By Catherine Clinton

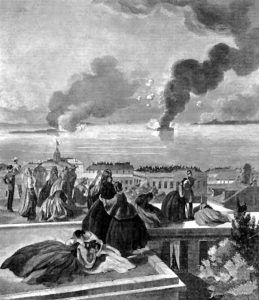

The coming of the Civil War was not unanticipated because the sectional conflict had been at the center of American politics for several decades before the firing on Fort Sumter, South Carolina, in April 1861. Yet, the war was a rude awakening for most Americans who had not realized that Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 and secession fever would culminate in an armed struggle for Confederate independence. Few imagined that this conflict would escalate into a full-scale bid to destroy slavery and result in waves of African Americans struggling openly for full and equal rights as citizens, many through the dangerous rite of passage as Union soldiers. Hardly anyone imagined that the conflict would result in the kind of total war that would absorb the entire nation for over four years and deprive the country and families of half a million young men.

This conflict became all-encompassing, touching the lives of nearly all Americans — slave and free, black and white, native-born and immigrant, property owner and wage earner, man and woman, adult and child — dramatically transformed by this momentous battle to decide the country’s future. Like many armed engagements, even its name reflected dispute. Lincoln and his government wished to minimize secession, hoping to ignore the sovereignty of the Confederacy. But certainly, the “War for the Union,” or the “Civil War,” was the most popular Yankee appellation. Ardent Confederates had other names: the “Second American Revolution, “the “War of Northern Aggression,” the “War for Southern Independence,” and the “War for States’ Rights.” Most Americans, horrified by how the nation was ripped apart, viewed it as “the Brother’s War.” Indeed, the conflict deeply divided hundreds of households and thousands of kinship networks when volunteers were needed.

Symbolic of this division was that four of Lincoln’s brothers-in-law wore Confederate uniforms. Despite Mary Todd Lincoln’s staunch devotion to the Union, her southern relations were loyal to the Confederacy. Other prominent politicians found themselves in difficult straits: Senator George B. Crittenden of Kentucky had two sons fighting in the war — one a major general for the Confederacy and the other a major general of the Union. Major Robert Anderson, in charge of federal troops at Fort Sumter, was the son-in-law of the governor of Georgia. Across the bay, he faced his artillery instructor at West Point, Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard, who fired on his star pupil and former assistant. Many West Point graduates, friends, and roommates faced one another on the battlefield and served alongside military school comrades. Friendship and kinship were rent asunder by the great onslaught of the Civil War.

Childhood was dramatically affected by the onset of war. The overwhelming youth of the armies on both sides and how young men flocked to battle had a generational impact on America. Out of 2,700,000 federal soldiers, over two million were 21 or younger, and over a million were younger than 18. Rough estimates are that 100,000 served in the Union army at 15 or younger, with 300 under 13 and 25 under the age of 10. Most of these extremely youthful volunteers were in the drum and fife corps, but their separation from families and exposure to deprivation and danger could be traumatizing.

Only 46,000 soldiers were over 25 in a sampling of a million federal enlistments. Youthful officers became a hallmark of the Union army, with Galusha Pennypacker rising to the rank of brevet major general at 17, too young to vote until the war ended. George Custer rose to this exalted rank at the age of 21 and joined six other Union generals in their twenties.

Confederates had equally legendary youths in military service. Brigadier General William P. Roberts of North Carolina rose to his rank at the age of 20. Boys in gray were equally common, and Confederate troops had disproportionate numbers of teenagers as well. Still, samplings of rebel ranks indicate more significant numbers of men in their twenties and thirties and a larger group of older soldiers, especially as the war wore on. In any case, families were stripped of manpower and the war depleted communities. One town in Wisconsin witnessed 111 of the 250 registered voters volunteering for the army. The farm boys of the midwestern states entered the Union ranks in droves.

