Jack Davis written from New Orleans, Louisiana, asking Bass to come there and go into the business of buying hides.

Bass had left Denton County early in the spring an honest, sincere, and clean young man. By falling with evil associates, he had become, within a few months, one of the most daring outlaws and train robbers of his time. Before he had committed any crime in the state, the officers of North Texas made repeated efforts to capture him for the big reward offered by the Union Pacific and the express company but, owing to the nature of the country around Denton and the friends Bass had as long as his gold lasted, met with no success.

Bass’ money soon attracted several desperate and daring men to him. Henry Underwood, Arkansas Johnson, Jim Murphy, Frank Jackson, Pipes Herndon, and William Collins, — the last one, a cousin of Joel Collins — and two or three others joined him in the Elm Bottoms. Naturally, Bass was selected as the leader of the gang. It was not long before the outlaw chief planned and executed his first train robbery in Texas: that at Eagle Ford, a small station on the Texas Pacific Railroad a few miles out of Dallas. In quick succession, the bandits held up two or three other trains, the last at Mesquite Station, ten or twelve miles east of Dallas. From this robbery, they secured about $3,000. They met with opposition here, for the conductor, though armed with only a small pistol, fought the robbers and slightly wounded one of them.

The whole state was now aroused by the repeated train hold-ups. General John B. Jones hurried to Dallas and Denton to look over the situation and arranged to organize a company of Texas Rangers at Dallas. Captain June Peak, a very able officer, was given the command. No matter how brave a company of recruits, it takes time and training to get results from them, and when this raw company was thrown into the field against Bass and his gang, the bandit leader played with it as a child plays with toys. Counting the thirty Rangers and the different sheriffs’ parties, there were probably 100 men pursuing the Bass Gang. Sam played hide-and-seek with them all and, it is said, never ranged any farther west than Stephens County or farther north than Wise County. He was generally in Dallas, Denton or Tarrant Counties. He would frequently visit Fort Worth or Dallas at night, ride up with his men to some outside saloon, get drinks all around and then vamoose.

Finally, in a fight at Salt Creek in Wise County, Captain June Peak, and his Texas Rangers killed Arkansas Johnson, Bass’ most trusted lieutenant. Either just before or soon after this battle, the Rangers captured Pipes Herndon and Jim Murphy and drove Bass and his two remaining companions out of North Texas. At that time, the state had, on the frontier of Texas, six companies of veteran Rangers. They were finely mounted, highly equipped, and were the best-mounted police in the world. Anyone of those highly trained commands could have broken up the Sam Bass Gang in half the time it took command of new men.

After the fight on Salt Creek, only Sam Bass, Seaborn Barnes, and Frank Jackson were left of the once formidable gang. These men had gained nothing from their four train robberies in North Texas and were so hard-pressed by the law officers on all sides that Bass reluctantly decided to leave the country and try to make his way to Mexico. General Jones learned of the contemplated move through some pretended friends of Bass. He, with Captain Peak and other officers, approached Jim Murphy, one of Bass’ gang captured about the time of the Salt Creek fight, who was awaiting trial by the Federal authorities for train robbery, and promised they would secure his release if he would betray his friend.

Murphy hesitated and said his former chief had been kind to his family, had given them money and provisions, and that it would be ungrateful to betray his friend. The general declared he understood Murphy’s position fully, but Bass was an outlaw, a pest to the country, who was preparing to leave the state and so could no longer help him. General Jones warned Murphy that the evidence against him was overwhelming and was certain to send him to the Federal prison — probably for life — and exhorted him to remember his wife and his children. Murphy finally yielded and agreed to betray Bass and his gang at the first opportunity.

