Cheyenne Dog Soldier

By W.S. Campbell in 1921

The awesome warriors were “armed to the teeth with revolvers and bows… proud, haughty, defiant as should become those who are to grant favors, not beg them.”

— An Ohio reporter covering the negotiations at Medicine Lodge, Kansas on October 27, 1867.

Of all the typical Plains tribes, the Cheyenne were most distinguished for warlike qualities. Few in number, they overcame or held in check most of the peoples who opposed them, and when the westward movement of European civilization began, they made more trouble than all the rest combined. In short, they were preeminently warriors among peoples whose trade was war.

As in other Plains tribes, the warriors of the Cheyenne were organized into societies or orders. These societies were fraternal, military, and semi-religious organizations with special privileges, duties, and dress, usually tracing their origin to some mythical culture hero or medicine man. Each society had its own songs and secret ritual and exacted certain observances and standards of its members.

Of these organizations, none played such a part in the history of the Plains as the “Dog Soldiers” of the Cheyenne.

The best version of the story of its origin is that recorded by George A. Dorsey in The Cheyenne Ceremonial Organization, 1905:

“The Dog-Man (Dog Soldier) Society was organized after the organization of the other societies, by a young man without influence, but who was chosen by the great Prophet. One morning the young man went through the entire camp and to the center of the camp circle, announcing that he was about to form a society. No one was anxious to join him, so he was alone all that day. The other medicine men had had no difficulty in establishing their societies, but this young man, when his turn came to organize, was ridiculed, for he was not a medicine-man, and had no influence to induce others to follow his leadership.

That evening he was sad, and he sat in the midst of the whole camp. He prayed to the Great Prophet and the Great Medicine Man to assist him. At sunset, he began to sing a sacred song. While he sang the people noticed that now and then the large and small dogs throughout the camp whined and howled and were restless. The people in their lodges fell asleep. The man sang from sunset to midnight; then he began to wail. The people were all sleeping in their lodges and did not hear him. Again he sang; then he walked out to the opening of the camp circle, singing as he went. At the opening of the camp circle, he ceased singing and went out. All the dogs of the whole camp followed him, both male and female, some carrying in their mouths their puppies. Four times he sang before he reached his destination at daybreak. As the sun rose he and all the dogs arrived at a river bottom which was partly timbered and level.

The man sat down by a tree that leaned toward the north. Immediately the dogs ran from him and arranged themselves in the form of a semi-circle about him, like the shape of the camp-circle they had left; then they lay down to rest; as the dogs lay down, by some mysterious power, there sprang up over the man in the center of the circle a lodge. The lodge included the leaning tree by which the man sat; there were three other saplings, trimmed at the base with the boughs left at the top. The lodge was formed of the skins of the buffalo. As soon as the lodge appeared, all the dogs rushed towards it. As they entered the lodge they turned into human beings, dressed like members of the Dog-Men Society. The Dog Men began to sing, and the man listened very attentively and learned several songs from them, their ceremony, and their dancing forms.

The camp circle and the center lodge had the appearance of a real camp circle for three long days. The Dog Men blessed the man and promised that he should be successful in all of his undertakings and that his people, his society, and his band would become the greatest of all if he carried out their instructions.”

Later, the Cheyenne discovered the camp. But “as they came into view of the wonderful camp the Dog lodge instantly disappeared and the Dog-Men were transformed into dogs. The medicine men and warriors were by this time very sorry that they had refused to join this man’s society—and the next day, according to instructions of the Great Prophet, he again asked the warriors to join his society, and many hundreds of men joined it. He directed the society to imitate the Dog Man in dress and to sing the way the Dog-Men sang. This is why the other warrior societies call the warriors of this society ‘Dog-Men Warriors’.” So much for the fabulous origin of the organization.

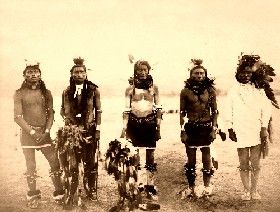

The uniform of the society consisted of a bonnet covered with upright feathers of birds of prey, a whistle suspended from a thong around the neck and made of the wing bone of an eagle, leggings, breechclout, and moccasins. The belt was made of four skunk skins. The Dog Soldiers carried a bow and arrows and a rattle shaped like a snake was used to accompany their songs. They had one chief and seven assistants, of whom four were leaders in battle, chosen on account of their extraordinary courage. These four wore, in addition to the usual uniform, a long sash which passed over the right shoulder and hung to the ground under the left arm, decorated with porcupine quills and eagle feathers. Of these four men, the two bravest had their leggings fringed with human hair.