However, no group was more electrified by the 1860 election than free blacks. Thomas Hamilton, the founder of the New York weekly newspaper, the Anglo-African, had warned in March 1860: “We have no hope from either [of the] political parties. We must rely on ourselves, the righteousness of our cause, and the advance of just sentiments among the great masses of the . . . people.” However, the majority of African Americans supported Lincoln. The Colored Republican Club of Brooklyn raised a “Lincoln Liberty Tree” in the summer of 1860, and similar signs of African American solidarity dotted the northeastern seaboard and Old Northwest riversides. Most eligible black voters cast their ballots for Lincoln.

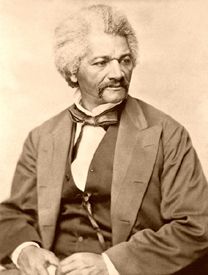

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery and escaped to spend his life fighting for justice and equality for all people.

Frederick Douglass crowed over Lincoln’s victory: “For fifty years the country has taken the law from the lips of an exacting, haughty and imperious slave oligarchy . . . . Lincoln’s election has vitiated their authority, and broken their power.” The threat of disunion buoyed black activists during post-election chaos. In the North, they rallied to the cry, “BREAK EVERY YOKE.” Blacks saw the split in the Union as a sign that the North could no longer tolerate slaveholders’ tyranny.

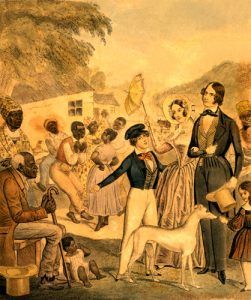

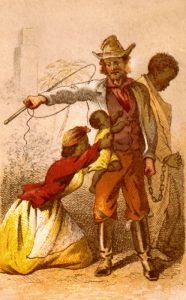

White Southerners interpreted Lincoln’s election and the response to secession in equally strong terms. Further, slaveholders feared the undermining of their authority, which armed federal intervention represented. The slave grapevine rattled with the threat of war. In the Deep South, conspiracies and plots spontaneously combusted in the war’s first few weeks. On May 14, 1861, a planter in Jefferson County, Mississippi, wrote to the governor concerning his fears: “A plot has been discovered, and already three Negroes have gone the way of all flesh or rather paid the penalty by the forfeiture of their lives.” He argued that 11,000 slaves surrounding less than a thousand whites might instigate a devastating insurrection. The plotters’ “diabolical” plans included killing white males, capturing white females, and marching “up the river to meet ‘Mr. Linkin’ bearing off booty such things as they could carry.” Planter paranoia prevailed in the Delta countryside.

By the end of the long, hot summer of 1861, a plot was uncovered in Adams County, Mississippi, when a woman reported “that a miserable, sneaking abolitionist has been at the bottom of this whole affair. I hope that he will be caught and burned alive.” Alarm ran rampant in the rural interior, where husbands and sons had been lured off to the Confederate army, and blacks routinely outnumbered whites 20 to one. Local investigators determined that this homegrown conspiracy was the work of slaves, planning to rise against masters in the event of a federal invasion. By mid-September, Home Guards and Vigilance Committees in Adams County were on the offensive and nearby counties on alert. Reportedly, 27 black men were hanged. A woman writing from her plantation confided, “It is kept very still, not to be in the papers.”

With the outbreak of war, the Confederacy required the utmost cooperation of all her citizens, especially the sons and daughters of the planter class. The newly formed government did not want hysteria in the countryside and slave owners arming themselves against their own slaves. As a result, evidence of insurrectionary activity was repressed. Despite the protracted efforts of Confederate loyalists to portray only harmony among owner and slaves, despite best efforts to rally blacks to the Stars and Bars, we know not all African Americans were devoted servants to Confederate masters, as painted by wartime rhetoric or postwar ideologies.

Equally interesting evidence remains, however, on this question of black loyalty. In New Orleans, Louisiana, Confederate leaders confronted an affluent, articulate, and assimilated free black community. The colored Creoles were in a difficult position when Louisiana left the Union — a people without a country. The mixed-race “mulatto” community emphasized community ties and volunteered to “take arms at a moment’s notice and fight shoulder to shoulder with other citizens.” A local unit of “colored men” even enrolled in the state militia.