According to the plan agreed upon, Murphy was to give bond, and when the Federal court convened at Tyler, Texas, a few weeks later, he was not to show up. It would then be published all over the country that Murphy had skipped bond and rejoined Bass. This was carried out to the letter. Murphy joined Bass in the Elm Bottoms of Denton County and agreed to rob a train or bank and get out of the country. Some of Bass’ friends, suspicious of Murphy’s bondsmen, wrote Sam that Murphy was playing a double game and advised him to kill the traitor at once. Bass immediately confronted Murphy with these reports and reminded him how freely he had handed out his gold to Murphy’s family. Bass declared he had never advised or solicited Jim to join him, and said it was a low-down, mean and ungrateful trick to betray him. He told Murphy plainly if he had anything to say to say it quickly. Barnes agreed with his chief and urged Murphy’s death.

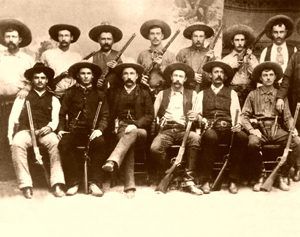

Sam Bass Gang, photo courtesy City of Roundrock, Tx and Robert G. McCubbin, Jr.

The plotter denied any intention of betraying Bass and offered to take the lead in any robbery. Bass should plan and be the first to enter the express car or climb over the bank railing. Bass and Barnes were angry and decided to kill the liar at once. Frank Jackson had taken no part in the conversation, but, he now declared he had known Murphy since he was a little boy, and he was sure Murphy was sincere and meant to stand by them through thick and thin. Bass was not satisfied and insisted that Murphy be murdered then and there.

Jackson finally told Bass and Barnes that they could not kill Murphy without first killing him. Although the youngest of the party at just 22 years old, Jackson had great influence over his chief. He was brave and daring, and Bass could not get along without him at that time, so his counsel prevailed, and Murphy was spared. The bandits then determined to quit the country. They planned to rob a small bank somewhere en route to Mexico and thus secure the funds needed to facilitate their escape, for they were all broke.

Bass, Seaborn Barnes, Frank Jackson, and Jim Murphy left Denton County early in July 1878. With his usual boldness, Bass, after he had passed Dallas County, made no attempt at concealment but traveled the public highway in broad daylight. Bass and Barnes were still suspicious of Murphy and never let him out of their sight, though they refused to talk to or associate with him in any way. When Bass reached Waco, the party camped on the outskirts of the town and remained there for two or three days. They visited the town each day, looked over the situation, and saw much gold and currency in one bank. Jackson was enthusiastic and wanted to rob it at once. Being more careful and experienced, Bass thought it too hazardous an undertaking, for the run through crowded streets to the outskirts of the city was too far; and so vetoed the attempt.

While in Waco, the gang stepped into a saloon to get a drink. Bass laid a $20 gold piece on the bar and remarked, “There goes the last twenty of the Union Pacific money and d–n little good it has done me.” On leaving Waco, the robbers stole a fine mare from a farmer named Billy Mounds and traveled the main road to Belton. They were now out of money and planned to rob the bank in Round Rock, Texas.

General Jones was, by then, getting anxious over the gang. Not a word had been heard from Jim Murphy since he had rejoined the band, for he had been so closely watched that he had had no opportunity to communicate with the authorities. It seemed as if he would be forced to participate in the next robbery, despite himself.

At Belton, Sam sold an extra pony his party had after stealing the mare at Waco. The purchaser demanded a bill of sale as the vendors were strangers in the country. While Bass and Barnes were in a store writing out the required document, Murphy seized the opportunity to dash off a short note to General Jones, saying, “We are on our way to Round Rock to rob the bank. For God’s sake, be there to prevent it.” As the post office adjoined the store, the traitor succeeded in mailing his letter of betrayal just one minute before Bass came out on the street again. The gang continued to Round Rock and camped near the old town, which is situated about one mile north of New Round Rock. The bandits concluded to rest and feed their horses for three or four days before attempting their robbery. This delay was providential, giving General Jones time to assemble his Rangers to repel the attack.