The society has a secret ritual that occupies four days and has a series of four hundred songs used in its ceremonies and dances. It was often called upon to perform police duties in a large camp and enjoyed certain privileges in the tribe, such as the right to kill any fat dog whenever a feast was in order.

The powers of a warrior society in doing police duty were great, and their punishments severe against those who violated camp regulations. Not infrequently they whipped delinquents with quirts, beat them with clubs, or killed their ponies. For small offenses, they might cut up a man’s robe, break his lodge poles, or slash his tipi cover. They had charge of the tribal buffalo hunt and saw to it that the rules governing the hunt were observed and that all men had an equal chance to kill meat. They prevented any individual hunting until after the needs of the camp had been supplied.

About 1830 all the men of the Masiskota Cheyenne band and joined the Dog Soldiers The society was then comprised of about half the men in the tribe and was the most distinct, important, and aggressive of all the warrior societies of the Cheyenne.

Though much has been written regarding Cheyenne battles, probably the most authentic accounts are those given by George Bird Grinnell, in The Fighting Cheyennes, 1916, and all who discuss the exploits of the Dog Soldiers must necessarily be indebted to him. It must not be supposed that the following brief account attempts to cover the exploits of the members of this organization. I wish only to enumerate the principal engagements in which the Dog Soldiers figured as an organization.

By 1840 the Dog Soldiers were so nervous and influential that the Cheyenne chiefs left it to them to decide whether or not peace should be made with the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache, following the very disastrous drawn battle with these tribes in 1838. The peace then made by the Dog Soldiers has never been broken. The disastrous fight with. the Pawnee in 1852 was a great misfortune to the Cheyenne, and in the following year, those who had lost relatives brought presents to the Dog Soldiers, urging them to avenge the dead. Accordingly, the Dog Soldiers led a campaign against the Pawnee, but, finding them re-enforced by a number of Pottawatomie, equipped with firearms, were forced to withdraw.

The Dog Soldiers were thoroughly conservative and inclined to follow the advice of their tribal culture hero, who had warned the people that intercourse with white men would be to their disadvantage. Accordingly, in 1860, they refused to sign the treaty submitted by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs at Bent’s Fort on the upper Arkansas River, saying that they would never settle on a reservation. Members of the organization were active in raiding along the Platte River, following the disgraceful Sand Creek Massacre perpetrated by Colorado volunteers upon friendly and defenseless Indians.

In 1865 the Dog Soldiers were prominent factors in the combination of the Southern Cheyenne and Northern Cheyenne with the Ogallala Sioux, whose objective was the raiding of the emigrant road near the Platte bridge. There a stockade had been erected, known as Camp Dodge. It is estimated that this war party numbered three thousand men.

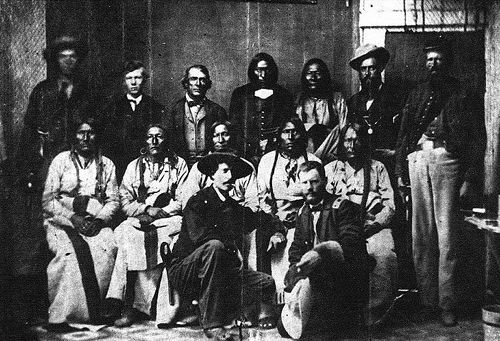

The Dog Soldiers assumed police duties during this expedition and succeeded in preventing the troops from discovering the presence of the Indians until decoys had lured them out of the fort. The success of Indian strategy on this occasion has been credited to their most famous leader, Roman Nose. In 1865 another attempt was made to hold a council and make a treaty with the Cheyenne, Arapahoe, Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache. The Commission met the tribes on the Arkansas River, and reservations were set aside in the region to the south. This treaty was accepted as binding by most of the Cheyenne, but the Dog Soldiers would have nothing to do with it, though two attempts were made to induce them to leave lands which they had never ceded to the government.

At this time the Dog Soldiers were friendly, but the tactlessness of General Winfield Hancock soon drove them to hostility. He apparently knew nothing of Indians and insisted upon dealing only with Roman Nose, who, though a very prominent warrior, was not a chief at all. When General Hancock attacked, the Cheyenne succeeded in getting away with their usual ease, leaving their village to be burned, and the only Indians killed were six friendly ones, who had come up to the Dog Soldiers’ camp on a visit. During four months of active campaigning, General Hancock, with a force of fourteen hundred men, consisting of cavalry, artillery, and infantry, succeeded in killing only two hostile Indians.