However, African American men who formed companies and offered themselves for military service were greeted with considerable discomfort by the new southern government, ignored, and spurned. The Confederacy dared not allow blacks to serve as soldiers. Free blacks who volunteered were assigned to projects as teamsters on earthworks projects, building fortifications, and other menial support roles. The loyalties of these free black volunteers were considerably divided. Like the New Orleans Native Guards, most feared that if Confederate independence was achieved without their help, they might be returned to slavery. To safeguard their status, they pledged themselves to the Confederate cause — perhaps even aware of the emptiness of such a gesture.

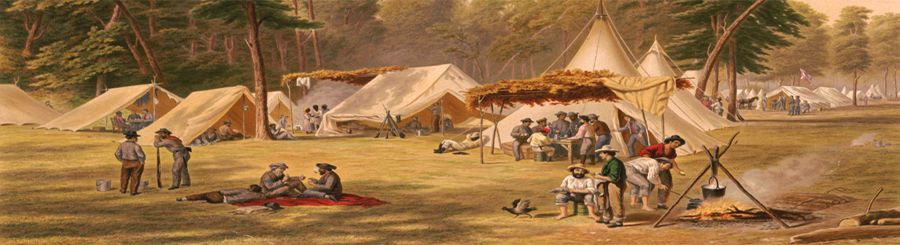

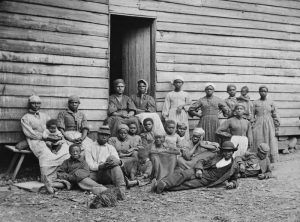

From the very earliest days of the war, slaves were caught in a vicious thrall. Many hoped to escape bondage and fled behind enemy lines. The flooding of Union camps with fugitive slaves was an alarming and unanticipated development for federal officers. Confederates who claimed that slaves were loyal to owners because the system of paternalism fostered mutual dependency were repudiated by a steady stream of black desertions. Unfortunately, federal soldiers expressed less than sympathetic attitudes toward blacks in bondage, such as the Union man who balked at the suggestion that he was fighting for blacks’ freedom and retorted: “I ain’t fighting for the damned ni**ers, I’m fighting for fifteen dollars a month.”

Despite such rampant racism among federal troops, African Americans overwhelmingly sided with the Union — indeed, the Native Guards proved their true colors during a federal occupation. When Union forces threatened to overrun New Orleans in the spring of 1862, black troops volunteered to remain behind. They ended up greeting soldiers in blue with jubilation and switching sides effortlessly.

From the earliest days of the war, federal military units employing blacks were organized in South Carolina and Louisiana to capture the runaways and harness their loyalty. Thousands of African Americans were willing to take up arms against the Confederacy. The flood of black volunteers northward from the Confederate states increased dramatically with the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863. It was a time of tremendous rejoicing for slaves trapped behind Confederate lines. Most thought of New Year’s Day with sadness, as it was the time when sales were organized and families separated, nicknamed “Heartbreak Day.” But after 1863, most African Americans would celebrate instead of dreading this date.

The Union initially resisted using blacks as soldiers, although these runaways, who were called contraband, were welcomed and employed as teamsters and ditch diggers to man the engineering and quartermasters’ corps. But free blacks persisted, and commanders relented, so well over 100,000 black men from Confederate states ran away to join the Union army. By the war’s end, nearly 200,000 African Americans had served under the Union flag.

Despite Confederate efforts to stem the tide, the Federals could drain plantations of precious manpower and, even more boldly, allow former slaves to return to these plantations as enemy soldiers — an alarming prospect for most planter households. As one former slave soldier reported, when he went to see his mistress after the Battle of Nashville, she upbraided him, reminding him of how she nursed him when he was sick, and “‘Now, you are fighting me!’ I said, ‘No’m, I ain’t fighting you, I’m fighting to get free.'”