After Major Jones was made Adjutant-General of Texas, he sent a small detachment of four or five Rangers to camp on the Capitol grounds at Austin. He drew his units from different companies along the line. Each unit would be detailed to camp in Austin, and about every six weeks or two months, the detail would be relieved by a squad from another company. It will readily be seen that this was a wise policy, as the detail was always on hand and could be sent in any direction by rail or on horseback at short notice. Besides, General Jones was devoted to his Texas Rangers and liked to have them around where he could see them daily. At that time, four men from Company “E” — Corporal Vernon Wilson and Privates Dick Ware, Chris Connor, and George Harold — were camped at Austin. The corporal helped General Jones as a clerk in his office but was in charge of the squad on the Capitol grounds, slept in camp, and had his meals with them.

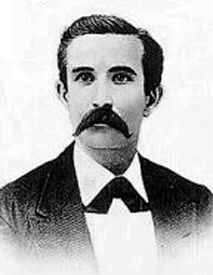

John B. Jones

When General Jones received Murphy’s letter, he was astonished at Bass’ audacity in approaching within fifteen or twenty miles of the state capital, the very headquarters of the Frontier Battalion, to rob a bank. The letter was written at Belton, Texas, and received at the Adjutant-General’s office on the last mail in the afternoon. The company of Rangers nearest Round Rock was Lieutenant Reynolds’ Company “E,” stationed at San Saba, 115 miles distant. There was no telegraph to San Saba at that time. General Jones reflected a few moments after receipt of the letter and then arranged his plan rapidly.

He turned to Corporal Wilson and told him that Sam Bass and his gang were, or soon would be, at Round Rock, Texas, to rob the bank there.

“I want you to leave at once to carry an order to Lieutenant Reynolds. It is 65 miles to Lampasas, and you can make that place early enough in the morning to catch the Lampasas and San Saba stage. You must make that stage at all hazards, save neither yourself nor your horse, but get these orders to Lieutenant Reynolds as quickly as possible,” he ordered.

Corporal Wilson hurried to the livery stable, saddled his horse, and got away from Austin on his wild ride just at nightfall. Wilson reached Lampasas at daylight the next morning and made the outgoing stage to San Saba. From Lampasas to San Saba was 50 miles, and it took the stage all day to make the trip. As soon as he landed in town, Corporal Wilson hired a horse and galloped three miles down to Lieutenant Reynolds’ camp and delivered his orders.

After dispatching Corporal Wilson to Lieutenant Reynolds, General Jones hurried over to the Ranger camp on the Capitol grounds and ordered the three Rangers, Ware, Connor, and Harold, to proceed to Round Rock, put their horses in Highsmith’s livery stable, and keep themselves concealed until he could reach them himself by train next morning. The following morning General Jones went to Round Rock. He carried with him from Austin Morris Moore, an ex-Ranger but then deputy sheriff of Travis County. On reaching his destination, the general called on Deputy Sheriff Grimes of Williamson County, who was stationed at Round Rock, and told him Bass was expected to rob the bank and that a scout of Rangers would be in town as soon as possible. Jones advised Deputy Grimes to keep a sharp lookout for strangers but on no account to attempt an arrest until the Rangers could arrive.

In the meantime, Sergeant Nevill delivered Reynolds’ orders to the Ranger camp at San Saba, which were brief and to the point: “Bass is at Round Rock. We must be there as early as possible tomorrow. Make a detail of eight men and select those that have the horses best able to make a fast run. And you, with them, report to me here at my tent, ready to ride in thirty minutes.”

First Sergeant C. L. Nevill, Second Sergeant Henry McGee, Second Corporal J. B. Gillett, Privates Abe Anglin, Dave Ligon, Bill Derrick, and John R. and W. L. Banister were selected for the detail. Lieutenant Reynolds ordered two of our best little pack mules hitched to a light spring hack, for he had been sick and was not in any condition to make the journey horseback.