After the failure of General George Custer’s summer campaign on the Republican and Smoky Hill Rivers, the Cheyenne were induced to come in for the Medicine Lodge Treaty, but as Fort Reno, Fort Phil Kearny, and Fort Smith had been built along the Powder River road to Montana, through the last remaining hunting grounds of the tribe, the treaty came to nothing, for the Indians could not sit quietly by while their livelihood, the buffalo, was being destroyed.

The Beecher Island fight in 1868 has been much celebrated because of its spectacular features, and the prominence of the leaders on both sides. Here the Dog Soldiers formed the bulk of the Indian fighting force. Roman Nose, the most famous of the Northern Cheyenne, and a prominent Dog Soldier, led a charge and was killed by one of the scouts hidden in the grass. The story of his death as narrated to me by the late George Bent of Colony, Oklahoma, has elements of tragic interest. It seems that Roman Nose depended for protection upon his war bonnet and that the protective power of this war bonnet depended upon his observance of certain taboos. One of these was that he should never eat food that had been touched by an iron fork. Shortly before the battle, Roman Nose had eaten food served at a feast and had afterward learned that the food had been prepared with such a fork. He did not desire to enter the battle, believing that he would be killed because the protective power of his war bonnet had been destroyed. However, when he saw his warriors failing before the rifles of the white scouts, he mounted his horse and led the charge in which he fell. Of the six Cheyenne killed in this fight, five were Dog Soldiers.

After their defeat by the buffalo hunters at Adobe Walls, Texas in 1874 and the capture of the Southern Cheyenne village by Colonel R. S. McKenzie in 1875, White Horse, with the Dog Soldiers, came in and surrendered at Darlington, Oklahoma.

No doubt members of the Dog Soldiers’ Society were present at the Custer battle, and perhaps at the capture of Dull Knife’s village, but with this surrender at Darlington, the military life of the organization may be said to have come to an end.

However, there was trouble again when the government moved the Northern Cheyenne to the then Indian Territory in order to put the whole tribe on one reservation. The climate of Oklahoma did not agree with the Cheyenne from Montana. They died in large numbers. Medical supplies and rations were short, and within a year after their removal, the Northern Cheyenne were so dissatisfied that a number of them resolved to fight their way back to the north. The story of this wonderful retreat is well known and is worthy of a place beside that of philosopher Xenephon or that of the equally great retreat of Chief Joseph. Tangle Hair, head chief of the Dog Soldiers, was one of those who fled to the north, but the real leader of the expedition was Little Wolf. The Indians were successful in reaching their destination and remained there about a year before General Nelson Miles persuaded them to surrender.

Tangle Hair and a number of the Dog Soldiers had split off from the main party and followed Dull Knife. These Indians were imprisoned in Fort Robinson, and on their refusing to return to the south were starved by the officer in charge for eight days. At the end of that time, they broke from their prison and attempted to make their escape over the moonlit snow. In this fight more than a third of the Indians, men, women, and children, were killed, among them Tangle Hair, Chief of the Dog Soldiers. Before the outbreak, he had been told that he and his family might leave the prison, but he as well as the other Dog Soldiers refused to consider such a step. He was killed attempting to stand off the soldiers while the women and children made their escape.

This brief summary of the exploits of the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers will perhaps give some idea of the important part played by this organization in the many victories and hard-fought battles of the most warlike of the Plains tribes. Only a much more detailed narration could give any proper idea of the splendid courage—often in the face of overwhelming odds—displayed by members of this organization, times without number, in battle, whether against United States troops, Mexicans, or other Indian tribes. But this brief enumeration of the principal engagements of the Dog Soldiers may help to explain how it was that the United States government in its campaigns against the Cheyenne spent a million dollars and lost twenty-four lives for every Cheyenne killed.

W.S. Campbell, 1921. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2022.

This tale, written by W.S. Campbell appeared in the Chronicles of Oklahoma, Volume 1, No. 1, January 1921. The text as it appears here; however, is not verbatim as it has been edited for clarity and ease of the modern reader.

Also See:

Cheyenne – Warriors of the Great Plains

Dull Knife – Northern Cheyenne Chief

Little Wolf – Courageous Leader of the Cheyenne