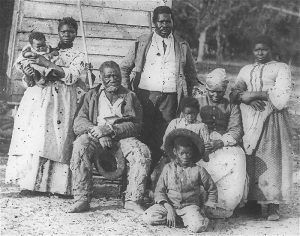

Slave women and families left behind by fathers and husbands could be thrown into precarious situations when planters discovered “treason” and vented their anger on family members who remained in slavery. One wife left behind in Missouri confided: “They are treating me worse and worse every day. Our child cries for you. Send me some money as soon as you can, for my child and I are almost naked.” A white commander of a black regiment complained that planters forbade wives and children to see these black men in blue and prevented all communication, especially the flow of wages back to the plantation home. Some African American soldiers, driven to desperation by such treatment, risked all to return and retrieve families, such as Spottswood Rice, who plotted from his hospital bed to rescue his children: “Be assured that I will have you if it cost me my life.” One Kentucky woman spirited her several children away, only to be halted on the road by her master’s son-in-law, “who told me that if I did not go back with him, he would shoot me. He drew a pistol on me as he made this threat. I could offer no resistance as he constantly kept the pistol pointed at me.” Forcing her to return to slavery at gunpoint, the man kept her seven-year-old hostage to ensure that she wouldn’t run away again.

Black women of the South, like white women, suffered when menfolk went off to war. Jane Welcome wrote a letter complaining to Lincoln: “I wont to know sir if you please wether I can have my son relest from the arme he is all the support I have now his father is dead, and his brother was all the help that I had.” The president’s office replied: “The interests of the service will not permit that your request be granted.” But evidence also suggests that many black women willingly bade slave men off to war. Although fearing for soldiers’ safety and dreading repercussions, they saw this occasion as a golden opportunity to secure future freedom. Only 11 percent of the black population within the country was free, and most slaves knew military service as a means of liberation. The masses of African Americans who joined the Union undermined the Confederate cause and strengthened the fight for emancipation. Blacks in the Union armed forces struck a vital blow to white southern pride, all the while crippling the plantation economy. In the North, the persistence of the free black community prodded the federal government into accepting black military potential.

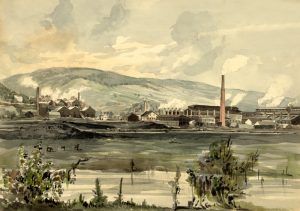

When the war broke out in 1861, the North believed in moral superiority and material advantage. The Union was a powerful image, and Lincoln used his “house” metaphor, hoping to keep the national family together. The Union wanted to impress upon its sibling rival that it possessed more improved farmland than the South and more soldiers in its growing population than the Confederacy. Southern superiority in exports, almost exclusively cotton, could be abolished with the blockade. The North had over 125,000 industrial firms, and the South had less than 20,000. New York State alone manufactured four times the value of manufactured products as the Confederacy did. One county in Connecticut manufactured more firearms than all the southern states combined.

The North had more and better ports, superior canals, and generally better transportation. Although the United States boasted one of the largest railroad networks in the world, less than one-third of its tracks were in the southern states — and 96% of American trains were manufactured in the North. Southern shipbuilding was considerably inferior to the size and scope of Northern naval capabilities. Financial centers, especially sophisticated trade in bonds, were concentrated along the northeastern seaboard. Southern farmers were less commercially acclimated than the New England, Middle Atlantic, and Old Northwest homesteaders fed by flatboat and steamer trade, with closer ties to eastern markets.

At the same time, most white southern volunteers had been trained in local militias and were better equipped to forage from their hunting expertise. Further, the Confederacy declared its independence, which meant it could conduct a defensive war against Yankee invaders, a far more straightforward tactic than the conquest required for Union victory. The numbers were reputedly against Confederate victory, but the spirit was strong, and the North had not anticipated just how entrenched and determined Confederate rebels had become.

From the National Park Civil War Series, Life in Civil War America, Catherine Clinton, published by Eastern National 2008. Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See:

Slavery – Cause and Catalyst of the Civil War

Source: National Park Service E-Library