In 30 minutes from the time Corporal Wilson reached camp, the Rangers were mounted, armed, and ready to go. Lieutenant Reynolds took his seat in the hack, threw some blankets in, and Corporal Wilson, who had not had a minute’s sleep for over 36 hours, lay down to get a little rest as we moved along. The Rangers left their camp on the San Saba River just at sunset and traveled in a fast trot the entire night.

The sun was coming up when the Rangers as they crossed the North Gabriel River, 15 miles south of Lampasas. They had ridden 65 miles and had 45 miles yet to go before reaching Round Rock. They halted on the Gabriel River for a breakfast of bread, broiled bacon, and black coffee, and the horses were fed. After just 30 minutes, they were off again, reaching the vicinity of old Round Rock between 1 and 2 o’clock in the afternoon of Friday, July 19, 1878. The Rangers camped on the banks of Brushy Creek while the lieutenant drove into New Round Rock to report his arrival to General Jones.

Bass had decided to rob the bank at Round Rock on Saturday, the 20th. After his gang had eaten dinner in camp Friday evening, they saddled their ponies and started to town to take a last look at the bank and select a route to follow in leaving the place after the robbery. As they left camp, Jim Murphy, knowing that the bandits might be set upon at any time, suggested that he stop at May’s store in Old Round Rock and get a bushel of corn, as they were out of feed for their horses. Bass, Barnes, and Jackson rode on into town, hitched their horses in an alley just back of the bank, passed that building, and made a mental note of its situation. They then went up the town’s main street and entered Copprel’s store to buy some tobacco. As the three bandits passed into the store, Deputy Sheriff Moore, who was standing on the sidewalk with Deputy Sheriff Grimes, said he thought one of the newcomers had a pistol.

“I will go in and see,” replied Grimes.

“I believe you have a pistol,” remarked Grimes, approaching Bass and trying to search him.

“Yes, of course, I have a pistol,” said Bass. At the words, the robbers pulled their guns and killed Grimes as he backed away to the door. He fell dead on the sidewalk. They then turned on Moore and shot him through the lungs as he attempted to draw his weapon.

At the crack of the first pistol shot, Dick Ware, who was seated in a barbershop only a few steps away waiting his turn for a shave, rushed into the street and encountered the three bandits just as they were leaving the store. Seeing Ware rapidly advancing on them, Bass and his men fired on the Ranger at close range, one of their bullets striking a hitching post within six inches of Ware’s head and knocking splinters into his face. This assault never halted Ware for an instant. He was as brave as courage itself and never hesitated to take the most desperate chances when the occasion demanded it. For a few minutes, Dick fought the robbers single-handedly. Coming uptown from the telegraph office, General Jones ran into the fight. He was armed with only a small Colt’s double action pistol but threw himself into the fray. Connor and Harold had now come up and joined in the fusillade. Seeing the robbers on foot and almost within his grasp, the general drew in close and urged his men to strain every nerve to capture or exterminate the desperadoes. By this time, every man in the town that could secure a gun joined in the fight.

The bandits had now reached their horses, and realizing their situation was critical, they fought with the energy of despair. If ever a train robber could be called a hero this boy, Frank Jackson, proved himself one. Barnes was shot down and killed at his feet, Bass was mortally wounded and unable to defend himself or even mount his horse while the bullets continued to pour in from every quarter. With heroic courage, Jackson held the Rangers back with his pistol in his right hand while he unhitched Bass’ horse with his left and assisted him into the saddle. Then, mounting his own horse, Jackson and his chief galloped out of the jaws of hell itself. In their flight, they passed through Old Round Rock, and Jim Murphy, standing in the door of May’s store, saw Jackson and Bass go by on the dead run. The betrayer noticed that Jackson was holding Bass, pale and bleeding, in the saddle.

Lieutenant Reynolds, entering Round Rock, came within five minutes of meeting Bass and Jackson in the road. Before he reached town, he met posses of citizens and Rangers in pursuit of the robbers.

When the fugitives reached the cemetery, Jackson halted long enough to secure a Winchester they had hidden in the grass there, then left the road and were lost for a time. The fight was now over and the play spoiled by two over-zealous deputies in bringing on an immature fight after they had been warned to be careful. Naturally, Moore and Grimes should have known that the three strangers were the Sam Bass Gang.

Lieutenant Reynolds started Sergeant Nevill and his Rangers early the next morning in search of the flying bandits. After traveling in the direction, the robbers were last seen, they came upon a man lying under a large oak tree. Seeing the armed Rangers, the man called out to not to shoot, saying he was Sam Bass, the man we were hunting.

After entering the woods the evening before, Bass became so sick and faint from loss of blood that he could go no farther. Jackson dismounted and wanted to stay with his chief, declaring he was a match for all their pursuers.

“No, Frank,” replied Bass. “I am done for.”

The wounded leader told his companion to tie his horse near at hand so he could get away if he felt better during the night. Jackson was finally prevailed upon to leave Bass and make his own escape.

When daylight came, Saturday morning, Bass got up and walked to a nearby house. As he approached the place, a lady, seeing him coming holding his pants up and all covered with blood, left her house and started to run off, as she was alone with a small servant girl. Bass saw she was frightened and called to her to stop, saying he was perishing for a drink of water and would return to a tree not far away and lie down if she would only send him a drink. The lady sent him a quart cup of water, but the poor fellow was too far gone to drink it. He was found under this tree one hour later. He had a wound through the center of his left hand, the bullet having pierced the middle finger.

Bass’ death wound was given him by Dick Ware, who used a .45 caliber Colt’s long-barreled six-shooter. The ball from Ware’s pistol struck Bass’ belt and cut two cartridges in pieces, and entered his back just above the right hip bone. The bullet badly mushroomed and made a fearful wound that tore the victim’s right kidney all to pieces. From the moment he was shot until his death three days later, Bass suffered untold agonies. As he lay on the ground Friday night where Jackson had left him the wounded man tore his undershirt into more than one hundred pieces and wiped the blood from his body.

Bass was taken to Round Rock and given the best of medical attention but died the following day, Sunday, July 21, 1878. While he was yet able to talk, General Jones appealed to Bass to reveal to the state authorities the names of the confederates he had had that they might be apprehended.

“Sam, you have done much evil in this world and have only a few hours to live. Now, while you have a chance to do the state some good, please tell me who your associates were in those violations of the laws of your country.”

Sam replied that he could not betray his friends and that he might as well die with what he knew in him.

Sam Bass was buried in the cemetery at Old Round Rock. A small monument was erected over his grave by a sister. Its simple inscription reads:

Samuel Bass

Born July 21st, 1851

Died July 21st, 1878

A brave man reposes in death here. Why was he not true?

Frank Jackson made his way back into Denton County and hung around for some time, hoping to get an opportunity to murder the betrayer of his chief. Jackson declared if he could meet Jim Murphy, he would kill him, cut off his head, and carry it away in a gunny sack.

Murphy returned to Denton but learned that Jackson was hiding in the Elm Bottoms, awaiting a chance to slay him. He thereupon asked permission of the sheriff to remain about the jail for protection. While skulking about the prison, one of his eyes became infected. A physician gave him some medicine to drop into the diseased eye, at the same time cautioning him to be careful as the fluid was a deadly poison. Murphy drank the entire contents of the bottle and was dead in a few hours. Remorse, no doubt, caused him to end his life.

By James Buchanan Gillett, 1921. Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated December 2018.

Also See:

Texas Rangers – Order Out of Chaos

About the Article and Author: This article was written by James Buchanan Gillett, a Texas Ranger, author, and rancher. It was included in a book he wrote in 1921 entitled Six Years with The Texas Rangers. The text as it appears here is not verbatim, as it has been added to and heavily edited for corrections and clarifications.